【2016-02-16】

@whigzhou: 个人主义必定伴随着对抗性,否认对抗、讲究隐忍退让、一团和气、齐心协力拧成一股绳、为此诉诸权威以压制对抗、抹除差异的群体,无论是家庭还是社会,都是容不下个人主义的,我们不能在提倡个人主义的同时否认对抗,而只能在承认对抗的同时设法学会以诚实、体面、守信、有尊严的方式处理对抗。

@whigzhou: 至于从何时开始、在何种程度上将孩子作为独立自主的个人对待,我的看法是分年龄段逐步推进,并鼓励孩子证明自己已配得上更高一级的对待,最终在(more...)

【2016-02-16】

@whigzhou: 个人主义必定伴随着对抗性,否认对抗、讲究隐忍退让、一团和气、齐心协力拧成一股绳、为此诉诸权威以压制对抗、抹除差异的群体,无论是家庭还是社会,都是容不下个人主义的,我们不能在提倡个人主义的同时否认对抗,而只能在承认对抗的同时设法学会以诚实、体面、守信、有尊严的方式处理对抗。

@whigzhou: 至于从何时开始、在何种程度上将孩子作为独立自主的个人对待,我的看法是分年龄段逐步推进,并鼓励孩子证明自己已配得上更高一级的对待,最终在(more...)

【2016-04-16】

@whigzhou: 个人禀赋可遗传性,社会阶梯对个人禀赋的选择,择偶的同质化倾向,阶层内婚,阶级分化,族群禀赋差异化,地区经济分化,大国-单一民族国家-城邦小国的根本区别……,把Charles Murray,Garett Jones和Gregory Clark的工作合起来看,貌似就通了,有关社会演化和长期经济表现的一幅新图景呼之欲出。

@whigzhou: 这几年我在经济问题上经历了一次思想转变,越来越相信culture matters, genetic matters,在写作《自私的皮球》时,我基本上还是个制度主义者,虽然也相信文化重要,但(more...)

Cereals, appropriability, and hierarchy

谷物、可收夺性和等级制

作者:Joram Mayshar, Omer Moav, Zvika Neeman, Luigi Pascali @2015-9-11

译者:Luis Rightcon(@Rightcon)

校对:沈沉(@你在何地-sxy)

来源:VoxEU,http://www.voxeu.org/article/neolithic-roots-economic-institutions

Conventional theory suggests that hierarchy and state institutions emerged due to increased productivity following the Neolithic transition to farming. This column argues that these social developments were a result of an increase in the ability of both robbers and the emergent elite to appropriate crops. Hierarchy and state institutions developed, therefore, only in regions where appropriable cereal crops had sufficient productivity advantage over non-appropriable roots and tubers.

传统理论认为,等级制和国家产生的缘由在于:人类在新石器时代农业转向时出现了生产率增长。而本专栏则指出,上述社会发展是掠夺者和新生的精英分子收夺谷物的能力上升的结果。因此,仅仅是在那些易于收夺的谷物比其他不易收夺的块根和块茎作物在产量上拥有充分优势的地区,才会产生等级制和国家。

What explains underdevelopment?

欠发达的原因是什么?

One of the most pressing problems of our age is the underdevelopment of countries in which government malfunction seems endemic. Many of these countries are located close to the Equato(more...)

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

Hive Mind

蜂巢思维

作者:Robin Hanson @ 2015-11-13

译者:Veidt(@Veidt)

校对:龟海海

来源:overcomingbias.com,http://www.overcomingbias.com/2015/11/statestupidity.html

Some people like murder mystery novels. I much prefer intellectual mysteries like that in Garett Jones’ new book Hive Mind: How Your Nation’s IQ Matters So Much More Than Your Own:

有些人喜欢看谋杀悬疑小说,而我则更青睐那些智力悬疑类著作,例如Garett Jones的新书《蜂巢思维:为什么你们国家的整体智商水平甚至比你自己的智商还要重要》中所描述的:

Over a decade ago I began my research into how IQ matters for nations. I soon found that the strong link between average IQ and national productivity couldn’t be explained with just the conventional finding that IQ predicts higher wages. IQ apparently mattered far more for nations than for individuals.

在十年前我开始研究智商对国家意味着什么。我很快就发现,国民的平均智商与国家生产率之间的强相关性,并不能以高智商预示着高薪资这一传统发现来解释。智商对国家的作用显然比对个人重要得多。

In my early work, I estimated that IQ mattered about six times more for nations than for individuals: your nation’s IQ mattered so much more than your own. That puzzle, that paradox of IQ, is what set me on my intellectual journey. …

在我早期的研究中,我曾经做过一个估测,智商对国家所发挥的作用要比对于个人所发挥的作用高大约6倍,也就是说:你所在国家的平均智商水平比你自己的智商水平要重要的多。这个谜题,或者叫“智商悖论”,让我踏上了这条智力探索的漫漫长路…

I’ll lay out five major channels for how IQ can pay off more for nations than for you as an individual:

我将在下面列举五个方面的依据说明智商对国家的(more...)

Over a decade ago I began my research into how IQ matters for nations. I soon found that the strong link between average IQ and national productivity couldn't be explained with just the conventional finding that IQ predicts higher wages. IQ apparently mattered far more for nations than for individuals. 在十年前我开始研究智商对国家意味着什么。我很快就发现,国民的平均智商与国家生产率之间的强相关性,并不能以高智商预示着高薪资这一传统发现来解释。智商对国家的作用显然比对个人重要得多。 In my early work, I estimated that IQ mattered about six times more for nations than for individuals: your nation’s IQ mattered so much more than your own. That puzzle, that paradox of IQ, is what set me on my intellectual journey. … 在我早期的研究中,我曾经做过一个估测,智商对国家所发挥的作用要比对于个人所发挥的作用高大约6倍,也就是说:你所在国家的平均智商水平比你自己的智商水平要重要的多。这个谜题,或者叫“智商悖论”,让我踏上了这条智力探索的漫漫长路... I’ll lay out five major channels for how IQ can pay off more for nations than for you as an individual: 我将在下面列举五个方面的依据说明智商对国家的影响要远远超出对个人的影响: 1. High-scoring people tend to save more, and some of that savings stays in their home country. More savings mean more machines, more computers, more technology to work with, which helps make everyone in the nation more productive. 1. 高智商的人更会储蓄,而其中的部分储蓄将留在他们的母国。更多储蓄意味着更多的机器,更多电脑,更多可运用的技术,而这些都能帮助生活在这个国家的所有人变得更有效率。 2. High-scoring groups tend to be more cooperative. And cooperation is a key ingredient for building higher-quality governments and more productive businesses. 2. 高智商的群体倾向于更具合作性。而合作则是建设更高质量的政府和更高效企业的一个关键因素。 3. High-scoring groups are more likely to support market-oriented policies, a key to national prosperity. People who do well on standardized tests also tend to be better at remembering information, and informed voters are an important ingredient for good government. 3. 高智商的人群更倾向于支持亲市场政策,这是国家繁荣的关键。那些在标准智商测试中得分更高的人同样也在记忆信息方面拥有优势,而博闻多识的选民是构建良好政府的重要因素。 4. High-scoring groups will tend to be more successful at using highly productive team-based technology. With these “weakest link” technologies, one misstep can destroy the product’s value, so getting high-quality workers together is crucial. Think about computer chips, summer blockbuster films, cooperative mega-mergers. 4. 高智商的人群在使用那些高效的基于团队协作的技术上要做得更好。在这些“最弱一环”【编注:Weakest Link是BBC二台的一档竞赛游戏节目,参赛者需一环扣一环的连续正确解答问题,以最终赢得奖金,每一回合过后,参赛者互相投票选出该回合的“最弱一环”,当选者出局离场。】技术中,任何一步差错都可能会毁掉整个产品的价值,所以让高素质工人进行协作至关重要。想想那些电脑芯片,夏季震撼的电影大片,还有巨型公司的兼并,都是此类协作的产物。 5. The human tendency to conform, at least a little, creates a fifth channel that multiplies the effect of the other four: the imitation channel, the peer effect channel. Even a small tendency to conform, to act just a little bit like those around us, too try to fit in, tends to quietly shape our behavior. If you have cooperative, patient, well-informed neighbors, that probably makes you a bit more cooperative, patient, and well-informed. 5. 人类多少有一点顺从倾向,这创造出了能够放大上述四类作用的第五种效应:那就是模仿效应,或“伙伴效应”。即使是很小一点顺从倾向,也就是行动得更像我们身边的人一些,或者说试图适应身边的人,都很可能在潜移默化中塑造我们的行为。如果你拥有富于合作性,有耐心而且博闻多识的邻居,那么这可能也会让你也变得更有合作性,更耐心,也更博闻多识。 Of course, test scores don’t explain everything about the wealth of nations: I’m only claiming that IQ-type scores explain about half of everything across countries – and much less within a country.当然,智力测试得分无法解释关于国家富裕程度的一切:我只是说智商类测试得分能够解释国家间大约一半的财富差异——而对一个国家内部的差异,它能解释的部分则要小得多。 The question of why IQ matters more for nations than individuals does indeed seem quite important, and quite puzzling, and Jones is to be praised for his readable and informative book calling it to our attention. And the five explanations Jones offers are indeed, as he claims, channels by which each of us benefits from the IQ of the people around us. 为什么智商对于国家的影响相比对个人的影响要大得多这个问题看来的确很重要,而且也着实是个谜,因此我认为本书作者Jones应该为他这部兼具可读性和信息量并让我们充分意识到这个问题的著作而获得称赞。如他所言,上面所提到的五种解释的确都是我们受益于自己身边人群智商的渠道。 However (you knew that was coming, right?), when we benefit from the IQ of people nearby who are within the scope of shared social institutions, then institution access prices can reflect these benefits. For example, employers can pay more for a smart employee who is not only more productive personally, but also raises the productivity of co-workers. Landlords can offer lower rents to people that other renters want to be near. Stores can offer discounts to customers that other customers like nearby when they are shopping. And clubs can offer discounts to entice memberships from those with which others like to associate. 然而(你知道我会这么说的,对吧?),当我们在共享社会机构的范围内从身边人群的智商中受益时,这些机构的准入价格便可体现这种益处的大小。例如,雇主可以为一名不仅自己生产率高,而且还能提升同事生产率的雇员发放更多的工资。土地主可以向其他租户都愿意靠近的那家租户收取更低的地租。商店可以向那些在购物时有很多人愿意接近的顾客提供折扣价格。而俱乐部也可以通过向那些其他人都愿意结交的人提供折扣来吸引他们成为自己的会员。 So simple economic theory leads us to expect that the benefits that smart people give to others nearby, within these shared priced-entry institutions, will be reflected in their incomes. 因此简单的经济理论便可让我们得出这样的预期,那些聪明人通过共享一个有偿准入的机构而带给身边人的好处,将最终反映在他们的收入上。 Specifically, people can plausibly pay more to live, club, shop, and work near and influenced by others who are more patient, cooperative, informed, and reliable. So these local benefits of smart associates do not plausibly explain the difference between how individual and national IQ correlate with income. 具体地说,人们完全可以花更多钱以换取生活在这些更有耐心,更富合作性,更博闻多识,也更可靠的人身边,在其附近购物,参与社团活动,并受其影响完全。所以这些聪明的被结交者们为身边人带来的局部收益,并不能合理地解释个人智商与收入的相关性为何不同于与国家平均智商与收入之间的相关性。【编注:意思是,假如高智商个体能够以本节所述方式将其带给身边人的利益(一种正外部性)内化为私人收入,这一相关性差别就不会存在。】 To explain this key difference (a factor of six!) we need big market or government failures. These could result if: 想要解释这一关键差异(第六个因素!),我们需要看看大市场或者政府的失败。下面几个原因可能导致这样的结果:

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

【2016-03-07】

@Ent_evo 一个理科生对三八劳动妇女节的杂感 http://t.cn/Rw3aI8T

@Ent_evo: 转眼一年了,好像也没有什么变化

@whigzhou: “为“男性掌控资源”这一现状公开辩护的人,通常绕来绕去总会绕到生物属性上面……这恐怕并不是最重要的理由,但这应该是唯一还能拿出来说说而不被骂成狗的理由了”——为什么需要辩护?若一种现状并非强制或权利缺失的结果,它就不需要辩护

@whigzhou: 或者说,选择自由就是充分的辩护理由

@whigzhou: 比如一种(more...)

Whose Fault is Baltimore?

巴尔的摩骚乱谁之过?

时间:@ 2015-4-30

译者:Drunkplane(@Drunkplane-zny)

校对:龟海海

来源:The Burning Platform,http://www.theburningplatform.com/2015/04/30/whose-fault-is-baltimore/

I’ve seen the liberal lying MSM pondering how WE could allow the riots, looting, burning and lawlessness to happen, as if it is our collective fault. Obama stands before his teleprompter and pontificates about the need for us to end the poverty that supposedly led to Purge Night in Charm City.

我看到那些满嘴跑火车的自由派主流媒体成天思考我们(又被代表)怎么能容忍暴动、抢劫、纵火和无法无天,就好像这是整个城市的错。奥巴马站在他的提词器前武断地宣称消除贫困的必要,似乎这贫困将会导致“净化之夜”在这魅力之城上演。【译注:电影《净化》中,未来的美国变成了一个极权的警察国家。每年的3月21日晚7点到次日早7点被称作净化之夜,在此期间所有的暴力犯罪都是合法的。】

That term cracks me up. The city has so much charm, its football team once snuck out of town overnight and headed to Indianapolis. It has so much charm its baseball team was forced to play a game with no fans in the stands.

这情景让我反胃。这座城市是如此有魅力,它的橄榄球队曾半夜溜出城跑到印第安纳波利斯去;它如此有魅力,它的棒球队曾被迫在没有一个球迷的球场上打比赛。

I think most people can agree that Freddie Gray, a petty drug dealer, was killed in police custody for the crime of looking suspicious. The policemen who killed him d(more...)

“It’s a very delicate balancing act, because while we tried to make sure that they were protected from the cars and the other things that were going on, we also gave those who wished to destroy space to do that as well.” “(警方的行动)有一种微妙的平衡,因为当我们试图确保抗议者不被车流和其他来往的东西伤害的同时,也给了那些想要搞破坏的人以机会。”You reap what you sow America. 你们曾在美国大地播撒下那些种子,如今正在收获它们结出的果实。 (编辑:辉格@whigzhou) *注:本译文未经原作者授权,本站对原文不持有也不主张任何权利,如果你恰好对原文拥有权益并希望我们移除相关内容,请私信联系,我们会立即作出响应。

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

苍白无力的欧洲普世主义

Europe’s Bloodless Universalism

作者:Theodore Dalrymple @ 2015-11-19

译者:Veidt(@Veidt)

校对:Drunkplane(@Drunkplane-zny)

来源:Library of Law and Liberty,http://www.libertylawsite.org/2015/11/19/europes-bloodless-universalism/

By now the story of Omar Ismail Mostefai, the first of the perpetrators of the Paris attacks to be named, is depressingly familiar. One could almost have written his biography before knowing anything about him. A petty criminal of Alger(more...)

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

Imperial exams and human capital

科举考试与人力资本

作者:Stephen Hsu @ 2015-5-20

译者:Luis Rightcon(@Rightcon)

校对:沈沉(@你在何地-sxy)

来源:Information Processing,http://infoproc.blogspot.com/2015/05/imperial-exams-and-human-capital.html

The dangers of rent seeking and the educational signaling trap. Although the imperial examinations were probably g loaded (and hence supplied the bureaucracy with talented administrators for hundreds of years), it would have been better to examine candidates on useful knowledge, which every participant would then acquire to some degree.

寻租的危险和教育信号陷阱。尽管科举考试基于一般智力因素(因此几百年来为官僚机构输送了很多优秀的行政人员)【校注:G因素,或一般智力因素,心理学上指人类一切认知活动都依赖的智力因素】,但如果它考察的是候选者的实用知识,那会更好,这样每个候选者都可以对这种知识有所掌握。

See also Les Grandes Ecoles Chinoises and History Repeats.

另请参考我的博文:“中国大学”和“历史在重复”

(more...)Farewell to Confucianism: The Modernizing Effect of Dismantling China’s Imperial Examination System Ying Bai The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology 这里是香港科技大学Ying Bai的论文“告别儒家:中国废除科举制度的现代化影响” Imperial China employed a civil examination system to select scholar bureaucrats as ruling elites. This institution dissuaded high-performing individuals from pursuing some modernization activities, such as establishing modern firms or studying overseas. This study uses prefecture-level panel data from 1896-1910 to compare the effects of the chance of passing the civil examination on modernization before and after the abolition of the examination system. 中华帝国采用科举考试制度筛选士大夫来作为统治精英。这一机制阻止了优秀的个人从事一些现代化的活动,如建立现代企业或者去海外学习。本研究使用了从1896年到1910年废科举前后的府级名册数据,来考察科举晋身机会对现代化的影响。 Its findings show that prefectures with higher quotas of successful candidates tended to establish more modern firms and send more students to Japan once the examination system was abolished. As higher quotas were assigned to prefectures that had an agricultural tax in the Ming Dynasty (1368-1643) of more than 150,000 stones, I adopt a regression discontinuity design to generate an instrument to resolve the potential endogeneity, and find that the results remain robust. 研究结果表明,废科举之后,那些科举取士配额较多的府建立的现代企业更多,向日本派遣的留学生也更多。由于那些在明朝时期(1368-1643)缴纳农业税超过15万石的府拥有的取士配额更多,我采用断点回归方法生成了一种工具,以解决潜在的内生相关性问题,发现结果依然稳固。【校注:此为论文“摘要”】From the paper: 论文内容摘录:

Rent seeking is costly to economic growth if “the ablest young people become rent seekers [rather] than producers” (Murphy, Shleifer, and Vishny 1991: 529). Theoretical studies suggest that if a society specifies a higher payoff for rent seeking rather than productive activities, more talent would be allocated in unproductive directions (Acemoglu 1995; Baumol 1990; Murphy, Shleifer, and Vishny 1991, 1993). 对于经济增长来说,寻租行为代价非常昂贵——如果“最优秀的年轻人倾向于成为寻租者,而不是生产者” (Murphy, Shleifer, and Vishny 1991: 529) 的话。理论研究表明,如果社会让寻租行为比生产行为获利更多的话,更多有才能的人将会被分配到不事生产的方向(Acemoglu 1995; Baumol 1990; Murphy, Shleifer, and Vishny 1991, 1993)。 This was the case in late Imperial China, when a large part of the ruling class – scholar bureaucrats – was selected on the basis of the imperial civil examination. The Chinese elites were provided with great incentives to invest in a traditional education and take the civil examination, and hence few incentives to study other “useful knowledge” (Kuznets 1965), such as Western science and technology.2 Thus the civil examination constituted an institutional obstacle to the rise of modern science and industry (Baumol 1990; Clark and Feenstra 2003; Huff 2003; Lin 1995). 这就是中华帝国晚期的情况,统治阶级的很大一部分——即士大夫们——以科举考试的形式选拔出来。中国的精英们具有极大的激励来投资于传统教育,并且参加科举考试,因此对于其他“实用知识”就不那么热情了(Kuznets 1965),比如说西方科学技术。这样,科举考试就构成了现代科学技术发展的制度性障碍(Baumol 1990; Clark and Feenstra 2003; Huff 2003; Lin 1995)。 This paper identifies the negative incentive effect of the civil exam on modernization by exploring the impact of the system’s abolition in 1904-05. The main empirical difficulty is that the abolition was universal, with no regional variation in policy implementation. To better understand the modernizing effect of the system’s abolition, I employ a simple conceptual framework that incorporates two choices open to Chinese elites: to learn from the West and pursue some modernization activities or to invest in preparing for the civil examination. 本文通过探索1904-1905年间废除科举考试的影响,来鉴别科举考试对于现代化的负面激励效应。主要的实证困难在于这一废除举动是全国性的,没有政策实施上的地区差异。为了更好地理解废除科举体制对于现代化建设的影响,我采用了一个简单的概念框架,其中包括了中国精英们在当时的两个选项:向西方学习并实行一些现代化举动,或是为准备科举考试而增加投入。 In this model, the elites with a greater chance of passing the examination would be less likely to learn from the West; they would tend to pursue more modernization activities after its abolition. Accordingly, the regions with a higher chance of passing the exam should be those with a larger increase in modernization activities after the abolition, which makes it possible to employ a difference-in-differences (DID) method to identify the causal effect of abolishing the civil examination on modernization. 在这个模型中,那些更有可能通过科举考试的精英们将不太可能向西方学习;而废除科举后他们将倾向于更多进行现代化活动。于是,科举晋身机会更大的地区应当也是那些废除科举之后现代化活动更为活跃的地区,这就使得我可以采用双重差分(DID)方法来鉴别废除科举制对于现代化的因果效应。 I exploit the variation in the probability of passing the examination among prefectures – an administrative level between the provincial and county levels. To control the regional composition of successful candidates, the central government of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) allocated a quota of successful candidates to each prefecture. In terms of the chances of individual participants – measured by the ratio of quotas to population – there were great inequalities among the regions (Chang 1955). 我利用了不同府在科举通过率上的差异——“府”这一地方的管理层级介于省级和县级之间。为了控制中选者的地域构成,清王朝(1644-1911)把取士名额分配到府。以个人投考者的成功率衡量——以配额占总人口比率计——不同地区很不平均(Chang 1955)。 To measure the level of modernization activities in a region, I employ (1) the number of newly modern private firms (per million inhabitants) above a designated size that has equipping steam engine or electricity as a proxy for the adoption of Western technology and (2) the number of new Chinese students in Japan – the most import host country of Chinese overseas students (per million inhabitants) as a proxy of learning Western science. Though the two measures might capture other things, for instance entrepreneurship or human capital accumulation, the two activities are both intense in modern science and technology, and thus employed as the proxies of modernization. ... 为衡量某个地区的现代化活动水平,我采用了(1)新成立的、具有一定规模、并应用了蒸汽机或者电力的现代私企数量(每百万居民),来代表对于西方科技的应用情况;以及(2)(每百万居民中)新近去往日本的中国留学生数量(日本是中国海外留学生的最主要目的地),来代表对于西方科学的学习情况。虽然这两者可能都会捕捉到其他东西,比如企业家或者人力资本积累,但这两个活动在现代科学技术中都是非常剧烈的,所以可用于代表现代化进程……From Credentialism and elite employment: 以下摘自我之前的博文“文凭主义与精英雇佣”:

Evaluators relied so intensely on “school” as a criterion of evaluation not because they believed that the content of elite curricula better prepared students for life in their firms – in fact, evaluators tended to believe that elite and, in particular, super-elite instruction was “too abstract,” “overly theoretical,” or even “useless” compared to the more “practical” and “relevant” training offered at “lesser” institutions – but rather due to the strong cultural meanings and character judgments evaluators attributed to admission and enrollment at an elite school. I discuss the meanings evaluators attributed to educational prestige in their order of prevalence among respondents. ... 评价者们过于依赖于把“学校”作为评估的标准,这不是因为他们相信精英教育的内容可以使学生更善于应对公司生活——事实上,评价者倾向于相信,与“更差”的机构所提供的更“实用”和“更有意义”的训练相比,精英教育、特别是超级精英教育“太抽象”、“过于理论化”、甚或是“根本没用”——而是因为评价者给精英学校的招生录取赋予了丰厚的文化内涵和个性判断。我将按照它们各自在受访者中的流行程度次序,来讨论评价者在教育声望上所赋予的意义……(编辑:辉格@whigzhou) *注:本译文未经原作者授权,本站对原文不持有也不主张任何权利,如果你恰好对原文拥有权益并希望我们移除相关内容,请私信联系,我们会立即作出响应。

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

超越邓巴数#5:青春的躁动

辉格

2015年10月7日

当多个群体联合成为更大社会时,总是面临这样一个组织问题:如何将维持秩序和协调集体行动的权力集团的规模限制得足够小,以确保其紧密合作;在前面的文章里,我已介绍了几种方法:1)强化父权和宗族,以将权力限制在长辈手里,2)赋予长支与幼支以不平等地位,从而将权力集中在长支手里,3)通过婚姻关系的内聚化,形成上层姻亲联盟,并垄断权力。

后两种方法都意味着地位分化,然而,只有当权势能够跨代积累时,个体和支系间的权势差异才能固化成阶层,进而形成稳定牢固的权力集团;可继承的财产权恰好创造了这样的条件,但是,不同类型的财产权有着不同的积累特性,而后者限定了地位分化的可能性,从而将社会大型化引向不同方向。

早期农民的主要财产是土地和牲畜,在旧大陆的多数农业社会,种植和畜牧都以某种比例混合搭配;在跨代传承过程中,土地数量要恒定的多(尽管也会因土壤退化或河流改道等原因而变动),牲畜数量则波动很大,而且出于生产组织的考虑,人们在处置土地产权时,有着普遍的抗分割倾向,即便不得不分也会尽可能推迟,而畜群则很容易分割,事实上也总是一有机会就分割。

例如,蒙古游牧者的多妻家庭,每位妻子和她的孩子们拥有单独的帐幕和自己的畜群,构成独立家户,而约鲁巴宗族社区(规模常达数百人)的土地归宗族集体所有,核心家庭只拥有使用权,成员去世后就被收回重新分配,马里多贡人(Dogon)的多妻家庭则处于中间状态:土地由家庭集体所有,并由长妻带领诸妻共同耕种,而牲畜则由每位妻子分别拥有,类似情况在非洲农牧混业社会十分常见。

土地和牲畜的差异也体现在分割时机上,畜牧者往往在男孩成年时便分给他几头牲口,作为其建立自己畜群的启动资本,到他结婚时,再分走一群牲畜(否则就无法成家),所以,以畜牧为主业者,家产分割继承是随每个继承人结婚而逐次进行的,最后父母保留的那一份由幼子继承,相比之下,以种植为主业者,通常要等到大家长去世之后,或宗族裂变之际,才一次性分家,在采用长子继承制的社会,甚至在分家时,也只分牲畜(和其他动产)而不分土地。

由于畜产的固有分割倾向,很难跨代积累,每一代的财富差异很快被子女数量所抹平,这样,以牲畜为主要资产的社会就难以形成稳定的阶层分化,因而无法通过上述后两条途径实现大型化,结果,要么停留在碎片化状态(就像中亚游牧民在多数时候那样),要么必须找出其他途径,他们找到的方法之一,是(more...)

超越邓巴数#4:婚姻粘结剂

辉格

2015年9月29日

通过组织宗族和强化父权而扩展父系继嗣群,终究会因亲缘渐疏和协调成本剧增而遭遇极限,西非约鲁巴宗族社区和华南众多单姓村显示了,其规模最多比狩猎采集游团高出一两个数量级(几百到几千人),若要组织起更大型社会,便需要借助各种社会粘结剂,将多个父系群联合成单一政治结构,而婚姻是最古老也最常见的粘结剂。

婚姻的粘结作用,在前定居社会便已存在,列维-斯特劳斯发现,相邻的若干继嗣群之间建立固定通婚关系,以交表婚之类的形式相互交换女性,是初民社会的普遍做法;持久通婚维系了群体间血缘纽带,促进语言上的融合,共享文化元素,让双方更容易结盟共同对抗其他群体,即便发生冲突也比较容易协商停战,所有这些,都有助于它们建立更高一级的政治共同体。

此类固定结对通婚关系广泛存在于澳洲土著和北美印第安人中,其最显著特点是,它是群体本位而非个体本位的,缺乏定居者所熟悉的从个体出发的各种亲属称谓,有关亲属关系的词汇,所指称的都是按继嗣群(或曰氏族,常由图腾标识)、性别和辈份三个维度所划分出的一个组别,婚姻必须发生在两个特定组别之间。(值得留意的是:这种模式常被错误的称为“群婚制”,实际上,其中每桩婚姻都发生在男女个体之间,并非群婚。)

典型的做法是,两个父系群结对通婚,澳洲西北阿纳姆地的雍古人(Yolngu),20个氏族分为两个被人类学家称为半偶族(moiety)的组,每个半偶族的女性只能嫁到另一个半偶族;这确保了夫妻双方的血缘不会比一级表亲更近;周人姬姓与姜姓的持续频繁通婚,或许也是此类安排的延续;不那么系统化的交表婚则更为普遍,几乎见于所有古代社会。

以此为基础,还发展出了更复杂的结对安排,比如西澳的马图苏利纳人(Martuthunira)采用一种双(more...)

多布人没我们这么好;他们凶恶,他们是食人族!我们来多布时,十分害怕。他们会杀死我们。但看到我们吐出施过法术的姜汁,他们的头脑改变了。他们放下矛枪,友善的招待我们。当拜访船队接近对方岛屿时,他们反复念诵类似这样的咒语:

尔之凶恶消失,消失,噢,多布男人! 尔之矛枪消失,消失,噢,多布男人! 尔之战争油彩消失,消失,噢,多布男人! ……另一个故事则说明了在这种恐惧氛围中,拥有库拉伙伴的价值:一个叫Kaypoyla男人,航行中搁浅于一个陌生岛屿,同伴全部被杀死吃掉,他被留作下一顿美餐,夜晚侥幸逃出,流落至另一岛上,次日醒来发现自己被一群人围着,幸运的是,其中一位是他的库拉伙伴,于是被送回了家。 在特罗布里恩,一位酋长的地位很大程度上体现在众多妻子(常多达十几个)带给他的庞大姻亲网络上,通过与妻子兄弟的互惠交换,常积累起显示其权势的巨大甘薯库存,姻亲网络也让他在库拉圈中地位显赫,普通人一般只有几位库拉伙伴,而酋长则有上百位;人类学家蒂莫西·厄尔([[Timothy Earle]])也发现,在部落向酋邦的发展过程中,酋长们建立其权势地位的手段之一,便是通过精心安排婚姻来建立姻亲网络。 对于社会结构来说,重要的是,姻亲关系的上述作用,被宗族组织和父权成倍放大了,并且反过来强化了后两者;若没有紧密的宗族关系,一位男性从一桩婚姻中得到的姻亲就十分有限,岳父加上妻子的兄弟,但宗族的存在使得婚姻不仅是一对男女的联合,也是两个家族的联合,随着繁复婚姻仪式的逐步推进,双方众多成员的关系全面重组,并在此后的周期性节庆聚宴上得到反复强化,这也是为何在具有宗族组织的社会中,婚姻和生育仪式发展得那么繁杂隆重。 类似的,假如没有强父权,男性从婚姻中得到的姻亲数量,便主要取决于妻子数量,而在高度平等主义的前定居社会,多妻较少见,而且妻子数较平均(但也有例外,比如澳洲,但那里的高多妻率同样伴随着强父权和老人政治),但父权改变了姻亲性质,在控制了子女婚姻之后,长辈取代结婚者本人而成为姻亲关系的主导者,这样一来,一位男性能够主动建立并从中获益的姻亲关系,便大大增加了。 宗族和父权不仅拓展了个人发展姻亲的潜力,而且拉大了个体之间和家族支系之间社会地位的不均等;在游团一级的小型简单社会中,尽管个体境遇和生活成就也有着巨大差异,但这差异主要表现为后代数量,很少能积累起可以传给后代的资源,而现在,由于宗族使得姻亲关系成为两个家族的广泛结合,因而这一关系网成了家族支系的集体资产,而同时,由长辈安排子女婚姻,使得这一资产具有了可遗传性,这就好比现代家族企业在晚辈接班时,长辈会把整个商业关系网络连同有形资产一起传给他。 借助长辈所积累的资源,成功者的后辈从人生起步时便取得了竞争优势,这便构成了一种正反馈,使得父系群中发达的支系愈加发达,最终在群体内形成地位分化;这一分化也将自动克服我在上一篇中指出的父系群扩张所面临的一个障碍:当家长联盟向更高层次发展时,由于共祖已不在世,由谁来代表更高级支系?很明显,拥有压倒性权势的支系家长更有机会成为族长。 当若干相邻群体皆发生地位分化之后,权势家庭之间便倾向于相互通婚,并逐渐形成一个上层姻亲网络;这个圈子将带给其成员众多优势:从事甚至垄断跨群体的长距离贸易,在冲突中获得权势姻亲的襄助,影响联盟关系使其有利于自己;经过代代相袭,权势强弱不再只是个人境遇的差别,而成了固有地位,权势者逐渐成为固化成一个贵族阶层。 和族长联盟一样,权势姻亲联盟也可将若干群体连结为一个政治共同体,但效果更好;由于血缘随代际更替而逐渐疏远,单系群不可避免处于持续的分支裂变之中,成吉思汗的儿子们还能紧密合作,孙子辈就开始分裂,但还勉强能召集起忽里勒台,到第四代就形同陌路了;相反,姻亲关系则可以每代刷新,保持亲缘距离不变。 阿兹特克的事例很好的演示了,姻亲联盟在维系一个大型共同体时是如何起作用的;阿兹特克由数百个城邦组成,其中三个强势城邦联合成为霸主,垄断城邦间贸易,并向各邦索取贡赋,国王一般与友邦王室通婚,并通常将其正妻所生嫡女嫁给友邦王族或本邦高级贵族,而将庶女嫁给较低级贵族或有权势的家族首领,类似的,贵族在本邦同侪中通婚,也将庶女嫁给有权势平民,或战功卓著的武士,相比之下,下层平民的婚姻则限于所居住社区,每个社区由若干家族构成内婚群。 这样,在社会结构的每个层次上,国王或贵族通过正妻和嫡子女的婚姻而构建了一个维持该层次统治阶层的横向姻亲联盟,而通过庶妻和庶子女的婚姻则构建了一个纵向姻亲网络,将其合作关系和控制力向下延伸,如此便搭建起一个组织紧密的多层次政治结构,其中每个层次上的姻亲网络有着不同的覆盖范围,因而其合作圈规模皆可限于邓巴数之下。 类似景象在前现代欧洲也可看到,王室在全欧洲联姻,贵族在整个王国通婚,而普通人的婚嫁对象则很少越出邻近几个镇区;得益于阶层分化,婚姻为多层社会同时提供了横向和纵向的粘结纽带,然而,高级政治结构在创造出文明社会之前,许多功能仍有待开发,也还需要其他粘结剂,我会在后面的文章里逐一考察。

【2015-10-29】

@海德沙龙 《欧元危机背后的微观病灶》在有关欧元危机的报道和评论中,货币政策、财政赤字、物价、失业率等宏观因素总是处于议论焦点,微观层面却很少得到关注,经济学家Christian Thimann在比较了各欧元国过去15年贸易差额后发现:顺差国顺差恒增,逆差国逆差同样恒增,这只能从微观方面理解

@whigzhou: 分隔顺差区和逆差区的界线真是太眼熟了~

@whigzhou: 日耳曼vs非日耳曼(more...)

The Coddling of the American Mind

美国精神的娇惯

作者:GREG LUKIANOFF,JONATHAN HAIDT @ 2015-9

译者:Horace Rae(@sheldon_rae)

校对:沈沉(@你在何地-sxy),小册子(@昵称被抢的小册子)

来源:The Atlantic,http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2015/09/the-coddling-of-the-american-mind/399356/

In the name of emotional well-being, college students are increasingly demanding protection from words and ideas they don’t like. Here’s why that’s disastrous for education—and mental health.

以情感安康为名,大学生如今愈发强烈地要求保护自己,不愿听到他们不喜欢的言语和思想。下文解释了为什么这一趋势无论对教育还是心理健康都是灾难性的。

Something strange is happening at America’s colleges and universities. A movement is arising, undirected and driven largely by students, to scrub campuses clean of words, ideas, and subjects that might cause discomfort or give offense. Last December, Jeannie Suk wrote in an online article for The New Yorker about law students asking her fellow professors at Harvard not to teach rape law—or, in one case, even use the word violate (as in “that violates the law”) lest it cause students distress.

当今美国高校中存在一个奇怪的现象。一场运动正在蓬勃发展,它不受引导,主要由学生推动,目的是把可能造成冒犯或引起不适的言语、思想和议题从校园中清除出去。去年12月,Jeannie Suk在《纽约客》一篇在线文章中写到,有法学院的学生要求她在哈佛的同僚停止讲授强奸法——有一次,甚至要求他们停止使用“violate”一词(比如在“that violates the law”中)【译注:该词兼有“违反”、“侵犯”、“亵渎”与“强奸”之义】以免引起学生不适。

In February, Laura Kipnis, a professor at Northwestern University, wrote an essay in The Chronicle of Higher Education describing a new campus politics of sexual paranoia—and was then subjected to a long investigation after students who were offended by the article and by a tweet she’d sent filed Title IX complaints against her.

今年二月,西北大学教授Laura Kipnis在《高等教育纪事报》上发表了一篇文章,讲述高校里新出现的一种性妄想政治,有学生因为被这篇文章以及她发布的一条推特所冒犯,对其提出基于“第九条”的控诉【译注:指《联邦教育法修正案》第九条,禁止教育领域性别歧视】,她因此遭受了漫长的调查。

In June, a professor protecting himself with a pseudonym wrote an essay for Vox describing how gingerly he now has to teach. “I’m a Liberal Professor, and My Liberal Students Terrify Me,” the headline said. A number of popular comedians, including Chris Rock, have stopped performing on college campuses (see Caitlin Flanagan’s article in this month’s issue). Jerry Seinfeld and Bill Maher have publicly condemned the oversensitivity of college students, saying too many of them can’t take a joke.

今年六月,一位使用化名以保护自己的教授为Vox写了一篇文章,描述他现在在教学中需要多么小心翼翼,文章的标题是:“我是一名自由派教授,我被我的自由派学生吓坏了”。包括Chris Rock在内的许多当红谐星,已经不在大学校园演出了(详情见Caitlin Flanagan在本月杂志上的文章)。 Jerry Seinfeld和Bill Maher已公开批评大学生的过度敏感,说他们中太多人连一个玩笑也开不起了。

Two terms have risen quickly from obscurity into common campus parlance.Microaggressions are small actions or word choices that seem on their face to have no malicious intent but that are thought of as a kind of violence nonetheless. For example, by some campus guidelines, it is a microaggression to ask an Asian American or Latino American “Where were you born?,” because this implies that he or she is not a real American.

有两个晦涩的术语已经变成了校园里的日常用语。“微冒犯”(microaggression)表示表面本无恶意但仍被认为具有侵犯性的小举动或用语选择。举个例子,某些校园规则规定,询问亚裔或拉丁裔美国人“你出生在哪里?”就是一种“微冒犯”,因为这一提问暗示了这个人不是真正的美国人。

Trigger warnings are alerts that professors are expected to issue if something in a course might cause a strong emotional response. For example, some students have called for warnings that Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart describes racial violence and that F. Scott Fitzgerald’sThe Great Gatsby portrays misogyny and physical abuse, so that students who have been previously victimized by racism or domestic violence can choose to avoid these works, which they believe might “trigger” a recurrence of past trauma.

“刺激警告”是上课时教授们在讲授易触发强烈情绪波动的内容前被认为应该发出的警告。举个例子,有些学生要求教授预先警告Chinua Achebe的《瓦解》包含有种族暴力内容,F. Scott Fitzgerald的《了不起的盖茨比》描绘了厌女症和肢体暴力。他们认为这些著作可能会“刺激”过往的心灵创伤,因此之前遭受过种族主义和家庭暴力伤害的学生就可以选择跳过这些著作。

Some recent campus actions border on the surreal. In April, at Brandeis University, the Asian American student association sought to raise awareness of microaggressions against Asians through an installation on the steps of an academic hall. The installation gave examples of microaggressions such as “Aren’t you supposed to be good at math?” and “I’m colorblind! I don’t see race.” But a backlash arose among other Asian American students, who felt that the display itself was a microaggression. The association removed the installation, and its president wrote an e-mail to the entire student body apologizing to anyone who was “triggered or hurt by the content of the microaggressions.”

一些近期的校园现象近乎荒诞。今年四月,为了引起对针对亚裔的“微冒犯”的重视,布兰迪斯大学亚裔美国学生联合会在一个学术报告厅的台阶上做了一个展示,内容是“微冒犯”的例子,比如“你们不是应该非常擅长数学吗?”和“我是色盲!我分辨不出种族。”但是另一些亚裔美国学生则提出强烈反对,他们认为这个展示本身就是一种“微冒犯”。后来联合会撤除了这些展品,会长向全体学生发了一封电子邮件,向所有“被‘微冒犯’伤害或刺激”的人道歉。

According to the most-basic tenets of psychology, helping people with anxiety disorders avoid the things they fear is misguided.

按照最基本的心理学原则,帮助焦虑症患者逃避他们所惧怕的事物是完全错误的。

This new climate is slowly being institutionalized, and is affecting what can be said in the classroom, even as a basis for discussion. During the 2014–15 school year, for instance, the deans and department chairs at the 10 University of California system schools were presented by administrators at faculty leader-training sessions with examples of microaggressions. The list of offensive statements included: “America is the land of opportunity” and “I believe the most qualified person should get the job.”

这种新的风气正在渐渐制度化,而且正在影响课堂上可以讲授的内容,甚至成为讨论问题的基础。例如在2014-15学年间,行政官员在教职员领导培训课程上为加州大学系统10所院校的院长和系主任们介绍了“微冒犯”的例子。冒犯性语言的清单包括:“美国是充满机会的国度”和“我相信这份工作应该给最有资格的人”。

The press has typically described these developments as a resurgence of political correctness. That(more...)

This institution will be based on the illimitable freedom of the human mind. For here we are not afraid to follow truth wherever it may lead, nor to tolerate any error so long as reason is left free to combat it. 这一机构的根基在于不受限制的思想自由。因为在这里,我们跟随真理,不惧它把我们带到哪里;也无须忍受任何错误,只要允许理智与之自由对抗。We believe that this is still—and will always be—the best attitude for American universities. Faculty, administrators, students, and the federal government all have a role to play in restoring universities to their historic mission. 我们相信这依旧是——并将一直是——对待美国大学的最佳态度。教师、行政人员,学生,以及联邦政府都有责任让大学回到完成其历史使命的轨道上。 Common Cognitive Distortions 常见的认知扭曲 A partial list from Robert L. Leahy, Stephen J. F. Holland, and Lata K. McGinn’sTreatment Plans and Interventions for Depression and Anxiety Disorders (2012) 这是来自Robert L. Leahy, Stephen J. F. Holland和Lata K. McGinn的《抑郁症和焦虑症的治疗计划及干预措施》(2012年)的一份部分清单。 1.Mind reading.You assume that you know what people think without having sufficient evidence of their thoughts. “He thinks I’m a loser.” 1.读心术。不需要足够的证据,你就认定自己知道别人想的是什么。“他认为我逊毙了。” 2.Fortune-telling.You predict the future negatively: things will get worse, or there is danger ahead. “I’ll fail that exam,” or “I won’t get the job.” 2.悲观预测。你对未来的预测是消极的:事情会越来越糟糕,或者前方危机四伏。“我考试要不及格了”,或者“我得不到这份工作”。 3.Catastrophizing.You believe that what has happened or will happen will be so awful and unbearable that you won’t be able to stand it. “It would be terrible if I failed.” 3.小题大做。你相信将发生或已发生的事情会糟糕得让人难以忍受。“如果我失败了就太糟糕了。” 4.Labeling.You assign global negative traits to yourself and others. “I’m undesirable,” or “He’s a rotten person.” 4.贴标签。你把自己或其他人归类于某些负面特征。“我不受欢迎”或者“他是个堕落的人。” 5.Discounting positives.You claim that the positive things you or others do are trivial. “That’s what wives are supposed to do—so it doesn’t count when she’s nice to me,” or “Those successes were easy, so they don’t matter.” 5.低估正面信息。你声称自己或者其他人做的有意义的事微不足道。“老婆就应该那个样子——所以她对我好不值一提。”或者“这些成功很容易取得,所以算不上什么成就。” 6.Negative filtering.You focus almost exclusively on the negatives and seldom notice the positives. “Look at all of the people who don’t like me.” 6.负面过滤。你几乎只关注负面信息,很少留意正面信息。“看看那些不喜欢我的人吧。” 7.Overgeneralizing.You perceive a global pattern of negatives on the basis of a single incident. “This generally happens to me. I seem to fail at a lot of things.” 7.以偏概全。你通过一件事就认定整体性的负面模式。“这种事总是发生在我身上。好像我有好多事都干不成。” 8.Dichotomous thinking.You view events or people in all-or-nothing terms. “I get rejected by everyone,” or “It was a complete waste of time.” 8.二元思维。你以非此即彼的方式审视人和事。“我被所有人拒绝”或“这完全是浪费时间”。 9.Blaming.You focus on the other person as the source of your negative feelings, and you refuse to take responsibility for changing yourself. “She’s to blame for the way I feel now,” or “My parents caused all my problems.” 9.迁怒于人。你把其他人当作自己负面情绪的来源,不愿意承担改变自己的责任。“我现在感觉这么糟全都是她的错”或“我所有的问题都是我父母造成的”。 10.What if?You keep asking a series of questions about “what if” something happens, and you fail to be satisfied with any of the answers. “Yeah, but what if I get anxious?,” or “What if I can’t catch my breath?” 10.杞人忧天。你一直问“如果某事发生了怎么办?”,并且对所有答案都不满意。“对,但是如果我变得焦虑怎么办?”或者“如果我喘不过气怎么办?” 11.Emotional reasoning.You let your feelings guide your interpretation of reality. “I feel depressed; therefore, my marriage is not working out.” 11.情绪化推理。你让情感引导你去解读现实。“我很沮丧,所以我的婚姻要完蛋了。” 12.Inability to disconfirm.You reject any evidence or arguments that might contradict your negative thoughts. For example, when you have the thought I’m unlovable,you reject as irrelevant any evidence that people like you. Consequently, your thought cannot be refuted. “That’s not the real issue. There are deeper problems. There are other factors.” 12.无法证伪。你拒绝任何和你的消极想法相抵触的证据或观点。举个例子,你认为“没人喜欢我”,你认为证明别人喜欢你的所有证据都毫不相干。所以,你的思想无法被驳斥。“事情不是这样的。肯定有更深层次的问题,还有其他因素。” (编辑:辉格@whigzhou) *注:本译文未经原作者授权,本站对原文不持有也不主张任何权利,如果你恰好对原文拥有权益并希望我们移除相关内容,请私信联系,我们会立即作出响应。

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

The Economic Inequality in Academia

学术界的经济不平等

作者:Richard Goldin @ 2015-8-13

译者:沈沉(@你在何地-sxy)

校对:Who视之

来源:Counterpunch,http://www.counterpunch.org/2015/08/13/progressives-and-the-economic-inequality-in-academia/

In focusing on the wealthy as the singular source of economic inequality, progressive politics obscures the machineries of privilege which function at all levels of society. Individuals are trapped within these mechanisms; their lives lessened in ways that are far more damaging than the actions of the “one per cent.”

进步派政治活动聚焦于有钱人,将之作为经济不平等的唯一源头,从而未能看到在社会各个层面均在发挥作用的特权机制。个体受困于这类机制;他们的生活被削弱,其作用方式远比“1%们”【译注:指占人口总数1%的顶层富人】的行为更为有害。

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

超越邓巴数#3:祖先的记忆

辉格

2015年9月21日

早期人类社会不仅都是小型熟人社会,而且其中成员都是亲缘相当近的亲属,通常由少则六七个多则二十几个扩展大家庭组成;因为规模太小,这样的群体不太可能是将通婚关系限于其内部的内婚群体,而只能实行外婚,实际上往往是从夫居的外婚父系群,即,男性成年后留在出生群体内,女性则嫁出去,加入丈夫所在群体。

之所以父系群更为普遍,同样是因为战争;首先,群体间冲突的一大动机和内容便是诱拐或掳掠对方女性,而诱拐掳掠的结果自然是从夫居。

其次,在两性分工中,战争从来都是男性的专属,因而男性之间的紧密合作对于群体的生存繁荣更为重要,而我们知道,在缺乏其他组织与制度手段的保障时,亲缘关系是促成和强化合作关系的首要因素,而父系群保证了群内男性有着足够近的亲缘。

然而,也正是因为战争所需要的群体内合作倚重于亲缘关系,对紧密合作的要求也就限制了群体规模;因为亲缘关系要转变成合作意愿,需要相应的识别手段,否则,即便一种基于亲缘的合作策略是有利的,也是无法实施的;而随着代际更替,亲缘渐疏,到一定程度之后亲缘关系就变得难以识别了。

对于某位男性来说,群体内其他男性的脸上并未写着“这是我的三重堂兄弟,和我有着1/64的亲缘”,他头脑里也不可能内置了一个基于汉密尔顿不等式(rB>C)的亲选择算法,实际的亲选择策略,只能借助各种现成可用的间接信号,以及对这些信号敏感的情感机制,来引出大致符合策略要求的合作行为。

传统社会常见的父系扩展家庭里,几位已婚兄弟连同妻儿共同生活于同一家户,他们的儿子们(一重堂兄弟)(more...)

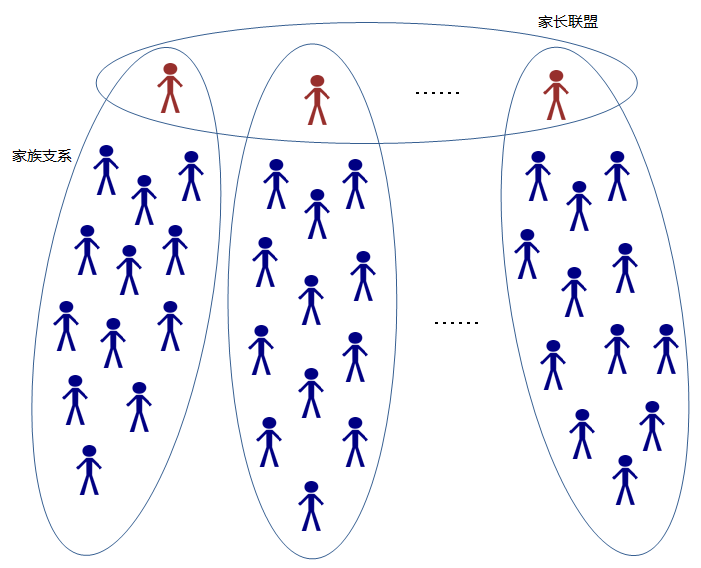

如图所示,若每位家长控制一个十几二十人的扩展家庭,并且二三十位家长(他们是三重以内堂兄弟)组成合作联盟,那么群体规模便可达到三四百,而同时,群内每个成员需要长期交往密切合作的熟人数量仍处于邓巴数之下。这样,当分属两个支系的年轻人发生冲突时,纠纷便可由双方家长出面解决,或提交家长会议裁断,并迫使当事人接受裁决结果。

同样,当群体面临外部威胁,或谋求与其他群体结盟,或准备对外发动攻击等公共事务而需要集体行动时,家长联盟将充当决策与执行机构;也可以这样理解:通过强化父权,家长们把家族树最下面一两层排除出了维持群体团结所需要的那个关键合作圈子,从而避开了邓巴限制。

人类学材料显示,上述模式广泛存在于前国家定居社会,而且它正是在定居之后才出现的;游动性的狩猎采集社会大多是平等主义的,没有高度压制性的父权,长辈也很少向晚辈施加强制性规范,而一旦定居下来(或者游动性减弱),父权便出现了,并且在近代化之前的整个文明史上都占据主导地位;当今世界,凡国家权力所不及的定居社会,像阿富汗、索马里、中东和非洲的部落地区,父权仍非常强大,并且是维持基层社会秩序的主要力量。

父权的常见表现有:对家庭财产的控制,并尽可能的延迟分家,控制子女婚姻,社区内的老人政治;因定居而发展出的财产权,是家长执行父权的强大工具,爱尔兰传统社会的家长,会将财产牢牢控制在手里,即便子女都已成家也不分割家产;一些非洲部族的家长更夸张,当家庭财富增长时,优先用于为自己娶更多妻子,生更多孩子,而不是资助成年子女结婚成家(因而多妻往往与强父权相联系)。

这种做法发展到极致时,老男人们几乎垄断了娶妻机会,在非洲班图语民族(例如西非的约鲁巴人和豪萨人,肯尼亚的康巴人)的许多部落中,父权高度发达,多妻制盛行,男性在熬到40岁前很难娶到妻子,而十岁出头的年轻女孩常常被嫁给五六十岁的老男人;贾瑞德·戴蒙德在检查了大量人类学材料后发现,此类现象广泛存在于传统农牧业定居社会中。

其中原理,我们从进化生物学的亲子冲突(parent-offspring conflict)理论的角度可以看得更清楚:尽管父母和子女很大程度上有着共同利益,但两者利益仍有重大区别,父母希望在各子女间恰当分配家庭资源,以便总体上获得最佳繁衍成效,而每个子女都希望更多资源分给自己这一支,所以不希望父亲生太多孩子。

强大的父权改变了亲子冲突中的力量对比,压制了子女需求中偏离父亲愿望的部分,而且宗族组织的发展又强化了这一父权优势:原本,父代的多子策略高度受限于本人寿命,当预期寿命不够长时,继续生育意义就不大了,因为失去父亲保护的孤儿很可能活不到成年,但有了宗族组织,孤儿就有望被亡父的兄弟、堂兄弟和叔伯收养,甚至得到族内救济制度的帮助(救济制度最初就是伴随宗族组织的发达而出现的)。

将亲子冲突理论稍作扩展,可以让我们更好的理解家长制和部落老人政治:个人在家族树上所居层次(俗称辈份)越高,其个体利益和群体利益的重合度就越高,因而长辈总是比晚辈更多的代表群体利益,他们之间若能达成紧密合作,便有望维持群体和谐,并获得集体行动能力,而同时,因为长辈间亲缘更近,长期熟识的几率也更高,因而紧密合作也更容易达成。

父权和家长联盟为扩大父系群提供了组织手段,不过,若仅限于此,群体规模的扩张将十分有限,因为家长联盟的规模本身受限于邓巴数(还要减去每个支系的规模),若要继续扩张,要么让每位家长控制更多成员,要么让家长联盟发展出多个层级,无论哪种安排,高层联盟中的每位成员都将代表一个比扩展家庭更大的支系。

问题是:谁来代表这个支系?假如寿命足够长,一位曾祖父便可代表四世同堂的大家族(比扩展家庭多出一级),但活的曾祖父太少了;一种解决方案是选举,事实上,部落民主制确实存在于一些古代社会;不过,更自然的安排是让长支拥有优先权(说它“自然”是因为其优先权是自动产生的,无须为此精心安排程序机制),比如周代的宗法制,让长支(大宗)对幼支(小宗)拥有某些支配权,并作为族长代表包含二者的上一级支系。

于是就产生了一个三级宗族结构,理论上,这样的安排可以无限制的迭代,从而产生任意规模的宗族,而同时,每一层级的合作圈都限于几十人规模,因而每位家长或族长需要与之保持长期紧密合作关系的人数,也都限于邓巴数之下。

但实际上,组织能力总是受限于交通、通信和信息处理能力等技术性限制,还有更致命的是,委托代理关系和逐级控制关系的不可靠性,随着层级增加,上层族长越来越无法代表下层支系的利益,也越来越难以对后者施加控制,经验表明,具有某种集体行动能力的多级宗族组织,规模上限大约几千,最多上万。

在古代中国,每当蛮族大规模入侵、中原动荡、王朝崩溃、帝国权力瓦解之际,宗族组织便兴旺起来,聚族自保历来是人们应对乱世的最自然反应,古典时代以来的第一轮宗族运动,便兴起于东晋衣冠南渡之时;如果说第一轮运动主要限于士族大家的话,南宋开始的第二轮运动则吸引了所有阶层的兴趣,家族成员无论贫富贵贱都被编入族谱。

和聚居村落的结构布局一样,宗族组织的紧密程度和集体行动能力同样显著相关于所处环境的安全性,华南农耕拓殖前线,或者国家权力因交通不便而难以覆盖的地方,宗族组织便趋于发达和紧密;人类学家林耀华描述的福建义序黄氏宗族,血缘纽带历二十多代六百多年而不断,到1930年代已发展到15个房支,每房又分若干支系,各有祠堂,从核心家庭到宗族,共达七个组织层级,总人口近万。

类似规模的宗族在华南比比皆是,在宗族之间时而发生的大型械斗中,双方常能组织起上千人的参战队伍,可见其规模之大,行动能力之强;华南许多宗族部分的从福建迁入江西,又从江西迁入湖南,但许多迁出支系与留在原地的支系之间仍能保持定期联系。

共同祖先记忆、父权、家长制、族长会议、大型宗族组织,这些由扩大父系群的种种努力所发展出的文化元素,不仅为定居社会的最初大型化创造了组织基础,也为此后的国家起源提供了部分制度准备,父权和族长权,是早期国家创建者所倚赖的诸多政治权力来源之一。

当然,父系结构的扩展只是社会大型化的多条线索之一,要建立起数十上百万人的大型社会,还有很长的路要走,还要等待其他许多方面的文化进化,在后面的文章里,我会继续追寻人类文明的这段旅程。

(本系列文章首发于“大象公会”,纸媒转载请先征得公会同意。)

如图所示,若每位家长控制一个十几二十人的扩展家庭,并且二三十位家长(他们是三重以内堂兄弟)组成合作联盟,那么群体规模便可达到三四百,而同时,群内每个成员需要长期交往密切合作的熟人数量仍处于邓巴数之下。这样,当分属两个支系的年轻人发生冲突时,纠纷便可由双方家长出面解决,或提交家长会议裁断,并迫使当事人接受裁决结果。

同样,当群体面临外部威胁,或谋求与其他群体结盟,或准备对外发动攻击等公共事务而需要集体行动时,家长联盟将充当决策与执行机构;也可以这样理解:通过强化父权,家长们把家族树最下面一两层排除出了维持群体团结所需要的那个关键合作圈子,从而避开了邓巴限制。

人类学材料显示,上述模式广泛存在于前国家定居社会,而且它正是在定居之后才出现的;游动性的狩猎采集社会大多是平等主义的,没有高度压制性的父权,长辈也很少向晚辈施加强制性规范,而一旦定居下来(或者游动性减弱),父权便出现了,并且在近代化之前的整个文明史上都占据主导地位;当今世界,凡国家权力所不及的定居社会,像阿富汗、索马里、中东和非洲的部落地区,父权仍非常强大,并且是维持基层社会秩序的主要力量。

父权的常见表现有:对家庭财产的控制,并尽可能的延迟分家,控制子女婚姻,社区内的老人政治;因定居而发展出的财产权,是家长执行父权的强大工具,爱尔兰传统社会的家长,会将财产牢牢控制在手里,即便子女都已成家也不分割家产;一些非洲部族的家长更夸张,当家庭财富增长时,优先用于为自己娶更多妻子,生更多孩子,而不是资助成年子女结婚成家(因而多妻往往与强父权相联系)。

这种做法发展到极致时,老男人们几乎垄断了娶妻机会,在非洲班图语民族(例如西非的约鲁巴人和豪萨人,肯尼亚的康巴人)的许多部落中,父权高度发达,多妻制盛行,男性在熬到40岁前很难娶到妻子,而十岁出头的年轻女孩常常被嫁给五六十岁的老男人;贾瑞德·戴蒙德在检查了大量人类学材料后发现,此类现象广泛存在于传统农牧业定居社会中。

其中原理,我们从进化生物学的亲子冲突(parent-offspring conflict)理论的角度可以看得更清楚:尽管父母和子女很大程度上有着共同利益,但两者利益仍有重大区别,父母希望在各子女间恰当分配家庭资源,以便总体上获得最佳繁衍成效,而每个子女都希望更多资源分给自己这一支,所以不希望父亲生太多孩子。

强大的父权改变了亲子冲突中的力量对比,压制了子女需求中偏离父亲愿望的部分,而且宗族组织的发展又强化了这一父权优势:原本,父代的多子策略高度受限于本人寿命,当预期寿命不够长时,继续生育意义就不大了,因为失去父亲保护的孤儿很可能活不到成年,但有了宗族组织,孤儿就有望被亡父的兄弟、堂兄弟和叔伯收养,甚至得到族内救济制度的帮助(救济制度最初就是伴随宗族组织的发达而出现的)。

将亲子冲突理论稍作扩展,可以让我们更好的理解家长制和部落老人政治:个人在家族树上所居层次(俗称辈份)越高,其个体利益和群体利益的重合度就越高,因而长辈总是比晚辈更多的代表群体利益,他们之间若能达成紧密合作,便有望维持群体和谐,并获得集体行动能力,而同时,因为长辈间亲缘更近,长期熟识的几率也更高,因而紧密合作也更容易达成。

父权和家长联盟为扩大父系群提供了组织手段,不过,若仅限于此,群体规模的扩张将十分有限,因为家长联盟的规模本身受限于邓巴数(还要减去每个支系的规模),若要继续扩张,要么让每位家长控制更多成员,要么让家长联盟发展出多个层级,无论哪种安排,高层联盟中的每位成员都将代表一个比扩展家庭更大的支系。

问题是:谁来代表这个支系?假如寿命足够长,一位曾祖父便可代表四世同堂的大家族(比扩展家庭多出一级),但活的曾祖父太少了;一种解决方案是选举,事实上,部落民主制确实存在于一些古代社会;不过,更自然的安排是让长支拥有优先权(说它“自然”是因为其优先权是自动产生的,无须为此精心安排程序机制),比如周代的宗法制,让长支(大宗)对幼支(小宗)拥有某些支配权,并作为族长代表包含二者的上一级支系。

于是就产生了一个三级宗族结构,理论上,这样的安排可以无限制的迭代,从而产生任意规模的宗族,而同时,每一层级的合作圈都限于几十人规模,因而每位家长或族长需要与之保持长期紧密合作关系的人数,也都限于邓巴数之下。

但实际上,组织能力总是受限于交通、通信和信息处理能力等技术性限制,还有更致命的是,委托代理关系和逐级控制关系的不可靠性,随着层级增加,上层族长越来越无法代表下层支系的利益,也越来越难以对后者施加控制,经验表明,具有某种集体行动能力的多级宗族组织,规模上限大约几千,最多上万。

在古代中国,每当蛮族大规模入侵、中原动荡、王朝崩溃、帝国权力瓦解之际,宗族组织便兴旺起来,聚族自保历来是人们应对乱世的最自然反应,古典时代以来的第一轮宗族运动,便兴起于东晋衣冠南渡之时;如果说第一轮运动主要限于士族大家的话,南宋开始的第二轮运动则吸引了所有阶层的兴趣,家族成员无论贫富贵贱都被编入族谱。

和聚居村落的结构布局一样,宗族组织的紧密程度和集体行动能力同样显著相关于所处环境的安全性,华南农耕拓殖前线,或者国家权力因交通不便而难以覆盖的地方,宗族组织便趋于发达和紧密;人类学家林耀华描述的福建义序黄氏宗族,血缘纽带历二十多代六百多年而不断,到1930年代已发展到15个房支,每房又分若干支系,各有祠堂,从核心家庭到宗族,共达七个组织层级,总人口近万。

类似规模的宗族在华南比比皆是,在宗族之间时而发生的大型械斗中,双方常能组织起上千人的参战队伍,可见其规模之大,行动能力之强;华南许多宗族部分的从福建迁入江西,又从江西迁入湖南,但许多迁出支系与留在原地的支系之间仍能保持定期联系。

共同祖先记忆、父权、家长制、族长会议、大型宗族组织,这些由扩大父系群的种种努力所发展出的文化元素,不仅为定居社会的最初大型化创造了组织基础,也为此后的国家起源提供了部分制度准备,父权和族长权,是早期国家创建者所倚赖的诸多政治权力来源之一。

当然,父系结构的扩展只是社会大型化的多条线索之一,要建立起数十上百万人的大型社会,还有很长的路要走,还要等待其他许多方面的文化进化,在后面的文章里,我会继续追寻人类文明的这段旅程。

(本系列文章首发于“大象公会”,纸媒转载请先征得公会同意。)