【2016-04-01】

@whigzhou: 我评价历史小说/电影的指标之一,是对历史感的把握,在我看来,三流的历史感是一种同态谬论,总是将他试图表现的历史趋势、几种相互竞争的可能走向、关键转折点……之类,擅自植入当事人的自觉意识中,甚至通过他们的嘴巴喋喋不休的说出来,仿佛当事人个个都偷窥过上帝的账本,有着后见之明的便利,

@whigzhou: 二流作品要好一点,能够表现出历史洪流中当事者被浪涛推拉撕扯的无力感,但真正的好作品,既能表现个体的理(more...)

【2016-04-01】

@whigzhou: 我评价历史小说/电影的指标之一,是对历史感的把握,在我看来,三流的历史感是一种同态谬论,总是将他试图表现的历史趋势、几种相互竞争的可能走向、关键转折点……之类,擅自植入当事人的自觉意识中,甚至通过他们的嘴巴喋喋不休的说出来,仿佛当事人个个都偷窥过上帝的账本,有着后见之明的便利,

@whigzhou: 二流作品要好一点,能够表现出历史洪流中当事者被浪涛推拉撕扯的无力感,但真正的好作品,既能表现个体的理(more...)

Cereals, appropriability, and hierarchy

谷物、可收夺性和等级制

作者:Joram Mayshar, Omer Moav, Zvika Neeman, Luigi Pascali @2015-9-11

译者:Luis Rightcon(@Rightcon)

校对:沈沉(@你在何地-sxy)

来源:VoxEU,http://www.voxeu.org/article/neolithic-roots-economic-institutions

Conventional theory suggests that hierarchy and state institutions emerged due to increased productivity following the Neolithic transition to farming. This column argues that these social developments were a result of an increase in the ability of both robbers and the emergent elite to appropriate crops. Hierarchy and state institutions developed, therefore, only in regions where appropriable cereal crops had sufficient productivity advantage over non-appropriable roots and tubers.

传统理论认为,等级制和国家产生的缘由在于:人类在新石器时代农业转向时出现了生产率增长。而本专栏则指出,上述社会发展是掠夺者和新生的精英分子收夺谷物的能力上升的结果。因此,仅仅是在那些易于收夺的谷物比其他不易收夺的块根和块茎作物在产量上拥有充分优势的地区,才会产生等级制和国家。

What explains underdevelopment?

欠发达的原因是什么?

One of the most pressing problems of our age is the underdevelopment of countries in which government malfunction seems endemic. Many of these countries are located close to the Equato(more...)

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

Making Americans

造就美国人

作者:Will Morrisey @ 2015-11-25

译者:Veidt(@Veidt)

校对:沈沉(@你在何地-sxy)

来源:Online Library of Law and Liberty, http://www.libertylawsite.org/2015/11/25/making-americans/

English settlers in America might have intended to transmit the traditions of the mother country to subsequent generations. This didn’t exactly happen—partly because the settlers disagreed amongst themselves about which of those traditions deserved preservation, and partly because the experience of life in North America challenged many of the traditions they did want to preserve. The disagreement and the adaptation together led, eventually, to a political revolution.

来到美洲的殖民者们也许曾经试图让来自祖国的传统在他们的后代身上延续下去,但这最终未能实现——部分是因为这些殖民者无法就哪些传统值得被保留达成一致,部分是因为在北美的生活经历让许多他们曾希望保留的传统受到了挑战。他们的这些分歧和适应行为最终导致了一场政治革命。

Malcolm Gaskill puts it bluntly: “Migrants did have one thing in common: they were no longer in England, and they had to get used to it.”

Malcolm Gaskill直言不讳地写道:“这些移民的确有一个共同点:他们不再生活在英格兰了,而他们必须去适应这种新生活。”

His new book tracks what happened to the English in their three (very different) principal area(more...)

Whoever Commands the Ocean Commands the Trade of the World, and whoever Commands the Trade of the World Commands the Riches of the World, and whoever is Master of that Commands the World it self. 谁控制了海洋,谁就能控制全世界的贸易,而谁控制了全世界的贸易,也就控制了全世界的财富,而他也就成为了整个世界的主宰。Charles II resumed the strategy that had been set down decades earlier by the disgraced Francis Bacon, that of “merg[ing] politics, profit, and natural philosophy”—the conquest of nature for the relief of man’s estate, and particularly the British estate. 查理二世重新采用了由失势的弗朗西斯·培根【译注:培根于1621年被控贪污受贿,被判罚金和监禁,后来虽被豁免,但政治生涯却因此终结】在几十年前所定下的策略,也就是“将政治、利益和自然哲学合而为一”——通过征服自然来解放人的状况,特别是英国人的状况。 By now, about 60,000 English settlers lived in New England. Metacom, or “King Philip” of the Wampanoags, began a major war against them. “This was for the second generation what sea crossings and scratch-building had been for the first: a hardening, defining experience.” 此时已有大约6万名英国殖民者生活在新英格兰。Metacom,即万帕诺亚格部落的“菲利普王”发动了一场针对这些英国人的大规模战争。“对于第二代殖民者们来说,这场战争的意义就像是乘船渡海和白手起家对于第一代殖民者的意义一样:这是一次定义并强化他们身份的经历。” Using what we now call guerrilla tactics, the coalition of Indian tribes fought through the bitter winter of 1675-76, taunting their captives with the question, “Where is your God now?” Gaskill describes the “extravagant cruelty” of Indian and Englishman alike: “Indians tortured because martial ritual required it, the English to obtain intelligence.” 通过使用今天被称为游击战的战术,印第安部落联军在1675-76年的寒冬里奋勇作战,并讥讽他们的俘虏,问他们“现在你的上帝去哪儿了?”Gaskill在描述印第安人和英国人时都使用了“过分残忍”这个相同的字眼:“印第安人折磨俘虏,因为这是他们尚武仪式的要求,而英国人折磨俘虏则是为了获得情报。” Two thousand settlers died before the Indian coalition surrendered in July 1677. Sporadic Indian raids continued, and the colonists duly noted that their British brethren had offered no protective aid aside from parish collections, “which were mere gestures.” Nor did the British prove any more helpful in Maryland, where settlers put down a similar uprising. 在1677年7月印第安联军投降之前,有两千名殖民者死于这场战争。此后,印第安人零星的袭击仍在持续,而这些殖民者们也很好地意识到:他们的英国同胞除了搞一些教堂募捐之外,并没有为他们提供什么别的保护,“而这完全是一些象征性的帮助。”而在马里兰,英国人也并没有证明自己能够提供更多的帮助,那里的殖民者们也镇压了一场类似的印第安人起义。 By the third generation, writes Gaskill, “experience set the colonists apart, creating opposition internally and with England.” Struggles with Indians continued; in the north the tribes began to ally with the French, another Catholic enemy. Catholic James II ascended the throne in 1685, after Charles II died, intensifying the worries of Anglo-American Protestants. 到第三代殖民者的时候,“在北美不同地区的经历将这些殖民者们分隔开来,在他们内部和他们与英国之间造成了对立。”Gaskill写道。与印第安人的斗争仍在继续;在北部,印第安部落开始与英国殖民者的另一个天主教敌人法国结盟。信奉天主教的詹姆士二世于1685年查理二世死后登上英国王位,而这进一步加剧了盎格鲁-美利坚新教徒们的担忧。 West Indian and Virginian settlers added to their slave populations and simultaneously to their worries about slave rebellions. Along the Chesapeake, in the 1680s alone the slave population rose from 4,500 to 12,000. This increase also decreased incidences of manumission; a people engaged in demographically-based dominance of the Indians had no intention of being overwhelmed by emancipated African slaves. 西印度群岛和弗吉尼亚的殖民者增加了他们的奴隶数量,而这也同时加剧了他们对奴隶叛乱的担忧。在切萨皮克湾沿岸,仅仅在1680年代奴隶数量就从4500人上升到了12000人。而这种数量增加也降低了奴隶解放运动事件的几率;一群忙于在人口数量上对印第安人形成优势的殖民者绝不希望自己在数量上被那些被解放的非洲奴隶们超过。 No solution—even in theory—to any of these ethno-political or religio-political dilemmas was available to Americans until a writer of the time, John Locke, began publishing. A political regime founded upon the principle of equal natural rights could form the basis of racial and religious peace in a political community that actually framed laws to conform to that principle. 即使从理论上说,当时也没有任何办法能够帮助美国人解决这些民族政治和宗教政治难题,直到那个时代的一位作家开始著书立说,他就是约翰·洛克。如果一个政治共同体的法律确实能遵从平等的自然权利原则,那么它那建立在此原则之上的政权就能够为种族间和宗教间的和平提供基础。 Gaskill mentions Locke in passing but mistakes his natural rights philosophy for “pragmatism.” What made the third generation of Americans react against the excesses of the last witch-hunting spasm, in 1690s Salem, was not pragmatism but an understanding of Christianity that Americans in New England were the first to begin to integrate into their laws. Gaskill在书中顺带提到了洛克,但却将他的自然权利哲学误认为是“实用主义”。面对1790年代塞勒姆掀起的最后一场追捕女巫的过分风潮,第三代美国人奋起反对,而促使他们这么做的并不是什么“实用主义”,而是基于对基督教义的理解,新英格兰的美国人也率先将这种理解整合到了他们的法律中。 Writes Gaskill: “Boston’s Brattle Street Church was founded in 1698 not upon scriptural literalism, the ‘New England way,’ or a covenant, but upon nature, reason, and inclusiveness”—in other words, upon a combination of Christianity and Lockean philosophy. What remained of the older generations, he concludes, was a legacy of “extraordinary courage.” Gaskill写道:“波士顿Brattle街教堂建立于1698年,它的建立并非基于‘新英格兰式’的圣经字面主义,或基于一个宗教誓约,它的基础是自然、理性与包容。”——换句话说,它建立在基督教和洛克哲学的结合之上。他总结道,老一代人为新的殖民者们所留下的遗产仅仅是他们“非凡的勇气”。 The commercial republic of the future would prove battle-ready, to the dismay of its enemies for centuries to come. 这个未来的商业共和国将会证明它已经做好了战斗的准备,而这将让它此后数个世纪的敌人们都感到沮丧。 (编辑:辉格@whigzhou) *注:本译文未经原作者授权,本站对原文不持有也不主张任何权利,如果你恰好对原文拥有权益并希望我们移除相关内容,请私信联系,我们会立即作出响应。

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

Tom Holland: We must not deny the religious roots of Islamic State

Tom Holland: 我们不能否认伊斯兰国的宗教根基

作者:Tom Holland @ 2015-3-17

译者:Horace Rae

校对:沈沉(@你在何地-sxy)

来源:News Statesman,http://www.newstatesman.com/politics/2015/03/tom-holland-we-must-not-deny-relgious-roots-islamic-state

Its jihadis call for a global caliphate. So why deny religion drives Isis?

伊斯兰圣战者呼吁建立一个全球哈里发帝国。所以,我们何以否认伊斯兰国乃由宗教所驱动?

in 1545, a general council of the Western Church was convened by Pope Paul III in the Tyrolean city of Trent. The ambition of the (more...)

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

犹太人为何那么聪明

——两种选择力量如何塑造少数族群的独特禀赋

辉格

2016年2月27日

“犹太人特别聪明”——这恐怕是最难反驳的一句种族主义言论了。

自诺贝尔奖设立以来,犹太人共拿走了19%的化学奖、26%的物理奖、28%的生理与医学奖、41%的经济学奖;在其它顶级科学奖项中,这个比例甚至更高,综合类:38%的美国国家科学奖、25%的京都奖,数学:25%的菲尔兹奖、38%的沃尔夫奖,信息科学:25%的图灵奖、37%的香农奖、42%的诺依曼奖;在非科学领域,犹太人还拿走13%的诺贝尔文学奖,1/3以上的普利策奖,1/3以上的奥斯卡奖,近1/3的国际象棋冠军。

犹太人在科学和艺术上的成就着实令人惊叹,他们以世界千分之二的人口,在几乎所有科学领域都拥有1/5到1/3的顶级学者;究竟是什么原因让他们取得了如此惊人的成就?

考虑犹太民族的独特性,就难免想到他们在大流散(The Diaspora)之后所面临的特殊文化处境;丧失故国、散居各地的犹太人,无论最初在罗马帝国境内,还是后来在西方基督教世界和东方伊斯兰世界,皆处于少数族地位,而且因为拒绝改宗,长期被排斥在主流社会之外,不仅文化上受歧视,法律上也被剥夺了许多权利,屡屡遭受迫害、驱逐、甚至屠杀。

在中世纪欧洲,经济活动、财产权利和法律地位都与宗教有着难分难解的关系,作为异教徒,犹太人不可能与基督徒君主建立领主-附庸关系从而承租土地,无法组织手工业行会(因为行会也须以附庸身份向领主获取特许状),也无法与贵族通婚以提升社会地位,甚至无法由教会法庭来保障自己的遗嘱得到执行……总之,作为封建体系之基础的封建契约关系和教会法,皆与之无缘。

这样一来,他们就被排斥在几乎所有重要的经济部门之外,留给他们的只有少数被封建关系所遗漏的边缘行业,比如教会禁止基督徒从事(或至少道德上加以贬责)的放贷业,替贵族征收租税的包税/包租人,与放贷和收租有关的私人理财业,以及少数未被行会垄断的商业。

这些行当的共同特点是:缺乏垄断权保护因而极富竞争性,需要一颗精明的头脑,读写和计算能力很重要;这些特点提示了,犹太父母可能更愿意投资于孩子的教育,提升其读写计算能力,以及一般意义上运用理性解决问题的能力。

这一投资策略迥异于传统社会的主流策略,在传统农业社会,人们为改善家族长期状况而进行的投资与积累活动,主要集中于土地、上层姻亲关系、社会地位和政治权力,但犹太人没有机会这么做,因而只能集中投资于人力资本,而且在随时有着被没收和驱逐风险的情况下,投资人力资本大概也是最安全的。

正如一些学者指出,按古代标准,犹太人确实有着良好的教育传统,比如其宗教传统要求每位父亲都应向儿子传授妥拉(Torah)和塔木德(Talmud)等经典,在识字率很低的古代,仅从经文学习中获得的基本读写能力也相当有价值。

然而这一解释有个问题,假如犹太人的智力优势仅仅来自其教育和文化传统,那就无法说明,为何近代以来,当这一文化差异已不复存在(或不再重要),他们的智力优势却依然显著?实际上,现代杰出犹太科学家的教育和成长经历中,犹太背景已无多大影响,甚至犹太认同本身也已十分淡薄了。

为解开犹太智力之谜,犹他大学的两位学者格里高列·科克伦(Gregory Cochran)和亨利·哈本丁(Henry Harpending)在2005年的一篇论文中提出了一个颇为惊人的观点:犹太智力优势是近一千多年中犹太民族在严酷选择压力之下的进化结果,因而有着可遗传的生物学基础;在2009年出版的《万年大爆炸》(The 10,000 Year Explosion)一书中,他们专门用一章介绍了这一理论。

他们认为,犹太人中表现出显著智力优势的,是其中被称为阿什肯纳兹人(Ashkenazi)的一个分支,其祖先是9-11世纪间陆续从南欧和中东翻越阿尔卑斯山进入中欧的犹太移民,和留在地中海世界的族人相比,他们遭受的排挤和限制更加严厉,职业选择更狭窄,而由于前面所说的原因,这些限制对族群的智力水平构成了强大的选择压力。

如此特殊的社会处境,使得聪明好学、头脑精明的个体有着高得多的机会生存下去,并留下更多后代,经过近千年三四十代的高强度选择,与高智商有关的遗传特性在种群中的频率显著提高;据乔恩·昂蒂纳(Jon Entine)和查尔斯·穆瑞(Charles Murray)等学者综合多种来源的数据估算,阿什肯纳兹人的平均智商约110(科克伦的估算值更高,为112-115),比美国同期平(more...)

【图1】若干精英度偏高的美国少数族群在医生中的相对代表率

上图列出了在医生职业中的相对代表率高于1的16个少数族群,其中有些可能出乎许多人的意料,高居榜首的埃及科普特基督徒尤为惹眼,科普特人血缘上属于埃及土著,在罗马帝国后期皈依了基督教,并且直到阿拉伯征服之前,始终构成埃及人口的多数,在罗马和拜占庭帝国统治下,科普特人长期处于社会底层,与“精英”二字完全无缘,正是在阿拉伯人统治下,前述选择机制将它从一个底层多数群体改造成了少数精英族群。

然后,向美国的移民过程又发生了二次筛选,科普特人尽管在埃及有着较高精英度,但相对于发达国家仍是贫穷者,只有其中条件最优越、禀赋最优秀者,才能跨越移民门槛而进入美国,可以说,他们是精英中的精英。

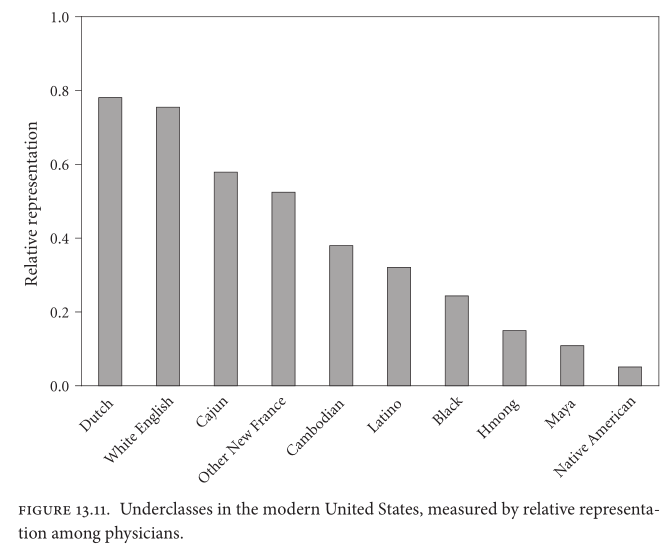

但不是所有移民群体都有着较高的精英化程度,如下图所示,拉美人、柬埔寨人、赫蒙人([[Hmong]],即越南苗族),在医生中的代表率皆远低于基准水平。

【图1】若干精英度偏高的美国少数族群在医生中的相对代表率

上图列出了在医生职业中的相对代表率高于1的16个少数族群,其中有些可能出乎许多人的意料,高居榜首的埃及科普特基督徒尤为惹眼,科普特人血缘上属于埃及土著,在罗马帝国后期皈依了基督教,并且直到阿拉伯征服之前,始终构成埃及人口的多数,在罗马和拜占庭帝国统治下,科普特人长期处于社会底层,与“精英”二字完全无缘,正是在阿拉伯人统治下,前述选择机制将它从一个底层多数群体改造成了少数精英族群。

然后,向美国的移民过程又发生了二次筛选,科普特人尽管在埃及有着较高精英度,但相对于发达国家仍是贫穷者,只有其中条件最优越、禀赋最优秀者,才能跨越移民门槛而进入美国,可以说,他们是精英中的精英。

但不是所有移民群体都有着较高的精英化程度,如下图所示,拉美人、柬埔寨人、赫蒙人([[Hmong]],即越南苗族),在医生中的代表率皆远低于基准水平。

【图2】若干精英度偏低的美国族群在医生中的相对代表率

比较两组族群不难看出,造成这一差别的关键在于移民机会从何而来,不同性质的移民通道有着不同的选择偏向;拉丁裔移民大多利用靠近美国的地理优势,从陆地或海上穿越国境而来,柬埔寨人和赫蒙人则大多是1970年代的战争难民,这两类移民通道,对移民的个人禀赋都不构成正向选择;相比之下,其他移民通道——上大学、工作签证、投资移民、政治避难、杰出人士签证,都有着强烈的选择偏向。

观察这一差别的最佳案例是非洲裔美国人,在上面两张图表中都有他们的身影,图2中的黑人是指其祖先在南北战争前便已生活在美国的黑人,他们在医生中的代表率仅高于美洲原住民,图1中的非洲黑人是指南北战争后来自撒哈拉以南非洲的黑人移民,医生代表率4倍于基准水平,5倍于德裔和英裔美国人。

这一差别显然源自不同移民通道的选择偏向,老黑人的祖先是被贩奴船运到美洲的,而新黑人的祖先则是凭借自身优势或个人努力来到美国,往往来自母国的精英阶层,奥巴马便属于后一类,他来自肯尼亚的一个富裕家族,其曾祖父娶了5位妻子,祖父曾为英国军队服役,精通英语和读写,娶了至少3位妻子,父亲6岁便进入教会学校,后来又在夏威夷大学和哈佛大学取得学位,回国后先后在肯尼亚交通部和财政部担任经济学家,虽然只活了46岁,却娶过4位妻子,生了8个孩子。

【图2】若干精英度偏低的美国族群在医生中的相对代表率

比较两组族群不难看出,造成这一差别的关键在于移民机会从何而来,不同性质的移民通道有着不同的选择偏向;拉丁裔移民大多利用靠近美国的地理优势,从陆地或海上穿越国境而来,柬埔寨人和赫蒙人则大多是1970年代的战争难民,这两类移民通道,对移民的个人禀赋都不构成正向选择;相比之下,其他移民通道——上大学、工作签证、投资移民、政治避难、杰出人士签证,都有着强烈的选择偏向。

观察这一差别的最佳案例是非洲裔美国人,在上面两张图表中都有他们的身影,图2中的黑人是指其祖先在南北战争前便已生活在美国的黑人,他们在医生中的代表率仅高于美洲原住民,图1中的非洲黑人是指南北战争后来自撒哈拉以南非洲的黑人移民,医生代表率4倍于基准水平,5倍于德裔和英裔美国人。

这一差别显然源自不同移民通道的选择偏向,老黑人的祖先是被贩奴船运到美洲的,而新黑人的祖先则是凭借自身优势或个人努力来到美国,往往来自母国的精英阶层,奥巴马便属于后一类,他来自肯尼亚的一个富裕家族,其曾祖父娶了5位妻子,祖父曾为英国军队服役,精通英语和读写,娶了至少3位妻子,父亲6岁便进入教会学校,后来又在夏威夷大学和哈佛大学取得学位,回国后先后在肯尼亚交通部和财政部担任经济学家,虽然只活了46岁,却娶过4位妻子,生了8个孩子。

America’s first fisherman bagged Alaskan salmon 11,500 years ago

11500年前,阿拉斯加渔民的鲑鱼

作者:Zach Zorich @ 2015-9-21

译者:沈沉(@你在何地-sxy)

校对:龟海海

来源:AAAS,http://news.sciencemag.org/plants-animals/2015/09/america-s-first-fisherman-bagged-alaskan-salmon-11500-years-ago

If you think most fish stinks after 3 days, try 11,500 years: That’s the age of salmon bones that archaeologists have uncovered at the Upward Sun River site, one of Alaska’s oldest human settlements.

如果你觉得大部分鱼放三天就会发臭,试试放11500年,考古学家在在向阳河遗址中发掘出的鲑鱼骨头就有这么古老,那里是阿拉斯加最早的人类聚居点之一。

They say the cooked bones provide the first clear evidence of salmon fishing among the earliest Americans, Paleoindians, who crossed from Siberia into Alaska ov(more...)

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

I love the Victorian era. So I decided to live in it.

我热爱维多利亚时代,所以决定生活于其中。

作者:Sarah A. Chrisman @ 2015-9-09

译者:沈沉(@你在何地-sxy)

校对:龟海海

来源:Vox,http://www.vox.com/2015/9/9/9275611/victorian-era-life

My husband and I study history, specifically the late Victorian era of the 1880s and ’90s. Our methods are quite different from those of academics. Everything in our daily life is connected to our period of study, from the technologies we use to the ways we interact with the world.

我丈夫和我都研究历史,具体说是维多利亚时代晚期,即1880至1890年代。我们跟学院派的方法极为不同。我们日常生活中的所有事物,从我们所用的技术到我们与世界沟通的方式,都跟我们所研究的时代有关联。

Five years ago we bought a house built in 1888 in Port Townsend, Washington State — a town that prides itself on being a Victorian seaport. When we moved in, there was an electric fridge in the kitchen: We sold that as soon as we could. Now we have a period-appropriate icebox that we stock with block ice. Every evening, and sometimes twice a day during summer, I empty th(more...)

******

The process didn't happen all at once. It's not as though someone suddenly dropped us into a ready-furnished Victorian existence one day— that sort of thing only happens in fairy tales and Hollywood. We had to work hard for our dreams. The life we now enjoy came bit by bit, through gifts we gave each other. The greatest gift we give each other is mutual support in moving forward with our dreams. 这一转变并非一蹴而就。并不是说某人某天突然就将我们拉入了一个配备齐全的维多利亚式生活——这种事只会发生于童话故事或好莱坞中。我们得为我们的梦想辛苦奔忙。我们现在所享受的生活是通过我们送给彼此的礼物而一点一点得来的。我们所赠与彼此的最美好礼物就是伴着梦想相濡以沫的走下去。 Even before I met Gabriel, we both saw value in older ways of looking at the world. He had been homeschooled as a child, and he never espoused the strict segregation that now seems to exist between life and learning. As adults, we both wanted to learn more about a time that fascinated each of us. But it took mutual support to challenge society's dogmas of how we should live, how we should learn. We came into it gradually — and together. 早在我与Gabriel相识之前,我们就都已看到了老式世界观的价值所在。他小时候接受过家庭式教育,从不赞成生活与学习之间如今看似存在的那种严格分离。长大以后,我们都渴望更多地了解那个让我们都无比着迷的时代。但要挑战社会关于我们应该如何生活、应该如何学习的成见,这需要共同渡过。我们是逐渐——也是共同——步入这一点的。 It's hard to say who started it. I was the first to start wearing Victorian clothes, but Gabriel, who knew how I'd always admired Victorian ideals and aesthetics, gave them to me as presents, a way for both of us to research a culture we found fascinating. I was so intrigued by those clothes that I hand-sewed copies I could wear every day. 很难说我们之间是谁最先开始这么做的。其实是始于我穿维多利亚式的服装,不过Gabriel知道我素来崇尚维多利亚式的理念和审美,是他把那些服饰送给我作礼物的,这也是我们研究这种令我俩都着迷的文化的一种方式。我被这些衣物深深地迷住,以至于我手缝了许多件类似的,可以每日做伴。 Soon after, I gave Gabriel an antique suit of his own, but tailoring men's clothes is a separate skill set, and it took him a while to find a seamstress who could make Victorian men's clothing with the same painstaking attention to historic detail that I was putting into my own garments. 随后不久,我又送了Gabriel一套古董西装,不过缝制男士服装需要另一种技能,所以他花了段时间才找到一位女裁缝。这位裁缝能为他缝制维多利亚式的男装,并像我对待我的衣物一样,为其历史细节煞费苦心。 Wearing 19th-century clothes on a daily basis gave us insights into intimate life of the past, things so private and yet so commonplace they were never written down. Features of posture, movement, balance; things as subtle as the way my ankle-length skirts started to act like a cat's whiskers when I wore them every single day. 在日常生活中穿着19世纪的服装,为我们提供了有关过往私密生活的洞见,这类事物如此隐私却又如此日常,以至于从未被人书写过。姿势、动作与平衡的特征;一些无比微妙的事物,比如当我每天都穿着及踝长裙时,它们开始像猫须一样飘逸。 I became so accustomed to the presence and movements of my skirts, they started to send me little signals about my proximity to the objects around myself, and about the winds that rustled their fabric — even the faint wind caused by the passage of a person or animal close by. 对于裙子的存在和运动,我变得无比熟稔,以至于当我接近身边的事物时,当风与布面摩擦作响时——即便是临近的人或动物穿过时导致的那种微弱的风,它们都会给我传递小小的信号。 I never had to analyze these signals, and after a while I stopped even thinking about them much; they became a peripheral sense, a natural part of myself. Gabriel said watching me grow accustomed to Victorian clothes was like seeing me blossom into my true self. 我从不需要去分析这些信号,而且一段时间以后技艺已熟练于心;它们成为了一种外围感官,我自己的自然的一部分。Gabriel曾说,看着我逐渐适应维多利亚式衣服,就像是看到我那个绽放的真实自我。 When we realized how much we were learning just from the clothes, we started wondering what other everyday items could teach us. 当我们意识到仅仅从衣服上我们学到的就何其之多时,我们开始琢磨其它的日常用品能够教给我们什么。 When cheap modern things in our lives inevitably broke, we replaced them with sturdy historic equivalents instead of more disposable modern trash. Every birthday and anniversary became an excuse to hunt down physical artifacts from our favorite time period, which we could then study and use together. 当我们生活中便宜的现代物品不可避免地破损时,我们就代之以结实耐用的历史对应物,而不再用那种不能重复使用的现代垃圾。每个生日和纪念日都变成了搜罗我们最钟爱时代的人工制品的理由,然后它们就可以供我们一起研究和使用。 Everything escalated organically from there, and now our whole life revolves around this ongoing research project. No one pays us for it, but we take it more seriously than many people take their paying jobs. 一切都从那里开始有机的成长了起来,如今我们整个生活都围绕着这个持续进行的研究项目打转。没人为此向我们提供资金,但我们对待它,可比许多人对待他们的有偿工作更为严肃。******

The artifacts in our home represent what historians call "primary source materials," items directly from the period of study. Anything can be a primary source, although the term usually refers to texts. The books and magazines the Victorians themselves wrote and read constitute the vast bulk of our reading materials — and since reading is our favorite pastime, they fill a large percentage of our days. 我们家中的人工制品代表的是历史学家所谓“一手材料”,都是直接来自所研究时代的物品。任何事物都可以是一手的,尽管这个词汇通常指涉文本。维多利亚时代的人们自身所写作和阅读的书籍和杂志构成了我们的阅读材料的主要部分——并且由于阅读是我们最爱的消遣,它们也占据了我们一天中的很大一部分时间。 There is a universe of difference between a book or magazine article about the Victorian era and one actually written in the period. Modern commentaries on the past can get appallingly like the game "telephone": One person misinterprets something, the next exaggerates it, a third twists it to serve an agenda, and so on. Going back to the original sources is the only way to learn the truth. 关于维多利亚时代的书籍或杂志,和写于这一时期的书籍或杂志,两者之间有着天壤之别。对于过往的现代评论有可能像“打电话”游戏一样令人吃惊:某人曲解了某事,另一人进一步夸大,第三个人出于某个目的对其加以扭曲,如此持续。回顾原始材料是了解真相的唯一办法。 We're devoted to getting our own insights and perspectives on the era, not just parroting stereotypes that "everyone knows." The late Victorian era was an incredibly dynamic time, with so many new and extraordinary inventions it seemed anything was possible. 我们矢志于获得我们自己对这一时代的见解和观点,而不是仅仅人云亦云“众所周知”的刻板印象。晚期维多利亚时代是个充满活力的时期,有许多全新而非凡的发明,看起来似乎无所不能。 Interacting with tangible items from that time helps us connect with and share that optimism. They help us understand the culture that created them — a culture that believed in engineering durable, beautiful items that could be repaired by their users. 与源于这一时期的实物接触,能帮助我们了解并分享这种乐观主义。它们有助于我们理解那一创造了它们的文化——一种对制造耐用、美观且能由使用者修理的物品存有信念的文化。 Constantly using them helps us comprehend their context. Absorbing the lessons our artifacts teach us shapes our worldview. They are our teachers. Seeing their beauty every day elevates and inspires us, as it did their original owners. 在不断使用它们的过程中,我们领悟其内涵。吸收由我们的物品教给我们的教训,也塑造了我们的世界观。它们是我们的老师。欣赏它们的美,也提升并鼓舞了我们,就像它们曾提升鼓舞了其最初的主人一样。 It's a life that keeps us far more in touch with the natural seasons, too. Much of modern technology has become a collection of magic black boxes: Push a button and light happens, push another button and heat happens, and so on. The systems that dominate people's lives have become so opaque that few Americans have even the foggiest notion what makes most of the items they touch every day work — and trying to repair them would nullify the warranty. 这也让我们能无比贴近天然的四季轮替。多数现代技术都已然变成了一堆魔法黑箱子:按这个按钮就有光,按另一个按钮就有热,如此等等。主导人们生活的种种系统已变得如此晦涩,以至极少有美国人对他们每天碰到的物品都是如何运作的具有哪怕是模糊的概念——试着去修理它们还会使质保单作废。 The resources that went into making those items are treated as nothing more than a price tag to grumble about when the bills come due. Very few people actually watch those resources decreasing as they use them. It's impossible to watch fuel disappearing when it's burned in a power plant hundreds of miles away, and convenient to forget there's a connection. 用于制造这些物品的资源,仅仅是被当做一个价签来对待,在账单到期时供人们抱怨几句。极少有人在使用这些资源时真的看到它们在减少。当燃料是在几百英里以外的发电站里烧掉的时候,我们不可能看到它们消失;自然而然也就忘记这之间存在关联了。 When we use resources through technology that has to be tended, we're far more careful about how we use them. To use our antique space heater in the winter, I have to fill its reservoir with kerosene and keep its wick and flame spreader clean; when we want to use it, I have to open and light it. It's not a burdensome process, but it's certainly a more mindful one than flicking a switch. 当我们通过那些需要照看的技术来使用资源时,我们对于如何使用它们会更加仔细。冬天里,要用我们那件古董小暖炉的时候,我得往它的储液器里添煤油,保持灯芯和扩焰器干净;要用它时,我得打开它,然后点燃。这并非一件繁琐的事,但它确实比弹开一个开关要更费心思一些。 Not everyone necessarily wants to live the same lifestyle we have chosen, of course. But anyone can benefit from choices that increase their awareness of their surroundings and the way things they use every day affect them. 当然,未必所有人都想要过和我们选择的这般生活方式。但任何人都可以从这样一种选择中受益:这些选择将让他们更清晰的意识到周遭事物以及他们每日所用之物如何影响着他们。 Watching the level of kerosene diminish in the reservoir heightens our awareness of how much we're using, and makes us ask ourselves what we truly need. Learning to use all these technologies gives us confidence to exist in the world on our own terms. 看着储液器里煤油油位的下降,会提高我们对自己用了多少煤油的意识,促使我们追问自己,我们的真实需求是什么。学着使用所有这些技术,能让我们依照自己的方式充满自信地存在于这个世界。******

And that, really, is the resource we find ourselves more and more in need of. My husband and I have slowly, gradually worked to base our lives around historical artifacts and ideals because — quite frankly — we love living this way. 而这,我们发现,确实是我们日益需要的东西。我丈夫和我已经慢慢地、逐步地将我们的生活建基于历史物品和历史理念之上,因为——坦率地说——我们忠爱这种生活方式。 People assume the hard part of our lifestyle comes from the life itself, but using Victorian items every day brings us great joy and fulfillment. The truly hard part is dealing with other people's reactions. 人们以为我们生活方式的难处会在于这种生活本身,但是每天使用维多利亚时代的物品给我们带来的是极大的愉悦和满足。然而真正的困难却在于应付别人对此的反应。 We live in a world that can be terribly hostile to difference of any sort. Societies are rife with bullies who attack nonconformists of any stripe. 我们所生活的世界,对于任何差异都可能极为敌视。社会上充斥着欺凌,攻击任何形式的不循常规者。 Gabriel's workout clothes were copied from the racing outfit of a Victorian cyclist, and when he goes swimming, his hand-knit wool swim trunks raise more than a few eyebrows — but this is just the least of the abuse we've taken. Gabriel的运动服是某位维多利亚骑行者所用竞赛服的复制品,而当他去游泳时,他的手织羊毛制泳裤所得到的可不止是一点点异样眼光——这还只是我们所受伤害中最轻微的一类。 We have been called "freaks," "bizarre," and an endless slew of far worse insults. We've received hate mail telling us to get out of town and repeating the word "kill ... kill ... kill." Every time I leave home I have to constantly be on guard against people who try to paw at and grope me. 我们曾被称为“变态”、“怪异”,以及无穷尽的一堆更为不堪的辱骂。我们还收到过恐吓信,让我们离开镇子,并重复写有“杀……杀……杀”这个词。每次出门,我都得时刻保持警惕,防止人们抓我或者摸我。 Dealing with all these things and not being ground down by them, not letting other people's hostile ignorance rob us of the joy we find in this life — that is the hard part. By comparison, wearing a Victorian corset is the easiest thing in the world. 应付所有这类事情,不被它们打翻,不让其他人充满敌意的无知剥夺我们在这种生活中找到的快乐——这才是难点。与之相比,穿件维多利亚式的紧身胸衣就是世上最容易的事了。 This is why more people don't follow their dreams: They know the world is a cruel place for anyone who doesn't fit into the dominant culture. Most people fear the bullies so much that they knuckle under simply to be left alone. In the process, they crush their own dreams. 这就是为什么更多的人没有追随自己的梦想:他们知道,对于任何不一致遵从主导文化的人来说,世界是个残忍的地方。多数人如此恐惧欺凌,以至于轻言放弃,以便免受干扰。在此过程中,他们碾碎了自己的梦想。 (编辑:辉格@whigzhou) *注:本译文未经原作者授权,本站对原文不持有也不主张任何权利,如果你恰好对原文拥有权益并希望我们移除相关内容,请私信联系,我们会立即作出响应。——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

The Boston Tea Party Myth

波士顿倾茶事件的迷思

作者:The debunker @ 2013-1-18

译者:Yuncong Yang(@kingsmill)

校对: 小册子(@昵称被抢的小册子)

来源:UnpopularTruth.com,http://www.unpopulartruth.com/2009/04/boston-tea-party.html

The Boston Tea Party was not a protest against high taxes, but a protest of several things. Mostly it was an anti-monopoly protest. And it demonstrated colonial resistance to British interference in the American economy.

波士顿倾茶事件的目的并非抗议高额茶税,而是抗议其他一些东西,其中主要是反垄断。同时它也反映了当时美洲殖民地对英国插手殖民地经济的抵制。

A popular understanding of the Boston Tea Party is that the colonial Americans were protesting against high taxes on imported British tea. However, this is not the truth. This is a popular myth that this article clearly debunks. The truth is that the price of tea was actually lowered by the British. The lowering of the price was an attempt to give a monopoly to the East India Trading company. There were many reasons for the colonists to be angered by British manipulation and interference.

对波士顿倾茶事件的一种流行解读是:美洲殖民地的人民是要借倾茶抗议英国对进口的英国茶叶课以重税。然而这并非事实。本文就是要彻底打破这一广为流传的神话。实际上,英国人当时降低了茶叶价格,而压低茶叶价格是为了给予东印度公司垄断地位。英国的经济操纵与干涉之所以激怒了殖民者,是有多种原因的。

The Boston Tea Party, of course wasn’t an actual party, but was a famous incident in American history in which some American colonists in Boston disguised themselves as Indians and dumped chests of tea into Boston Harbor as a protest. This protest by American colonists arose from two issues confronting the British Empire in 1773: the financial problems of the British East India Company, and an ongoing dispute about the extent of Parliament’s sovereignty over the British American colonies.

“波士顿茶会”当然不是真正的茶会,它是美国历史上的一起重要事件。波士顿的一些美洲殖民者在事件中化装成印第安人登上了英国货船,把一箱箱的茶叶倒进波士顿港来表示抗议。美洲殖民者的反抗源于当时英帝国面临的两个问题:一是东印度公司的严重财政问题,二是有关议会对英属美洲殖民地管辖权限的争议。

******

(more...)******

American colonists resented this favored treatment of a major company, (East India Company) which employed lobbyists and wielded great influence in Parliament. At this stage in American history rebellion was brewing beneath the surface of society. Colonial protests resulted in both Philadelphia and New York, but it was those at the Boston Tea Party that made their mark on American history. 美洲殖民者反对英国当局给予一家大公司(东印度公司)特别优待,该公司雇佣了大量说客,在议会里影响很大。在美洲历史的这一时期,反抗的种子已经在土壤下悄悄萌芽了。在费城和纽约都出现了殖民者的抗议活动,但在美国历史上留下了印迹的,是波士顿的倾茶者们。 John Hancock organized a boycott of tea from China sold by the British East India Company, whose sales in the colonies then fell dramatically. By 1773, the company had large debts, huge stocks of tea in its warehouses and no prospect of selling it because smugglers, such as Hancock, were importing tea from Holland without paying import taxes. 约翰·汉考克组织了一场针对东印度公司销售的中国茶叶的抵制运动,结果东印度公司在殖民地的营业额一落千丈。到1773年,东印度公司已是债台高筑,货仓里积压了大批卖不出去的茶叶——也没有卖掉的指望,因为汉考克等走私贩子正在从荷兰走私大量茶叶到殖民地,这些茶叶是不用交关税的。 The British government passed the Tea Act, which allowed the East India Company to sell tea to the colonies directly and without "payment of any customs or duties whatsoever" in Britain, instead paying the much lower American duty. This tax break allowed the East India Company to sell tea for half the old price and cheaper than the price of tea in England, enabling them to undercut the prices offered by the colonial merchants and smugglers. 英国政府为此通过了《茶叶法案》,允许东印度公司直接向殖民地销售茶叶,不需要在英国国内“缴纳任何关税或其他税收”,而只需缴纳低得多的殖民地赋税。这一税收优惠使得东印度公司可以把它的茶叶价格削减一半,甚至比它在英国卖得还要便宜。现在东印度公司能以低于殖民地商人和走私贩的价格销售茶叶了。 Bostonians suspected the removal of the Tea Tax was simply another attempt by the British parliament to squash American freedom. Samuel Adams, wealthy smugglers, and others who had profited from the smuggled tea called for agents and consignees of the East India Company tea to abandon their positions; consignees who hesitated were terrorized through attacks on their warehouses and even their homes. 波士顿人怀疑,取消东印度公司的茶税,纯粹是英国议会压制美洲殖民地自由的又一次努力。塞缪尔·亚当斯,富有的走私贩子和其他从走私茶叶中获利的人们呼吁东印度公司在殖民地的代理商和经销商不要再和东印度公司合作。那些犹豫不决的经销商受到了恐吓,他们的货仓,有时甚至是住宅,都遭到攻击。 The Truth Behind the Boston Tea Party: The Tea Act Actually Lowered Taxes 倾茶事件背后的真相是:《茶叶法案》实际上降低了茶叶的税负。 Many people today think the Tea Act—which led to the Boston Tea Party—was simply an increase in the taxes on tea paid by American colonists. Instead, the purpose of the Tea Act was to give the East India Company full and unlimited access to the American tea trade, and exempt the company from having to pay taxes to Britain on tea exported to the American colonies. It even gave the company a tax refund on millions of pounds of tea they were unable to sell and holding in inventory. 如今很多人认为最终导致波士顿倾茶事件的《茶叶法案》提高了美洲殖民地人民负担的茶叶税额。但事实正相反。茶叶法案的目的是要让东印度公司能够完全不受限制的参与美洲茶叶贸易,并免除东印度公司向美洲出口茶叶时应在英国支付的税收。法案甚至为东印度公司卖不出去而积压在手里的数百万磅茶叶提供了退税。 One purpose of the Tea Act was to increase the profitability of the East India Company to its stockholders (which included the King), and to help the company drive its colonial small business competitors out of business. Because the company no longer had to pay high taxes to England and held a monopoly on the tea it sold in the American colonies, it was able to lower its tea prices to undercut the prices of the local importers and the mom-and-pop tea merchants and tea houses, not only in Boston, but in every town in America. 《茶叶法案》的目的之一是提高东印度公司的股东回报率(英王本人也是股东之一),并帮助东印度公司把在殖民地与它竞争的小公司赶出市场。因为东印度公司不必再付高昂的英国关税,并在殖民地市场出售茶叶方面享有专营权,所以它就可以通过价格竞争打败本地的进口商以及那些家庭式的茶商茶店。不仅在波士顿是如此,在每一个美洲城镇都是如此。 This meddling infuriated the independence-minded colonists, who were, by and large, unappreciative of their colonies being used as a profit center for the multinational East India Company corporation. One historical interpretation is that the truth of the Boston Tea Party is that it was a protest against this meddling. The American colonists resented their small businesses still having to pay the higher, pre-Tea Act taxes without having any say or vote in the matter. (Thus, the cry of "no taxation without representation!") 英国议会对茶叶市场的干涉激怒了当时已经有意独立的殖民者。总体来说,他们对英国议会拿他们的殖民地来为东印度公司这家跨国企业创造利润非常不满。对波士顿倾茶事件的历史解读之一是,倾茶事件表达了殖民者对这种干涉的抗议。美洲殖民者愤恨于他们的小茶行依然要支付《茶叶法案》出台之前的高税率,而且在这件事上他们一点发言权都没有(因此才有“无代表,不纳税!”的口号)。 Even in the official British version of the history, the 1773 Tea Act was a "legislative maneuver by the British ministry of Lord North to make English tea marketable in America," with a goal of helping the East India Company quickly "sell 17 million pounds of tea stored in England ..." 即使在英国官方版本的历史里,1773年《茶叶法案》也被描述为“诺思勋爵内阁为使英国茶叶在美国打开销路而采取的立法计谋”,其目的是帮助东印度公司迅速“卖掉积压在英国国内的一千七百万磅茶叶……” "Taxation Without Representation" had a Populist Context which plays a large role in the Boston Tea Party “无代表,强征税” 这一抗议有着民粹主义背景,这种背景在波士顿倾茶事件中影响很大。 "Taxation without representation" also meant hitting the average person and small business with taxes while letting the richest and most powerful corporation in the world off the hook for its taxes. It was government sponsorship of one corporation over all competitors. “无代表,强征税”这句话的另一层意思是,政府以税收打击普通百姓和小企业,却让世界上最大最富有的公司免于税收之累。实质上,这就是政府扶持一家公司而打击所有竞争对手。 The Boston Tea Party Was Similar to Modern Day Anti-globalization Protests 波士顿倾茶事件很像今天的反全球化示威 The Boston Tea Party resembled in many ways the growing modern-day protests against transnational corporations and small-town efforts to protect themselves from chain-store retailers or agricultural corporations. With few exceptions, the Tea Party's participants thought of themselves as protesters against the actions of the multinational East India Company and the government that "unfairly" represented, supported, and served the company while not representing or serving the residents. 波士顿倾茶事件和今天的反跨国公司示威,以及小城镇为免受连锁零售商或农业大公司侵蚀而做出的自我保护,在许多方面都颇为相似。绝大多数倾茶事件的参与者认为他们的抗议对象是跨国运营的东印度公司及政府,英国政府“不公平的”代表着东印度公司的利益,它支持并服务于东印度公司,而非殖民地的居民们。******

In England, Parliament gave the East India Company what amounted to a monopoly on the importation of tea in 1698. When tea became popular in the British colonies, Parliament sought to eliminate foreign competition by passing an act in 1721 that required colonists to import their tea only from Great Britain. But many Americans purchased the less expensive, smuggled Dutch tea. 在英国,议会在1698年给了东印度公司实质上的茶叶进口专营权。当茶叶在海外的英国殖民地也开始变得抢手时,议会为消除来自海外的竞争于1721年通过了法案,要求各殖民地只能从英国进口茶叶。但许多美洲殖民者选择购买较廉价的荷兰走私茶。 The East India Company did not export tea to the colonies; by law, the company was required to sell its tea wholesale at auctions in England. British firms bought this tea and exported it to the colonies, where they resold it to merchants in Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston. 东印度公司当时并不直接向各殖民地出口茶叶。按照法律,东印度公司须将其茶叶在英国通过拍卖批发出去。英国企业将买到的这些茶叶出口到殖民地,然后再转卖给波士顿,纽约,费城和查尔斯顿的商人们。 In order to help the East India Company compete with smuggled Dutch tea, in 1767 Parliament passed the Indemnity Act, which lowered the tax on tea consumed in Great Britain, and gave the East India Company a partial refund of the duty on tea that was re-exported to the colonies. To help offset this loss of government revenue, Parliament also passed the Townshend Revenue Act of 1767, which levied new taxes, including one on tea, in the colonies. Instead of solving the smuggling problem, however, the Townshend duties renewed a controversy about Parliament's right to tax the colonies. 为了帮助东印度公司与荷兰走私茶竞争,1767年议会通过了《免责法案》,该法案降低了英国国内消费茶叶的税率,并对经中间商再出口到殖民地的那部分茶叶退还部分关税给东印度公司。为弥补因此造成的政府收入减少,议会又通过了1767年的《汤森德税收法案》。该法案对殖民地开征了一些新税种,其中之一就是针对茶叶。然而新法案并没有解决茶叶走私问题,其规定的新税种却再度引发了有关议会对殖民地征税权的争议。 To fully understand the resentment of the colonies to Great Britain and King George III, one must understand that there were a series of events in which the colonists were treated unfairly. In previous years, the 13 colonies saw a number of commercial tariffs including the Sugar Act of 1764, which taxed sugar, coffee, and wine, the Stamp Act of 1765, which put a tax on all printed matter, such as newspapers and playing cards, and the Townshend Acts of 1767 which placed taxes on items like glass, paints, paper, and tea. The Tea Act of 1773 was the last straw. 要全面理解殖民地对英国及英王乔治三世的反感,就必须要意识到当时在一系列的事件中,殖民者都已经受到了不公平的待遇。在此前十多年中,十三个殖民地被加征了一系列的新税:1764年的《糖业法案》对糖,咖啡和葡萄酒征税;1765年的《印花税法》对上至报纸下至扑克牌的所有印刷品征税;1767年的《汤森德法案》则对诸如玻璃,油漆,纸和茶叶等货品征税。1773年的《茶叶法案》不过是最后一根稻草罢了。 "If our trade be taxed, why not our lands, in short, everything we posses? They tax us without having legal representation." —Samuel Adams “如果他们能对我们的贸易征税,那为什么就不能对我们的土地,或者我们所有的一切征税?他们向我们征税,却不给我们法定代表权。”——塞缪尔·亚当斯 In an attempt to transfer part of the cost of colonial administration to the American colonies, the British Parliament had enacted the Stamp Act in 1765 and the Townshend Acts in 1767. Colonial political opposition and economic boycotts eventually forced repeal of these acts, but Parliament left the import duty on tea as a symbol of its authority. Under the Townshend Act, many goods brought into the colonies were heavily taxed by the British. To attempt to appease the disgruntled Americans, these tariffs were repealed, except for tea, and they remained upset since the tax on tea remained in effect. 为了把管理殖民地的成本部分转嫁给美洲殖民地,英国议会于1765年通过了《印花税法》,于1767年通过了《汤森德法案》。殖民地的政治反抗和经济杯葛最终迫使议会废除了这些法律,但议会保留了茶叶进口的关税,作为其对殖民地握有管辖权的标志。按照汤森德法案,英国人对殖民地进口的许多商品都征收了重税。然后,为了安抚愤怒的殖民地人,除茶税外,所有这些关税都被废除了。但是殖民者依然不满,因为英国还在征收着茶税。 In an atmosphere of continuing suspicion and distrust, the British and Americans each looked for the worst from the other. In 1772 the crown, having earlier declared its right to dismiss colonial judges at its pleasure, stated its intention to pay directly the salaries of governors and judges in Massachusetts. 在长期持续的猜疑与不信任的气氛下,英国人和殖民者都在以最大的恶意揣测着对方。在1772年,王国政府宣布它有意直接向马萨诸塞的行政长官及法官们发放薪金。而在此前不久,它已宣称有权随意罢免殖民地的法官。 The situation remained comparatively quiet until May 1773, when the faltering East India Company persuaded Parliament that the company's future and the empire's prosperity depended on the disposal of its tea surplus. At this point, the East India Company was facing bankruptcy due to corruption, mismanagement, and competition. 直到1773年5月,形势还是相对平静的。就在5月,摇摇欲坠的东印度公司终于说服议会,东印度公司的未来及帝国的福祉都取决于手中积压的茶叶能否得到处理。此时,东印度公司已经因腐败,管理不善和市场竞争而濒临破产了。 The plan was to export a half a million pounds of tea to the American colonies for the purpose of selling it without imposing upon the company the usual duties and tariffs. With these privileges, the company could undersell American merchants and monopolize the colonial tea trade. Not only did this action create unfair commerce for the merchants of the colonies but it also proved to be the spark that revived American passions about the issue of taxation without representation. 东印度公司的计划是:将五十万磅茶叶卖到美洲殖民地去,政府将不对这些茶叶征收关税和其他赋税。有了这样的优惠条件,东印度公司就可以通过价格竞争挤掉美国茶商,进而垄断殖民地的茶叶市场。这一行动不仅仅对殖民地商人不公,事实证明,它还是一根导火索,重新点燃了殖民者对“无代表,强征税”的怒火。 Because the American tea market had nearly been captured by tea smuggled from Holland, Parliament gave the company a drawback (refund) of the entire shilling-per-pound duty, enabling the company to undersell the smugglers. It was expected that the American colonists, faced with a choice between the cheaper company tea and the higher-priced smuggled tea, would buy the cheaper tea, despite the tax. The company would then be saved from bankruptcy, the smugglers would be ruined, and the principle of parliamentary taxation would be upheld. 因为当时美洲茶叶市场已经基本被荷兰走私茶占领,议会决定将每磅一先令的茶叶关税全额退还给东印度公司,使之能借价格优势击败走私商人。议会认为,尽管有茶税,殖民者在便宜的东印度公司茶和较贵的走私茶中,应该还是会选择便宜茶的。这样既可以挽救东印度公司,使之免于破产,又可以将走私商人赶入绝境,还可以继续维持议会在殖民地征税的权威。 Resisting the Tea Act 反抗茶叶法案 Due to the popularity of inexpensive tea smuggled from Holland, British tea manufacturers were accumulating a large surplus of unsold tea, about 17 million pounds. 因为较为便宜的荷兰走私茶在市场上大为走红,英国茶厂积压了大量的滞销茶叶,累计达一千七百万磅之多。 Instead of rescinding the remaining Townshend tax and exploring inoffensive methods of aiding the financially troubled British East India Company,Parliament enacted the Tea Act of 1773, designed to allow the company to bypass middlemen and sell directly to American retailers 面对这种情况,议会并没有选择废除残余的汤森德税,也没有试图寻求不损害别人的办法来拯救东印度公司。相反它颁布了1773年《茶叶法案》,允许东印度公司不经中间商直接向美洲零售商销售茶叶。 In September and October 1773, seven ships carrying East India Company tea were sent to the colonies: four were bound for Boston, and one each for New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston. Americans learned the details of the Tea Act while the ships were en route, and opposition began to mount. Whigs, sometimes calling themselves Sons of Liberty, began a campaign to raise awareness and to convince or compel the consignees to resign, in the same way that stamp distributors had been forced to resign in the 1765 Stamp Act crisis. 1773年九月和十月间,七艘满载东印度公司茶叶的货船驶向殖民地,四艘前往波士顿,剩下三艘分别前往纽约,费城和查尔斯顿。这些船还在路上时,美洲殖民者就已经得知《茶叶法案》的细节,反抗情绪在逐步酝酿。有时自称“自由之子”的北美辉格党人发起了一场旨在让公众了解《茶叶法案》并说服或迫使东印度公司的分销商们放弃分销权的运动。在1765年《印花税法案》风波里,他们正是以这种方式迫使印花税票分销商放弃销售权的。 The truth is that the protest movement that culminated with the Boston Tea Party was not a dispute about high taxes. The price of legally imported tea was actually reduced by the Tea Act of 1773. Protestors were instead concerned with a variety of other issues. 事实上,以波士顿倾茶事件为终结的抗议运动并不是针对高税率的。1773年的《茶叶法案》事实上降低了合法进口茶叶的价格。抗议者们关心的是其他一些问题。 Several myths are wrapped up in the story of the Boston Tea Party. The familiar "no taxation without representation" argument, along with the question of the extent of Parliament's authority in the colonies, remained prominent. 波士顿倾茶事件的叙述里包含了若干迷思。广为人知的“无代表不纳税”主张,和议会的殖民地管辖权范围问题,至今仍在叙事中居于突出地位。 Some regarded the purpose of the tax program—to make leading officials independent of colonial influence—as a dangerous infringement of colonial rights. This was especially true in Massachusetts, the only colony where the Townshend program had been fully implemented. 另一些人认为,英国的征税方案旨在令殖民地高级官员免受殖民地影响,这是对殖民地权利的严重侵犯。这一说法在马萨诸塞格外真确,因为马萨诸塞是唯一一个完全执行了汤森德增税计划的殖民地。 Colonial merchants, some of them smugglers, played a significant role in the protests. Because the Tea Act made legally imported tea cheaper, it threatened to put smugglers of Dutch tea out of business. Other, legal tea importers who had not been named as consignees by the East India Company were also threatened with financial ruin by the Tea Act. 殖民地商人们——其中一些是走私者——在抗议中扮演了重要角色。因为《茶叶法案》降低了合法进口茶叶的价格,走私荷兰茶的商人们可能会被挤出市场。此外,那些没有得到东印度公司授权经销资格的合法进口茶商们也面临灭顶之灾。 Another major concern for merchants was since the Tea Act gave the East India Company a monopoly on the tea trade, it was feared that this government-created monopoly might be extended in the future to include other goods. And this served to alarm the conservative colonial mercantile elements into uniting with the more radical patriots. 商人们担忧的另一重点是《茶叶法案》使东印度公司垄断了茶叶贸易市场,而未来这种政府支持的垄断行为也可能扩展到其他的商品交易上。这些威胁刺激了较为保守的殖民地商界势力,使之逐渐与更激进的反英志士群体联合起来。 South of Boston, protestors successfully compelled the tea consignees to resign. Merchants agreed not to sell the tea, and the designated tea agents in New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston canceled their orders or resigned their commissions. 在波士顿南部,抗议者们成功迫使东印度公司的授权分销商放弃了分销权。商人们同意抵制东印度公司的茶叶。在纽约,费城和查尔斯顿,取得茶叶分销权的代理商们或取消订单,或放弃分销权。 In Charleston, the consignees had been forced to resign, and the unclaimed tea was seized by customs officials. There were mass protest meetings in Philadelphia, and eventually the Philadelphia consignees had resigned and the tea ship returned to England with its cargo. The tea ship bound for New York City was delayed by bad weather; by the time it arrived, the consignees had resigned, and the ship returned to England with the tea. 在查尔斯顿,授权经销商们被迫放弃了经销权,无人售卖的茶叶最后被海关官员扣押了。费城爆发了大规模的抗议集会,最终费城的授权经销商们也退出了,运茶船带着茶叶打道回府。前往纽约的运茶船被海上的恶劣天气耽搁了,等到它到达纽约时,当地的经销商们已放弃了经销权,它只好又带着茶叶回了英国。 Revolutionary sentiment mounted . . . 革命情绪升温…… In Boston, however, the tea consignees were friends or relatives of Governor Hutchinson, who was determined to uphold the law. The opposition, led by Samuel and John Adams, Josiah Quincy, and John Hancock, was determined to resist Parliamentary supremacy over colonial legislatures. 然而在波士顿,茶叶授权经销商们都是总督哈钦森的亲友,而哈钦森决意要实施《茶叶法案》。由塞缪尔和约翰·亚当斯两兄弟,约书亚·昆西和约翰·汉考克领导的反对派则决心抵抗议会凌驾于殖民地立法机构之上的威权。 Three ships from London, the Dartmouth, the Eleanor and the Beaver, sailed into Boston Harbor from November 28th to December 8, 1773. Loaded with tea from the East India Company, they were all anchored at Griffin’s Wharf but were prevented from unloading their cargo. 从伦敦来的三艘货船——达特茅斯号,艾莉诺号和河狸号——于1773年11月28日到12月8日间驶入波士顿港。三艘船满载东印度公司的茶叶,停泊在格里芬码头,但它们无法卸货。 When the first ship, the Dartmouth, reached Boston with the cargo of tea, the Sons of Liberty prevented owner Francis Rotch from unloading the tea, but they could not force the consignees to reject it. Rotch and the captains of two newly arrived ships, the Eleanor and the Beaver, agreed to leave without unloading the tea, but they were denied clearance by Governor Hutchinson. 当达特茅斯号运载茶叶首先到达波士顿时,“自由之子”成功阻止了船主弗朗西斯·罗奇卸货,但他们无法迫使授权经销商们拒绝接受这些茶叶。罗奇和另两艘刚到达的船——艾莉诺号和河狸号——的船长们同意不卸货就离开波士顿,但总督哈钦森拒绝放行。 According to the law, if the tea was not unloaded within 20 days (by December 17), it was to be seized and sold to pay custom duties. Convinced that this procedure would still be payment of unconstitutional taxes, the radical patriots resolved to break the deadlock. On December 14, Rotch was called before a mass meeting and ordered to seek clearance again to sail from Boston. But neither the customs collector nor the governor would grant it. 按照法律,如果这些茶叶不能在20天内(也就是到12月17日)卸下船,它们将会被海关没收拍卖来偿付关税。激进的反英志士们认为这样处理茶叶无异于缴纳违宪征收的茶税,于是他们决定要打破眼前的僵局。12月14日,志士们将罗奇船长召至一次大型集会上,并命令他再次申请驶离波士顿港,但无论是海关还是总督都拒绝放行。 Fearing that the tea would be seized for failure to pay customs duties, and eventually become available for sale, something had to be done. Demanding that the tea be returned to where it came from or face retribution, the Sons of Liberty, led by Samuel Adams began to meet to determine the fate of the three cargo ships in the Boston harbor. 如果不想让茶叶因滞纳关税被扣押拍卖而最终流入市场,就必须要采取行动了。塞缪尔·亚当斯领导的“自由之子”一方面声称如果这些茶叶不运回英国,他们就将采取报复行动,另一方面开始组织会议,讨论应该如何处理波士顿港内的这三艘货船。 On the cold evening of December 16, 1773, a crowd of several thousand spectators gathered and shouted encouragement to about 60 men disguised as Mohawk Indians. The band of patriots in Boston burst from the South Meeting House with the spirit of freedom burning in their eyes. The patriots headed towards Griffin's Wharf and the three ships. Quickly, quietly, and in an orderly manner, they boarded each of the tea ships. Once on board, the patriots went to work striking the chests with axes and hatchets. 1773年12月16日,一个寒冷的夜晚,波士顿街头聚集了几千名看热闹的群众,他们高声呐喊,为约六十名乔装成印第安莫霍克族的志士助威。这一伙波士顿反英志士从南方教堂议事厅冲了出来,他们个个眼中都燃烧着自由的火焰,冲向格里芬码头的三艘货船。志士们飞速而有序的分别登上了三艘货船,没有发出一点声音。一上船,他们就开始用斧头劈砍茶叶箱子。 Only the sounds of axe blades splitting wood rang out from Boston Harbor. Once the crates were open, the patriots dumped the tea into the sea. By nine o'clock p.m., the Sons of Liberty, with the aid of the ships' crew, had emptied a total of 342 crates of tea into Boston Harbor. Fearing any connection to their treasonous deed, the patriots took off their shoes and they swept the ships' decks, and made each ship's first mate attest that only the tea was damaged. 静悄悄的波士顿港里,只听到斧刃劈开木箱的声音。劈开箱子之后,志士们就把茶叶倒入海里。到晚上九点,“自由之子”们在船员的帮助下已经把三百四十二箱茶叶倒进了波士顿港。为免事后被发现他们与这一叛逆行径有何干系,志士们脱掉鞋子,擦干净了货船的甲板,并让各船大副宣誓作证:船上受损的只有茶叶,并无他物。 The furious royal government responded to this "Boston Tea Party" by the so-called Intolerable Acts of 1774, practically eliminating self-government in Massachusetts and closing Boston's port. 愤怒的英国政府对“波士顿倾茶事件”做出了反应,它颁布了被后世称为“1774年不可容忍法案”的一系列法律。通过这些法律,英国政府实质上取消了马萨诸塞的自治,并关闭了波士顿港。 The news of the destruction of the tea raised the spirit of resistance in the colonies. On April 22, 1774, the London attempted to land tea at New York. It was boarded by a mob, and the tea was destroyed. Similar incidents occurred at Annapolis, Md., on October 19 and at Greenwich, N.J., on December 22, and the tea was boycotted throughout the colonies. 倾茶事件的消息传遍了美洲殖民地,鼓舞着殖民地人民的反抗斗志。在1774年4月22日,伦敦号货船试图在纽约卸茶,结果一伙暴民登船毁掉了所有的茶叶。同年10月19日,马里兰州安纳波利斯也发生了同样的事件。12月22日,毁茶事件在新泽西州格林威治再度发生。所有殖民地都在杯葛英国茶叶了。 (编辑:辉格@whigzhou) *注:本译文未经原作者授权,本站对原文不持有也不主张任何权利,如果你恰好对原文拥有权益并希望我们移除相关内容,请私信联系,我们会立即作出响应。——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

【2016-01-19】

@大象公会 【为什么南方多江,北方多河?】为什么中国河流南方多称为“江”,北方多称为“河”?“江”、“河”又如何从长江黄河的专称泛化为一般河流通名?移民又是如何改变“江”、“河”的分布的?作者:@Serpens 、@qqflyaway_PKU

@whigzhou: 好文,不过,“上古时期,黄河中上游植被条件尚好,泥沙含量较少,下游地区尚能保持比较稳定的河道。……黄河有文字记载的第一次大决口在周定王五年(公元前 602 年),此前黄河自(more...)

权力积木#2:信息与控制

辉格

2015年12月3日

一个广域国家的统治者面临各种技术难题,比如在前文已讨论过的领地安全问题中,为了对入侵和叛乱做出及时反应,他不仅需要机动优势,还需要以5-10倍于行军的速度传送情报,而即便如此,当疆域非常广阔时,也必须在多个据点驻扎军队,而不能集中于一点;行政系统也是如此,为实现有效治理,广袤领地须划分成若干单元,分别派驻官吏。

更一般而言,当统治团队膨胀到一定程度时,由于它本身也受制于邓巴局限,因而只能建立层级组织,假设按每个上级单元控制20个下级单元(1:20已经是非常扁平的结构,只能实现较弱的控制,有关这一点我以后会展开讨论),那么,从一两百人的熟人小社会到数千万人的帝国,就至少需要四个层级。

然而,一旦建立层级组织,就会面临所有委托-代理关系中都存在的激励和控制难题,瞒上欺下,职权滥用,目标偏离,推诿责任,沟通不畅,协调失灵,以及最危险的背叛和分离;最高权力者总会想出各种办法来克服这些障碍,那些或多或少管用的办法就被延用下来,构成了我们在历史中所见到的种种政体结构、制度安排和组织工具。

防止叛乱的一种方法是多线控制,将维持下级单元运行所需职能加以分割,交给不同人掌管,并通过不同的层级系统加以控制,使得其中每个都无法单独行动,从而剥夺下级单元的独立性;例如,由将领掌握军队指挥权,由行政系统负责粮草供给,这样,叛军很快会因失去粮草而陷入瘫痪。

另一种方法是阻止上下级官员之间发展私人效忠关系,缩短任期、频繁调动、任职回避、把奖励和提拔权限保留在高层,都是出于这一目的;另外,在重臣身边安插耳目,派出巡回监察官,维持多个独立情报来源,要求同级官员分头汇报情况以便核查真伪虚实,都是常见的做法。

强化控制的终极手段,是直接发号施令,让官员忙于执行频繁下达的任务而无暇追求自己的目标,甚至让他们看不清系统的整体运营机制因而无法打自己的小算盘;爱德华·科克(Edward Coke)有句名言:(大意)“每天起床都要等着别人告诉他今天要做什么的人,肯定是农奴。”当控制强化到极致时,臣僚便成了君主的奴仆。

当然,这些做法都是有代价的,多线控制削弱了下级单元的独立应变能力,面对突发危机时,协调障碍可能是致命的;在古代的组织条件下,消除个人效忠也会削弱军队的战斗力,这一点在历史上已屡屡得到证明,较近的例子是,湘军的战斗力很大程度上依靠曾国藩等人所建立的个人效忠网络,北洋新军相对于绿营清军的一大优势也是个人效忠。

然而,更重要的是,所有这些方法都有一个共同前提:高速通信;多线控制下,军队和粮草都可囤在前线基地,但指令必须由上层发出,平时被刻意隔离的几套体系,离开中央指挥就难以协调行动;同样,有效的监视、巡察、考核、奖惩,也都依赖于快速高效的情报传递,直接遥控指挥更需要近乎于实时的通信能力;正因此,所有帝国都建立了效率远远超出同时代民用水平的通信系统。

自从定居之后,便有了入侵警报机制,发现盗贼时,人们以鸣锣呼喊等方式通知邻居,循声追捕(hue and cry)是中世纪英格兰社区对付盗贼的惯常方法,只要盗贼还没离开视线,所有目击者都有义务追呼,hue的拉丁词源可能是hutesium(号角),和铜锣一样,号角也是用于警报的通信工具。

当部落扩大到多个村寨时,功率更大的鼓就被用于远程警报,流行于百越民族的铜鼓,可将信号传出几公里乃至十几公里,经接力传递更可达上百公里,由于铜鼓的覆盖范围大,也被长老和酋长们用于召集民众,因而成为权威和共同体凝聚力的象征,类似于欧洲市镇的钟楼;钟鼓楼也是古代中国行政城市的标准配置,其象征意义毋庸置疑。

非洲人将鼓的通信功能发挥到了极致,通常,鼓只能通过节奏变化编码少量信息,带宽十分有限,但西非人凭借可调音高的沙漏状皮带鼓创造了一种能够传递丰富信息的鼓语(talking drum),用音调变化模拟语音流,效果类似于闭着嘴用鼻音说汉语。

因为班图语和汉语一样也是声调语言(tonal language),这样的模拟确实可行,当然,去掉元辅音丢失了大量信息,听者很难猜到在说什么,特别是失去当面对话中的手势体态环境等辅助信息之后,为此,鼓语者会附加大量冗余来帮助听者还原:重复、排比、修饰,把单词拉长成句子,插入固定形式的惯用短语来提示上下文,等等,长度加长到所模拟语音的五六倍。

鼓语不仅被用于在村庄之间传讯,也被大量用于私人生活,召唤家人回家,通知有客来访,谈情说爱,或只是闲聊,在20世纪上半叶鼓语还盛行时,人人都有一个鼓语名;不过,自发形成的鼓语毕竟不够精确,难以满足军事和行政需要,阿散蒂(Ashanti)和约鲁巴( 标签:

权力积木#1:距离与速度

辉格

2015年11月21日

国家最初源自若干相邻酋邦中的最强者所建立的霸权,而这些酋邦则由专业武装组织发展而来;霸权当然首先来自压倒性的武力优势:霸主能够轻易击败势力范围内的任何对手,并且所有各方都十分确信这一点,因而甘愿向它纳贡称臣,也愿意在自身遭受威胁时向它求助,卷入纠纷时接受其仲裁,发生争霸挑战时站在它那一边。

然而,武力是起落消长多变的,仅凭一时之战斗力而维持的霸权难以长久,要将围绕霸权所建立的多边关系常规化和制度化,需要更多权力要素;要理解这些要素如何起源,以及它们在支撑国家权力中所履行的基础性功能,我们最好从多方博弈的角度出发,考虑其中的利害权衡。

通常,霸主最需要担心的是这样几种情况:1)在属邦遭受攻击时不能及时提供援助,丧失安全感的属邦可能转而投靠其他霸主,2)当一个属邦反叛并攻击其他属邦时,若不能及时加以制止,便可能引发连锁反应,3)当足够多属邦联合协调行动发动叛乱时,霸主的武力优势被联合力量所压过。

无论何种情况,当事方对霸主行动速度的预期都是关键所在,若遭受攻击的弱小属邦预期得不到及时救援,便可能放弃抵抗而选择投降,若邻近敌邦预期能在援兵到达之前得手并及时撤离,便更可能发动攻击,若潜在叛乱者预期自己有能力在霸主赶来镇压之前连克多个属邦并吸引到足够多追随者,便更可能发动叛乱,而当叛乱实际发生时,那些骑墙观望的属邦,若预期霸主无力及时平定叛乱,便更可能加入叛军行列,特别是当他们原本就心怀不满,或与反叛者关系亲密,或早有争霸野心时。

所以,对于维持霸权,仅有强大战斗力是不够的,还要有机动性,能够将兵力及时投送到需要的地方,速度要比对手快;设想这样一种简化的情形:霸主甲位于属邦乙的南方60英里,敌邦丙由北向南进攻乙,位于乙之北60英里的边境哨所得到敌情后向甲和乙汇报,假如所有人的行动速度都是每天10英里,那么丙就会早于甲的援军至少6天到达乙地,假如乙预期撑不过6天,就可能早早选择投降。

但是,假如报信者每天能跑60英里,而甲的行军速度是2倍于敌军的每天20英里,加上一天的集结时间,援军仍可与敌军同时到达,换句话说,上述情境中,只要通信速度6倍于敌军行军速度,己方行军速度2倍于敌方,霸主便能有效保护属邦,若机动优势降至1.5倍,也只需要属邦能抵抗一天,或者,即便机动优势只有1.2倍,霸主也完全来得及在敌军得手撤离之前追上它并实施报复,而及时报复能力是对潜在侵犯者的有力威慑。

这虽然是简化虚构,但离现实并不太远,古代军队的行军速度很慢,晴天陆地行军速度一般不超过每天10英里,雨天则几乎走不动,而无论是青铜时代的城邦霸主,还是铁器时代的大型帝国,机动优势都构成了其霸权的核心要素。

公元前15世纪的埃及战神图特摩斯三世(Thutmose III)在其成名之战米吉多战役(Battle of Megiddo)中,在9天内将2万大军投送到250英里之外的加沙,将近3倍于常规速度;从波斯、马其顿到罗马,这些辉煌帝国的一大共同点是:都有能力以2到3倍于对手的速度大规模投送兵力,同时以5至10倍于常规行军的速度传递消息。

古代行军速度慢,不是因为人跑的慢,相反,人类特别擅长超长距离奔跑,大概只有袋鼠、鸵鸟和羚羊等少数动物能与人媲美,长跑也是早期人类狩猎技能的关键,我们的脊柱、骨盆、腿骨、颈部肌肉、脚趾、足弓和汗腺,都已为适应长跑而大幅改造,运动生理学家发现,对于长距离奔跑,两足方式比四足方式更加高效节能,尽管后者能达到更高的瞬间速度。

卡拉哈里的桑族猎人经常在40度高温下连续三四小时奔跑三四十公里直至将猎物累垮,美国西南部的派尤特(Paiute)印第安人逐猎叉角羚时,澳洲土著追逐大袋鼠时,也采用类似方法;当距离超出100公里时,人的速度便可超过马;居住在墨西哥高原奇瓦瓦州的美洲土著塔拉乌马拉人(Tarahumara)很好的展示了人类的超长跑能力,在他们的一项传统赛跑活动中,参赛者可以在崎岖山路上两天内奔跑300多公里。

拖慢行军速度的,是后勤补给负担,这一负担因国家起源过程中战争形态的改变而大幅加重,原因有三个:首先,大型政治实体的出现成倍拉大了作战距离,在前国家的群体间战争中,作战者通常可以当天往返,无须携带补给品,在酋邦时代,相邻酋邦之间相距几十公里,军队也最多离家一两天,但广域国家的军队常常需要到数百上千公里外作战,短则几(more...)

【2015-12-10】

@baidu冷兵器吧 依靠以自豪感为目的的历史教育和许多义和团知识分子们,总是强调老欧洲粪便垃圾满地污水横流,街道如何狭窄等等,以此制造一种印象——虽然近现代我们是不行了,可是我们祖宗可比西方祖宗阔的多啦,不用去学什么鸟西方!但,中国真能嘲笑古代欧洲脏乱差吗? http://t.cn/RUsEyYH 中国能嘲笑古代欧洲脏乱差吗?

@战争史研究WHS:汉长安城至北周时“水皆咸卤,不甚宜人”,这个水指的是地下水。八百年间城市粪尿渗入地表,(more...)

过感恩节,“白人屠杀印第安人”的话题又冒了出来,大伯我也说两句。

1)所谓种族灭绝当然是胡扯,极左分子新近编造的“人民历史”,不值一驳;

2)殖民者与土著确实有不少冲突,其中一个重要原因是定居者与非定居者对土地权利有着截然不同的观念;

3)殖民早期这个问题并不太严重,因为相对于北美的广阔地域,殖民者人数极少,他们与土著所偏爱的生态位也十分不同;

4)殖民者与印第安人的关系因美国独立而大幅恶化,后来的西进运动(特别是铁路开始向西延伸后)更加剧了冲突,时而发展成战争;

5)这一(more...)