The Most Misunderstood Libertarian

最为人所误解的自由意志主义者

作者:

Alberto Mingardi @ 2015-9-28

译者:沈沉(@你在何地-sxy)

校对:混乱阈值(@混乱阈值)

来源:Library of Law & Liberty,

http://www.libertylawsite.org/book-review/the-most-misunderstood-libertarian/

To the surprise of many, scholarship on Herbert Spencer (1820-1903) has flourished in the last few years. A towering figure in Victorian Britain, Spencer was all but forgotten after his death. His works, which taken together form a “Synthetic Philosophy,” seemed alien to 20th century academics in an age of meticulous specialization. Also his commitment to individual liberty and (seriously) limited government has not been too common in the discipline that he helped establish, sociology. Talcott Parsons famously called him a victim of the very God he adored: evolution.

关于赫伯特·斯宾塞(1820-1903)的学术研究过去几年活跃了起来,这让许多人感到惊讶。斯宾塞是英国维多利亚时代的一位杰出人物,死后却几乎被人遗忘。他的各种著作构成一个“综合哲学”整体,与20世纪专业细分的学术界格格不入。并且,他对个体自由和(极度的)有限政府的信奉,在他所帮助建立的社会学学科中历来并不十分流行。塔儿科特·帕森斯曾出了名地把他称为他所推崇的那个上帝——进化——的牺牲品。

Toward the end of the 20th century, however, interest in Spencer began to revive. In 1974, J.D.Y. Peel published

Herbert Spencer: The Evolution of a Sociologist and Robert Nisbet dealt at length with Spencer in his 1980

History of the Idea of Progress. In

Anarchy, State and Utopia (1974), Robert Nozick adapted his “tale of the slave” on taxation and democracy from Spencer’s 1884

The Man versus the State. In 1982, the journal

History of Political Thought published contributions on Spencer from John Gray, William Miller, Jeffrey Paul, and Hillel Steiner that remain a landmark.

不过,到20世纪快要结束时,人们又重新燃起对斯宾塞的兴趣。1974年,J. D. Y. Peel出版了《赫伯特·斯宾塞:一位社会学家的进化》;1980年,Robert Nisbet在其《进步观念史》中对斯宾塞进行了长篇讨论。在《无政府、国家与乌托邦》(1974)中,罗伯特·诺齐克讨论税收和民主问题时所用的“奴隶的故事”源自于斯宾塞1884年的著作《人与国家》。1982年,《政治思想史》杂志刊登了John Gray、William Miller、Jeffrey Paul和Hillel Steiner等人论斯宾塞的多篇文章,至今仍有里程碑意义。

New monographs and studies were later published, and today a number of scholars in different disciplines (history of political thought, sociology, anthropology) can be counted among the Spencer connoisseurs. But few of them have come from the classical liberal camp. (The most notable exception is George H. Smith.)

其后关于斯宾塞的新专著和新研究时有出现。时至今日,分处不同领域(政治思想史、社会学、人类学)的许多学者可以被视为斯宾塞行家。但其中几乎无人来自古典自由主义阵营。(George H. Smith是最著名的例外。)

Spencer may be routinely included among the forerunners of modern libertarianism but it is rather uncommon to find a contemporary individualist thinker deliberately appealing to his insights. Take F.A. Hayek: Long ago, John Gray pointed out that Hayek and Spencer share the “same aspiration of embedding the defense of liberty in a broad evolutionary framework,” but Hayek himself appeared to have been largely unaware of this affinity. More recently,

Gray wrote that Hayek told him he never read Spencer.

斯宾塞或许会被习惯性地列为现代自由意志主义的先驱之一,但要在当代个人主义思想家中找到一个刻意诉诸斯宾塞见解的人,这可并非易事。以F. A. 哈耶克为例:John Gray早已指出哈耶克和斯宾塞都具有“同一种抱负,那就是把对自由的辩护牢固树立于一种广义的进化论框架中”,但哈耶克本人似乎基本上没有意识到这种共鸣。最近,Gray写道,哈耶克曾告诉他说自己从没读过斯宾塞。

The paradox of one of the fiercest libertarians ever to be ignored by libertarians emerges vividly from

Herbert Spencer: Legacies, edited by Mark Francis and Michael Taylor. Interestingly, the two editors have published extensively on Spencer in the past, but their interpretations of him do not overlap.

史上最为狂热的自由意志主义者之一却被自由意志主义者们所忽略,这一乖谬在由Mark Francis和Michael Taylor主编的《赫伯特·斯宾塞:遗产》一书中表现得极为生动。有趣的是,两位主编过去都已就斯宾塞发表过大量文章,不过他们各自对斯宾塞的解读并不相同。

Francis, as he attempts to rescue Spencer’s philosophy from oblivion, in his Introduction calls

The Man Versus the State and also

Social Statics (1851) “popular works” that, “while they were liberal and progressive, . . . were not scientific or philosophical.” Taylor, in contrast, deals at length with

Social Statics—as Stephen Tomlinson does in his chapter in this volume.

Francis尝试将斯宾塞的哲学从被人遗忘的状态中拯救出来,并在他为该书所写的“导论”中将《人与国家》和《社会静力学》(1851)称为“流行作品”,“尽管是自由主义、进步主义的……并不具备科学性或哲学性”。与之相反,Taylor则对《社会静力学》进行了长篇讨论——同书中由Stephen Tomlinson所写的一个章节也是如此。

Spencer’s legacy is plural, as the title of this collection suggests, and may have come to us mediated by subsequent developments in different fields. The plural nature of the “legacies” is stressed throughout, and has multiple dimensions: disciplinary, political, and even geographical given the “migration” of Spencerian theories all over the world.

正如这一文集的复数形式的标题所暗示的那样,斯宾塞的遗产是多重的。而且这些遗产可能是通过多个不同领域的后续发展传递给我们的。对“legacies”复数性质的强调贯穿本书首尾,并具有多个不同维度:学科维度、政治维度、甚至还有地理维度(因为斯宾塞的理论曾在全世界“迁移”)。

Sometimes, however, by looking far away you disregard what you have nearby. Bernard Lightman, for example, focuses his essay “Spencer’s British Disciples” on Beatrice Potter Webb and Grant Allen, quickly dismissing Auberon Herbert as a not very influential British disciple of Spencer.

不过,有些时候,由于过于关注远方,你会忽视眼前事物。比如,Bernard Lightman在他的文章“斯宾塞的英国门徒”中,主要聚焦于Beatrice Potter Webb和Grant Allen,却急匆匆地略过了Auberon Herbert,视其为斯宾塞的一位影响不大的英国门徒。

There might be a problem here: the influence the disciples themselves had may have to be disentangled from the thinking of the disciples

qua disciples. Lightman presents in fascinating and plentiful detail the most interesting paths of Webb and Allen, who both turned socialist to the disappointment of the master.

这里可能有个问题:这些门徒自身所具有的影响力,可能必须和身为门徒的他们的思想区分开来。Lightman以引人入胜和细节丰富的方式为我们介绍了Webb和Allen所走过的最为有趣的道路。他们俩都转变成了社会主义者,令其师父大失所望。

It would be hard to overemphasize the emotional nature of the relationship between Webb and Herbert Spencer. He was a family friend and a confidant of Laurencina Potter, Beatrice Potter Webb’s mother. A solitary man, Spencer bestowed unlimited affection on his dear friends’ kids.

Webb和赫伯特·斯宾塞之间的情感再怎么强调都不为过。斯宾塞是Webb一家的世交,是Beatrice Potter Webb的母亲Laurencina Potter的知己。未曾娶妻的斯宾塞将无限的情感倾注于他这位密友的孩子身上。【

编注:Beatrice Potter Webb是著名经济学家,伦敦经济学院和费边社的核心成员,这两个机构也是20世纪初英国社会主义运动的主要推动者。】

Young Beatrice grew up thinking that he was her best ally and the only adult truly interested in her intellectual development. Spencer, as Webb later wrote, pressed her “to become a scientific worker” and to a certain extent he became a model, for the “continuous concentrated effort in carrying out, with an heroic disregard of material prosperity and physical comfort, a task which he believed would further human progress.”

小Beatrice在成长过程中一直把斯宾塞当成最好的伙伴,认为他是唯一真正对她的智识进步感兴趣的成年人。如Webb后来所写的那样,是斯宾塞敦促她“成为一个科学工作者”,而他在某种程度上已然是一个典范,因为,“为了实施一项他认为能够推动人类进步的事业,他能持续集中地努力,为此奋而不顾物质财富和生理舒适。”

In her 1926 memoir

My Apprenticeship, Webb described at length the old friend, in a portrait very familiar to modern readers. She saw in him “the mental deformity which results from the extraordinary development of the intellectual faculties joined with the very imperfect development of the sympathetic and emotional qualities.”

在其1926年的回忆录《我的学徒生涯》中,Webb花大量笔墨描绘了这位老朋友,其形象现代读者非常熟悉。她在他身上看到“一种精神上的畸形,它是智识能力非凡发达与同情和情感极度不完善两相结合的产物。”

Webb’s Spencer is a human being obsessed with rationality and purpose who paid the price on the affective side. Though Webb is not stingy of kind words or affectionate recollections, it is hard not to speculate that her portrait of Spencer evokes magnificently all she disliked in unregulated capitalism: a purported organizational efficiency with little humanity to spare for those who are needy.

Webb眼中的斯宾塞是个痴迷于理性和目的,并为此在情感方面付出相应代价的人。尽管Webb并不吝啬写出赞誉之词或深情回忆,我们仍很难不这样推测:她对斯宾塞的描绘极好地再现了她对毫无限制的资本主义——一种对匮乏者冷酷无情的所谓的组织化效率——的所有憎恶。

It is indeed true that Spencer was the one who, as Lightman writes, “originally taught” Beatrice Webb “to value the scientific method and to think about social issues from a scientific perspective.” One wonders, however, exactly how much of Spencer’s insights she kept in her later thinking.

毫无疑问,如Lightman所写的那样,正是斯宾塞“最初教导”Beatrice Webb去“重视科学方法,并从一种科学的视角来考虑社会问题”。不过,人们不禁会怀疑,在她后来的看法中到底保留有多少斯宾塞的观点。

As for Auberon Herbert, certainly a less grand figure, he was an advocate of a libertarianism “that verged on anarchism,” in Taylor’s words. Reading Spencer was for him a truly life-changing experience. It made him lose “faith in the great machine” of politics and convinced him to become an apostle of freedom. Herbert’s libertarian anarchism is one of the “legacies” Michael Taylor examines in his essay.

至于Auberon Herbert,相较而言当然没那么出名。用Taylor的话说,他鼓吹的是一种“接近于无政府主义”的自由意志主义。阅读斯宾塞对他来说确实是真正改变人生的一种体验,让他丧失了对于政治“这台大机器的信念”,并说服他成为了一位传播自由的使徒。Herbert的自由意志论无政府主义是Michael Taylor在其文章中检视的多重“遗产”中的一种。

He approaches Spencer as a historian of political thought. The Taylor chapter, on the one hand, presents

Social Statics as a text that inspired multiple legacies, including the work of Henry George (who resented the fact that Spencer wanted the 1892 revised edition of this 1851 work to leave out the original chapter on land) and Piotr Kropotkin.

Taylor以一种政治思想史家的方式讨论斯宾塞。他所写作的那一章,一方面将《社会静力学》呈现为一份激发了多重遗产的文本,其中包括Henry George(斯宾塞要求《社会静力学》1892年修订版删除1851年原版中论土地一章,George对这一做法感到非常不满)和Piotr Kropotkin的著作。【

编注:Henry George是乔治主义改革运动的创始人,该运动最初主张以单一土地税代替其他所有税种,以便削弱地租收益而提高其他创造性活动的激励,但后来一些追随者将其改造成了土地国有化再分配主张。】

Taylor stresses how Spencer goes for voluntary and spontaneous arrangements, not necessarily for institutional settings based on the price system. But this won’t sound particularly controversial or new to libertarians, who, despite the caricature often made of them, understand that not everything in life is tradable at a money price. Their point is more subtle (and Spencerian): that is, top-down government intrusions may retard or altogether stop the spontaneous evolution (or adaptation to new circumstances) of human societies.

Taylor强调了斯宾塞支持自愿和自发的安排,而不一定支持基于价格体系的制度设置的做法。但这对于自由意志主义者来说,并不会特别富于争议或新颖,因为尽管他们经常在这一点上遭到夸张嘲弄,但他们知道并非生命中的每样事物都可以用某种货币价格进行交换。他们的观点更精致(也更斯宾塞式):即,从上至下的政府干预可能会妨碍或完全阻止人类社会的自发进化(或对新环境的适应)。

On the other hand, Taylor puts in context Spencer’s later, famous polemics against an intrusive state. The articles included in

The Man Versus the State were by and large a reaction to the “drift to the left” of William Gladstone’s 1880 government. Taylor emphasizes that “although Liberals were always suspicious of an overextended sphere of state action, the prevalent attitude was one of wariness of government overreach rather than an outright opposition to a positive role for the state.”

在另一方面,Taylor又结合语境分析了斯宾塞晚年反对干预性国家的著名论战文章。收在《人与国家》一书中的文章大体上都是针对1880年威廉·格莱斯顿政府“左倾转向”而发的反对。Taylor强调说:“尽管自由派历来对都国家行动范围的过度扩张心怀疑虑,但当时的流行观点只是对政府的过度扩张保持警惕,并不直接反对国家扮演积极角色。”

In other words, Spencer belonged to a minority of truly committed minimal government types that was never hegemonic in the intellectual realm, let alone in the pragmatic world of politicians. Fair enough, though the younger Spencer certainly saw himself as surrounded by writers with ideas rather close to his, particularly after the abolition of the Corn Laws.

换句话说,斯宾塞属于真正信奉最小政府的少数派,这种人在知识界从未成为主流,更不用说在政客们所处的实务世界。这说得很对,不过,青年斯宾塞当然认为自己周围有许多作家持有近似于己的观点,特别是在《谷物法》废除以后。

But the opposite is also true. Many critics have used against Spencer the same argument they later employed against Hayek’s

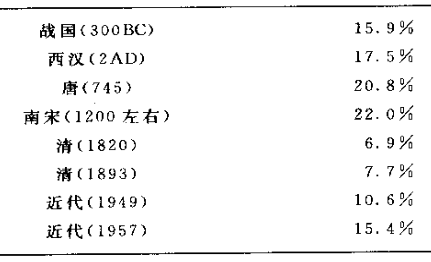

The Road to Serfdom: namely, that pointing to the slippery slope of state interventionism was ridiculous given that government was pursuing just limited (particularly in Spencer’s times) and benevolent interventions. In the 1870s, government spending was less than 10 percent of the British GDP—but increased rapidly in the new century.

然而,反对斯宾塞的也大有人在。许多批评者在反对斯宾塞时已经用到了他们后来用于反对哈耶克《通往奴役之路》的同一论证:即,认为国家干预主义会急剧膨胀恶化是可笑的,因为政府所追求的只是有限的(在斯宾塞的时代尤其如此)、善意的干预。在1870年代,政府支出还不到英国GDP的10%——尽管在接下来的新世纪里增长迅速。

One of the many take-aways of this book is that Spencer was a far more complex thinker than those who only know him as a diabolical “social Darwinist” may believe. Its essays might, for example, open the eyes of those who still have in mind the Herbert Spencer largely manufactured in the 1940s by Richard Hofstadter in

a book that made history as a beautifully written and yet quite misleading tirade.

本书的诸多简便结论之一是,作为一位思想家,斯宾塞非常复杂,远超那些只知他是个凶恶的“社会达尔文主义者”的人心中所想。比如,有些人心目中的斯宾塞仍是由理查德·霍夫斯塔特写于1940年代的一本书(该书将历史编成一份整齐漂亮但却颇为误人子弟的长篇檄文)所塑造【

译注:指《美国思想中的社会达尔文主义》一书】,而本书所收论文可以让这些人大开眼界。

Taylor explains that Spencer never thought that “social existence involved an unrelenting struggle for survival in which the richest were the most successful and the poor should go to the wall.” He quotes

Thomas Leonard’s important study on the Hofstadterian myth.

Taylor引用Thomas Leonard对“霍夫斯塔特迷思”的重要研究解释说,斯宾塞从未认为“社会存在中包含一种永不休止的生存斗争,在这场斗争中,最富裕的人就是最成功的,而最贫穷的人就应该碰壁失败。”

Jonathan H. Turner explains Spencer’s view of evolution as a process of continuous differentiation, which entailed at the same time more interdependence among the parts of the “social organism” and the need for a flexible regulation that allows for ever further differentiation and specialization. The pace of civilization, so to say, is limited by the extent of the division of labor.

Jonathan H. Turner将斯宾塞的进化观解释为一种持续分化的进程,而这就意味着“社会有机体”各个部分之间更大程度的相互依赖,而同时也要求实施弹性管理,以允许更进一步的分化和特化。可以说文明的步伐是受限于劳动分工水平。

Francis, who like his co-editor cites the Leonard monograph, also makes clear Spencer’s commitment to pacifism: “Spencerians believed that imperial conquest might have been a natural phenomenon when employed by ancient states, but was an archaic activity in modern times” and a most immoral one. The thread running through all of Spencer’s works is the idea that society progresses toward the minimization of violence, which had been needed at earlier stages of civilization.

Francis跟共同主编Taylor一样引用了Leonard的论文,也明确指出了斯宾塞对和平主义的信奉:“斯宾塞主义者相信,当帝国征服发生于古代国家手中时,它们也许是种自然现象,但在现时代,它就是一种过时的活动”,同时也是最不道德的活动之一。贯穿斯宾塞所有著作的一条主线就是这样一种观念:暴力在文明的最初阶段是需要的,但社会进步的方向就是暴力的最小化。

This book may convey a sense of Spencer’s true understanding of complexity. In the last pages of

Social Statics, which revolves around the idea of betterment and progress, he explains that “the institutions of any given age exhibit the compromise made by these contending moral forces at the signing of their last truce.” His magnificent

The Study of Sociology (1873) would be a relevant work for those interested in the proper role of the social sciences and their limits, if only they read it.

本书可能向我们传达了一些斯宾塞对于复杂性的真正理解。在《社会静力学》的最后部分,斯宾塞讨论的是改良与进步。他解释说,“任何给定时代的制度都呈现出妥协,这些妥协是彼此竞争的道德力量在签订最终停战协定时所达成的。”对于那些对社会科学的恰当角色及其局限所在感兴趣的人来说,斯宾塞的皇皇巨著《群学肆言》(1873)很值得关注,当然前提是你能读一读。

Turner’s essay, possibly the most thorough in this collection, claims Spencer’s centrality in the development of sociology. Turner is sure that Spencer was “a theorist, not in the often sloppy and vague social theory sense, but in the hard-science view of theory as a series of abstract laws that explain the operation of some portion of the universe.” Unfortunately, he writes, though “many of his ideas have endured, . . . most people do not know that they come from Spencer, so ingrained is the avoidance of anything Spencerian.”

Turner的文章可能是这本文集中最为深入的,它认为斯宾塞在社会学的发展过程中占据中心位置。Turner认定斯宾塞是“一位理论家,这里所说的理论不是社会理论意义上的那种很马虎或含糊的理论,而是表现为一系列抽象规则、能够解释宇宙某一部分之运转的那种硬科学意义上的理论。”不幸的是,他写道,尽管“他的许多观点延续不朽……绝大多数人并不知道它们来自斯宾塞。对任何斯宾塞主义的东西都避而不谈的做法是如此顽固。”

Turner signals, for example, that Spencer had a very perceptive and thorough vision of power and the dynamics of the mobilization of coercive resources, which also anticipates the analysis of political elites by Vilfredo Pareto (not by chance, an avid reader of Spencer’s).

比如,Turner表明,斯宾塞对于权力和强制性资源的动员过程持有一种认知透彻、细察入微的理解,这也早于维弗雷多·帕累托对于政治精英的分析(帕累托是斯宾塞的热心读者,这并非偶然)。

Spencer’s dichotomy of militant and industrial societies is not the naive teleology many assumed. “Militant societies are always centralized because they must deal with conflict and war, whereas” industrial societies “are not centralized and allow individuals and corporate units considerable freedom of activity.” Nations may go in one direction or another, depending on many factors.

斯宾塞对于军事社会和工业社会的二分并不是许多人所理解的那种幼稚的目的论。“军事社会总是中央集权的,因为它们必须应付冲突和战争”,而工业社会“并不中央集权,并允许个体和团体拥有可观的行动自由。”国家可能走向完全不同的方向,这取决于许多不同因素。

Spencer learnt it the hard way. His alleged “drift to conservatism,” or the fact that the tone of his articles and political pamphlets got drier, is due to his understanding of developments in England, which he considered revealed a resurgence of the militant spirit.

斯宾塞是历经艰难困苦才得出这一观点的。他那被指为“保守主义转向”的转变,以及他的文章和政论日益冷峻这一事实,源自他对于英国内部变化的理解。他认为这种变化表明了军事精神的复活。

If I had any quibble about this impressive collection, it would be that the propensity to consider

The Man Versus the State as “just” a political pamphlet causes the contributors to overlook that this is perhaps the first work whose arguments are truly centered around the notion of unintended consequences. All in all, though,

Herbert Spencer: Legacies may foster a better understanding of this seminal thinker and raise yet more interest in his underappreciated writings.

如果说我对这本令人印象深刻的文集还有什么挑剔的话,那就是作者们将《人与国家》仅仅视作一本政论册子的倾向导致他们忽视了一点:它可能是第一本真正集中围绕“非意图后果”这一概念进行论证的书籍。总而言之,《赫伯特·斯宾塞:遗产》可能增进我们对这位重要思想家的更好理解,同时进一步增加人们对于他的那些明珠蒙尘之作的更大兴趣。

(编辑:辉格@whigzhou)

*注:本译文未经原作者授权,本站对原文不持有也不主张任何权利,如果你恰好对原文拥有权益并希望我们移除相关内容,请私信联系,我们会立即作出响应。

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

订阅

订阅