【2020-07-22】

贡布里希的这段话(《艺术的故事》第8章)让我想了很多:

现代艺术家那么追求创新,是被市场逼的,和如今的创业公司挖空心思力求成为独角兽,原理是一样的,因为规模经济和网络效应造成了一种只有独角兽才能生存的局面,对艺术来说,背后起作用的是传播和消费方式:并不是消费者真的需要那么多完全不同的新作品,而是因为只有全然不同的新作品才能让新进的艺术家有饭吃。

以音乐为例,且让我从一个极端的假设讲起,即便我们假设,消费者对是否有新作品丝毫不介意,而完全满足于数十(more...)

【2020-07-22】

贡布里希的这段话(《艺术的故事》第8章)让我想了很多:

现代艺术家那么追求创新,是被市场逼的,和如今的创业公司挖空心思力求成为独角兽,原理是一样的,因为规模经济和网络效应造成了一种只有独角兽才能生存的局面,对艺术来说,背后起作用的是传播和消费方式:并不是消费者真的需要那么多完全不同的新作品,而是因为只有全然不同的新作品才能让新进的艺术家有饭吃。

以音乐为例,且让我从一个极端的假设讲起,即便我们假设,消费者对是否有新作品丝毫不介意,而完全满足于数十(more...)

现代艺术家那么追求创新,是被市场逼的,和如今的创业公司挖空心思力求成为独角兽,原理是一样的,因为规模经济和网络效应造成了一种只有独角兽才能生存的局面,对艺术来说,背后起作用的是传播和消费方式:并不是消费者真的需要那么多完全不同的新作品,而是因为只有全然不同的新作品才能让新进的艺术家有饭吃。

以音乐为例,且让我从一个极端的假设讲起,即便我们假设,消费者对是否有新作品丝毫不介意,而完全满足于数十年如一日翻来覆去听(比如10首)老曲子,同时他们也不介意时不时可能有一首新曲子,只要它好听就行,我想说的是,即便这种看起来最不鼓励创新的条件下,现代艺术市场也会远比古代市场更鼓励创新。

在古代,哪怕一千年没有新曲子,要满足100万人每人每年听几次的需求,也需要大批音乐家,因为每次表演只能同时服务于几十最多上百人,于是,一个完全没有创新的音乐产业,也可以让众多音乐家生存,具体养活多少,取决于表演次/欣赏次之间的比例关系。

可是技术进步会改变这一比例,考虑另一个极端:假如所有人都在spotify上听歌,而且全都满足于相同的10首歌来回放,那么,等这些歌的作者死光之后,音乐市场就再也不需要新的音乐家了,可是有志于靠音乐吃饭的人不甘心啊,所以他们必须写新曲子,努力说服至少一部分听众把他们的新歌加入播放列表。

这两个极端之间,一些早先的技术进步也可能改变上述比例关系,比如:扩音器,具有专业音响效果的音乐厅,精确的乐谱记录和复现手段(包括指挥),铁路飞机扩大了音乐家服务半径,等等。

除了音乐,类似的机制或许在其他艺术形式中也存在,不过我还没想清楚。

现代艺术家那么追求创新,是被市场逼的,和如今的创业公司挖空心思力求成为独角兽,原理是一样的,因为规模经济和网络效应造成了一种只有独角兽才能生存的局面,对艺术来说,背后起作用的是传播和消费方式:并不是消费者真的需要那么多完全不同的新作品,而是因为只有全然不同的新作品才能让新进的艺术家有饭吃。

以音乐为例,且让我从一个极端的假设讲起,即便我们假设,消费者对是否有新作品丝毫不介意,而完全满足于数十年如一日翻来覆去听(比如10首)老曲子,同时他们也不介意时不时可能有一首新曲子,只要它好听就行,我想说的是,即便这种看起来最不鼓励创新的条件下,现代艺术市场也会远比古代市场更鼓励创新。

在古代,哪怕一千年没有新曲子,要满足100万人每人每年听几次的需求,也需要大批音乐家,因为每次表演只能同时服务于几十最多上百人,于是,一个完全没有创新的音乐产业,也可以让众多音乐家生存,具体养活多少,取决于表演次/欣赏次之间的比例关系。

可是技术进步会改变这一比例,考虑另一个极端:假如所有人都在spotify上听歌,而且全都满足于相同的10首歌来回放,那么,等这些歌的作者死光之后,音乐市场就再也不需要新的音乐家了,可是有志于靠音乐吃饭的人不甘心啊,所以他们必须写新曲子,努力说服至少一部分听众把他们的新歌加入播放列表。

这两个极端之间,一些早先的技术进步也可能改变上述比例关系,比如:扩音器,具有专业音响效果的音乐厅,精确的乐谱记录和复现手段(包括指挥),铁路飞机扩大了音乐家服务半径,等等。

除了音乐,类似的机制或许在其他艺术形式中也存在,不过我还没想清楚。

【2019-06-06】

John Hancock公司的这个寿险产品是我见过最好的健康生活方式督促器,可是有人就不高兴了,说嘎呋闷特该管管了,同是这批人,若是换作没啥鸟用的可乐税或餐桌盐瓶禁止令,大概会拍手叫好,好笑的是,这个博客的名字叫ProMarket,Pro你个头

On September 19, 2018, John Hancock, one of the oldest life insurance companies in the US, made a radical change: it (more...)

On September 19, 2018, John Hancock, one of the oldest life insurance companies in the US, made a radical change: it stopped offering life insurance priced by traditional demographics like age, health history, gender, and employment history.

Instead, John Hancock began offering coverage priced according to interactions with policyholders through wearable health devices, smartphone apps, and websites. According to the company, these interactive policies track activity levels, diet, and behaviors like smoking and excessive drinking. Policyholders that engage in healthy behaviors like exercise or prove that they have purchased healthy food receive discounts on their life insurance premiums, gift cards to major retailers, and other perks; those who do not presumably get higher rates and no rewards. According to John Hancock these incentives, along with daily tracking, will encourage policyholders to live longer and have lower hospitalization-related costs.

保险商信息获取和风险甄别的革命性提升,无疑会深刻改变保险业态,但说那会摧毁保险业的存在基础,就有点杞人忧天了,常见的一种担忧是,假如保险商都抢着刮蛋糕上的奶油,剩下的劣质客户的保费就会高到没销路的程度,可问题是,要刮掉多少奶油才会出现这种局面?保险商若是全知上帝,保险业就不复存在,这大概没错,但他们远非全知,他们采集信息的能力确实在迅速提高,但消费者的一种可能反应是提前买,在风险相关信息变得可采集之前就买,有何理由认为这种需求不会有供应商来满足呢? 还有一种可能性,被刮剩下的蛋糕渣或许单独无法成为有价值的保险开发对象,但仍可能和其他产品组合起来而变得市场可行,比如抽烟喝酒胡吃海喝的没人愿意保,可是早死也有早死的好处啊,和年金结合起来就是个办法,若是再放弃几种续命治疗,好像还挺有吸引力的吧。【2018-10-21】

https://voxeu.org/article/top-firms-and-decline-local-product-market-concentration

随着排名前几位的大型连锁零售商规模扩张,市场份额提高,零售市场的集中度当然也提高了,但这里提高的是全局市场的集中度,而该指标对于个体消费者是没意义的,消费者真正关心的是他自己的有效购物半径内有多少选择,因而对他们有意义的指标是各局部市场的集中度,研究发现,大型连锁厂商的扩张非但没有提高反而降低了局部市场的集中度

原理其实不难理解,因为结构高度扁平化的大型连锁企业,其每家门店的管理成本远远低于独立企业,因而只须在每个局部市场分到一小块即可实现盈亏平衡,而独立企业(more...)

【2018-09-05】

看眼下大公司政治站队这么积极的势头,突然冒出一个念头:未来各类消费品市场会不会出现几大品牌分别对应不同党派的局面?雇佣市场的党派分化或许来的更快?

从左派对待NRA合作商的劲头看,他们总有一天也会发动对FoxNews广告客户的抵制行动,然后许多公司被迫站队……若这种情况升级到某个程度,就会引发连锁反应,因为被腾出的市场空间总会吸引其他厂商来占领,沃尔玛和麦当劳估计会选择右边……

(more...)和保健品厂商一样,记者们总是热衷于使用一些偶尔从专家嘴里听来,自己却不太弄得明白的高深术语,诸如博弈,囚徒困境,自私基因,悖论,伪命题……,在众多此类术语中,『市场失灵』是颇受欢迎的一个,大概是因为它有着恰到好处的似懂非懂性——既显得足够高深,又不至于完全不知所云,很适合为进一步的社会批评、政策呼吁,乃至道义铁肩的展示做铺垫。

那么,当人们说市场失灵时,所要表达的究竟是什么呢?在经济学家那里,市场失灵(market failure)是指一组特定的经济现象,它们大多在本书各章中得到了讨论,包括:因所有权缺失而导致的公地悲剧,因搭便车问题而造成的公共品供给不足(第1、2章),外部性带来的无效率(第3章),因资产特化和网络效应而造成的低水平均衡(或者叫路径锁入,第4、5、6章),因单方面资产特化而造成的合约套牢(第7、8章),因信息不对称造成的柠檬市场或委托代理无效(第9章),因掠夺性定价、网络效应或先行优势而造成的自然垄断(第10、11、12章),由非理性行为导致的价格泡沫(第13章)。

何以将这些十分不同的现象归为一类?理由并不明确,常见的说法是,它们都偏离了帕累托最优,即存在帕累托优化的余地,但实际上,其中大部分跟帕累托最优无关,比如旨在消除外部性的庇古税,被征税者的福利显然减损了,所以即便我们接受基数效用论,也充其量只能在理论上实现庇古优化,而非帕累托优化,类似的,即便我们相信某种外力能够将市场从低水平均衡中拉出,或避免合约套牢,或打破自然垄断,结果也只是改进了消费者和部分生产者的福利,而低水平均衡中的特化资产持有者、合约套牢中的讹诈者、自然垄断厂商的利益,无疑都减损了,因而这些改变都不是帕累托优化。

此外,正如各章作者所指出,经济学家基于这些现象所构造的模型在理论上是否成立,它们在现实世界中有多普遍,其影响有多重要,都是相当可疑的,而那些长久以来被视为这组模型之经典案例,被广为援引和传播的故事,则多半只是信口捏造或以讹传讹,对此,本书各章已有详尽论述。

不过,无论理论地位是否脆弱,现实重要性多么可疑,当经济学家说市场失灵时,他们的意思至少是明确的,相比之下,在非专业场合,这个词的用法就变得极为狂野,我在这里打算重点讨论的,正是这一状况;还是让我从语言分析开始吧。

假如我们发现某人未能完成某项视觉任务,并说:“视觉系统失灵”——这究竟是什么意思呢?实际上,这句话的语义太含混了,有太多种可能的解读:

1)此人的(原本好好的)视觉系统此时此刻失灵了。或许是某种疾病(比如视网膜动脉栓塞)发作让他暂时失明;

2)此人的视觉系统向来不灵。或许他是个盲人,或者色盲,或者深度近视,等等;

3)人类的视觉系统不灵。双眼布局造成的视野局限让人类无法(像毛驴那样)完成要求视野角度超过180度的任务,分辨率局限也让我们无法像老鹰那样看清那么远的东西;

4)脊椎动物的视觉不灵。脊椎动物视觉系统的结构缺陷造成的盲点,让我们无法完成某些特殊的视觉任务;

5)

【2016-07-22】

不少朋友对金融/投资界的人为何也那么反市场感到困惑不解,among others, 一个明显的理由是退休基金的市场份额在过去几十年中大幅膨胀,这些基金的管理者大多喜欢迎合流行风潮,为了表现自己的政治正确,他们往往表现的比一般白左还要过火,至于内心是否真的相信那一套,则是另一码事。

Entrepreneurship and American education

创业活动与美国教育

作者:Michael Q. McShane @ 2016-05-10

译者:Tankman

校对:混乱阈值(@混乱阈值)

来源:AEI,http://www.aei.org/publication/entrepreneurship-and-american-education/

Key Points

要点

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

A Case against Child Labor Prohibitions

对禁用童工的一个反对意见

作者:Benjamin Powell @ 2014-07-29

译者:Eartha(@王小贰_Eartha)

校对:辉格(@whigzhou)

来源:Cato Institute,http://www.cato.org/publications/economic-development-bulletin/case-against-child-labor-prohibitions

Halima is an 11-year-old girl who clips loose threads off of Hanes underwear in a Bangladeshi factory.1 She works about eight hours a day, six days per week. She has to process 150 pairs of underwear an hour. At work she feels “very tired and exhausted,” and sometimes falls asleep standing up. She makes 53 cents a day for her efforts. Make no mistake, it is a rough life.

哈丽玛是个十一岁的小女孩,在孟加拉的工厂里给Hanes牌内衣修线头,每天工作八小时,每周六天。① 她每小时需要处理150套内衣,工作时觉得“非常劳累”,有时站着就睡着了。而这样的努力工作每天能换来53美分。毫无疑问,这种生活非常艰苦。

Any decent person’s heart would go out to Halima and other child employees like her. Unfortunately, all too often, people’s emotional reaction lead them to advocate policies that will harm the very children they intend to help. Provisions against child labor are part of the International Labor Organization’s core labor standards. Anti-sweatshop groups almost universally condemn child labor and call for laws prohibiting child employment or boycotting products made with child labor.

任何一个正派人的内心都会对像哈丽玛这样的童工充满同情。但遗憾的是,人们的情绪化反应常常指引他们支持错误的政策,这反而会伤害那些他们原本想帮助的孩子。禁用童工条款是国际劳工组织的核心劳工标准的一部分。反对血汗工厂的团体几乎一致谴责使用童工的行为,呼吁通过禁止雇佣童工的法律或是抵制使用童工生产的商品。

In my recent book, Out of Poverty: Sweatshops in the Global Economy, I argue that much of what the anti-sweatshop movement agitates for would harm workers and that the process of economic development, in which sweatshops play an important role, is the best way to raise wages and improve working conditions. Child labor, although the most emotionally charged aspect of sweatshops, is not an exception to this analysis.

在我的新书《走出贫困:全球经济中的血汗工厂》中,我认为反血汗工厂运动的许多诉求将会损害工人们的利益,经济发展才是提高工资与改善工作环境的最好办法,而血汗工厂在其中发挥着重要作用。虽然在情感上,雇佣童工是血汗工厂最受世人谴责的方面,但它在上述分析中也不例外。

We should desire to see an end to child labor, but it has to come through a process that generates better opportunities for the children—not from legislative mandates that prevent children and their familie(more...)

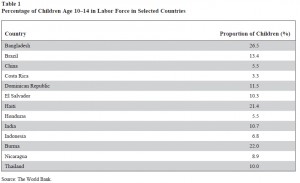

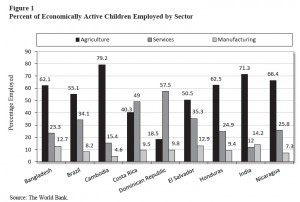

The World Bank also collects data on the economic sectors in which children are employed. Figure 1 presents the distribution of employment of economically active children between the ages of 7 and 14 by sector.6

世界银行也从雇佣童工的各个经济部门收集数据。表一依照经济部门展示了7-14岁年龄段中参与经济活动的儿童在各行业中的分布情况。⑥

The World Bank also collects data on the economic sectors in which children are employed. Figure 1 presents the distribution of employment of economically active children between the ages of 7 and 14 by sector.6

世界银行也从雇佣童工的各个经济部门收集数据。表一依照经济部门展示了7-14岁年龄段中参与经济活动的儿童在各行业中的分布情况。⑥

In seven of the nine countries for which data exists, most children were employed in agriculture, often by a wide margin.7 In the two exceptions, Costa Rica and the Dominican Republic, the leading sector employing children was service. India had the highest proportion of children employed in manufacturing, and there it was a little over 14 percent.

有数据可查的九个国家中,七个国家的大部分儿童受雇于农业部门,远超其他行业。⑦ 哥斯达黎加与多米尼加共和国是两个例外,雇佣童工最多的是服务业。印度制造业雇佣童工的比例在各国中最高,略超过14%。

Protests against sweatshops that use child labor implicitly assume that ending child labor in sweatshops by taking away the option to work in a factory will, on net, reduce child labor. Evidence on child labor in countries that have sweatshops indicates that is wrong. It is not a few “bad apple” firms exploiting children in factories. Child labor is common. Employment in agriculture is not necessarily safer, either. A 1997 child labor survey showed that 12 percent of children working in agriculture reported injuries, compared with 9 percent of those who worked in manufacturing.8

对雇佣童工的血汗工厂进行抗议,这种行为暗含了一种预设,即通过除去儿童在工厂工作的选择从而终结血汗工厂里的童工现象,童工数量就会出现净减少。从拥有血汗工厂的国家所获取的证据显示,这是错的。真相并不是个别“害群之马”在工厂里剥削儿童。雇佣童工的现象是普遍的。而且,在农地里工作也并不必然更加安全。一份1997年的童工调查显示,农业部门有12%的童工曾遭伤害,制造业则是9%。⑧

Child Labor and Economic Development

童工与经济发展

The thought of Third World children toiling in factories to produce garments for us in the developed world to wear is appalling, at least in part because child labor is virtually nonexistent in the United States and the rest of the more developed world.9 Virtually nowhere in the developed world do kids toil long hours every week in a factory in a manner that prevents them from obtaining schooling.

第三世界的儿童们在工厂里辛苦劳动,为我们这些发达地区的人生产服装——这种念头让人惊骇,至少部分原因在于童工事实上并不存在于美国及其他发达地区。⑨ 事实上,没有发达国家会允许儿童们每周长时间地在工厂里辛苦工作,以至于无法接受学校教育。

Children typically worked throughout human history, either long hours in agriculture or in factories once the industrial revolution emerged. The question is, why don’t kids work today? Rich countries do have laws against child labor, but so do many poor countries. In Costa Rica the legal working age is 15, but an ILO survey found 43 percent of working children were under the legal age.10

纵观人类历史,儿童其实一直都在工作,不管是长时间在农地里劳作,还是工业革命之后进入工厂工作。真正该问的问题是:为何今天儿童不工作了?富裕国家确实有禁止童工的法律,但是很多贫穷的国家也有。哥斯达黎加的法定工作年龄是15岁,但是国际劳工组织的一项调查发现有43%的童工低于法定年龄。⑩

Similarly, in the United States, Massachusetts passed the first restriction on child labor in 1842. However, that law and other states’ laws affected child labor nationally very little.11 By one estimate, more than 25 percent of males between the ages of 10 and 15 participated in the labor force in 1900.12 Another study of both boys and girls in that age group estimated that more than 18 percent of them were employed in 1900.13 Economist Carolyn Moehling also found little evidence that minimum-age laws for manufacturing implemented between 1880 and 1910 contributed to the decline in child labor.14

同样,在美国,马萨诸塞州在1842年最先对童工加以限制。然而,那部法律连同其他州的法律对于全国范围内的童工情况影响甚微。⑾ 有人估算过,1900年10-15岁的男性中超过25%的人参与工作.⑿ 另一项研究将同年龄段的女性也纳入了估算范围,结果发现1900年有超过18%的儿童参与了工作。⒀ 经济学家卡洛琳·莫和林也找不到证据证明1880至1910年间针对制造业实施的最低工资法起到了减少童工的作用。⒁

Similarly, economists Claudia Goldin and Larry Katz examined the period between 1910 and 1939 and found that child labor laws and compulsory school-attendance laws could explain at most 5 percent of the increase in high school enrollment.15 The United States did not enact a national law limiting child labor until the Fair Labor Standards Act was passed in 1938. By that time, the U.S. average per capita income was more than $10,200 (in 2010 dollars).

经济学家克劳迪亚·戈尔丁与拉里·卡茨仔细调查了1910至1939年间的情况,发现童工相关的法律与强制入学的法律最多只能解释5%的高中入学率增长幅度。⒂ 直到1938年《公平劳动标准法》通过,美国才有了全国性的限制童工的法律。在那时,美国人均收入已超过10,200美元(以2010年美元计算)。

Furthermore, child labor was defined much more narrowly when today’s wealthy countries first prohibited it. Massachusetts’s law limited children who were under 12 years old to no more than 10 hours of work per day. Belgium (1886) and France (1847) prohibited only children under the age of 12 from working. Germany (1891) set the minimum working age at 13.16

此外,如今的富裕国家当年第一次出台法律禁止童工时,其定义要比现在狭窄的多。马萨诸塞州法禁止12岁以下儿童每天工作超过10小时。比利时(1886年)与法国(1847年)只禁止12岁以下儿童工作。德国(1891年)将最低工作年龄限定在13岁。⒃

England, which passed its first enforceable child labor law in 1833, merely set the minimum age for textile work at nine years old. When these countries were developing, they simply did not put in place the type of restrictions on child labor that activists demand for Third World countries today. Binding legal restrictions came only after child labor had mostly disappeared.

英格兰在1833年通过了第一部童工法,将纺织业的最低工作年龄仅仅设在9岁。当这些国家处于发展阶段,他们通过的限制标准可比不上今天这些活动家对第三世界国家所要求的。有效的法律约束只有在童工几近消失之后才会到来。

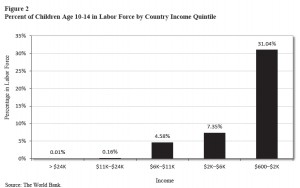

The main reason children do not work in wealthy countries is precisely because they are wealthy. The relationship between child labor and income is striking. Using the same World Bank data on child labor participation rates we can observe how child labor varies with per capita income. Figure 2 divides countries into five groups based on their level of per capita income adjusted for purchasing power parity. In the richest two fifths of countries, all of whose incomes exceed $12,000 in 2010 dollars, child labor is virtually nonexistent.

富裕国家的儿童不工作的主要原因就是他们比较富有。童工比例与收入之间的相关性是显著的。通过前文提到的世界银行关于童工比例的数据,我们可以观察到童工比例是如何随人均收入的变化而改变的。经购买力平价调整后,图2按照人均收入水平将各国分成五组。最富有的两组国家人均收入超过12,000美元(以2010年美元计算),童工几乎不存在。

In seven of the nine countries for which data exists, most children were employed in agriculture, often by a wide margin.7 In the two exceptions, Costa Rica and the Dominican Republic, the leading sector employing children was service. India had the highest proportion of children employed in manufacturing, and there it was a little over 14 percent.

有数据可查的九个国家中,七个国家的大部分儿童受雇于农业部门,远超其他行业。⑦ 哥斯达黎加与多米尼加共和国是两个例外,雇佣童工最多的是服务业。印度制造业雇佣童工的比例在各国中最高,略超过14%。

Protests against sweatshops that use child labor implicitly assume that ending child labor in sweatshops by taking away the option to work in a factory will, on net, reduce child labor. Evidence on child labor in countries that have sweatshops indicates that is wrong. It is not a few “bad apple” firms exploiting children in factories. Child labor is common. Employment in agriculture is not necessarily safer, either. A 1997 child labor survey showed that 12 percent of children working in agriculture reported injuries, compared with 9 percent of those who worked in manufacturing.8

对雇佣童工的血汗工厂进行抗议,这种行为暗含了一种预设,即通过除去儿童在工厂工作的选择从而终结血汗工厂里的童工现象,童工数量就会出现净减少。从拥有血汗工厂的国家所获取的证据显示,这是错的。真相并不是个别“害群之马”在工厂里剥削儿童。雇佣童工的现象是普遍的。而且,在农地里工作也并不必然更加安全。一份1997年的童工调查显示,农业部门有12%的童工曾遭伤害,制造业则是9%。⑧

Child Labor and Economic Development

童工与经济发展

The thought of Third World children toiling in factories to produce garments for us in the developed world to wear is appalling, at least in part because child labor is virtually nonexistent in the United States and the rest of the more developed world.9 Virtually nowhere in the developed world do kids toil long hours every week in a factory in a manner that prevents them from obtaining schooling.

第三世界的儿童们在工厂里辛苦劳动,为我们这些发达地区的人生产服装——这种念头让人惊骇,至少部分原因在于童工事实上并不存在于美国及其他发达地区。⑨ 事实上,没有发达国家会允许儿童们每周长时间地在工厂里辛苦工作,以至于无法接受学校教育。

Children typically worked throughout human history, either long hours in agriculture or in factories once the industrial revolution emerged. The question is, why don’t kids work today? Rich countries do have laws against child labor, but so do many poor countries. In Costa Rica the legal working age is 15, but an ILO survey found 43 percent of working children were under the legal age.10

纵观人类历史,儿童其实一直都在工作,不管是长时间在农地里劳作,还是工业革命之后进入工厂工作。真正该问的问题是:为何今天儿童不工作了?富裕国家确实有禁止童工的法律,但是很多贫穷的国家也有。哥斯达黎加的法定工作年龄是15岁,但是国际劳工组织的一项调查发现有43%的童工低于法定年龄。⑩

Similarly, in the United States, Massachusetts passed the first restriction on child labor in 1842. However, that law and other states’ laws affected child labor nationally very little.11 By one estimate, more than 25 percent of males between the ages of 10 and 15 participated in the labor force in 1900.12 Another study of both boys and girls in that age group estimated that more than 18 percent of them were employed in 1900.13 Economist Carolyn Moehling also found little evidence that minimum-age laws for manufacturing implemented between 1880 and 1910 contributed to the decline in child labor.14

同样,在美国,马萨诸塞州在1842年最先对童工加以限制。然而,那部法律连同其他州的法律对于全国范围内的童工情况影响甚微。⑾ 有人估算过,1900年10-15岁的男性中超过25%的人参与工作.⑿ 另一项研究将同年龄段的女性也纳入了估算范围,结果发现1900年有超过18%的儿童参与了工作。⒀ 经济学家卡洛琳·莫和林也找不到证据证明1880至1910年间针对制造业实施的最低工资法起到了减少童工的作用。⒁

Similarly, economists Claudia Goldin and Larry Katz examined the period between 1910 and 1939 and found that child labor laws and compulsory school-attendance laws could explain at most 5 percent of the increase in high school enrollment.15 The United States did not enact a national law limiting child labor until the Fair Labor Standards Act was passed in 1938. By that time, the U.S. average per capita income was more than $10,200 (in 2010 dollars).

经济学家克劳迪亚·戈尔丁与拉里·卡茨仔细调查了1910至1939年间的情况,发现童工相关的法律与强制入学的法律最多只能解释5%的高中入学率增长幅度。⒂ 直到1938年《公平劳动标准法》通过,美国才有了全国性的限制童工的法律。在那时,美国人均收入已超过10,200美元(以2010年美元计算)。

Furthermore, child labor was defined much more narrowly when today’s wealthy countries first prohibited it. Massachusetts’s law limited children who were under 12 years old to no more than 10 hours of work per day. Belgium (1886) and France (1847) prohibited only children under the age of 12 from working. Germany (1891) set the minimum working age at 13.16

此外,如今的富裕国家当年第一次出台法律禁止童工时,其定义要比现在狭窄的多。马萨诸塞州法禁止12岁以下儿童每天工作超过10小时。比利时(1886年)与法国(1847年)只禁止12岁以下儿童工作。德国(1891年)将最低工作年龄限定在13岁。⒃

England, which passed its first enforceable child labor law in 1833, merely set the minimum age for textile work at nine years old. When these countries were developing, they simply did not put in place the type of restrictions on child labor that activists demand for Third World countries today. Binding legal restrictions came only after child labor had mostly disappeared.

英格兰在1833年通过了第一部童工法,将纺织业的最低工作年龄仅仅设在9岁。当这些国家处于发展阶段,他们通过的限制标准可比不上今天这些活动家对第三世界国家所要求的。有效的法律约束只有在童工几近消失之后才会到来。

The main reason children do not work in wealthy countries is precisely because they are wealthy. The relationship between child labor and income is striking. Using the same World Bank data on child labor participation rates we can observe how child labor varies with per capita income. Figure 2 divides countries into five groups based on their level of per capita income adjusted for purchasing power parity. In the richest two fifths of countries, all of whose incomes exceed $12,000 in 2010 dollars, child labor is virtually nonexistent.

富裕国家的儿童不工作的主要原因就是他们比较富有。童工比例与收入之间的相关性是显著的。通过前文提到的世界银行关于童工比例的数据,我们可以观察到童工比例是如何随人均收入的变化而改变的。经购买力平价调整后,图2按照人均收入水平将各国分成五组。最富有的两组国家人均收入超过12,000美元(以2010年美元计算),童工几乎不存在。

It is only when countries have an income less than $11,000 per year that we start to observe children in the labor force. But even here, rates of child labor remain relatively low through both the third and fourth quintiles. It is the poorest countries where rates of child labor explode. More than 30 percent of children work in the fifth of countries with incomes ranging from $600 to $2,000 per year. Economists Eric Edmonds and Nina Pavcnik econometrically estimate that 73 percent of the variation of child labor rates can be explained by variation in GDP per capita.17

只有当一个国家的人均年收入低于11,000美元时,我们才开始观察到童工。即便如此,在第三与第四组国家中,中等及中等偏上收入家庭的童工比例相对来说也很低。而在穷国,童工比例暴增。最为贫穷的那组国家中,人均年收入在600美元到2,000美元之间,童工比例超过了30%。经济学家Eric Edmonds 与 Nina Pavcnik 运用计量经济学测算,认为童工比例差异中的73%可由人均GDP差异来解释。⒄

Of course, correlation is not causation. But in the case of child labor and wealth, the most intuitive interpretation is that increased wealth leads to reduced child labor. After all, all countries were once poor; in the countries that became rich, child labor disappeared. Few would contend that child labor disappeared in the United States or Great Britain prior to economic growth taking place—children populated their factories much as they do in the Third World today.

当然,有相关性不代表存在因果关系。但是当我们思考童工与财富之间的关系时,最符合直觉的解读就是财富的增长减少了童工。毕竟,所有国家都有过贫穷的阶段;在那些富裕起来的国家里,童工就消失了。鲜有人认为美国或者英国的童工在经济发展之前就已经消失了——就像今日的第三世界,工厂里到处都是儿童。

A little introspection, or for that matter our moral indignation at Third World child labor, reveals that most of us desire that children, especially our own, do not work. Thus, as we become richer and can afford to allow children to have leisure and education, we choose to.

我们对历史所做的一些反省,抑或出于对第三世界童工现象的道德愤慨,这些其实都反映了我们中的大部分人不希望孩子们去工作,尤其是自己的孩子。因此,当我们变得有钱,能够为孩子们提供闲暇的生活与教育之时,我们就这样做了。

Conclusion

结论

The thought of children laboring in sweatshops is repulsive. But that does not mean we can simply think with our hearts and not our heads. Families who send their children to work in sweatshops do so because they are poor and it is the best available alternative open to them. The vast majority of children employed in countries with sweatshops work in lower-productivity sectors than manufacturing.

让儿童在血汗工厂里工作的想法令人厌恶,但这不意味着我们就该简单地让同情心泛滥,而舍弃大脑的思考。家长把孩子送去血汗工厂里工作,是因为他们太穷了,而这已是可选的选项中最好的选择。在有着血汗工厂的国家里,大多数童工所在行业的生产能力比制造业更低。

Passing trade sanctions or other laws that take away the option of children working in sweatshops only limits their options further and throws them into worse alternatives. Luckily, as families escape poverty, child labor declines. As countries become rich, child labor virtually disappears. The answer for how to cure child labor lies in the process of economic growth—a process in which sweatshops play an important role.

出台贸易制裁措施或其他法律,将这些儿童的工作机会夺走,这只会进一步限制他们的选择,陷他们于更糟糕的境地之中。值得庆幸的是,当这些家庭脱离贫困之后,童工就减少了。随着国家慢慢富裕起来,童工在事实上就会消失。如何解决童工问题的答案就在经济发展的过程之中,而血汗工厂则在其中扮演了重要角色。

Notes

注记

It is only when countries have an income less than $11,000 per year that we start to observe children in the labor force. But even here, rates of child labor remain relatively low through both the third and fourth quintiles. It is the poorest countries where rates of child labor explode. More than 30 percent of children work in the fifth of countries with incomes ranging from $600 to $2,000 per year. Economists Eric Edmonds and Nina Pavcnik econometrically estimate that 73 percent of the variation of child labor rates can be explained by variation in GDP per capita.17

只有当一个国家的人均年收入低于11,000美元时,我们才开始观察到童工。即便如此,在第三与第四组国家中,中等及中等偏上收入家庭的童工比例相对来说也很低。而在穷国,童工比例暴增。最为贫穷的那组国家中,人均年收入在600美元到2,000美元之间,童工比例超过了30%。经济学家Eric Edmonds 与 Nina Pavcnik 运用计量经济学测算,认为童工比例差异中的73%可由人均GDP差异来解释。⒄

Of course, correlation is not causation. But in the case of child labor and wealth, the most intuitive interpretation is that increased wealth leads to reduced child labor. After all, all countries were once poor; in the countries that became rich, child labor disappeared. Few would contend that child labor disappeared in the United States or Great Britain prior to economic growth taking place—children populated their factories much as they do in the Third World today.

当然,有相关性不代表存在因果关系。但是当我们思考童工与财富之间的关系时,最符合直觉的解读就是财富的增长减少了童工。毕竟,所有国家都有过贫穷的阶段;在那些富裕起来的国家里,童工就消失了。鲜有人认为美国或者英国的童工在经济发展之前就已经消失了——就像今日的第三世界,工厂里到处都是儿童。

A little introspection, or for that matter our moral indignation at Third World child labor, reveals that most of us desire that children, especially our own, do not work. Thus, as we become richer and can afford to allow children to have leisure and education, we choose to.

我们对历史所做的一些反省,抑或出于对第三世界童工现象的道德愤慨,这些其实都反映了我们中的大部分人不希望孩子们去工作,尤其是自己的孩子。因此,当我们变得有钱,能够为孩子们提供闲暇的生活与教育之时,我们就这样做了。

Conclusion

结论

The thought of children laboring in sweatshops is repulsive. But that does not mean we can simply think with our hearts and not our heads. Families who send their children to work in sweatshops do so because they are poor and it is the best available alternative open to them. The vast majority of children employed in countries with sweatshops work in lower-productivity sectors than manufacturing.

让儿童在血汗工厂里工作的想法令人厌恶,但这不意味着我们就该简单地让同情心泛滥,而舍弃大脑的思考。家长把孩子送去血汗工厂里工作,是因为他们太穷了,而这已是可选的选项中最好的选择。在有着血汗工厂的国家里,大多数童工所在行业的生产能力比制造业更低。

Passing trade sanctions or other laws that take away the option of children working in sweatshops only limits their options further and throws them into worse alternatives. Luckily, as families escape poverty, child labor declines. As countries become rich, child labor virtually disappears. The answer for how to cure child labor lies in the process of economic growth—a process in which sweatshops play an important role.

出台贸易制裁措施或其他法律,将这些儿童的工作机会夺走,这只会进一步限制他们的选择,陷他们于更糟糕的境地之中。值得庆幸的是,当这些家庭脱离贫困之后,童工就减少了。随着国家慢慢富裕起来,童工在事实上就会消失。如何解决童工问题的答案就在经济发展的过程之中,而血汗工厂则在其中扮演了重要角色。

Notes

注记

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

Free Market Food Banks

自由市场中的救济食品发放中心

作者:Alex Tabarrok @ 2015-11-03

译者:尼克基得慢(@尼克基得慢)

校对:龙泉(@ L_Stellar)

来源:http://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2015/11/free-market-food-banks.html

Feeding America, the third largest non-profit in the United States, distributes billions of pounds of food every year. Most of the food comes from large firms like Kraft, ConAgra and Walmart that have a surplus of some item and scarce warehouse space. Feeding America coordinates the supply of surplus food with the demand from food banks across the U.S..

作为美国第三大非营利性机构,“喂饱美国”每年要分发数十亿磅食品。大多数食品来自像克拉夫特、康尼格拉和沃尔玛这样产品过剩且仓储不足的大型食品公司。“喂饱美国”可调节过剩食品供给和全美救济食品发放中心【以下简称“救济中心”】需求之间的关系。

Allocating food is not an easy problem. How do you decide who gets what while taking into account local needs, local tastes, what foods the bank has already, what abilities the banks have to store food on a particular day, transportation costs and so forth. Alex Teytelboym writing at The Week (more...)

…Before 2005, Feeding America allocated food centrally, and according to its rather subjective perception of what food banks needed. Headquarters would call up the food banks in a priority order and offer them a truckload of food. Bizarrely, all food was treated more or less equally, irrespective of its nutritional content. A pound of chicken was the same as a pound of french fries. …在2005年之前,“喂饱美国”根据对救济中心需求颇为主观的感知来集中分配食物。总部会按优先顺序致电救济中心,并给他们提供一大卡车食物。离奇的是,不论营养成分如何,所有食品或多或少都被同等处理了。一磅鸡肉等同于一磅炸薯条。 If the food bank accepted the load, it paid the transportation costs and had the truck sent to them. If the food bank refused, Feeding America would judge this food bank as having lower need and push it down the priority list. Unsurprisingly, food banks went out of their way to avoid refusing food loads — even if they were already stocked with that particular food. 如果一家救济中心接受了配送,总部会付给运费让卡车把食品送给接受的中心。如果一家救济中心拒绝了,“喂饱美国”会视这家救济中心需求量较低,并把它从优先列表中除去。不出所料,所有的救济中心都特意避免拒绝食品配送——即使某类食物它们已经储存了很多。 This Soviet-style system was hugely inefficient. Some urban food banks had great access to local food donations and often ended up with a surplus of food. A lot of food rotted in places where it was not needed, while many shelves in other food banks stood empty. Feeding America simply knew too little about what their food banks needed on a given day. 这种苏联式的系统非常低效。一些城市的救济中心有很多当地的食品捐赠渠道,因此经常出现食品过剩。很多食品腐烂在不需要它们的地方,而别处救济中心的很多架子仍是空的。“喂饱美国”连某一天救济中心的需求都知之甚少。In 2005, however, a group of Chicago academics, including economists, worked with Feeding America to redesign the system using market principles. Today Feeding America no longer sends trucks of potatoes to food banks in Idaho and a pound of chicken is no longer treated the same as a pound of french fries. 然而在2005年,一群包括经济学家在内的芝加哥学者用市场准则帮助“喂饱美国”重新设计了分配系统。今天的“喂饱美国”不会再给爱达荷州的救济中心送去一车土豆了,而且一磅鸡肉跟一磅炸薯条也不再同等对待。 Instead food banks bid on food deliveries and the market discovers the internal market-prices that clear the system. The auction system even allows negative prices so that food banks can be “paid” to pick up food that is not highly desired–this helps Feeding America keep both its donors and donees happy. 救济中心转而对食品运送进行竞拍,而且市场发现了理顺整个系统的内部市场价格。这个拍卖系统甚至允许负价格,以便于救济中心可以为取走需求量不大的食物而获得报酬——这帮助“喂饱美国”同时取悦捐赠者和受捐者。 Food banks are not bidding in dollars, however, but in a new, internal currency called shares. 然而救济中心并不用美元竞拍,而是用一种新的名叫“股份”的内部货币。

Every day, each food bank is allocated a pot of fiat currency called “shares.” Food banks in areas with bigger populations and more poverty receive larger numbers of shares. Twice a day, they can use their shares to bid online on any of the 30 to 40 truckloads of food that were donated directly to Feeding America. The winners of the auction pay for the truckloads with their shares. 每个救济中心每天都会分配到一壶名为“股份”的法定货币。人口和穷人较多地区的救济中心会收到数量较多的“股份”。他们隔天就可以用自己的“股份”在线竞拍30到40卡车食品中的任意一车,这些食品都是直接捐赠给“喂饱美国”的。赢得拍卖的一方要为那车食品支付其“股份”。 Then, all the shares spent on a particular day are reallocated back to food banks at midnight. That means that food banks that did not spend their shares on a particular day would end up with more shares and thus a greater ability to bid the next day. 然后,一天内花掉的所有“股份”都会在半夜重新分配给救济中心。这意味着这一天没有花掉股份的救济中心最后会有更多“股份”,并因此在来日有更大的竞标能力。 In this way, the system has built-in fairness: If a large food bank could afford to spend a fortune on a truck of frozen chicken, its shares would show up on the balance of smaller food banks the next day. Moreover, neighboring food banks can now team up to bid jointly to reduce their transport costs. 通过这种方式,系统拥有了内在的公平性:如果一家大型救济中心在一车冻鸡肉上花了大价钱,它的“股份”就会在来日出现在小型救济中心的股份账户上。而且,临近的救济中心现在可以组团共同竞标来降低运输费用。 Initially, there was plenty of resistance. As one food bank director told Canice Prendergast, an economist advising Feeding America, “I am a socialist. That’s why I run a food bank. I don’t believe in markets. I’m not saying I won’t listen, but I am against this.” 起初有很多阻力。正如一位救济中心的主管对Canice Prendergast——一位经济学家,“喂饱美国”的顾问——所说,“我是个社会学家。这是为何由我来运营一家救济中心的原因。我不相信市场。我不是说我不会听取你们的建议,但我反对这一举措。” But the Chicago economists managed to design a market that worked even for participants who did not believe in it. Within half a year of the auction system being introduced, 97 percent of food banks won at least one load, and the amount of food allocated from Feeding America’s headquarters rose by over 35 percent, to the delight of volunteers and donors. 但是这位芝加哥经济学家尽力设计了一个连不相信它的参与者都适用的市场【编注:此处疑似埋了Niels Bohr的马蹄铁梗】。在引入拍卖系统的半年内,97%的救济中心至少竞标成功过一车食品,而且从“喂饱美国”总部分配的食品总量增长了超过35%,这是志愿者和捐赠者喜闻乐见的。Teytelboym’s very good, short account is working off a longer, more detailed paper by Canice Prendergast, The Allocation of Food to Food Banks. Teytelboym出色简短的描述都出自Canice Prendergast一篇更长更细致的论文,《救济中心的食品配给》。 Canice’s paper would be a great teaching tool in an intermediate or graduate micro economics class. Pair it with Hayek’s The Use of Knowledge in Society. Under the earlier centralized system, Feeding America didn’t know when a food bank was out of refrigerator space or which food banks had hot dogs but wanted hot dog buns and which the reverse–under the market system this information, which Hayek called “knowledge of the particular circumstances of time and place” is used and as a result less food is wasted and the food is used to satisfy more urgent needs. Canice的论文会是一份很棒的中级或者高级微观经济学课程的教学材料。最好配上哈耶克的《知识在社会中的应用》一文。在早前的集中式系统中,“喂饱美国”并不知道某个救济中心何时冰箱没空间了,或者哪家救济中心有热狗却想要热狗面包而哪家正相反——在市场系统中,这类信息——哈耶克称为“有关特定时空情境的知识”——被利用起来,因此浪费的食物更少,食物用来满足更急切的需求。 The Feeding America auction system is also the best illustration that I know of the second fundamental theorem of welfare economics. “喂饱美国”的拍卖系统也是我所知的对福利经济学第二基本定理的最好诠释。 Even monetary economics comes into play. Feeding America created a new currency and thus had to deal with the problem of the aggregate money supply. How should the supply of shares be determined so that relative prices were free to change but the price level would remain relatively stable? How could the baby-sitting co-op problem be avoided? Scott Sumner will be disappointed to learn that they choose pound targeting rather than nominal-pound targeting but some of the key issues of monetary economics are present even in this simple economy. 甚至货币经济学派上了用场。“喂饱美国”创造了一种新货币并且因此必须处理总货币供应量的问题。应如何决定“股份”的供应量以使相关价格能够自由变动而价格水平保持相对稳定?如何避免保姆合作社问题?Scott Sumner将会失望地发现,救济中心选择了以紧盯镑重而不是名义镑重为政策指引【编注:此处疑似在调戏Sumner,后者提倡一种紧盯名义GDP的货币政策。】,但是货币经济学的一些关键问题出现在了这个甚为简单的经济体中。 (编辑:辉格@whigzhou) *注:本译文未经原作者授权,本站对原文不持有也不主张任何权利,如果你恰好对原文拥有权益并希望我们移除相关内容,请私信联系,我们会立即作出响应。

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

沙特阿拉伯可能会在美国石油行业崩溃之前倒下

Saudi Arabia may go broke before the US oil industry buckles

作者:Ambrose Evans-Pritchard @ 2015-8-5

译者:Veidt(@Veidt)

校对:Tankman

来源:每日电讯报,http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/oilprices/11768136/Saudi-Arabia-may-go-broke-before-the-US-oil-industry-buckles.html

If the oil futures market is correct, Saudi Arabia will start running into trouble within two years. It will be in existential crisis by the end of the decade.

如果石油期货市场是对的,那么沙特阿拉伯将会在两年之内开始陷入麻烦。这个国家将会在这个十年的尾声时陷入一场生存危机。

The contract price of US crude oil for delivery in December 2020 is currently $62.05, implying a drastic change in the economic landscape for the Middle East and the petro-rentier states.

目前2020年12月交付的美国原油期货价格是每桶62.05美元,这个价格体现了中东地区和石油租利国家经济版图的一场剧变。

The Saudis took a huge gamble last November when they stopped supporting prices and opted instead to flood the market and drive out rivals, boosting their own output to 10.6m barrels a day (b/d) into the teeth of the downturn.

沙特人在去年11月【译注:本文作于2015年,此处指2014年11月】开始了一场豪赌,他们停止了对石油价格的支撑,转而选择在市场上倾销以挤出竞争对手,他们在市场急转直下的时候将自己的原油产量提升到了每日106万桶。

Bank of America says OPEC is now “effectively dissolved”. The cartel might as well shut down its offices in Vienna to save money.

美国银行认为OPEC目前“实际上已经解体了”。这个垄断联盟也许会关闭它在维也纳的办公室以节省资金。

If the aim was to choke the US shale industry, the Saudis have misjudged badly, just as they misjudged the growing shale threat at every stage for eight years. “It is becoming apparent that non-OPEC producers are not as responsive to low oil prices as had been thought, at least in the short-run,” said the Saudi central bank in its latest stability report.

如果这么做的目的是打击美国的页岩产业,那么沙特人就犯了个大错,就像他们在过去八年中的每个阶段都错判了成长中的页岩产业的威胁一样。“很显然那些非OPEC产油国对于低油价的反应并不像我们之前所设想的那样剧烈,至少在短期内是这样,”沙特央行在最近的稳定性报告中表示。

“The main impact has been to cut back on developmental drilling of new oil wells, rather than slowing the flow of oil from existing wells. This requires more patience,” it said.

这份报告称:“(这项政策)的主要影响是减少了新油井的开发钻探量,而并非降低现有油井的生产速度。这需要更多的耐心。”

One Saudi expert was blunter. “The policy hasn’t worked and it will never work,” he said.

一位沙特专家则更加直白。“这项政策显然没起作用,而且它也永远起不了作用,”他说。

By causing the oil price to crash, the Saudis and their Gulf allies have certainly killed off prospects for a raft of high-cost ventures in the Russian Arctic, the Gulf of Mexico, the deep waters of the mid-Atlantic, and the Canadian tar sands.

通过让油价崩溃,沙特人和他们的海湾盟友们显然杀死了那些试图在俄罗斯北极地区,墨西哥湾,大西洋中部深海和加拿大油砂中提炼原油的昂贵冒险活动。

Consultants Wood Mackenzie say the major oil and gas companies have(more...)

If the aim was to choke the US shale industry, the Saudis have misjudged badly, just as they misjudged the growing shale threat at every stage for eight years. "It is becoming apparent that non-OPEC producers are not as responsive to low oil prices as had been thought, at least in the short-run," said the Saudi central bank in its latest stability report.

如果这么做的目的是打击美国的页岩产业,那么沙特人就犯了个大错,就像他们在过去八年中的每个阶段都错判了成长中的页岩产业的威胁一样。“很显然那些非OPEC产油国对于低油价的反应并不像我们之前所设想的那样剧烈,至少在短期内是这样,”沙特央行在最近的稳定性报告中表示。

"The main impact has been to cut back on developmental drilling of new oil wells, rather than slowing the flow of oil from existing wells. This requires more patience," it said.

这份报告称:“(这项政策)的主要影响是减少了新油井的开发钻探量,而并非降低现有油井的生产速度。这需要更多的耐心。”

One Saudi expert was blunter. "The policy hasn't worked and it will never work," he said.

一位沙特专家则更加直白。“这项政策显然没起作用,而且它也永远起不了作用,”他说。

By causing the oil price to crash, the Saudis and their Gulf allies have certainly killed off prospects for a raft of high-cost ventures in the Russian Arctic, the Gulf of Mexico, the deep waters of the mid-Atlantic, and the Canadian tar sands.

通过让油价崩溃,沙特人和他们的海湾盟友们显然杀死了那些试图在俄罗斯北极地区,墨西哥湾,大西洋中部深海和加拿大油砂中提炼原油的昂贵冒险活动。

Consultants Wood Mackenzie say the major oil and gas companies have shelved 46 large projects, deferring $200bn of investments.

咨询公司Wood Machenzie表示,大型油气公司们已经将46个大型项目束之高阁,这推迟了大约2000亿美元的投资支出。

The problem for the Saudis is that US shale frackers are not high-cost. They are mostly mid-cost, and as I reported from the CERAWeek energy forum in Houston, experts at IHS think shale companies may be able to shave those costs by 45pc this year - and not only by switching tactically to high-yielding wells.

沙特人所面临的问题是,美国的页岩油气生产商们的成本并不高。正如我在休斯顿举办的CERAWeek能源论坛上所报告的,这些公司中的大多数成本都处于适中的水平,IHS公司的专家们认为这些页岩油气公司也许能在今年将这些成本削减45个百分点——而这并不仅是靠战术性地转向那些高产的油井来做到的。

Advanced pad drilling techniques allow frackers to launch five or ten wells in different directions from the same site. Smart drill-bits with computer chips can seek out cracks in the rock. New dissolvable plugs promise to save $300,000 a well. "We've driven down drilling costs by 50pc, and we can see another 30pc ahead," said John Hess, head of the Hess Corporation.

先进的井台批量钻探技术让页岩油业者能在同一处钻探点打出5口或10口不同方向的油井。植入了计算机芯片的智能钻探装置能够自动发现岩层中的裂缝。最新的可溶解油栓技术有望为每口油井节省30万美元的成本。“我们已经将钻探成本降低了百分之五十,而且我们认为目前的成本还有百分之三十的下降空间,”Hess集团总裁John Hess表示。

It was the same story from Scott Sheffield, head of Pioneer Natural Resources. "We have just drilled an 18,000 ft well in 16 days in the Permian Basin. Last year it took 30 days," he said.

先锋自然资源公司总裁Scott Sheffield也持相同看法。“我们最近在16天内在二叠纪盆地钻出了一口深达一万八千英尺的油井。而在去年,这样的工程还需要花上30天,”他说。

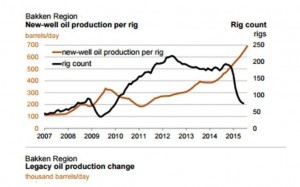

The North American rig-count has dropped to 664 from 1,608 in October but output still rose to a 43-year high of 9.6m b/d June. It has only just begun to roll over. "The freight train of North American tight oil has kept on coming," said Rex Tillerson, head of Exxon Mobil.

北美工作中的钻机数量从去年十月的1608台下降到了目前的664台,但原油产量却在今年六月升至43年来的最高水平——每日960万桶。而这仅仅只是个开始。“运送北美页岩油的货运火车正源源不断地开来,”埃克森美孚公司总裁Rex Tillerson表示。

If the aim was to choke the US shale industry, the Saudis have misjudged badly, just as they misjudged the growing shale threat at every stage for eight years. "It is becoming apparent that non-OPEC producers are not as responsive to low oil prices as had been thought, at least in the short-run," said the Saudi central bank in its latest stability report.

如果这么做的目的是打击美国的页岩产业,那么沙特人就犯了个大错,就像他们在过去八年中的每个阶段都错判了成长中的页岩产业的威胁一样。“很显然那些非OPEC产油国对于低油价的反应并不像我们之前所设想的那样剧烈,至少在短期内是这样,”沙特央行在最近的稳定性报告中表示。

"The main impact has been to cut back on developmental drilling of new oil wells, rather than slowing the flow of oil from existing wells. This requires more patience," it said.

这份报告称:“(这项政策)的主要影响是减少了新油井的开发钻探量,而并非降低现有油井的生产速度。这需要更多的耐心。”

One Saudi expert was blunter. "The policy hasn't worked and it will never work," he said.

一位沙特专家则更加直白。“这项政策显然没起作用,而且它也永远起不了作用,”他说。

By causing the oil price to crash, the Saudis and their Gulf allies have certainly killed off prospects for a raft of high-cost ventures in the Russian Arctic, the Gulf of Mexico, the deep waters of the mid-Atlantic, and the Canadian tar sands.

通过让油价崩溃,沙特人和他们的海湾盟友们显然杀死了那些试图在俄罗斯北极地区,墨西哥湾,大西洋中部深海和加拿大油砂中提炼原油的昂贵冒险活动。

Consultants Wood Mackenzie say the major oil and gas companies have shelved 46 large projects, deferring $200bn of investments.

咨询公司Wood Machenzie表示,大型油气公司们已经将46个大型项目束之高阁,这推迟了大约2000亿美元的投资支出。

The problem for the Saudis is that US shale frackers are not high-cost. They are mostly mid-cost, and as I reported from the CERAWeek energy forum in Houston, experts at IHS think shale companies may be able to shave those costs by 45pc this year - and not only by switching tactically to high-yielding wells.

沙特人所面临的问题是,美国的页岩油气生产商们的成本并不高。正如我在休斯顿举办的CERAWeek能源论坛上所报告的,这些公司中的大多数成本都处于适中的水平,IHS公司的专家们认为这些页岩油气公司也许能在今年将这些成本削减45个百分点——而这并不仅是靠战术性地转向那些高产的油井来做到的。

Advanced pad drilling techniques allow frackers to launch five or ten wells in different directions from the same site. Smart drill-bits with computer chips can seek out cracks in the rock. New dissolvable plugs promise to save $300,000 a well. "We've driven down drilling costs by 50pc, and we can see another 30pc ahead," said John Hess, head of the Hess Corporation.

先进的井台批量钻探技术让页岩油业者能在同一处钻探点打出5口或10口不同方向的油井。植入了计算机芯片的智能钻探装置能够自动发现岩层中的裂缝。最新的可溶解油栓技术有望为每口油井节省30万美元的成本。“我们已经将钻探成本降低了百分之五十,而且我们认为目前的成本还有百分之三十的下降空间,”Hess集团总裁John Hess表示。

It was the same story from Scott Sheffield, head of Pioneer Natural Resources. "We have just drilled an 18,000 ft well in 16 days in the Permian Basin. Last year it took 30 days," he said.

先锋自然资源公司总裁Scott Sheffield也持相同看法。“我们最近在16天内在二叠纪盆地钻出了一口深达一万八千英尺的油井。而在去年,这样的工程还需要花上30天,”他说。

The North American rig-count has dropped to 664 from 1,608 in October but output still rose to a 43-year high of 9.6m b/d June. It has only just begun to roll over. "The freight train of North American tight oil has kept on coming," said Rex Tillerson, head of Exxon Mobil.

北美工作中的钻机数量从去年十月的1608台下降到了目前的664台,但原油产量却在今年六月升至43年来的最高水平——每日960万桶。而这仅仅只是个开始。“运送北美页岩油的货运火车正源源不断地开来,”埃克森美孚公司总裁Rex Tillerson表示。

He said the resilience of the sister industry of shale gas should be a cautionary warning to those reading too much into the rig-count. Gas prices have collapsed from $8 to $2.78 since 2009, and the number of gas rigs has dropped 1,200 to 209. Yet output has risen by 30pc over that period.

他说,页岩气作为姊妹行业其适应能力应该引起那些过多关注钻机数量的人们的深切警醒。天然气价格已经从2009年的8美元暴跌至目前的2.78美元,而工作中的天然气钻机数量则从当时的1200台降至了目前的209台。但产量却在同一时期上升了超过三十个百分点。

Until now, shale drillers have been cushioned by hedging contracts. The stress test will come over coming months as these expire. But even if scores of over-leveraged wild-catters go bankrupt as funding dries up, it will not do OPEC any good.

直到目前,页岩钻探者们一直受到了对冲合约的保护。而未来的几个月中,随着这些合约到期,真正的压力测试将会到来。但即便这些过度使用杠杆的风险弄潮儿最终因为资金枯竭而破产,OPEC也无法从中得到任何好处。

The wells will still be there. The technology and infrastructure will still be there. Stronger companies will mop up on the cheap, taking over the operations. Once oil climbs back to $60 or even $55 - since the threshold keeps falling - they will crank up production almost instantly.

油井仍然在那里。技术和基础设施也仍然在那里。更加强大的公司将会廉价扫货,并接管他们的生意。一旦油价重新回到每桶60美元甚至55美元——这个阈值正在持续降低——他们将会立即重新启动钻机开始生产。

OPEC now faces a permanent headwind. Each rise in price will be capped by a surge in US output. The only constraint is the scale of US reserves that can be extracted at mid-cost, and these may be bigger than originally supposed, not to mention the parallel possibilities in Argentina and Australia, or the possibility for "clean fracking" in China as plasma pulse technology cuts water needs.

OPEC目前面临着一个挥之不去的困境。每一波油价上涨就会被一波美国原油产量的激增抵消。对此的唯一限制是全美能够以适中成本开采的原油总储量,而这个数字则很可能比人们之前设想的要大,更不用提在阿根廷和澳大利亚的那些类似的可供开采储量,还有中国未来因等离子脉冲技术降低了对水量的需求,实现“清洁开采”的可能性。

Mr Sheffield said the Permian Basin in Texas could alone produce 5-6m b/d in the long-term, more than Saudi Arabia's giant Ghawar field, the biggest in the world.

Sheffield先生表示,单单是德州的二叠纪盆地在长期内的日产出量就能达到500到600万桶,而这个数字比目前世界上最大的石油产区——沙特阿拉伯的大Ghawar油田的产出还要大。

Saudi Arabia is effectively beached. It relies on oil for 90pc of its budget revenues. There is no other industry to speak of, a full fifty years after the oil bonanza began.

沙特阿拉伯这艘大船实际上已经搁浅了。这个国家预算收入中的90%都依赖石油。而在经历了整整50年的石油大繁荣之后,它并没有发展出任何其它值得一提的产业。

He said the resilience of the sister industry of shale gas should be a cautionary warning to those reading too much into the rig-count. Gas prices have collapsed from $8 to $2.78 since 2009, and the number of gas rigs has dropped 1,200 to 209. Yet output has risen by 30pc over that period.

他说,页岩气作为姊妹行业其适应能力应该引起那些过多关注钻机数量的人们的深切警醒。天然气价格已经从2009年的8美元暴跌至目前的2.78美元,而工作中的天然气钻机数量则从当时的1200台降至了目前的209台。但产量却在同一时期上升了超过三十个百分点。

Until now, shale drillers have been cushioned by hedging contracts. The stress test will come over coming months as these expire. But even if scores of over-leveraged wild-catters go bankrupt as funding dries up, it will not do OPEC any good.

直到目前,页岩钻探者们一直受到了对冲合约的保护。而未来的几个月中,随着这些合约到期,真正的压力测试将会到来。但即便这些过度使用杠杆的风险弄潮儿最终因为资金枯竭而破产,OPEC也无法从中得到任何好处。

The wells will still be there. The technology and infrastructure will still be there. Stronger companies will mop up on the cheap, taking over the operations. Once oil climbs back to $60 or even $55 - since the threshold keeps falling - they will crank up production almost instantly.

油井仍然在那里。技术和基础设施也仍然在那里。更加强大的公司将会廉价扫货,并接管他们的生意。一旦油价重新回到每桶60美元甚至55美元——这个阈值正在持续降低——他们将会立即重新启动钻机开始生产。

OPEC now faces a permanent headwind. Each rise in price will be capped by a surge in US output. The only constraint is the scale of US reserves that can be extracted at mid-cost, and these may be bigger than originally supposed, not to mention the parallel possibilities in Argentina and Australia, or the possibility for "clean fracking" in China as plasma pulse technology cuts water needs.

OPEC目前面临着一个挥之不去的困境。每一波油价上涨就会被一波美国原油产量的激增抵消。对此的唯一限制是全美能够以适中成本开采的原油总储量,而这个数字则很可能比人们之前设想的要大,更不用提在阿根廷和澳大利亚的那些类似的可供开采储量,还有中国未来因等离子脉冲技术降低了对水量的需求,实现“清洁开采”的可能性。

Mr Sheffield said the Permian Basin in Texas could alone produce 5-6m b/d in the long-term, more than Saudi Arabia's giant Ghawar field, the biggest in the world.

Sheffield先生表示,单单是德州的二叠纪盆地在长期内的日产出量就能达到500到600万桶,而这个数字比目前世界上最大的石油产区——沙特阿拉伯的大Ghawar油田的产出还要大。

Saudi Arabia is effectively beached. It relies on oil for 90pc of its budget revenues. There is no other industry to speak of, a full fifty years after the oil bonanza began.

沙特阿拉伯这艘大船实际上已经搁浅了。这个国家预算收入中的90%都依赖石油。而在经历了整整50年的石油大繁荣之后,它并没有发展出任何其它值得一提的产业。

Citizens pay no tax on income, interest, or stock dividends. Subsidized petrol costs twelve cents a litre at the pump. Electricity is given away for 1.3 cents a kilowatt-hour. Spending on patronage exploded after the Arab Spring as the kingdom sought to smother dissent.

该国的国民不需要为他们的收入,利息或者股利交税。在加油站可以用每升12美分的补贴价格购买汽油。每千瓦时的电价仅仅是1.3美分。在“阿拉伯之春”开始之后,由于王室试图平息民间的不满情绪,该国用于收买支持的开支也迅速地增长。

The International Monetary Fund estimates that the budget deficit will reach 20pc of GDP this year, or roughly $140bn. The 'fiscal break-even price' is $106.

据国际货币基金组织估计,沙特的财政赤字将在今年占到GDP的20%,也就是大约1400亿美元。而让该国的财政收支达到均衡的油价水平是每桶106美元。

Far from retrenching, King Salman is spraying money around, giving away $32bn in a coronation bonus for all workers and pensioners.

而当今沙特国王萨勒曼却完全没有想要缩减开支的意思,反而四处撒钱,单单是在一次加冕礼上,他就为全国的所有工人和退休者发放了320亿美元的奖金。

He has launched a costly war against the Houthis in Yemen and is engaged in a massive military build-up - entirely reliant on imported weapons - that will propel Saudi Arabia to fifth place in the world defence ranking.

此外,他还对也门的胡塞武装发动了一场代价高昂的战争,并且大肆扩张军备——沙特的军备完全依赖从外国进口武器——这会使沙特的军费开支排到全球第5位。

The Saudi royal family is leading the Sunni cause against a resurgent Iran, battling for dominance in a bitter struggle between Sunni and Shia across the Middle East. "Right now, the Saudis have only one thing on their mind and that is the Iranians. They have a very serious problem. Iranian proxies are running Yemen, Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon," said Jim Woolsey, the former head of the US Central Intelligence Agency.

沙特王室还需要肩负领导逊尼派对抗东山再起的伊朗的重任,为争夺霸权,整个中东地区的逊尼派和什叶派之间展开了艰苦的斗争。“现在沙特人满脑子都只想着一件事情,那就是来自伊朗人的威胁。他们面临着一个非常严峻的问题,伊朗的代理人目前正控制着也门,叙利亚,伊拉克和黎巴嫩,”美国中央情报局前任局长吉姆·伍尔西表示。

Citizens pay no tax on income, interest, or stock dividends. Subsidized petrol costs twelve cents a litre at the pump. Electricity is given away for 1.3 cents a kilowatt-hour. Spending on patronage exploded after the Arab Spring as the kingdom sought to smother dissent.

该国的国民不需要为他们的收入,利息或者股利交税。在加油站可以用每升12美分的补贴价格购买汽油。每千瓦时的电价仅仅是1.3美分。在“阿拉伯之春”开始之后,由于王室试图平息民间的不满情绪,该国用于收买支持的开支也迅速地增长。

The International Monetary Fund estimates that the budget deficit will reach 20pc of GDP this year, or roughly $140bn. The 'fiscal break-even price' is $106.

据国际货币基金组织估计,沙特的财政赤字将在今年占到GDP的20%,也就是大约1400亿美元。而让该国的财政收支达到均衡的油价水平是每桶106美元。

Far from retrenching, King Salman is spraying money around, giving away $32bn in a coronation bonus for all workers and pensioners.

而当今沙特国王萨勒曼却完全没有想要缩减开支的意思,反而四处撒钱,单单是在一次加冕礼上,他就为全国的所有工人和退休者发放了320亿美元的奖金。

He has launched a costly war against the Houthis in Yemen and is engaged in a massive military build-up - entirely reliant on imported weapons - that will propel Saudi Arabia to fifth place in the world defence ranking.

此外,他还对也门的胡塞武装发动了一场代价高昂的战争,并且大肆扩张军备——沙特的军备完全依赖从外国进口武器——这会使沙特的军费开支排到全球第5位。

The Saudi royal family is leading the Sunni cause against a resurgent Iran, battling for dominance in a bitter struggle between Sunni and Shia across the Middle East. "Right now, the Saudis have only one thing on their mind and that is the Iranians. They have a very serious problem. Iranian proxies are running Yemen, Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon," said Jim Woolsey, the former head of the US Central Intelligence Agency.

沙特王室还需要肩负领导逊尼派对抗东山再起的伊朗的重任,为争夺霸权,整个中东地区的逊尼派和什叶派之间展开了艰苦的斗争。“现在沙特人满脑子都只想着一件事情,那就是来自伊朗人的威胁。他们面临着一个非常严峻的问题,伊朗的代理人目前正控制着也门,叙利亚,伊拉克和黎巴嫩,”美国中央情报局前任局长吉姆·伍尔西表示。

Money began to leak out of Saudi Arabia after the Arab Spring, with net capital outflows reaching 8pc of GDP annually even before the oil price crash. The country has since been burning through its foreign reserves at a vertiginous pace.

在“阿拉伯之春”发生后,资本开始流出沙特阿拉伯,即使在油价崩溃之前,每年资本净流出也占到了GDP的8%。从那时开始,该国的外汇储备就以惊人地速度直线下降。

The reserves peaked at $737bn in August of 2014. They dropped to $672 in May. At current prices they are falling by at least $12bn a month.

沙特的外汇储备在2014年8月达到峰值7370亿美元。而到今年5月,这个数字下降到了6720亿美元。以目前的汇率计算,沙特的外汇储备每月至少会下降120亿美元。【编注:2016年4月 已降至5720亿美元】

Money began to leak out of Saudi Arabia after the Arab Spring, with net capital outflows reaching 8pc of GDP annually even before the oil price crash. The country has since been burning through its foreign reserves at a vertiginous pace.

在“阿拉伯之春”发生后,资本开始流出沙特阿拉伯,即使在油价崩溃之前,每年资本净流出也占到了GDP的8%。从那时开始,该国的外汇储备就以惊人地速度直线下降。

The reserves peaked at $737bn in August of 2014. They dropped to $672 in May. At current prices they are falling by at least $12bn a month.

沙特的外汇储备在2014年8月达到峰值7370亿美元。而到今年5月,这个数字下降到了6720亿美元。以目前的汇率计算,沙特的外汇储备每月至少会下降120亿美元。【编注:2016年4月 已降至5720亿美元】

Khalid Alsweilem, a former official at the Saudi central bank and now at Harvard University, said the fiscal deficit must be covered almost dollar for dollar by drawing down reserves.

沙特央行的一位前任官员Khalid Alsweilem(目前在哈佛大学担任研究员)表示,沙特政府财政赤字中的几乎每一美元都需要以外汇储备的同等下降为代价来弥补。

The Saudi buffer is not particularly large given the country's fixed exchange system. Kuwait, Qatar, and Abu Dhabi all have three times greater reserves per capita. "We are much more vulnerable. That is why we are the fourth rated sovereign in the Gulf at AA-. We cannot afford to lose our cushion over the next two years," he said.

在该国的固定汇率体系之下,留给沙特人的缓冲余地并不是很大。科威特,卡塔尔和阿布扎比所拥有的人均外汇储备是沙特的三倍。“我们相对而言要脆弱得多。这就是为何我们的主权债评级在海湾地区只排第四,评级水平也仅是AA-。在未来两年中,我们承受不起失去外汇储备缓冲的后果,”他说。

Standard & Poor's lowered its outlook to "negative" in February. "We view Saudi Arabia's economy as undiversified and vulnerable to a steep and sustained decline in oil prices," it said.

标普在今年二月将沙特主权债务的评级展望降为“负面”。“我们认为在油价持续急剧下降的过程中,沙特阿拉伯的经济没有多元化,并且十分脆弱,”标普在他们的报告中表示。

Mr Alsweilem wrote in a Harvard report that Saudi Arabia would have an extra trillion of assets by now if it had adopted the Norwegian model of a sovereign wealth fund to recyle the money instead of treating it as a piggy bank for the finance ministry. The report has caused storm in Riyadh.

Alsweilem先生在哈佛大学的一份报告中写道,如果沙特之前采用挪威的主权财富基金模式让外汇储备循环投资,而不是像他们所做的那样仅仅把它当作财政部的一头现金奶牛,目前沙特阿拉伯的资产也许会多出1万亿美元。这份报告在沙特首都利雅得引发了风暴。

"We were lucky before because the oil price recovered in time. But we can't count on that again," he said.

“上一次我们很幸运,因为油价适时地恢复了。但是这次我们不能再次指望同样的事情会,”他说。

OPEC have left matters too late, though perhaps there is little they could have done to combat the advances of American technology.

OPEC做出反应时已经太晚了,虽然即使早一些意识到问题,他们也做不了太多事情来对抗美国的技术进步。

In hindsight, it was a strategic error to hold prices so high, for so long, allowing shale frackers - and the solar industry - to come of age. The genie cannot be put back in the bottle.

事后看来,让油价在如此长的时间维持在这么高的位置实际上是一个战略性错误,这样那些页岩油气的勘探者们——还有太阳能产业——就能够成长壮大。一旦被放出来,你就无法再将精灵放回瓶子里了。

The Saudis are now trapped. Even if they could do a deal with Russia and orchestrate a cut in output to boost prices - far from clear - they might merely gain a few more years of high income at the cost of bringing forward more shale production later on.

沙特人如今陷入了困境。即使他们能与俄罗斯达成一致共同减产以支撑油价——虽然这样的愿景目前看来一点也不清晰——这也仅仅能让他们享受多几年的高收入,而这样做的代价却是在未来面临更多的页岩油产出的竞争。

Yet on the current course their reserves may be down to $200bn by the end of 2018. The markets will react long before this, seeing the writing on the wall. Capital flight will accelerate.

而如果当前的趋势维持下去,沙特的外汇储备将在2018年底前降至2000亿美元以下。一旦前景明白无误了,市场会在它成为现实前就早早做出反应。资本外流将会加速。

The government can slash investment spending for a while - as it did in the mid-1980s - but in the end it must face draconian austerity. It cannot afford to prop up Egypt and maintain an exorbitant political patronage machine across the Sunni world.

沙特政府可以在一段时间内削减资本开支——就像它在1980年代中期所做的那样——但最终它将面临严峻的紧缩。沙特将无法负担起支撑埃及政权并在逊尼派穆斯林世界里维持一台昂贵的资助机器的开支。

Social spending is the glue that holds together a medieval Wahhabi regime at a time of fermenting unrest among the Shia minority of the Eastern Province, pin-prick terrorist attacks from ISIS, and blowback from the invasion of Yemen.

庞大的社会开支是将一个仍然处在中世纪状态的瓦哈比政权维系在一起的粘合剂,这个政权正面临着东部省份的什叶少数派中正在发酵的动荡,ISIS时而发动的针刺般的恐怖袭击,还有入侵也门所带来的反作用力。

Diplomatic spending is what underpins the Saudi sphere of influence in a Middle East suffering its own version of Europe's Thirty Year War, and still reeling from the after-shocks of a crushed democratic revolt.

庞大的外交开支则是维系沙特在中东地区影响力的基础,而目前中东地区正在经历着类似欧洲“三十年战争”般的苦难,同时还在蹒跚地试图爬出镇压民主反抗运动带来的余震。

We may yet find that the US oil industry has greater staying power than the rickety political edifice behind OPEC.

我们也许会发现,虽然同样处在低谷中,但相比OPEC身后的那座虚弱的政治大厦,美国的石油行业其实拥有着更强的生命力。

(编辑:辉格@whigzhou)

*注:本译文未经原作者授权,本站对原文不持有也不主张任何权利,如果你恰好对原文拥有权益并希望我们移除相关内容,请私信联系,我们会立即作出响应。

Khalid Alsweilem, a former official at the Saudi central bank and now at Harvard University, said the fiscal deficit must be covered almost dollar for dollar by drawing down reserves.

沙特央行的一位前任官员Khalid Alsweilem(目前在哈佛大学担任研究员)表示,沙特政府财政赤字中的几乎每一美元都需要以外汇储备的同等下降为代价来弥补。

The Saudi buffer is not particularly large given the country's fixed exchange system. Kuwait, Qatar, and Abu Dhabi all have three times greater reserves per capita. "We are much more vulnerable. That is why we are the fourth rated sovereign in the Gulf at AA-. We cannot afford to lose our cushion over the next two years," he said.

在该国的固定汇率体系之下,留给沙特人的缓冲余地并不是很大。科威特,卡塔尔和阿布扎比所拥有的人均外汇储备是沙特的三倍。“我们相对而言要脆弱得多。这就是为何我们的主权债评级在海湾地区只排第四,评级水平也仅是AA-。在未来两年中,我们承受不起失去外汇储备缓冲的后果,”他说。

Standard & Poor's lowered its outlook to "negative" in February. "We view Saudi Arabia's economy as undiversified and vulnerable to a steep and sustained decline in oil prices," it said.

标普在今年二月将沙特主权债务的评级展望降为“负面”。“我们认为在油价持续急剧下降的过程中,沙特阿拉伯的经济没有多元化,并且十分脆弱,”标普在他们的报告中表示。

Mr Alsweilem wrote in a Harvard report that Saudi Arabia would have an extra trillion of assets by now if it had adopted the Norwegian model of a sovereign wealth fund to recyle the money instead of treating it as a piggy bank for the finance ministry. The report has caused storm in Riyadh.

Alsweilem先生在哈佛大学的一份报告中写道,如果沙特之前采用挪威的主权财富基金模式让外汇储备循环投资,而不是像他们所做的那样仅仅把它当作财政部的一头现金奶牛,目前沙特阿拉伯的资产也许会多出1万亿美元。这份报告在沙特首都利雅得引发了风暴。

"We were lucky before because the oil price recovered in time. But we can't count on that again," he said.

“上一次我们很幸运,因为油价适时地恢复了。但是这次我们不能再次指望同样的事情会,”他说。

OPEC have left matters too late, though perhaps there is little they could have done to combat the advances of American technology.

OPEC做出反应时已经太晚了,虽然即使早一些意识到问题,他们也做不了太多事情来对抗美国的技术进步。

In hindsight, it was a strategic error to hold prices so high, for so long, allowing shale frackers - and the solar industry - to come of age. The genie cannot be put back in the bottle.

事后看来,让油价在如此长的时间维持在这么高的位置实际上是一个战略性错误,这样那些页岩油气的勘探者们——还有太阳能产业——就能够成长壮大。一旦被放出来,你就无法再将精灵放回瓶子里了。

The Saudis are now trapped. Even if they could do a deal with Russia and orchestrate a cut in output to boost prices - far from clear - they might merely gain a few more years of high income at the cost of bringing forward more shale production later on.

沙特人如今陷入了困境。即使他们能与俄罗斯达成一致共同减产以支撑油价——虽然这样的愿景目前看来一点也不清晰——这也仅仅能让他们享受多几年的高收入,而这样做的代价却是在未来面临更多的页岩油产出的竞争。

Yet on the current course their reserves may be down to $200bn by the end of 2018. The markets will react long before this, seeing the writing on the wall. Capital flight will accelerate.

而如果当前的趋势维持下去,沙特的外汇储备将在2018年底前降至2000亿美元以下。一旦前景明白无误了,市场会在它成为现实前就早早做出反应。资本外流将会加速。

The government can slash investment spending for a while - as it did in the mid-1980s - but in the end it must face draconian austerity. It cannot afford to prop up Egypt and maintain an exorbitant political patronage machine across the Sunni world.

沙特政府可以在一段时间内削减资本开支——就像它在1980年代中期所做的那样——但最终它将面临严峻的紧缩。沙特将无法负担起支撑埃及政权并在逊尼派穆斯林世界里维持一台昂贵的资助机器的开支。

Social spending is the glue that holds together a medieval Wahhabi regime at a time of fermenting unrest among the Shia minority of the Eastern Province, pin-prick terrorist attacks from ISIS, and blowback from the invasion of Yemen.

庞大的社会开支是将一个仍然处在中世纪状态的瓦哈比政权维系在一起的粘合剂,这个政权正面临着东部省份的什叶少数派中正在发酵的动荡,ISIS时而发动的针刺般的恐怖袭击,还有入侵也门所带来的反作用力。

Diplomatic spending is what underpins the Saudi sphere of influence in a Middle East suffering its own version of Europe's Thirty Year War, and still reeling from the after-shocks of a crushed democratic revolt.

庞大的外交开支则是维系沙特在中东地区影响力的基础,而目前中东地区正在经历着类似欧洲“三十年战争”般的苦难,同时还在蹒跚地试图爬出镇压民主反抗运动带来的余震。

We may yet find that the US oil industry has greater staying power than the rickety political edifice behind OPEC.

我们也许会发现,虽然同样处在低谷中,但相比OPEC身后的那座虚弱的政治大厦,美国的石油行业其实拥有着更强的生命力。

(编辑:辉格@whigzhou)

*注:本译文未经原作者授权,本站对原文不持有也不主张任何权利,如果你恰好对原文拥有权益并希望我们移除相关内容,请私信联系,我们会立即作出响应。

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

A Cost-Benefit Analysis of Government Compensation of Kidney Donors

政府补贴捐肾者的成本效益分析

作者:Alex Tabarrok @ 2015-11-25

译者:Eartha(@王小贰_Eartha)

校对:小册子(@昵称被抢的小册子)

来源:Marginal Revolution,http://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2015/11/a-cost-bene%EF%AC%81t-analysis-of-government-compensation-of-kidney-donors.html

The latest issue of the American Journal of Transplantation has an excellent and comprehensive cost-benefit analysis of paying kidney donors by Held, McCormick, Ojo, and Roberts.

最新一期【(more...)

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

【2016-06-01】

@whigzhou: 看过《大空头》:虽然下了点功夫,但还是错的离谱,Margin Call仍是有关金融题材唯一好电影 ★★★

1)市场上永远不缺看空、唱空、做空者,更有无数泡沫论、危机论、末日论者,

2)对房产泡沫和次贷风险的警告早就存在了,绝非一小撮火眼金睛的怪人聪明人的离经叛道之辞,

3)看空和做空是完全不同的两码事,后者需要对崩盘时间的准确判断,危机晚几个月爆发,跳楼的可能就是你了,

4)所以这根本不是一小撮聪明人/头脑清醒者与其他所有傻瓜/混蛋/疯子之间互搏的问题,果若如此,就不会有金融市场了,

5)次贷危机的始作俑者就是政府,放贷机构当然是非常起劲且不负责任的放出了大量劣质房贷,但他们敢这么做就是因为(more...)

【2016-05-23】

1)达尔萨斯主义者(Darthusian)和古典自由主义者的根本区别在于:不许诺一个共同富裕普遍康乐的前景,并认为那注定是个虚假的许诺,

2)尽管我们相信(也乐意称颂)自由市场可以最大限度的拓展合作共赢的领域,也承认(统计上)自由社会的最穷困阶层也比非自由社会的普通人状况更好,但不会否认自由竞争终究会有失败者,自由化甚至可能在绝对水平上恶化一些人的处境,

3)马尔萨斯法则为这一判断提供了兜底保证,尽管不是唯一理由,

4)达尔文的启示在于,这完全不是(more...)

【2016-05-13】

@海德沙龙 《自由市场环保主义》 环境问题向来都被视为市场失灵的一种表现,许多经济学家也认为,市场本身无法处理像环境污染这样的“外部性”问题,良好环境是一种“公共品”,只能由政府提供(以管制或庇古税的方式),可实际上,无论是理论还是经验都告诉我们,自由市场能够处理环境问题

@whigzhou: 福利经济学作为一种思考问题的方式是有益的,像外部性、公共品、帕累托最优等概念,对不同税种之经济性质的分析,等等,但许多自以为是的福利经济学家总(more...)

【2016-05-07】

@whigzhou: 从老弗里德曼那辈开始,libertarians总是宣称18/19世纪的英国和美国有多么自由放任,许多追随者也人云亦云,他们的用意很好,但说法是错的,实际上,即便西方世界中最自由的部分,(除了少数袖珍国之外)距离古典自由主义的理想制度始终很遥远,只不过那时候国家干预经济和私人生活的方式不同而已。

@whigzhou: 略举几点:1)自由贸易,古典自由主义时代推动自由贸易的主要方式是破除非关税壁垒,而关税始终很高,各国财政对关税的依赖也比现在高得多,关税大幅下降到个位数水平是二战后的事(more...)