【2018-05-16】

决定某一时代某社会之学术活动整体面貌的首要因素是,最具天赋的万分之一人口,都被吸引到哪些学科去了,更一般而言,决定某一社会之文化面貌的首要因素是,最具天赋的万分之一人口,都被吸引到哪些领域的智力活动中去了。

【2020-06-14】

隐约感觉,各学科之间的发展可能存在某些联动关系,比如:1)一些对智力要求极高的学科,比如理论物理,若遭遇平台期,看不到取得卓著成就的前景,就会提升其(more...)

【2018-05-16】

决定某一时代某社会之学术活动整体面貌的首要因素是,最具天赋的万分之一人口,都被吸引到哪些学科去了,更一般而言,决定某一社会之文化面貌的首要因素是,最具天赋的万分之一人口,都被吸引到哪些领域的智力活动中去了。

【2020-06-14】

隐约感觉,各学科之间的发展可能存在某些联动关系,比如:1)一些对智力要求极高的学科,比如理论物理,若遭遇平台期,看不到取得卓著成就的前景,就会提升其(more...)

【2018-02-28】

别的不说,引入定量方法至少可以把大批文青从一个学科里清除出去……近年来读的人类学著作中靠谱的比例越来越高,甚至历史学也是,这当然离不开新达尔文主义的持续渗透,但新统计学工具和定量方法的大量运用显然也起了很大作用,让四则运算都头疼的文青弄明白什么叫百分位、标准差、基尼系数、Herfindahl系数、p值、贝叶斯推断……确实勉为其难了。

没有啊,我挺喜欢文青的,只要你们专心于文艺、风(more...)

【2018-02-24】

@innesfry: 在二战之前,医学跟巫术几乎没有太大区别。医生杀死的人恐怕比救活的还多。

@whigzhou: 库克船长的柠檬,Pelletier的奎宁, Lister的消毒剂,伦敦的抗霍乱,洛克菲勒的事业……都远在二战之前 //@whigzhou: Cochran大叔懂得很多,知道的也很多,但也不能全信,他在这件事情上说的太过头了,随便想几个例子就会发现不对劲。

@whigzhou: 这些例子都是以明确的知识积累为基础,不是瞎蒙瞎撞的结果(more...)

科学的退化

Scientific Regress

作者:William A. Wilson @ 2016-05

译者:小聂(@PuppetMaster)

校对:龙泉

来源:First Things,https://www.firstthings.com/article/2016/05/scientific-regress

The problem with science is that so much of it simply isn’t. Last summer, the Open Science Collaboration announced that it had tried to replicate one hundred published psychology experiments sampled from three of the most prestigious journals in the field. Scientific claims rest on the idea that experiments repeated under nearly identical conditions ought to yield approximately the same results, but until very recently, very few had bothered to check in a systematic way whether this was actually the case.

科学研究的问题在于,它们中的很大一部分其实根本不科学。去年夏天,开放科学合作组织(OSC)宣布他们曾试图重复100个选自三本行业权威杂志上的心理学实验。科学论断建基于这样一个观念:在几乎相同的条件下重复实验,其结果也应该相同。但是直到最近为止,此前几乎没有人系统性地验证是不是真的如此。

The OSC was the biggest attempt yet to check a field’s results, and the most shocking. In many cases, they had used original experimental materials, and sometimes even performed the experiments under the guidance of the original researchers. Of the studies that had originally reported positive results, an astonishing 65 perce(more...)

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

RECKONING WITH THE PAST

和过去做个了结

作者:MICHAEL INZLICHT @ 2016-02-29

译者:龟海海(@龟海海)

校对:混乱阈值(@混乱阈值)

来源:MICHAEL INZLICHT的博客,http://michaelinzlicht.com/getting-better/2016/2/29/reckoning-with-the-past

Sometimes I wonder if I should be fixing myself more to drink.

有时候我辗转反侧,不知是否该借酒消愁。

No, this is not going to be an optimistic post.

没错,这不是一篇鸡汤文。

If you want bubbles and sunshine, please see my friend Simine Vazire’s post on why she is feeling optimistic about things. If you want nuance and balance, see my co-moderator Alison Ledgerwood’s new blog*. Instead, if you will allow me, I want to wallow.

如果你想要泡沫和阳光,我朋友Simine Vazire的文章会告诉你为什么她如此积极乐观。如果你想要情绪间的微妙平衡,看我同僚Alison Ledgerwood的新博客。而我,只想好好吐槽一番。

I have so many feelings about the situation we’re in, and sometimes the weight of it all breaks my heart. I know I’m being intemperate, not thinking clearly, but I feel that it is only when we feel badly, when we acknowledge and, yes, grieve for yesterday, that we can allow for a better tomorrow. I want a better tomorrow, I want social psychology to change. But, the only way we can really change is if we reckon with our past, coming clean that we erred; and erred badly.

我对我们现在的处境有太多的感触,这有时沉重得让我心力交瘁。我知道我失去了自控,头脑不清楚。但我觉得只有当我们直面昨日,为昨日沉痛伤感,才能拥有美好的明天。我渴望美好的明天,我希望社会心理学能改变。但是,唯一能使我们真正改变的是和过去做个了结,坦白过去所犯的严重错误。

To be clear: I am in love with social psychology. I am writing here because I am still in love with social psychology. Yet, I am dismayed that so many of us are dismissing or justifying all those small (and not so small) signs that things are just not right, that things are not what they seem. “Carry-on, folks, nothing to see here,” is what some of us seem to be saying.

首先声明:我热爱社会心理学。我在这儿码字就是因为我依然爱它。然而,让我感到泄气的是,尽管很多微小(其实并非如此微小)的迹象表明情况不妙且另有隐情,我们之中许多人却对所有这些迹象视而不见或想出种种理由开脱。“继续,伙计,这儿没啥好看的,”我们中有些人似乎在这么说着。(more...)

········

*In case you haven’t heard, Alison started a wonderful Facebook discussion group that I have the privilege of co-moderating. If you’re tired of bickering and incivility, but still want a place to discuss ideas, PsychMAP just might be for for you. 再次安利一下,Alison开了一个非常不错的脸书讨论组,我也有幸在其中参与共同主持。如果你厌倦了互撕,但仍想找个地方抒发讨论,PsychMAP可能恰好就适合你。 (编辑:辉格@whigzhou) *注:本译文未经原作者授权,本站对原文不持有也不主张任何权利,如果你恰好对原文拥有权益并希望我们移除相关内容,请私信联系,我们会立即作出响应。——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

Schizophrenia: No Smoking Gun

精神分裂症:缺乏“冒烟”的确凿证据

作者:Scott Alexander @ 2016-01-11

译者:沈沉(@你在何地-sxy)

校对:小册子(@昵称被抢的小册子)

来源:Slate Star Codex,http://slatestarcodex.com/2016/01/11/schizophrenia-no-smoking-gun/

[Note: despite how some people are spinning this, tobacco is still really really bad and you should not smoke it]

【请注意:尽管许多人言之凿凿,但烟草真的真的还是很不好,不应该抽烟。】

I.

Schizophrenics smoke. A lot. Depending on the study, about 60-80% of schizophrenics smoke, compared to only about 20% of the general population. And they spend on average about 27% (!) of their income on cigarettes. Even allowing that schizophrenics don’t make much income, that’s a lot of money. Sure, schizophrenics are often poor and undereducated and have other risk factors for smoking – but even after you control for this, the effect is still pretty strong.

精神分裂症患者抽烟,而且很多。根据某项研究,大约60%至80%的精神分裂症患者会抽烟,与之相比,总人口中只有约20%。而且,他们在烟草上的花费大约占到其收入的27%(!)。即便考虑到精神分裂症患者收入不高,这也是一大笔钱。无疑,精神分裂症患者通常都很穷、受教育程度不高,并且还有其他导致其吸烟的风险因素,但即便把所有这些都加以控制,精神分裂症与抽烟之间的统计关系还是很强。

Various people have come up with various explanations. Cognitively-minded people say that schizophrenics smoke as a maladaptive coping strategy for the anxiety caused by their condition. Pharmacologically-minded people say that schizophrenics smoke because smoking accelerates the metabolism of antipsychotic drugs and so makes their side effects go away faster. Pragmatically-minded people say that schizophrenics smoke because they’re stuck in institutions with nothing to do all day. No points for guessing what the Freudians say.

许多人已经为此提出过许多各种解释。关注认知的人说,精神分裂症患者抽烟,是对该疾病所致焦虑的不良应对策略。关注药理的人会说,他们抽烟是因为抽烟会加快抗精神病药物的代谢,从而能够促使其副作用更快消失。更为务实的人会说,他们抽烟是因为他们被困在了整日无所事事的社会福利机构里面。猜测弗洛伊德主义者的说法就没必要了。

But all these theories have problems. Sure, schizophrenics are often institutionalized, but even the ones at home smoke a lot. Sure, some schizophrenics are often on antipsychotics, but even the ones who aren’t on meds smoke a lot. Sure, schizophrenics are anxious, but we don’t see people with Generalized Anxiety Disorder having 80% smoking rates.

但所有这些理论都存在问题。毫无疑问,精神分裂症患者通常都被社会福利机构收容,但即便是那些散居在家的也抽很多烟。毫无疑问,有些精神分裂症患者经常服用抗精神病药,但即便是那些不服药的也抽很多烟。毫无疑问,精神分裂症患者很焦虑,但我们并没有在患有广泛性焦虑障碍的人群中看到80%的吸烟率。

As usual, (more...)

Cigarette smoking might be a hitherto neglected modifiable risk factor for psychosis, but confounding and reverse causality are possible. Notwithstanding, in view of the clear benefits of smoking cessation programs in this population, every effort should be made to implement change in smoking habits in this group of patients. 吸烟可能是引发精神病的可改造风险因素之一,这一点迄今为止一直为人所忽略。但是,混杂偏差和反向因果关系也有可能存在。尽管如此,考虑到在这一人群中实施戒烟计划的明显好处,我们应该全面努力,促使这一病患群体改变吸烟习惯。Clear benefits! Every effort! Aaaaaaah! 明显好处!全面努力!啊哈哈哈哈! I mean, I know where they (and the Lancet editors, who write a glowing comment backing them up) are coming from. Smoking is bad because lung cancer, COPD, etc. But now we have these things called e-cigarettes! They deliver nicotine without tobacco! As far as anyone knows they carry vastly less risk of cancer, COPD, etc. If nicotine actually prevents schizophrenia rather than causing it, that is the sort of thing we should really want to know. And instead we’re just getting this “We should make schizophrenia patients stop smoking, because smoking is bad”. 我说,我知道他们(以及《柳叶刀》的编辑们,他们写了篇热情洋溢的评论支持前者)的出发点在哪儿。吸烟不好,因为会导致肺癌、慢性阻塞性肺炎等等。但我们现在已经有了所谓的电子烟!它们无需烟草就能提供尼古丁。如果尼古丁确实会预防而不是导致精神分裂症,这种事应该是我们确实想要明白知晓的。但是,我们听到的却是这样一些话:“我们应该让精神分裂症患者停止抽烟,因为抽烟不好。” Look. I am not going to come out and say that there’s great evidence that nicotine decreases schizophrenia risk. There’s one study, which other studies contradict. I happen to think that the one study looks better than its competitors, but that’s my opinion and I have nowhere near the evidence I would need to feel really strongly about this. 注意,我不是跳出来说有很强的证据表明尼古丁有助于减少精神分裂症患病风险。有一项研究这么说,还有许多研究跟它有抵触。我只是凑巧觉得,这项研究似乎比其他研究做得更好,当然这只是我的个人看法,要说我对这一想法的信念有多强烈,那根本还缺乏必要的证据支持。 But I feel like we are very far from the point where we know enough to be pushing people at risk of schizophrenia away from nicotine, and light-years away from the point where we can use phrases like “clear benefits”. 但是,我也认为,要说我们已经具备了足够的知识,以催促有精神分裂症患病风险的人远离尼古丁,那我们现在还差得远;要说使用“明显好处”一类的说法,那我们还差着很多光年。 Possibly I am an idiot and missing something very important. But if this is true, I wish the authors of the new study, and the editors of The Lancet, would have acknowledged the existence of the conflicting study and patiently explained to their readership, many of whom are idiots like myself, “Here’s a study that looks better than ours that seems to contradict our results, but here’s why our study is nevertheless far more believable.” That’s all I ask. 也许我是个笨蛋,忽略了一些非常重要的事情。但如果真是如此,我就希望上述新研究的作者们,以及《柳叶刀》的编辑们,能够承认与他们有相互冲突的研究存在,并能耐心地向读者们解释,因为许多读者跟我一样是笨蛋。“有项研究看起来比我们做得好,结论与我们的相反,但我们的研究仍然更可信,理由如下。”这才是我希望看到的。 No matter how much of an idiot I am, I can’t possibly imagine how that wouldn’t be a straight-out gain. 不管我有多么傻,我也根本无法想象,这么做怎么会不是一件彻头彻尾的好事。 PS: Cigarette smoking definitely decreases your risk of Parkinson’s Disease. Parkinson’s is similar to schizophrenia in that both involve dopamine. But schizophrenia involves too much dopamine and Parkinson’s too little, so the analogy could go either direction. 附:吸烟绝对会减少你患帕金森症的风险。帕金森症跟精神分裂症有些类似,两者都涉及到多巴胺。只是,精神分裂症是多巴胺过多,而帕金森症则是过少,所以该类比可以指向两个方向。【译注:即吸烟可能会减低,也可能会增加精神分裂症的风险。】 PPS: Tobacco smoking is definitely still bad! Nothing in here at all suggests that tobacco smoking has the slightest chance of not being a terrible decision! 又附:吸烟仍然绝对有害!本文没有任何地方说吸烟有可能不是个糟糕的决定,没门。 (编辑:辉格@whigzhou) *注:本译文未经原作者授权,本站对原文不持有也不主张任何权利,如果你恰好对原文拥有权益并希望我们移除相关内容,请私信联系,我们会立即作出响应。

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

【2016-07-25】

@whigzhou: 以统计学方法为主导的研究有个问题是,容易让人忽视一些有着根本重要性但又缺乏统计差异的因素,比如身高,在一个儿童营养条件普遍得到保障的社会,研究者可能会得出『营养不是影响身高的重要因素』的结论,并且这一结论可能在很多年中都经受住了考验,直到有一天,某一人群经历了一次严重营养不良……

@whigzhou: 在可控实验中,此类问题可以通过对营养条件这一参数施加干预而得以避免,但社会科学领域常常不具备对参数进行任意干预的条件,只能用统计学方法来模拟可控实验,可是(more...)

【2016-05-21】

@深大-子豪:辉总,冒昧问句,能否略微点评一下《无穷的开始:世界进步的本源》这本书?打扰了。

@whigzhou: 没读过,看了看介绍,感觉我不会有兴趣,这个人的念头听起来挺幼稚的

@whigzhou: 【不懂量子力学,我就随便嘀咕几句】1)多重世界,多么偷懒而幼稚的一张膏药啊,2)Deutsch对波普证伪主义的解读,好像还是很朴素的那种,3)同时推崇多重世界膏药和证伪主义,不觉得哪里有问题?4)有关模因已有了各种幼稚理论,Deutsch又添了一个,5)基因和模因居然能和多重世界扯上关系,惊了~

1)我把一些理论称为膏药,是因为我认为它们背离了可证伪性原则,

2)按我所采用的贝叶斯阐释,所谓可证伪性,就是能够就如何(结构性地)修正我们的(more...)

【2016-02-04】

@海德沙龙 《一个动听故事的破碎及永生》 诺奖得主Daniel Kahneman在《思考,快与慢》里讨论了一个有趣的发现,若考试时问题很难看清,得分会更高。这里的所谓考试,是由Shane Frederick发明的“认知反应测试”(CRT),Malcolm Gladwell觉得这个结论很爽,便将此事写进了《大卫与歌利亚》一书

@熊也餐厅: 不知道什么原因不太喜欢daniel kahneman~

@whigzhou: 呵呵说(more...)

A Trick For Higher SAT scores? Unfortunately no.

SAT高分有诀窍?很不幸,不是。

作者:Terry Burnham @ 2015-4-20

译者:沈沉(@你在何地-sxy)

校对:Drunkplane(@Drunkplane-zny)

来源:AEON, http://www.terryburnham.com/2015/04/a-trick-for-higher-sat-scores.html

Wouldn’t it be cool if there was a simple trick to score better on college entrance exams like the SAT and other tests?

如果SAT之类的大学入学考试和其他考试都有得高分的简单诀窍,岂不是很爽?

There is a reputable claim that such a trick exists. Unfortunately, the trick does not appear to be real.

根据某个著名说法,确实有诀窍。不幸的是,这一诀窍似乎并不可靠。

This is the story of an academic paper where I am a co-author with possible lessons for life both inside and outside the Academy.

这里要讲的是我参与写作的一篇学术论文的故事,它对学术内外的生活可能都会有些教益。

In the spring of 2012, I was reading Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman’s book, Thinking, Fast and Slow. Professor Kahneman discussed an intriguing finding that people score higher on a test if the questions are hard to read. The particular test used in the study is the CRT or cognitive reflection task invented by Shane Frederick of Yale. The CRT itself is interesting, but what Professor Kahneman wrote was amazing to me,

In the spring of 2012, I was reading Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman’s book, Thinking, Fast and Slow. Professor Kahneman discussed an intriguing finding that people score higher on a test if the questions are hard to read. The particular test used in the study is the CRT or cognitive reflection task invented by Shane Frederick of Yale. The CRT itself is interesting, but what Professor Kahneman wrote was amazing to me,

2012年春,我读了诺贝尔奖获得者Daniel Kahneman的书《思考,快与慢》。Kahneman教授讨论了一个非常有趣的发现,如果考试时的问题很难看清,人们得分就会更高。这一研究中用到的具体考试,是由耶鲁大学的Shane Frederick发明的“认知反应任务”(CRT)【译注:应为“认知反应测试”,原文有误】。CRT本身很有意思,但Kahneman教授的说法更是令我惊愕。

“90% of the students who saw the CRT in normal font made at least one mistake in the test, but the proportion dropped to 35% when the font was barely legible. You read this correctly: performance was better with the bad font.”

“通过正常字体阅读CRT试卷的测试学生中,有90%至少会做错一道题,但如果试卷字体勉强才能辨认,这个比例就会下降到35%。把这句话读准了:坏字体伴随着好成绩。”

I thought this was so cool. The idea is simple, powerful, and easy to grasp. An oyster makes a pearl by reacting to the irritation of a grain of sand. Body builders become huge by lifting more weight. Can we kick our brains into a higher gear, by making the problem harder?

我觉得这简直太爽了。这个想法简单、有力且容易掌握。蚌壳受沙粒刺激作出反应,就会生出珍珠。健身者加大举重重量就会增加块头。我们是否能通过把问题搞难,来加大大脑马力?

Malcolm Gladwell also thought the result was cool. Here is his description his book, David and Goliath:

Malcolm Gladwell also thought the result was cool. Here is his description his book, David and Goliath:

Malcolm Gladwell也觉得这个结论很爽。以下是他在《大卫与歌利亚》一书中的描述:

The CRT is really hard. But here’s the strange thing. Do you know the easiest way to raise people’s scores on the test? Make it just a little bit harder. The psychologists Adam Alter and Daniel Oppenheimer tried this a few years ago with a group of undergraduates at Princeton University. First they gave the CRT the normal way, and the students averaged 1.9 correct answers out of three. That’s pretty good, though it is well short of the 2.18 that MIT students averaged. Then Alter and Oppenheimer printed out the test questions in a font that was really hard to read … The average score this time around? 2.45. Suddenly, the students were doing much better than their counterparts at MIT.

“CRT真是很难。但这里有个怪事。要提高人们的考试得分,你知道什么方法最简单吗?只需把考题整得更难一点。心理学家Adam Alter和Daniel Oppenheimer几年前在普林斯顿大学拿一群本科生做过实验。首先他们用常规方式搞了一次CRT考试,学生平均表现是3道题里做对1.9道。很不错,但比起麻省理工学生平均做对2.18道可差远了。然后Alter和Oppenheimer用一种很难辨读的字体打印了测试问题……这次的平均得分?2.45。学生们突然就比麻省理工的对手要强了。”

As I read Professor Kahneman’s description, I looked at the clock and realized I was teaching a class in about an hour, and the class topic for the day was related to this study. I immediately created two versions of the CRT and had my students take the test – half with an easy to read presentation and half with a hard to read version.

As I read Professor Kahneman’s description, I looked at the clock and realized I was teaching a class in about an hour, and the class topic for the day was related to this study. I immediately created two versions of the CRT and had my students take the test – half with an easy to read presentation and half with a hard to read version.

读着Kahneman教授的上述描写时,我看了看表,发现还有约一个小时我就要去上课,课程当天的主题正与这一研究相关。我立即就制作了两种版本的CRT——一半易读、一半难(more...)

In the spring of 2012, I was reading Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman’s book, Thinking, Fast and Slow. Professor Kahneman discussed an intriguing finding that people score higher on a test if the questions are hard to read. The particular test used in the study is the CRT or cognitive reflection task invented by Shane Frederick of Yale. The CRT itself is interesting, but what Professor Kahneman wrote was amazing to me,

2012年春,我读了诺贝尔奖获得者Daniel Kahneman的书《思考,快与慢》。Kahneman教授讨论了一个非常有趣的发现,如果考试时的问题很难看清,人们得分就会更高。这一研究中用到的具体考试,是由耶鲁大学的Shane Frederick发明的“认知反应任务”(CRT)【译注:应为“认知反应测试”,原文有误】。CRT本身很有意思,但Kahneman教授的说法更是令我惊愕。

In the spring of 2012, I was reading Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman’s book, Thinking, Fast and Slow. Professor Kahneman discussed an intriguing finding that people score higher on a test if the questions are hard to read. The particular test used in the study is the CRT or cognitive reflection task invented by Shane Frederick of Yale. The CRT itself is interesting, but what Professor Kahneman wrote was amazing to me,

2012年春,我读了诺贝尔奖获得者Daniel Kahneman的书《思考,快与慢》。Kahneman教授讨论了一个非常有趣的发现,如果考试时的问题很难看清,人们得分就会更高。这一研究中用到的具体考试,是由耶鲁大学的Shane Frederick发明的“认知反应任务”(CRT)【译注:应为“认知反应测试”,原文有误】。CRT本身很有意思,但Kahneman教授的说法更是令我惊愕。

“90% of the students who saw the CRT in normal font made at least one mistake in the test, but the proportion dropped to 35% when the font was barely legible. You read this correctly: performance was better with the bad font.” “通过正常字体阅读CRT试卷的测试学生中,有90%至少会做错一道题,但如果试卷字体勉强才能辨认,这个比例就会下降到35%。把这句话读准了:坏字体伴随着好成绩。”I thought this was so cool. The idea is simple, powerful, and easy to grasp. An oyster makes a pearl by reacting to the irritation of a grain of sand. Body builders become huge by lifting more weight. Can we kick our brains into a higher gear, by making the problem harder? 我觉得这简直太爽了。这个想法简单、有力且容易掌握。蚌壳受沙粒刺激作出反应,就会生出珍珠。健身者加大举重重量就会增加块头。我们是否能通过把问题搞难,来加大大脑马力?

Malcolm Gladwell also thought the result was cool. Here is his description his book, David and Goliath:

Malcolm Gladwell也觉得这个结论很爽。以下是他在《大卫与歌利亚》一书中的描述:

Malcolm Gladwell also thought the result was cool. Here is his description his book, David and Goliath:

Malcolm Gladwell也觉得这个结论很爽。以下是他在《大卫与歌利亚》一书中的描述:

The CRT is really hard. But here’s the strange thing. Do you know the easiest way to raise people’s scores on the test? Make it just a little bit harder. The psychologists Adam Alter and Daniel Oppenheimer tried this a few years ago with a group of undergraduates at Princeton University. First they gave the CRT the normal way, and the students averaged 1.9 correct answers out of three. That’s pretty good, though it is well short of the 2.18 that MIT students averaged. Then Alter and Oppenheimer printed out the test questions in a font that was really hard to read … The average score this time around? 2.45. Suddenly, the students were doing much better than their counterparts at MIT. “CRT真是很难。但这里有个怪事。要提高人们的考试得分,你知道什么方法最简单吗?只需把考题整得更难一点。心理学家Adam Alter和Daniel Oppenheimer几年前在普林斯顿大学拿一群本科生做过实验。首先他们用常规方式搞了一次CRT考试,学生平均表现是3道题里做对1.9道。很不错,但比起麻省理工学生平均做对2.18道可差远了。然后Alter和Oppenheimer用一种很难辨读的字体打印了测试问题……这次的平均得分?2.45。学生们突然就比麻省理工的对手要强了。”

As I read Professor Kahneman’s description, I looked at the clock and realized I was teaching a class in about an hour, and the class topic for the day was related to this study. I immediately created two versions of the CRT and had my students take the test - half with an easy to read presentation and half with a hard to read version.

读着Kahneman教授的上述描写时,我看了看表,发现还有约一个小时我就要去上课,课程当天的主题正与这一研究相关。我立即就制作了两种版本的CRT——一半易读、一半难读,让我的学生去考。

As I read Professor Kahneman’s description, I looked at the clock and realized I was teaching a class in about an hour, and the class topic for the day was related to this study. I immediately created two versions of the CRT and had my students take the test - half with an easy to read presentation and half with a hard to read version.

读着Kahneman教授的上述描写时,我看了看表,发现还有约一个小时我就要去上课,课程当天的主题正与这一研究相关。我立即就制作了两种版本的CRT——一半易读、一半难读,让我的学生去考。

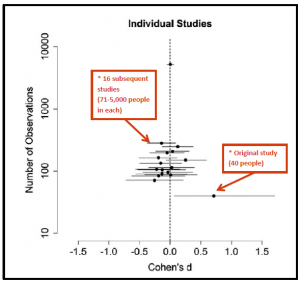

(1) A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat costs $1.00 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost? _____ cents (1) 球棒和球共需1.1美元。球棒比球要贵1美元。请问球需多少美分? (1) A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat costs $1.00 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost? _____ cents (in my experiment, I used Haettenschweiler - I do not know how to get blogger to display Haettenschweiler). (1) 球棒和球共需1.1美元。球棒比球要贵1美元。请问球需多少美分?(考试中,此处用的是Haettenschweiler字体)Within 3 hours of reading about the idea in Professor Kahneman’s book, I had my own data in the form of the scores from 20 students. Unlike the study described by Professor Kahneman, however, my students did not perform any better statistically with the hard-to-read version. I emailed Shane Frederick at Yale with my story and data, and he responded that he was doing further research on the topic. 在读过Kahneman教授书中的观点后不到三小时,我就拿到了自己的数据——20个学生的成绩。不过,跟Kahneman教授所述研究不同,统计上而言,我的学生在难读版测试中并没有表现更好。我把我的故事和数据邮寄给了耶鲁的Shane Frederic,他当时说他正在就此问题做进一步研究。 Roughly 3 years later, Andrew Meyer, Shane Frederick, and 8 other authors (including me) have published a paper that argues the hard-to-read presentation does not lead to higher performance. 大概三年以后,Andrew Meyer, Shane Frederick及其他8名作者(包括我)发表了一篇论文,论证说,难读的试题并不会带来更好的成绩。 The original paper reached its conclusions based on the test scores of 40 people. In our paper, we analyze a total of over 7,000 people by looking at the original study and 16 additional studies. Our summary: 最早那篇论文的结论来自40个人的测试得分。我们的论文则通过检视原初研究和其余16项研究,分析对象总数超过7000人。我们的总结是:

Easy-to-read average score: 1.43/3 (17 studies, 3,657 people) Hard-to-read average score: 1.42/3 (17 studies, 3,710 people) 易读版平均得分:1.43/3(17项研究,3657人) 难读版平均得分:1.42/3(17项研究,3710人)Malcolm Gladwell wrote, “Do you know the easiest way to raise people’s scores on the test? Make it just a little bit harder.” The data suggest that Malcolm Gladwell’s statement is false. Here is the key figure from our paper with my annotations in red: Malcolm Gladwell写道,“人们要想提高考试得分,你知道什么方法最简单吗?把考题整得更难一点。”数据显示,Malcolm Gladwell的说法是错的。以下是我们所写论文的关键图表,我的注解标红:

I take three lessons from this story.

从这个故事中我得到三条教训。

1.Beware simple stories.

1.提防简单的故事

“The price of metaphor is eternal vigilance.” Richard Lewontin attributes this quote to Arturo Rosenblueth and Norbert Wiener.

“比喻的好处须以永恒的警惕换取。”Richard Lewontin将这一名言归于Arturo Rosenblueth 和 Norbert Wiener所说。

The story told by Professor Kahneman and by Malcolm Gladwell is very good. In most cases, however, reality is messier than the summary story.

Kahneman教授和Malcolm Gladwell讲的故事非常动听。但在多数情况中,现实都比简洁的故事要凌乱。

2.Ideas have considerable “Meme-mentum”

2.观念具有相当大的“模因惯性”

“And yet it moves,” This quote is attributed to Galileo when forced to retract his statement that the earth moves around the sun.

“但是它仍在运转”,这一名言被认为是伽利略被迫收回其地球绕日运动学说时所说。

The message is that It takes a long time to change conventional wisdom. The earth stayed at the center of the universe for many people for decades and even centuries after Copernicus.

启示就是,要改变传统观点需要花费很长时间。在哥白尼之后的数十年甚至数世纪中,地球对许多人而言仍是宇宙的中心。

I take three lessons from this story.

从这个故事中我得到三条教训。

1.Beware simple stories.

1.提防简单的故事

“The price of metaphor is eternal vigilance.” Richard Lewontin attributes this quote to Arturo Rosenblueth and Norbert Wiener.

“比喻的好处须以永恒的警惕换取。”Richard Lewontin将这一名言归于Arturo Rosenblueth 和 Norbert Wiener所说。

The story told by Professor Kahneman and by Malcolm Gladwell is very good. In most cases, however, reality is messier than the summary story.

Kahneman教授和Malcolm Gladwell讲的故事非常动听。但在多数情况中,现实都比简洁的故事要凌乱。

2.Ideas have considerable “Meme-mentum”

2.观念具有相当大的“模因惯性”

“And yet it moves,” This quote is attributed to Galileo when forced to retract his statement that the earth moves around the sun.

“但是它仍在运转”,这一名言被认为是伽利略被迫收回其地球绕日运动学说时所说。

The message is that It takes a long time to change conventional wisdom. The earth stayed at the center of the universe for many people for decades and even centuries after Copernicus.

启示就是,要改变传统观点需要花费很长时间。在哥白尼之后的数十年甚至数世纪中,地球对许多人而言仍是宇宙的中心。

I expect that the false story as presented by Professor Kahneman and Malcolm Gladwell will persist for decades. Millions of people have read these false accounts. The message is simple, powerful, and important. Thus, even though the message is wrong, I expect it will have considerable momentum (or meme-mentum to paraphrase Richard Dawkins).

我预料,由Kahneman教授和Malcolm Gladwell所说的错误故事会继续存在几十年。数百万人读过这些错误说法。这个讯息简单、有力且重要无比。因此,尽管它是错的,我预测它会具有相当大的惯性动量(或借用Richard Dawkins的话说,模因惯性)。

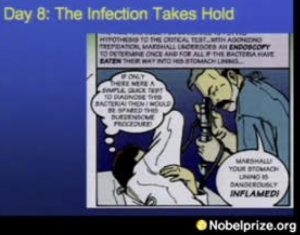

One of my favorite examples of meme-mentum concerns stomach ulcers. Barry Marshall and Robin Warren faced skepticism to their view that many stomach ulcers are caused by bacteria (Helicobacter pylori). Professor Marshall describes the scientific response to his idea as ridicule; in response he gave himself an ulcer drinking the bacteria. Marshall gives a personal account of his self-infection in his Nobel Prize acceptance video (the self-infection portion starts at around 25:00).

我最喜欢援引的模因惯性例证之一跟胃溃疡有关。Barry Marshall和Robin Warren认为许多胃溃疡源于细菌(幽门螺杆菌),这一观点遭到质疑。Marshall教授称,科学界的反应是认为他的观点十分可笑;作为回应,他服用细菌并让自己患上了溃疡。在其接受诺贝尔奖的视频中,Marshall自己描述了这一自我感染经历。

I expect that the false story as presented by Professor Kahneman and Malcolm Gladwell will persist for decades. Millions of people have read these false accounts. The message is simple, powerful, and important. Thus, even though the message is wrong, I expect it will have considerable momentum (or meme-mentum to paraphrase Richard Dawkins).

我预料,由Kahneman教授和Malcolm Gladwell所说的错误故事会继续存在几十年。数百万人读过这些错误说法。这个讯息简单、有力且重要无比。因此,尽管它是错的,我预测它会具有相当大的惯性动量(或借用Richard Dawkins的话说,模因惯性)。

One of my favorite examples of meme-mentum concerns stomach ulcers. Barry Marshall and Robin Warren faced skepticism to their view that many stomach ulcers are caused by bacteria (Helicobacter pylori). Professor Marshall describes the scientific response to his idea as ridicule; in response he gave himself an ulcer drinking the bacteria. Marshall gives a personal account of his self-infection in his Nobel Prize acceptance video (the self-infection portion starts at around 25:00).

我最喜欢援引的模因惯性例证之一跟胃溃疡有关。Barry Marshall和Robin Warren认为许多胃溃疡源于细菌(幽门螺杆菌),这一观点遭到质疑。Marshall教授称,科学界的反应是认为他的观点十分可笑;作为回应,他服用细菌并让自己患上了溃疡。在其接受诺贝尔奖的视频中,Marshall自己描述了这一自我感染经历。 3.We can measure the rate of learning.

3.我们可以测量学习的速率

We can measure the rate of learning. Google scholar counts the number of times a paper is cited by other papers. I believe that well-informed scholars who cite the original paper ought to cite the subsequent papers. We can watch in real-time to see if that is true.

我们可以测量学习的速率。“谷歌学术”计算某论文被其他论文征引的次数。我认为,渊博的学者,在引用了原初的研究论文之后,也应该引用其后相关的论文。我们能实时观测这一想法是否为真。

3.We can measure the rate of learning.

3.我们可以测量学习的速率

We can measure the rate of learning. Google scholar counts the number of times a paper is cited by other papers. I believe that well-informed scholars who cite the original paper ought to cite the subsequent papers. We can watch in real-time to see if that is true.

我们可以测量学习的速率。“谷歌学术”计算某论文被其他论文征引的次数。我认为,渊博的学者,在引用了原初的研究论文之后,也应该引用其后相关的论文。我们能实时观测这一想法是否为真。

| Paper 论文 | Comment 备注 | citations as of April 20, 2015 2015.4.20之前引用数 | citations as of today 迄今为止引用数 |

| Alter et al. (2007). "Overcoming intuition: metacognitive difficulty activates analytic reasoning." Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 136(4): 569. Alter等人(2007)。“克服直觉:元认知困难能激活分析推理”,《实验心理学杂志:总论》 136(4):569 | Original paper showing hard-to-read leads to higher scores 最早提出难读导致高分的论文 | 344 | click for current count 点击链接查看当前数字 |

| Thompson et al. (2013). "The role of answer fluency and perceptual fluency as metacognitive cues for initiating analytic thinking." Cognition 128(2): 237-251. Thompson等人(2013)。“回答流利性和感知流利性作为推动分析推理的元认知触发物”,《认知》 128(2):2237-251 | Paper contradicts Alter at. al by reporting no hard-to-read effect. 与Alter等人相左,报告不存在“难读高分”效应的论文 | 38 | click for current count 点击链接查看当前数字 |

| Meyer et al. (2015). "Disfluent fonts don’t help people solve math problems." Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 144(2): e16. Meyer等人(2015)。“繁难字体对于人们解决数学问题并无助益”,《实验心理学杂志:总论》 144(2): e16 | Our paper summarizing the original study and 16 others. 我们概述原初研究和后续16项研究的论文 | 0 (this “should” increase at least as fast as citations for Alter et. al, 2007) 0(引用数的增长速度“本应”至少与Alter等人2007年论文相同) | click for current count 点击链接查看当前数字 |

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

多年前我曾就中医发表过一些观点,今天不小心又提起这个话题,刚好这几年又有些新体会,再整理补充一下:

1)中医这个词的含义不太清楚,按较狭窄的用法,它是指一套理论体系(诸如阴阳五行、五脏六腑、气血经络、寒热干湿、温凉甘苦……),以及被组织在这套体系之内的各种治疗方法,而按较宽泛的用法,则囊括了所有存在于汉文化中的非现代医疗;

2)对于那套理论体系,我的态度是完全唾弃;

3)对于被归在中医名下的各种治疗方法,我的态度和对待其他前科学的朴素经验一样,持高度怀疑的态度;

4)但我不会像有些反中医者那样,做出一个强判断:它们(more...)

The Mythical conflict between science and Religion

科学与宗教间莫须有的冲突

作者:James Hannam @ 2009-10-17

译者:22(@ 22) 校对:白猫D(@白猫D)

来源:Medieval Science and Philosophy, http://jameshannam.com/conflict.htm

Introduction

简介

Newspaper articles thrive on cliché. These are not so much hackneyed phrases but rather the useful shorthand for nuggets of popular perception that allow the journalist to immediately tune his readers to the right wavelength. Yesterday’s clichés are, of course, today’s stereotypes as any perusal of earlier writing will show. The conflict between science and religion is an acceptable cliché that crops up all over the place.

报纸文章充斥着陈词滥调。这些陈词滥调倒不是简单的陈腐语句,而是一个流行见解百宝箱,让记者可以方便趁手地用来将读者调到正确的认知波段上。当然,阅读任何早期文字都将发现,正是昨日的陈词滥调成就了今日的刻板印象。科学与宗教之间的矛盾冲突,便是一个到处都普遍为人所接受的陈词滥调。

In the episode of The Simpsons in which the late Stephen J. Gould was a guest voice, Lisa found a fossil angel and events led to a court order being placed on religion to keep a safe distance from science. Articles in magazines and on the internet all assume that a state of conflict exists between science and religion, always has existed and that science has been winning.

比如在《辛普森一家》Stephen J. Gould客串配音的那一集中,Lisa发现了一具天使化石,这一事件导致法院判令宗教要与科学保持一定的安全距离。杂志、网络文章也都假定宗教和科学间的冲突是存在的,并将一直存在着,而科学总会是获胜的一方。

Most popular histories of science view all the evidence through this lens without ever stop(more...)

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

【2015-09-23】

@Ent_evo “用科学去塑造人,而不是让他们自然成长,这种想法让我们震惊……但这种想法当然是非理性的。……孩子所聆听的道德训诫,可能因为不科学而没有成效,但其意图也是塑造性格,就像赫胥黎笔下的耳语机器一样。因此,看起来我们并不反对塑造人,只要它很低效就行;我们反对的只是高效的塑造。”-罗素

@whigzhou: 罗素一谈社会就幼稚的一塌糊涂,也不想想,谁有资格塑造人?怎么算高效?目标不明怎么算效率?“用科学塑造人”又是什么意思?把(more...)

All Hail Science!

科学万岁!

作者:Jonah Goldberg @ 2015-2-14

译者:普罗米修斯(@普箩米修思),校对:Marcel ZHANG(@马赫塞勒张)

来源:National Review,http://www.nationalreview.com/article/398591/all-hail-science-jonah-goldberg

Memo to progressives: Unlike God, science doesn’t care if you believe in it.

进步主义者请记住:与上帝不同,科学并不在乎你是否信仰它。

Dear Reader (Unless you’re at the screening of Al-Qaeda Sniper),

亲爱的读者(除非你恰好在看《基地组织的狙击手》(Al-Qaeda Sniper)这部电影),

【译注:实际上不存在这部电影,那是一个叫“非裔美国人保守派”的博客虚构的,其副标题是“一个变性圣战者为使用‘无性别卫生间’的权利而抗争的故事”,显然是用来嘲讽目前在美国风起云涌的左翼平权运动的。】

All of us are equal in the eyes of God and the law — or at least that’s how it’s supposed to work. (Though the fact that Jon Corzine has neither been hit by lightning nor carted off to jail sometimes causes me moments of doubt on both fronts.)

无论在法律还是上帝面前,我们都是平等的——至少本该是这样。(尽管Jon Corzine既没遭雷劈也没被扔进监狱这一事实,让我时常对此感到疑惑)。

I try pay lip-service to the same principle about readers of this “news”letter, but let’s face it. That’s not true. Nearly all G-File readers are cherished, but not all are cherished equal.

我本想以此搪塞这封“新闻信”的读者:人人平等这项原则也适用于你们。不过我们还是直面现实吧,那并不是真的。我对几乎所有G-File的读者都很重视,但并非同等的重视。

(And, in a year or two when my next book comes out, the great schism in my heart will be between those of you who eagerly purchase my book, and you shameful free riders who, for years, were perfectly happy for me to throw you the gold Aztec idol week after week, but now refuse to throw me the whip as promised, saying “Adios, Señor.” This is the quid people, my next book will be the pro quo. If you assume each Goldberg File I’ve written is worth a quarter, you should probably convert it into zombie-apocalypse currency and assume it’s equal in value to a can of dog food, six dead D batteries, or a fully operational calk gun. But the price is what the market will bear, and even at that valuation, it would more than cover the price of my forthcoming magnum opus for any longtime reader. You have been put on notice.)

(并且,等一两年后我的新书出版时,我内心会在两类人之间撕扯:一类是那些迫不及待想要买书的读者,另一类则是那些可耻的搭便车者,多年来,他们满心欢喜地盼着我一周周地把阿兹特克金像(the gold Aztec idol)扔给他们,却不愿如之前说好的那样把鞭子给我扔过来,临走时只留下一句“再见,先生。”(“Adios, Señor.”西班牙语)。我的下一本书需要你用东西来交换的。如果你觉得我写的每一本G-File值得上一毛钱,或许你应该按僵尸界的汇率把它兑换成一罐狗粮、六个D号废旧电池或者一把铆钉枪。当然,书的价格应当是市场可以承受的,并且,对于我的长期读者,我即将出版的煌煌巨著应该是对得起它的标价的。我可是通知你们了哦。)【译注:这里有关阿兹特克金像和鞭子的哏出自电影《夺宝奇兵》。】

I bring this up because Charles Krauthammer is a reader of this “news”letter which, like seeing a spider monkey in your brand new kitchen making crème brûlée with a blowtorch, is both cool and scary. Why it’s cool should be obvious. He’s the Hammer. It’s scary because . . . he’s the Hammer.

我提这茬,是因为得知查尔斯·克劳萨默(Charles Krauthammer)也是这封“新闻信”的读者,这就像看见一只蜘蛛猴在你的崭新厨房里用喷灯做焦糖布丁,让人不知道该觉得有趣还是害怕。说他有趣的原因很明显,他是“锤子”,说他让人害怕是因为……他可是铁锤查理啊。【译注:注意Krauthammer中的hammer,意为锤子,铁锤查理(Charles Martel)则为查理大帝的祖父,法兰克王国实际掌权者,加洛林王朝奠基者,以武功著称的军事天才。】

I try very hard not to put a face to my readers because, frankly, this thing is sometimes so stupid and self-indulgent if I imagined a real person reading it, I’d push the keyboard away. It’s best if I write this thing like a message in a bottle going to no one.

我竭力在读者面前展示真实自我,因为装模作样会让我会显得任性而愚蠢,每当想到有人读到虚伪的自己,我就忍不住想要摔键盘。我最好是把这些话塞进漂流瓶,随浪漂走。最可能让我怯场的,就是想象查尔斯·克劳萨默是打开漂流瓶的那个人。

And the last thing I need for my performance anxiety is to imagine Charles Krauthammer is the guy unspooling my missive from that bottle. The only thing worse would be to imagine George Will standing behind Charles looking over his shoulder and tsk-tsking all of my split infinitives. And yet, to my dismay, Will, too, has told me he on occasio(more...)

Why does the Left get to pick which issues are the benchmarks for “science”? Why can’t the measure of being pro-science be the question of heritability of intelligence? Or the existence of fetal pain? Or the distribution of cognitive abilities among the sexes at the extreme right tail of the bell curve? 凭什么自由派有权来决定哪个问题是“科学”的测试基准?用智力可遗传性问题作为是否支持科学的标准不行吗?或者是否存在胎儿疼痛?或者两性认知能力在正态曲线远右端的分布情况? Or if that’s too upsetting, how about dividing the line between those who are pro- and anti-science along the lines of support for geoengineering? Or — coming soon — the role cosmic rays play in cloud formation? Why not make it about support for nuclear power? Or YuccaMountain? Why not deride the idiots who oppose genetically modified crops, even when they might prevent blindness in children? 或者,如果这些问题过于让人心烦,那么把是否支持地质工程作为支持科学与否的分界线如何?或者,宇宙射线在云的形成中的作用?是否支持核电可以吗?或者雅卡山(Yucca Mountain)?【译注:雅卡山位于内华达州,用来堆放核废料。】为什么不嘲讽下反对转基因作物的白痴呢,即使转基因作物(黄金大米)可以防止儿童失明? Some of these examples are controversial, others tendentious, but all are just as fair as the way the Left framed embryonic stem-cell research and all are more relevant than questions about evolution. (Quick: If Obama changed his mind about evolution tomorrow and became a creationist, what policies would change? I’ll wait.) 上述这些例子都是有争议或者倾向性的,左派支持的干细胞研究也是如此,而且跟进化论比起来,这些问题与实际生活关系密切。(打断下:如果明天奥巴马改变对进化论的态度而变成一个神创论者,哪些政策会变化呢?我得等等看才知道。) The point is that the Left considers itself the undisputed champion of “science,” but there are scads of issues where they take un-scientific points of view. 问题在于,左派一直自诩为“科学”斗士,但是在很多问题上,他们的持有的观点并不科学。 Sure they can cite dissident scientists — just as conservatives can — on this or that issue. But everyone knows that when the science directly threatens the Left’s pieties, it’s the science that must bend — or break. During the Larry Summers fiasco at Harvard, comments delivered in the classic spirit of open inquiry and debate cost Summers his job. Actual scientists got the vapors because he violated the principles not of science but of liberalism. 他们当然可以引用非主流科学家的意见为某个议题辩护,保守派也可以这么做。但是大家都懂的,每当科学直接威胁到左派的信条时,让步的却总是科学。劳伦斯·萨默斯(Larry Summers)在哈佛时,曾因敢于大胆地公开质询和辩论而丢了工作。真正的科学家因为违反了自由派的信条而非科学原则而被驱逐。 During the Gulf oil spill, the Obama administration dishonestly claimed that its independent experts supported a drilling moratorium. They emphatically did not. The president who campaigned on basing his policies on “sound science” ignored his own hand-picked experts. 在墨西哥湾漏油事件(the Gulf oil spill)中,奥巴马当局谎称其独立专家支持钻探禁令,但确凿无疑,这些专家并未这么说。虽然总统先生一直宣称自己的政策有坚实的科学基础,但他对身边的专家却置若罔闻。 According to the GAO, he did something very similar when he shut down Yucca Mountain. His support for wind and solar energy, as you suggest, isn’t based on science but on faith. And that faith has failed him dramatically. 根据美国政府问责局(GAO)的消息,类似的情况还有奥巴马关停了雅卡山一事。可以看出,他对风能和太阳能的大力扶植同样基于政治信条而非科学而这一信条让他一败涂地。 The idea that conservatives are anti-science is self-evident and self-pleasing liberal hogwash. I see no reason why conservatives should even argue the issue on their terms when it’s so clearly offered in bad faith in the first place. 认为保守主义者反科学的观点,毫无疑问是自由派们自我陶醉的一派胡言。我不明白保守派为什么非要在任期内就此问题与其争论,很明显这压根就是血口喷人嘛。Recently, others have made this point better than I have, but as the Marines say of their rifles, this “news”letter is mine. 最近也有其他人提出了类似的观点,而且表达得比我更好,但是——就像海军陆战队对自己的步枪敝帚自珍一样——这封“新闻信”毕竟是我自己的嘛。 Anyway, what I find really intriguing is the way people talk about “science” as if it is so much more — and occasionally less — than it is. Critics on Twitter and in my e-mail box say we need to know if Scott Walker “believes in science,” as if his answer on evolution will tell us if he’s a witch burner or not. 总之,我发现人们对科学的看法很有意思,他们似乎总是给科学赋予比事实上更多(有时候是更少)的含义,推特上和我邮箱中的一些批评意见,认为我们需要搞清楚斯科特·沃克是否真的“信仰科学”,似乎他的答案可以告诉我们他是否支持烧死女巫。 Well, I regularly get e-mail from creationists. E-mail. In other words, thanks to scientists, the words of creationists are transported through the sky into my phone or computer. And, while I haven’t checked, I’m pretty sure they don’t believe that their e-mail was carried to me on the backs of pixies. 我经常收到一些神创论者发来的电邮。是电子邮件哦。换句话说,幸亏有了科学家,这些神创论者的信息才得以穿越天空传到我的手机或者电脑中。尽管并未验证,但我很确定他们应当不会认为电邮是通过小精灵传给我的。 I’m also pretty sure that the vast majority of creationists drive cars, take antibiotics, watch TV, and eat foods with preservatives in them. For liberals, perhaps this is proof of some kind of hypocrisy or cognitive dissonance. And maybe it is, though I don’t see it. But it’s also a demonstration that having your faith — or your superstitions — bump into one of the farther borders of scientific knowledge doesn’t require one to reject all of science. 我也非常确信绝大多数神创论者开车、吃抗生素、看电视、食用含防腐剂的食品。自由派或许可以从中看出虚伪和认知失调的意味。也许是吧,但我没看出来。但对我来说,这一现象表明,你的信仰或迷信越出了科学知识的边界,并这不意味着你要摒弃科学这个整体。 It’s not a binary thing. Belief in something unconfirmed or even disproved by science is not a rejection of all science. Just as a refusal to believe unicorns are real doesn’t mean I have to reject the existence of the Loch Ness Monster, Bigfoot, Kate Upton, or other allegedly mythical creatures. 这并不是非此即彼的。对未经科学验证、甚至被科学所证伪的事物的信仰,并非是对科学整体的拒绝。仅仅不承认独角兽存在,并不意味着一个人会否认尼斯湖水怪、大脚怪、凯特·阿普顿(Kate Upton),或者其他传说中的神秘造物存在。 That’s part of the irony. The way the science-lovers talk about science, you’d think science was a kind of magic that requires total faith and conviction. If you don’t believe with all of your heart in “science,” it will stop working. It’s like the scientific enterprise is akin to Santa’s sleigh in the movie Elf (a great film, and not just because it inspired my daughter to answer the phone “Buddy the Elf, what’s your favorite color?”). 这真是讽刺啊,一些科学狂热分子眼中的科学让人感觉像是某种魔法,需要完全的信仰和信念。如果你不是全身心地信仰“科学”,它就不再起作用。这样的话,科技企业倒是跟电影《圣诞精灵》中圣诞老人的雪橇有些类似。(《圣诞精灵》是一部不错的电影,我这么认为,不仅仅是因为我女儿受到电影的影响,在接电话的时候会说“我是精灵巴迪,你最喜欢什么颜色?”)。 In Elf, Santa’s sleigh no longer relies on flying reindeer. Instead it converts“Christmas cheer” into jet power. That’s how some of these people talk about believing in science. If we don’t project our positive emotions towards it, it won’t take off. 在《圣诞精灵》中,圣诞老人的雪橇不是由会飞的驯鹿来牵引的,而是把“圣诞欢呼”转化成飞行动力。这和某些人口中的科学是一样的,如果我们不把正能量投射到圣诞雪橇上,它就不会起飞。 I am typing this on a plane from Detroit, Michigan — on Friday the 13th, no less. What happens if I suddenly stop saying in a hopeful whisper “I believe in you, science!” or if I take a deist bent and hold out the possibility that there’s something more than the material world out there? Will my plane suddenly plummet? Will gremlins slowly emerge from behind the seat in front of me, like Miley Cyrus climbing over a toilet-stall door? 今天是黑色星期五,我正在一架从密歇根州底特律市起飞的一架飞机上写这篇文章。现在,如果我不再满怀希望的嘀咕着“我信仰你,科学!”,或者开始相信自然神论的观点,认为很有可能在已知物质世界之外,还有其他存在,那么我的飞机会不会突然一头栽下去呢?会不会有一只小魔怪(gremlins,喜欢恶作剧)在我前面的椅背上浮现呢,就跟麦莉·赛勒斯从厕所隔间的门上爬过似的? Look, science, unlike God, really doesn’t care if you believe in it. And casting doubt on one part of it doesn’t break the spell. That’s the whole point of science; it’s not magic. 所以你看,科学跟上帝不同,根本不在乎你是否信仰它,对它某一个方面有质疑,并不会打破魔咒,这才是科学的真相,它不是魔法。【译注:《打破魔咒》也是哲学家丹尼尔·丹内特2006年的一部作品,副标题是“作为一种自然现象的宗教”,认为宗教信仰是一种曾经有用的虚假信念,可以帮助人们做到一些不然就做不到的事情,但在科学高度发展的今天,已经成为理性进步的障碍,是该打破它们的时候了。丹内特也是长期活跃在论战前线的无神论四骑士之一。】 Democrats are more likely to believe in paranormal activity. They’re also more likely to believe in reincarnation and astrology. I have personally known liberals who think crystals have healing powers who nonetheless believe that the internal combustion engine doesn’t actually rely on magical horse power. 民主党人更有可能相信超自然现象,他们也更有可能相信轮回和占星术。我私下认识一些自由派,他们相信水晶有治愈的功能,尽管如此,他们从不认为内燃机是依靠魔法的马力来运转的。 HELP ME, SCIENCE, YOU’RE MY ONLY HOPE 帮帮我吧,科学,你是我唯一的希望 But you wouldn’t necessarily know that from listening to these people freak out about it. (Sorry, this “news”letter will be light in links because there’s no internet on this plane. Fun fact: If you shout “There’s no Internet on this plane!” in a really loud, terror-filled, voice — as if the plane runs on Internet — your fellow passengers freak out. Try it some time. If it doesn’t work the first time, say it over and over. Eventually you’ll get a lot of attention.) 但是,你从受到惊吓的人口中未必能听到这句话。(实在抱歉,这封“新闻信”链接很少,这是因为飞机上没有因特网。说件趣事:假如你在飞机上用一种惊恐的语气大声喊:“这架飞机上居然没有互联网!”——就好像这架飞机是靠互联网飞行的——这会吓坏你周围的旅客。如果第一次不成功也没关系,再大声点多喊几次,最终大家都会注意到你的。) When I hear people talk about science as if it’s something to “believe in,” particularly people who reject all sorts of science-y things (vaccines, nuclear power, etc. as discussed above), I immediately think of one of my favorite lines from Eric Voegelin: “When God is invisible behind the world, the contents of the world will become new gods; when the symbols of transcendent religiosity are banned, new symbols develop from the inner-worldly language of science to take their place.” This will be true, he added, even when “the new apocalyptics insist that the symbols they create are scientific.” 很多人一谈起“科学”,就好像它应该是某种“信仰”,特别是那些拒绝所有听起来像科学的事物(维生素、核能等等)的人。每当听到这些,我就会想起埃里克·沃格林说过的,也是我最喜欢的一句名言:“当上帝从世界逐渐隐去,新的神灵又将崛起,当超验的宗教符号遭到禁止,科学的世俗语言将会取而代之”。这是事实,他补充道,“届时,新的先知把他们新创造的符号称作“科学”。 In other words, the “Don’t you believe in evolution!?!” people don’t really believe in science qua science, what they’re really after is dethroning God in favor of their own gods of the material world (though I suspect many don’t even realize why they’re so obsessed with this one facet of the disco ball called “science”). “Criticism of religion is the prerequisite of all criticisms,” quoth Karl Marx, who then proceeded to create his own secular religion. 换句话说,说“你居然不相信进化论?!”的人们,其实并不相信所谓的科学,他们的真实目的,是把原来的上帝赶下神坛,让位于他们在物质世界的新神(然而我怀疑他们并不清楚,为什么迪斯科球上让他们如此着迷的一个小侧面,会被称作“科学”)。“对宗教的批判是一切批判的前提”,卡尔·马克思如是说,但他转身创建了自己的世俗宗教。 This is nothing new of course. This tendency is one of the reasons why every time Moses turned his back on the Hebrews they started worshipping golden calves and whatnot. 当然,这种现象并不新奇。同时也解释了为何每次摩西一离开希伯来人,他们就开始崇拜诸如金牛犊之类的东西。 At least Auguste Comte, the French philosopher who coined the phrase “sociology,” was open about what he was really up to when he created his “Religion of Humanity,” in which scientists, statesmen, and engineers were elevated to Saints. As I say in my column, the fight over evolution is really a fight over the moral status of man. 与他们相比,奥古斯特·孔德至少是个敢想敢做的人,这位法国哲学家,“社会学”的创始人,创立了他的“人道教”,在那里,科学家、政治家和工程师是被当作圣人而崇拜的。正如我曾在我专栏中说过的,围绕进化论的论战其实是对人类当前道德状态的争论。 And, if we are nothing but a few bucks worth of chemicals connected by water and electricity, than there’s really nothing holding us back from elevating “science” to divine status and in turn anointing those who claim to be its champions as our priests. It’s no coincidence that Herbert Croly was literally — not figuratively, the way Joe Biden means literally — baptized into Comte’s Religion of Humanity 如果我们不过是一些通过水和电连接在一起的化学物质,那还有什么可以阻止我们把“科学”供上神坛,并为那些所谓科学斗士行涂油礼令、让他们做我们的神父呢。难怪赫伯特·克劳利会(货真价实地,不是象征性地,此处“货真价实”一词不是按乔·拜登那种用法)皈依孔德的人道教。【译注:乔·拜登曾在演讲中多次错误地使用“literally”一词,一度成为笑柄 】 Personally, I think the effort to overthrow Darwin along with Marx and Freud is misguided. I have friends invested in that project and I agree that all sorts of terrible Malthusian and materialist crap is bound up in Darwinism. But that’s an argument for ranking out the manure, not burning down the stable. 我个人认为,试图将达尔文和马克思与弗洛伊德绑在一起打倒是不对的。我有朋友正在这么做,并且我也同意,马尔萨斯主义者和唯物主义者的废话确实和达尔文主义的颇有渊源。但是,如果只是想清理掉马粪,何必把整个马厩也烧了呢? IN MEMORIAM 悼念 My brother Josh passed away four years ago this month. If I couldn’t get a G-File done this morning, I was going to recycle the one I wrote not long after his funeral. An excerpt: 我哥哥乔什是在四年前的这个月去世的。如果今早没写完G-File的话,本来打算把我在他葬礼后不久写的悼词重复利用的,以下是摘要: My brother died last week. He had an accident. He fell down some stairs. He surely had too much to drink when it happened. It’s all such an awful waste. You can read how I felt — how I feel — about my brother here. 家兄在上周辞世,那是场意外,他从楼梯上摔了下来,当时肯定喝了不少酒。这实在是有点浪费。点击这里的链接,你可以看到我曾经和现在对他去世的感受。 But, you know, this is uncharted territory for me. And while I have little to no morbid desire to wallow indefinitely in a public display of grieving, the G-File has always been a dispatch from the frontlines of my mind, a quasi-personal letter to the collective You. Some might even call it the mad scribbling in the virtual ink of diluted fecal matter on my imaginary jail-cell wall. 但是,你们也知道,这种情景对我非常陌生。而且我也实在不想在公开场合表现出一副沉浸在悲痛中无法自拔的样子。G-File一直占据着我的思维,它就像写给你们的一封私人信。也有人甚至说,这是我在自己想象的监牢中,把稀释粪便当作墨水进行的疯狂涂鸦。 And, as you can imagine, there are few things more on my mind than this choking fog of awfulness. 但是,如你们所想,现在占据我思维的,除了这难堪呛人的烟雾之外,又多了一些事情。 I’m told by a friend that there’s a new book out, The Truth about Grief by Ruth Davis Konigsberg, that apparently demonstrates how Elisabeth Kubler-Ross made up all that stuff about the “five stages of grief.” 一位朋友曾经对我说,最近出了本新书,是鲁思·戴维斯·柯尼斯堡写的《悲伤的真相》。这本书显然在试图说明伊丽莎白·库伯勒-罗斯是如何编造出“悲伤的五个阶段”这种破玩意儿的。 I have no plans to read it. But I’m fully prepared to believe that any hard-and-fast five-point definition of grief is bogus. Admittedly, my data sample set is pretty small but hugely significant; in the last six years I’ve lost my father and my brother out of a family of four people. And, already, it’s clear to me that the geography of grief cannot be so easily mapped. 我没想去读这本书,但是我认为所有对悲伤的严格的五点定义都是扯淡。说实话,我的统计样本相当小,但是结果非常显著:我们原本的四口之家,在过去的六年里,先后失去了父亲和兄弟。并且,我非常清楚悲伤的地图是很难被轻易描绘出来的。 Obviously there are going to be similarities to the terrain. But just as there are different kinds of happiness — say, winning the lottery versus having a kid, or beating cancer versus seeing Keith Olbermann booted off of MSNBC — there are different kinds of sadness, too. And how they play out depends on the context. 显然,不同人的悲伤“地形”或许有些许相似,但是正如幸福有许多种一样(比如,彩票中奖与喜得贵子、战胜癌症或基思·奥伯曼被MSNBC辞退一事),悲伤也有好多种。他们最终怎样消散取决于当时的具体情境。 In terms of my own internal response, the most glaring continuity between my dad’s death and my brother’s is loneliness. Don’t get me wrong. I’ve got lots of company. I have lots of people who care for me more than I realized. I’m richer in friends and family than I could ever possibly expect or deserve. 至于我个人的感受,父亲和兄弟的相继去世留给我的是无尽的孤独。请不要误会,我有很多人陪伴,我自己都没有意识到会有这么多人关心着自己。我所得到的友情和亲情已经远超自己的预期。 But there’s a kind of loneliness that comes with death that cannot be compensated for. Tolstoy’s famous line in Anna Karenina was half right. All unhappy families are unhappy in their own way, but so are all happy ones. At least insofar as all families are ultimately unique. 但是有一种孤独与死亡相伴而来,无法慰藉。托尔斯泰在《安娜·卡列妮娜》中的一句名言说对了一半,不幸的家庭各有各的不幸,幸福的家庭也是如此。至少每个家庭都是独特的。 Unique is a misunderstood word. Pedants like to say there’s no such thing as “very unique.” I don’t think that’s true. For instance, we say that each snowflake is unique. That’s true. No two snowflakes are alike. But that doesn’t mean that pretty much all snowflakes aren’t very similar. But, imagine if you found a snowflake that was ten feet in diameter and hot to the touch, I think it’d be fair to say it was very unique. Meanwhile, each normal snowflake has its own contours, its own one-in-a-billion-trillion characteristics, that will never be found again. 独特这个词被误解了,学究们经常说:没有真正“独一无二”的事物。我并不这么认为。比如,我们常说每一片雪花都是独特的,这是真的,没有两片完全一样的雪花。但是这并不意味着所有的雪花都不相似。假设你找到一片直径十英尺、摸起来烫手的雪花,我想说它很独特应该没问题吧。同时,每一片普通的雪花都有只属于它自己的轮廓,只属于它自己的万中无一的特征,在其它雪花上永远找不到的特征。 Families are similarly unique. Each has its own cultural contours and configurations. The uniqueness might be hard to discern from the outside and it certainly might seem trivial to the casual observer. Just as one platoon of Marines might look like another to a civilian or one business might seem indistinguishable from the one next door. But, we all know the reality is different. Every meaningful institution has a culture all its own. Every family has its inside jokes, its peculiar way of doing things, its habits and mores developed around a specific shared experience. 家庭和雪花一样有类似的独特性,每个家庭有它自己的文化形态和内涵。其独特性从外部难得一窥,况且外人也不会真正在意。正如对平民来说,一队海军陆战队员看起来都差不多,一间商铺和隔壁的也很难区分。但是我们都清楚,事实上是不同的。每一个实体机构都有其独特的文化。每个家庭都有它自己的内部笑话,它做事的原则,它基于自己某种共同经历的习惯和习俗。 One of the things that keeps slugging me in the face is the fact that the cultural memory of our little family has been dealt a terrible blow. Sure, my mom’s around, but sons have a different memory of family life than parents. And Josh’s recall for such things was always not only better than mine, but different than mine as well. I remembered things he’d forgotten and vice versa. In what seems like the blink of an eye, whole volumes of institutional memory have simply vanished. And that is a terribly lonely thought, that no amount of company and condolence can ease or erase. 我们这个小家庭的文化正在经历严重的打击,这让我心如刀割。当然了,母亲还在身边,但是子女跟父母对于家庭的记忆并不完全相同。而乔什对这些事情的回忆比我更清晰,并与我有所不同。我记得一些他已忘记的事情,反之亦然。仿佛眨眼之间,一些独有的记忆就这么消失了。每念及此,心中倍感孤独,即使再多陪伴也难以慰藉。 The pain is duller now, but the feelings are the same. 现在伤痛减轻了些,但感受没变。 (编辑:辉格@whigzhou) *注:本译文未经原作者授权,本站对原文不持有也不主张任何权利,如果你恰好对原文拥有权益并希望我们移除相关内容,请私信联系,我们会立即作出响应。

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

Physicists Should Stop Saying Silly Things about Philosophy

物理学家们,请别再对哲学说蠢话了

作者:Sean Carroll @ 2014-6-23

译者:Luis Rightcon(@Rightcon)

校对:斑马(@鹿兔马朦)、史祥莆(@史祥莆)、张三(@老子毫无动静的坐着像一段呆木头)

来源:Sean Carroll个人博客,http://www.preposterousuniverse.com/blog/2014/06/23/physicists-should-stop-saying-silly-things-about-philosophy/

The last few years have seen a number of prominent scientists step up to microphones and belittle the value of philosophy. Stephen Hawking, Lawrence Krauss, and Neil deGrasse Tyson are well-known examples.

过去几年,数位著名科学家跳出来贬低哲学的价值,其中广为人知的有Stephen Hawking,Lawrence Krauss和Neil de Grasse Tyson。

To redress the balance a bit, philosopher of physics Wayne Myrvold has asked some physicists to explain why talking to philosophers has actually been useful to them.

为了平衡一下这种偏见,一位物理学哲学家Wayne Myrvold请一些物理学家解释一下,为什么与哲学家沟通对他们自己的研究有所助益。

I was one of the respondents, and you can read my entry at the Rotman Institute blog. I was going to cross-post my response here, but instead let me try to say the same thing in different word(more...)

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——