The Coddling of the American Mind

美国精神的娇惯

作者:GREG LUKIANOFF,JONATHAN HAIDT @ 2015-9

译者:Horace Rae(@sheldon_rae)

校对:沈沉(@你在何地-sxy),小册子(@昵称被抢的小册子)

来源:The Atlantic,

http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2015/09/the-coddling-of-the-american-mind/399356/

In the name of emotional well-being, college students are increasingly demanding protection from words and ideas they don’t like. Here’s why that’s disastrous for education—and mental health.

以情感安康为名,大学生如今愈发强烈地要求保护自己,不愿听到他们不喜欢的言语和思想。下文解释了为什么这一趋势无论对教育还是心理健康都是灾难性的。

Something strange is happening at America’s colleges and universities. A movement is arising, undirected and driven largely by students, to scrub campuses clean of words, ideas, and subjects that might cause discomfort or give offense. Last December, Jeannie Suk wrote in an online article for

The New Yorker about law students asking her fellow professors at Harvard not to teach rape law—or, in one case, even use the word

violate (as in “that violates the law”) lest it cause students distress.

当今美国高校中存在一个奇怪的现象。一场运动正在蓬勃发展,它不受引导,主要由学生推动,目的是把可能造成冒犯或引起不适的言语、思想和议题从校园中清除出去。去年12月,Jeannie Suk在《纽约客》一篇在线文章中写到,有法学院的学生要求她在哈佛的同僚停止讲授强奸法——有一次,甚至要求他们停止使用“violate”一词(比如在“that violates the law”中)【

译注:该词兼有“违反”、“侵犯”、“亵渎”与“强奸”之义】以免引起学生不适。

In February, Laura Kipnis, a professor at Northwestern University, wrote an essay in

The Chronicle of Higher Education describing a new campus politics of sexual paranoia—and was then subjected to a long investigation after students who were offended by the article and by a tweet she’d sent filed Title IX complaints against her.

今年二月,西北大学教授Laura Kipnis在《高等教育纪事报》上发表了一篇文章,讲述高校里新出现的一种性妄想政治,有学生因为被这篇文章以及她发布的一条推特所冒犯,对其提出基于“第九条”的控诉【

译注:指《联邦教育法修正案》第九条,禁止教育领域性别歧视】,她因此遭受了漫长的调查。

In June, a professor protecting himself with a pseudonym wrote an essay for Vox describing how gingerly he now has to teach. “I’m a Liberal Professor, and My Liberal Students Terrify Me,” the headline said. A number of popular comedians, including Chris Rock, have stopped performing on college campuses (see Caitlin Flanagan’s

article in this month’s issue). Jerry Seinfeld and Bill Maher have publicly condemned the oversensitivity of college students, saying too many of them can’t take a joke.

今年六月,一位使用化名以保护自己的教授为Vox写了一篇文章,描述他现在在教学中需要多么小心翼翼,文章的标题是:“我是一名自由派教授,我被我的自由派学生吓坏了”。包括Chris Rock在内的许多当红谐星,已经不在大学校园演出了(详情见Caitlin Flanagan在本月杂志上的文章)。 Jerry Seinfeld和Bill Maher已公开批评大学生的过度敏感,说他们中太多人连一个玩笑也开不起了。

Two terms have risen quickly from obscurity into common campus parlance.

Microaggressions are small actions or word choices that seem on their face to have no malicious intent but that are thought of as a kind of violence nonetheless. For example, by some campus guidelines, it is a microaggression to ask an Asian American or Latino American “Where were you born?,” because this implies that he or she is not a real American.

有两个晦涩的术语已经变成了校园里的日常用语。“微冒犯”(microaggression)表示表面本无恶意但仍被认为具有侵犯性的小举动或用语选择。举个例子,某些校园规则规定,询问亚裔或拉丁裔美国人“你出生在哪里?”就是一种“微冒犯”,因为这一提问暗示了这个人不是真正的美国人。

Trigger warnings are alerts that professors are expected to issue if something in a course might cause a strong emotional response. For example, some students have called for warnings that Chinua Achebe’s

Things Fall Apart describes racial violence and that F. Scott Fitzgerald’s

The Great Gatsby portrays misogyny and physical abuse, so that students who have been previously victimized by racism or domestic violence can choose to avoid these works, which they believe might “trigger” a recurrence of past trauma.

“刺激警告”是上课时教授们在讲授易触发强烈情绪波动的内容前被认为应该发出的警告。举个例子,有些学生要求教授预先警告Chinua Achebe的《瓦解》包含有种族暴力内容,F. Scott Fitzgerald的《了不起的盖茨比》描绘了厌女症和肢体暴力。他们认为这些著作可能会“刺激”过往的心灵创伤,因此之前遭受过种族主义和家庭暴力伤害的学生就可以选择跳过这些著作。

Some recent campus actions border on the surreal. In April, at Brandeis University, the Asian American student association sought to raise awareness of microaggressions against Asians through an installation on the steps of an academic hall. The installation gave examples of microaggressions such as “Aren’t you supposed to be good at math?” and “I’m colorblind! I don’t see race.” But a backlash arose among other Asian American students, who felt that the display itself was a microaggression. The association removed the installation, and its president wrote an e-mail to the entire student body apologizing to anyone who was “triggered or hurt by the content of the microaggressions.”

一些近期的校园现象近乎荒诞。今年四月,为了引起对针对亚裔的“微冒犯”的重视,布兰迪斯大学亚裔美国学生联合会在一个学术报告厅的台阶上做了一个展示,内容是“微冒犯”的例子,比如“你们不是应该非常擅长数学吗?”和“我是色盲!我分辨不出种族。”但是另一些亚裔美国学生则提出强烈反对,他们认为这个展示本身就是一种“微冒犯”。后来联合会撤除了这些展品,会长向全体学生发了一封电子邮件,向所有“被‘微冒犯’伤害或刺激”的人道歉。

According to the most-basic tenets of psychology, helping people with anxiety disorders avoid the things they fear is misguided.

按照最基本的心理学原则,帮助焦虑症患者逃避他们所惧怕的事物是完全错误的。

This new climate is slowly being institutionalized, and is affecting what can be said in the classroom, even as a basis for discussion. During the 2014–15 school year, for instance, the deans and department chairs at the 10 University of California system schools were presented by administrators at faculty leader-training sessions with examples of microaggressions. The list of offensive statements included: “America is the land of opportunity” and “I believe the most qualified person should get the job.”

这种新的风气正在渐渐制度化,而且正在影响课堂上可以讲授的内容,甚至成为讨论问题的基础。例如在2014-15学年间,行政官员在教职员领导培训课程上为加州大学系统10所院校的院长和系主任们介绍了“微冒犯”的例子。冒犯性语言的清单包括:“美国是充满机会的国度”和“我相信这份工作应该给最有资格的人”。

The press has typically described these developments as a resurgence of political correctness. That’s partly right, although there are important differences between what’s happening now and what happened in the 1980s and ’90s. That movement sought to restrict speech (specifically hate speech aimed at marginalized groups), but it also challenged the literary, philosophical, and historical canon, seeking to widen it by including more-diverse perspectives.

媒体通常将这种变化描述为政治正确的复兴。这种说法部分正确,尽管现在发生的事情和上世纪八、九十年代发生的事情存在着重大差异。过去的运动试图限制言论(尤其是针对边缘群体的仇恨言论),但是它们也挑战文学、哲学和历史各方面的正统,试图通过容纳更加多元的视角来对之加以拓展。

The current movement is largely about emotional well-being. More than the last, it presumes an extraordinary fragility of the collegiate psyche, and therefore elevates the goal of protecting students from psychological harm. The ultimate aim, it seems, is to turn campuses into “safe spaces” where young adults are shielded from words and ideas that make some uncomfortable.

当下的运动则主要关注情感安康。不仅如此,它假定大学生的心理脆弱不堪,因此提升了保护学生免受心理伤害这一目标的重要性。这场运动的终极目标,似乎是要屏蔽一切让学生不舒服的言语和观点,把大学校园变成一个“安全场所”。

And more than the last, this movement seeks to punish anyone who interferes with that aim, even accidentally. You might call this impulse

vindictive protectiveness. It is creating a culture in which everyone must think twice before speaking up, lest they face charges of insensitivity, aggression, or worse.

再进一步,这场运动试图让每一个妨碍这一目标的人受到惩罚,无心而为也不可原谅。你可以把这种冲动的念头称作“报复性保护”,它正在创造一种文化,在这种文化下,每一个人都必须三思而后言,以免被人指控麻木不仁、有攻击性,甚至更糟糕的罪名。

We have been studying this development for a while now, with rising alarm. (Greg Lukianoff is a constitutional lawyer and the president and CEO of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, which defends free speech and academic freedom on campus, and has advocated for students and faculty involved in many of the incidents this article describes; Jonathan Haidt is a social psychologist who studies the American culture wars. The stories of how we each came to this subject can be read

here.)

我们研究这场运动已有一段时间了,情况越来越吓人。(Greg Lukianoff是一名宪法律师学者,也是个人教育权利基金会的主席兼CEO。该基金会致力于捍卫校园中的言论自由和学术自由,并且曾声援那些卷入本文所描述诸多事件的学生和教师;Jonathan Haidt是一位社会心理学家,他研究美国的文化战争。关于我们各自都是如何开始研究这个课题的,请见这里

http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2015/09/greg-lukianoffs-story/399359/)

The dangers that these trends pose to scholarship and to the quality of American universities are significant; we could write a whole essay detailing them. But in this essay we focus on a different question: What are the effects of this new protectiveness

on the students themselves? Does it benefit the people it is supposed to help?

这种趋势对学术研究和美国大学教育的质量构成了严重威胁;我们可以写一整篇论文来详细论述。但是本文关注的是另一个问题:这种娇呵严护

对学生自身有什么影响?它是否能帮助到它本打算帮助的人?

What exactly are students learning when they spend four years or more in a community that polices unintentional slights, places warning labels on works of classic literature, and in many other ways conveys the sense that words can be forms of violence that require strict control by campus authorities, who are expected to act as both protectors and prosecutors?

对无意的怠慢加以管制,给经典文学作品贴上警示标签,以其它种种方式传达这么一层意思:言词可能构成暴力,需要受到既被视作保护者又被视作检举人的校方的严格控制——学生花了四年甚至更多时间生活在这样的社区之中,究竟会学到什么呢?

There’s a saying common in education circles: Don’t teach students

what to think; teach them

how to think. The idea goes back at least as far as Socrates. Today, what we call the Socratic method is a way of teaching that fosters critical thinking, in part by encouraging students to question their own unexamined beliefs, as well as the received wisdom of those around them. Such questioning sometimes leads to discomfort, and even to anger, on the way to understanding.

“不要教学生思考

什么,要教给他们

如何思考。”这句话在教育圈内广为人知。这一理念最早起码可追溯至苏格拉底。现在,我们把鼓励批判性思考的教育方法——部分通过鼓励学生质疑自己未经检验的信念以及从周遭等所接收到的知识——称作“苏格拉底法”。在通往理解的道路上,这些质疑可能带来不适,甚至引起愤怒。

But vindictive protectiveness teaches students to think in a very different way. It prepares them poorly for professional life, which often demands intellectual engagement with people and ideas one might find uncongenial or wrong. The harm may be more immediate, too.

但是报复性保护则教育学生以一种完全不同的方式思考。它无法给学生的职业生涯提供多少帮助,因为在职场我们往往需要与我们不认同甚至认为是完全错误的观点和人进行智识交锋。报复性保护也会带来更直接的伤害。

A campus culture devoted to policing speech and punishing speakers is likely to engender patterns of thought that are surprisingly similar to those long identified by cognitive behavioral therapists as causes of depression and anxiety. The new protectiveness may be teaching students to think pathologically.

致力于管制言论和惩罚发声者的校园文化容易导致一种思维方式,它与早已被认知行为治疗师们确认为焦虑症和抑郁症病因的那种思维方式惊人相似。新的保护可能会令学生陷入病态思维。

How Did We Get Here?

何以到了这一步?

It’s difficult to know exactly why vindictive protectiveness has burst forth so powerfully in the past few years. The phenomenon may be related to recent changes in the interpretation of federal antidiscrimination statutes (about which more later). But the answer probably involves generational shifts as well. Childhood itself has changed greatly during the past generation. Many Baby Boomers and Gen Xers can remember riding their bicycles around their hometowns, unchaperoned by adults, by the time they were 8 or 9 years old. In the hours after school, kids were expected to occupy themselves, getting into minor scrapes and learning from their experiences.

想要弄清为什么过去几年报复性保护如此猖獗并不容易。这一现象可能与最近对联邦反歧视法条的解释变化有关(以下稍后再详论这一点),但是答案也可能涉及代际差异,如今的孩童时代和上一代很不一样了。许多“婴儿潮一代”和“X一代”【

译注:约指1965-1975年间生人】还有在家乡骑自行车四处兜风的记忆,当时他们只有八九岁,没有父母陪伴在旁。放学后,孩子们应该自己玩自己的,受些小挫折并从经验中吸取教训。

But “free range” childhood became less common in the 1980s. The surge in crime from the ’60s through the early ’90s made Baby Boomer parents more protective than their own parents had been. Stories of abducted children appeared more frequently in the news, and in 1984, images of them began showing up on milk cartons. In response, many parents pulled in the reins and worked harder to keep their children safe.

但是在1980年代,“放养”的童年越来越少了。1960年代到1990年代初的罪案攀升,使得婴儿潮时期出生的父母们比他们自己的父母更加护犊心切。拐卖儿童的事情越来越常见,在1984年,被拐卖儿童的照片都开始出现在牛奶盒上了。因此,许多家长勒紧了缰绳,努力保证自己孩子的安全。

The flight to safety also happened at school. Dangerous play structures were removed from playgrounds; peanut butter was banned from student lunches. After the 1999 Columbine massacre in Colorado, many schools cracked down on bullying, implementing “zero tolerance” policies. In a variety of ways, children born after 1980—the Millennials—got a consistent message from adults: life is dangerous, but adults will do everything in their power to protect you from harm, not just from strangers but from one another as well.

学校也加强了对安全的重视。操场上的危险游乐设施被拆除;学生午餐中禁用花生黄油。自从1999年科罗拉多州科伦拜恩大屠杀之后,许多学校严厉惩处欺凌事件,实行“零容忍”政策。生于1980年之后的一代——即“千禧一代”——以不同方式从大人们那里得到了一致的信息:生活危机满布,但大人们会竭尽所能保护你们免受伤害,既要防范陌生人,也要防范你们同伴。

These same children grew up in a culture that was (and still is) becoming more politically polarized. Republicans and Democrats have never particularly liked each other, but survey data going back to the 1970s show that on average, their mutual dislike used to be surprisingly mild.

同是这一批孩子,成长在一个政治上日益两极分化的文化中(这一两极化今天仍在继续)。共和党人和民主党人从来都互无好感,但是回溯到1970年代的调查数据显示,两党相互厌恶的程度总体来看也曾出奇地温和。

Negative feelings have grown steadily stronger, however, particularly since the early 2000s. Political scientists call this process “affective partisan polarization,” and it is a very serious problem for any democracy. As each side increasingly demonizes the other, compromise becomes more difficult. A recent study shows that implicit or unconscious biases are now at least as strong across political parties as they are across races.

此后,负面情绪就一直在稳步扩张,在进入新世纪后尤其严重。政治学家称这种现象为“情绪性党派两极化”。这对任何一个民主政体都是很严重的问题。鉴于一方一直在妖魔化另一方,达成共识就越来越困难。近来有研究显示,党派之间隐形和无意识的偏见,丝毫不逊色于种族之间的偏见。

So it’s not hard to imagine why students arriving on campus today might be more desirous of protection and more hostile toward ideological opponents than in generations past. This hostility, and the self-righteousness fueled by strong partisan emotions, can be expected to add force to any moral crusade. A principle of moral psychology is that “morality binds and blinds.” Part of what we do when we make moral judgments is express allegiance to a team. But that can interfere with our ability to think critically. Acknowledging that the other side’s viewpoint has any merit is risky—your teammates may see you as a traitor.

所以,我们不难想象为什么现在的学生比上几代人更加渴望受保护,对意识形态对立方有更强烈的敌意。这种敌意和由强烈党派感情激发的自命正直感,可想而知就是各种道德讨伐的助推器。道德心理学的一条原则是:“道德约束人,也让人盲目。”我们在作出道德判断的时候,同时也表达了对一个群体的忠诚。但是这可能会影响我们进行批判性思考的能力。承认对手的观点具有任何的合理性,风险都很大——队友们可能会把你当成叛徒。

Social media makes it extraordinarily easy to join crusades, express solidarity and outrage, and shun traitors. Facebook was founded in 2004, and since 2006 it has allowed children as young as 13 to join. This means that the first wave of students who spent all their teen years using Facebook reached college in 2011, and graduated from college only this year.

社交媒体使得加入道德讨伐易如反掌,也让表达团结与愤怒和排斥叛徒变得更加容易。Facebook成立于2004年,从2007年开始,它就允许低至13岁的孩子加入。这意味着第一批从青少年时期起就一直在用Facebook的孩子在2011年进入大学,今年才大学毕业。

These first true “social-media natives” may be different from members of previous generations in how they go about sharing their moral judgments and supporting one another in moral campaigns and conflicts. We find much to like about these trends; young people today are engaged with one another, with news stories, and with prosocial endeavors to a greater degree than when the dominant technology was television. But social media has also fundamentally shifted the balance of power in relationships between students and faculty; the latter increasingly fear what students might do to their reputations and careers by stirring up online mobs against them.

第一批真正的“社交媒体原生族”与此前几代人的不同之处,在于他们如何分享道德判断,在道德运动与道德冲突中如何彼此支持。这种趋势有其可喜之处:当今的年轻人与其他人在互相联系,分享新鲜事,与以电视为主导技术的时期相比,对社会交往更为投入。但是社交媒体也从根本上打破了学生和教师之间的权力平衡:后者越来越害怕学生会在网上煽动暴民打击自己,从而损害自己的名声和职业前途。

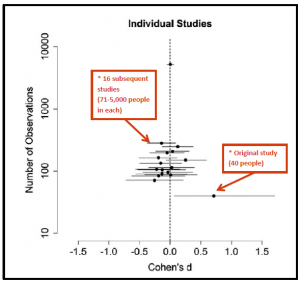

We do not mean to imply simple causation, but rates of mental illness in young adults have been rising, both on campus and off, in recent decades. Some portion of the increase is surely due to better diagnosis and greater willingness to seek help, but most experts seem to agree that some portion of the trend is real.

我们并不打算暗示一种简单的因果关系,但是近几十年来,不管在校内还是校外,青年人患心理疾病的比例都在上升。比例的提高,一定有部分是源于更高的诊断水平和更强的求诊意愿,但是大部分专家似乎都同意,这一统计趋势至少有部分是反映了患病率的真实上升。

Nearly all of the campus mental-health directors surveyed in 2013 by the American College Counseling Association reported that the number of students with severe psychological problems was rising at their schools. The rate of emotional distress reported by students themselves is also high, and rising.

2013年,所有接受美国高校咨询联合会调查的校园心理健康指导员都报告说,自己学校患有严重精神疾病的学生数目在上升。学生自己报告的情绪焦虑比率也很高,而且还在上升。

In a 2014 survey by the American College Health Association, 54 percent of college students surveyed said that they had “felt overwhelming anxiety” in the past 12 months, up from 49 percent in the same survey just five years earlier. Students seem to be reporting more emotional crises; many seem fragile, and this has surely changed the way university faculty and administrators interact with them. The question is whether some of those changes might be doing more harm than good.

2014年,美国高校健康联合会的一个调查显示,54%的大学生表示在过去12个月中“感受到了高度焦虑”,五年前同一调查的结果是49%。学生们报告的情绪危机似乎越来越多;许多人非常脆弱,这当然也改变了高校教师和行政人员与他们互动的方式。问题就是,是否其中有些改变可能弊大于利?

The Thinking Cure

思维治疗

For millennia, philosophers have understood that we don’t see life as it is; we see a version distorted by our hopes, fears, and other attachments. The Buddha said, “Our life is the creation of our mind.” Marcus Aurelius said, “Life itself is but what you deem it.” The quest for wisdom in many traditions begins with this insight. Early Buddhists and the Stoics, for example, developed practices for reducing attachments, thinking more clearly, and finding release from the emotional torments of normal mental life.

几千年来,哲学家们都已经认识到,我们看到的不是生活的本来面目:我们看到的是被我们的期望、恐惧以及其他情感所扭曲的一个版本。佛说:“我们的生活是我们心智的创造物。”马可·奥勒留说:“生活就是我们认为的样子。”在许多文化传统中,对智慧的追求就始于这种观点。例如,早期佛教徒和斯多葛主义者就有通过实践训练去抑制情感,理清思维,以及从日常精神生活的情绪折磨中寻求解脱。

Cognitive behavioral therapy is a modern embodiment of this ancient wisdom. It is the most extensively studied nonpharmaceutical treatment of mental illness, and is used widely to treat depression, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, and addiction. It can even be of help to schizophrenics. No other form of psychotherapy has been shown to work for a broader range of problems.

认知行为治疗是这种古老智慧的现代体现。它是精神疾病非药物疗法中被研究的最多的一种。它被广泛应用于治疗抑郁、焦虑症、进食障碍以及药物成瘾,甚至被用于帮助治疗精神分裂。据我们目前所知,没有其它任何心理治疗方法能治疗更多的疾病。

Studies have generally found that it is as effective as antidepressant drugs (such as Prozac) in the treatment of anxiety and depression. The therapy is relatively quick and easy to learn; after a few months of training, many patients can do it on their own. Unlike drugs, cognitive behavioral therapy keeps working long after treatment is stopped, because it teaches thinking skills that people can continue to use.

研究普遍表明它治疗焦虑和抑郁的功效与抗抑郁药物(比如百忧解)不相上下。这种疗法相对容易学,掌握快,只需几个月的训练,许多患者就可以自行运用了。与药物不同,认知行为疗法在疗程结束后仍长期有效,因为它教给患者的思维方法还能继续使用。

The goal is to minimize distorted thinking and see the world more accurately. You start by learning the names of the dozen or so most common cognitive distortions (such as overgeneralizing, discounting positives, and emotional reasoning; see the list

at the bottom of this article). Each time you notice yourself falling prey to one of them, you name it, describe the facts of the situation, consider alternative interpretations, and then choose an interpretation of events more in line with those facts.

认知行为治疗的目标是尽量令患者减少思想扭曲,从而能更精确地观察世界。开始时,你需要学习最常见的十几种认知扭曲的名目(比如以偏概全、低估正面信息,以及情绪化推理等;完整列表见

文章末尾)。每当你发现自己陷入了其中某种扭曲状况,先对号入座,描述真实状况,思考其他的解释方式,接下来选择与事实较一致的解释。

Your emotions follow your new interpretation. In time, this process becomes automatic. When people improve their mental hygiene in this way—when they free themselves from the repetitive irrational thoughts that had previously filled so much of their consciousness—they become less depressed, anxious, and angry.

新的解释会引导你的情绪。经过一段时间训练之后,这一处理程序会变得很自动。如果以这种方式改善自己的精神健康状况,人们会将自己从原本充斥于意识中的重复性非理性思想中解脱出来,他们的抑郁、焦虑和愤怒都会随之得到缓解。

The parallel to formal education is clear: cognitive behavioral therapy teaches good critical-thinking skills, the sort that educators have striven for so long to impart. By almost any definition, critical thinking requires grounding one’s beliefs in evidence rather than in emotion or desire, and learning how to search for and evaluate evidence that might contradict one’s initial hypothesis. But does campus life today foster critical thinking? Or does it coax students to think in more-distorted ways?

这种疗法与正规教育有着不言而喻的相似之处。认知行为疗法教授良好的批判思维方法,而这正是教育者们长久以来努力要传授的。不论怎么说,批判思维都需要把信念建立在证据而非情感或欲望之上,并且需要人们学习如何寻找可能与自己最初假设相抵触的证据,并加以评判。但是,当今的大学教育鼓励批判思维吗?还是这种教育方式在诱使学生以更扭曲的方式思考?

Let’s look at recent trends in higher education in light of the distortions that cognitive behavioral therapy identifies. We will draw the names and descriptions of these distortions from David D. Burns’s popular book

Feeling Good, as well as from the second edition of

Treatment Plans and Interventions for Depression and Anxiety Disorders, by Robert L. Leahy, Stephen J. F. Holland, and Lata K. McGinn.

让我们按照认知行为疗法界定的各种扭曲来审视近期高等教育中出现的新趋势。我们所使用的思维扭曲的名称和描述,取自David D. Burns广受欢迎的著作《感觉良好》和 Robert L. Leahy, Stephen J. F. Holland和Lata K. McGinn的著作《抑郁症和焦虑症的治疗计划及干预措施》(第二版)。

Higher Education’s Embrace of “Emotional Reasoning”

高等教育欣然接受“情绪化推理”

Burns defines

emotional reasoning as assuming “that your negative emotions necessarily reflect the way things really are: ‘I feel it, therefore it must be true.’ ” Leahy, Holland, and McGinn define it as letting “your feelings guide your interpretation of reality.” But, of course, subjective feelings are not always trustworthy guides; unrestrained, they can cause people to lash out at others who have done nothing wrong. Therapy often involves talking yourself down from the idea that each of your emotional responses represents something true or important.

Burns将“情绪化推理”定义为:预先假定“你的负面情绪一定反映了事实:‘我感觉是这样,所以事情一定是这样’”。 Leahy、Holland和McGinn将其定义为任凭“你的情绪引导你对现实的解释”。但是,主观感受当然并不一定可靠;如果不受抑制,它可能令人们无端指责完全无辜的人。治疗方案通常包括劝自己放弃这种想法:你的每一个情绪反应都代表了重要的或真实的事情。

Emotional reasoning dominates many campus debates and discussions. A claim that someone’s words are “offensive” is not just an expression of one’s own subjective feeling of offendedness. It is, rather, a public charge that the speaker has done something objectively wrong. It is a demand that the speaker apologize or be punished by some authority for committing an offense.

情绪化推理主导了许多校园讨论和辩论。宣称某人的用词“有冒犯性”并不只是表达对于冒犯的主观感受,而是公开指责此人犯了客观错误。这是一种要求,要求说话人道歉,或者要求有关当局惩罚他,因为他犯下了罪行。

There have always been some people who believe they have a right not to be offended. Yet throughout American history—from the Victorian era to the free-speech activism of the 1960s and ’70s—radicals have pushed boundaries and mocked prevailing sensibilities. Sometime in the 1980s, however, college campuses began to focus on preventing offensive speech, especially speech that might be hurtful to women or minority groups. The sentiment underpinning this goal was laudable, but it quickly produced some absurd results.

总有些人相信自己拥有不被冒犯的权利。不过,纵观美国历史——从维多利亚时代到1960和70年代的言论自由运动——激进分子一次次拓展边界,蔑视当时盛行的敏感情绪。然而,在1980年代的某个时候,大学校园开始注重管制冒犯性言论,尤其是可能会对女性或少数族裔造成伤害的言论。这一目标所基于的情操值得赞扬,但是它很快就催生了一些荒诞的后果。

What are we doing to our students if we encourage them to develop extra-thin skin just before they leave the cocoon of adult protection?

如果我们鼓励学生在离开成年人的保护茧之前长出一副超级薄弱的外壳,我们究竟是在做什么?

Among the most famous early examples was the so-called water-buffalo incident at the University of Pennsylvania. In 1993, the university charged an Israeli-born student with racial harassment after he yelled “Shut up, you water buffalo!” to a crowd of black sorority women that was making noise at night outside his dorm-room window.

此类事件最出名的早期案例有发生在宾夕法尼亚大学的所谓“水牛事件”。1993年,该校指控一名生于以色列的学生有种族骚扰罪行,因为他对一些晚上在他宿舍窗外吵闹的黑人女生联谊会成员喊道:“闭嘴,你们这群水牛!”

Many scholars and pundits at the time could not see how the term

water buffalo (a rough translation of a Hebrew insult for a thoughtless or rowdy person) was a racial slur against African Americans, and as a result, the case became international news.

当时,许多学者和专家都不理解“

水牛”这个词是如何构成对非洲裔美国人的种族诽谤的(实际上,水牛是对希伯来语一个辱骂词汇的粗糙翻译,指不顾旁人或吵闹不堪的人),所以,这件事一时成了国际新闻。

Claims of a right not to be offended have continued to arise since then, and universities have continued to privilege them. In a particularly egregious 2008 case, for instance, Indiana University–Purdue University at Indianapolis found a white student guilty of racial harassment for reading a book titled

Notre Dame vs. the Klan. The book honored student opposition to the Ku Klux Klan when it marched on Notre Dame in 1924. Nonetheless, the picture of a Klan rally on the book’s cover offended at least one of the student’s co-workers (he was a janitor as well as a student), and that was enough for a guilty finding by the university’s Affirmative Action Office.

从那时起,对“不被冒犯的权利”的要求开始不断增长,各大学也不断加以纵容。比如,发生在2008年的一个影响极其恶劣的案件中,印第安纳大学与普渡大学印第安纳波利斯联合分校认定一名学生干犯种族骚扰罪行,因为他阅读了一本名叫《圣母大学vs.三K党》的书。这本书纪念了1924年三K党进军圣母大学时反抗他们的学生。虽然如此,该书封面上的三K党集会照片至少冒犯了该学生的一名同事(后者也是学生,同时还是一名楼管)。该大学的反歧视办公室认为这种行为足以构成种族骚扰。

These examples may seem extreme, but the reasoning behind them has become more commonplace on campus in recent years. Last year, at the University of St. Thomas, in Minnesota, an event called Hump Day, which would have allowed people to pet a camel, was abruptly canceled. Students had created a Facebook group where they protested the event for animal cruelty, for being a waste of money, and for being insensitive to people from the Middle East. The inspiration for the camel had almost certainly come from a popular TV commercial in which a camel saunters around an office on a Wednesday, celebrating “hump day”; it was devoid of any reference to Middle Eastern peoples. Nevertheless, the group organizing the event announced on its Facebook page that the event would be canceled because the “program [was] dividing people and would make for an uncomfortable and possibly unsafe environment.”

这些例子也许看起来比较极端,但它们背后的逻辑在大学中近年来越来越常见。去年在明尼苏达州的圣托马斯大学,一个叫驼峰日的活动——意在让人们有机会抚摸一下骆驼——被紧急取消。学生们创建了一个Facebook群组抗议这个活动,理由是虐待动物,浪费金钱,并且不顾及中东学生的感受。该活动的灵感几乎可以肯定是来自一个很受欢迎的电视广告:在某个周三,一只骆驼绕着办公室悠闲散步,庆祝“驼峰日”;它完全和中东人没有关系。尽管如此,活动组织者还是在他们的Facebook主页宣布取消活动,因为“这个活动会造成隔阂,并且可能造成使人不适甚至不安全的环境”。

Because there is a broad ban in academic circles on “blaming the victim,” it is generally considered unacceptable to question the reasonableness (let alone the sincerity) of someone’s emotional state, particularly if those emotions are linked to one’s group identity. The thin argument “I’m offended” becomes an unbeatable trump card. This leads to what Jonathan Rauch, a contributing editor at this magazine, calls the “offendedness sweepstakes,” in which opposing parties use claims of offense as cudgels. In the process, the bar for what we consider unacceptable speech is lowered further and further.

正因为学术圈广泛禁止“批评受害者”,所以质疑一个人的情感状态是否合理基本上不可接受(讨论是否真实就更不用说了),尤其是当情感与群体归属有关的时候。一句单薄的“我被冒犯了”,已成了无往不胜的杀手锏。这就导致了本杂志特约编辑Jonathan Rauch所称的“受辱竞赛”现象:双方都以声称遭到冒犯为武器。在这个过程中,界定“不可接受言论”的门槛越来越低。

Since 2013, new pressure from the federal government has reinforced this trend. Federal antidiscrimination statutes regulate on-campus harassment and unequal treatment based on sex, race, religion, and national origin. Until recently, the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights acknowledged that speech must be “objectively offensive” before it could be deemed actionable as sexual harassment—it would have to pass the “reasonable person” test. To be prohibited, the office wrote in 2003, allegedly harassing speech would have to go “beyond the mere expression of views, words, symbols or thoughts that some person finds offensive.”

从2013年起,来自联邦政府的压力更为这种趋势推波助澜。联邦反歧视法对校园中基于性别、种族、宗教和民族的冒犯和不平等对待进行规制。直到不久前,教育部民权署仍规定只有“客观上具有冒犯性”的言论才能被认定为可提起诉讼的性骚扰——它必须通过“公允人”测试【

译注:是一种程序机制,用于判别一个明事理的、情感和价值取向适度的、且处于中立地位的社会典型成员,在有关情境中将会持何种看法,最常见的公允人测试是陪审团裁决】。2003年,民权署写道,被指为骚扰的言论必须“不仅仅只是令某些人感到冒犯的观点、言语、符号或思想的表达”,才需要禁止。

But in 2013, the Departments of Justice and Education greatly broadened the definition of sexual harassment to include verbal conduct that is simply “unwelcome.” Out of fear of federal investigations, universities are now applying that standard—defining unwelcome speech as harassment—not just to sex, but to race, religion, and veteran status as well. Everyone is supposed to rely upon his or her own subjective feelings to decide whether a comment by a professor or a fellow student is unwelcome, and therefore grounds for a harassment claim. Emotional reasoning is now accepted as evidence.

但是在2013年,司法部和教育部把性骚扰的范围大大扩展,将仅仅“令人反感”的言语也包括了进去。由于害怕联邦政府的调查,现在各大学正将这种标准——把令人反感的言论定性为骚扰——从性领域扩展应用到种族、宗教,以及兵役状况方面。所有人都应该以自己的主观感受为依据来判定教授或同学的评论是否令人反感,并以此作为控告骚扰的依据。情绪化推理现已被当做证据来看待了。

If our universities are teaching students that their emotions can be used effectively as weapons—or at least as evidence in administrative proceedings—then they are teaching students to nurture a kind of hypersensitivity that will lead them into countless drawn-out conflicts in college and beyond. Schools may be training students in thinking styles that will damage their careers and friendships, along with their mental health.

如果我们的大学在教导学生,他们的感情可以作为有力的武器——至少可以作为证据用于行政诉讼之中——那么,大学就是在培养学生的过度敏感,这会导致学生们陷入无休无止的冲突之中,无论是在校期间还是毕业之后。学校教授学生的思维方式,可能会毁掉他们的职业生涯、友谊,以及精神健康。

Fortune-Telling and Trigger Warnings

“悲观预测”与“刺激警告”

Burns defines

fortune-telling as “anticipat[ing] that things will turn out badly” and feeling “convinced that your prediction is an already-established fact.” Leahy, Holland, and McGinn define it as “predict[ing] the future negatively” or seeing potential danger in an everyday situation. The recent spread of demands for trigger warnings on reading assignments with provocative content is an example of fortune-telling.

Burns把“

悲观预测”定义为“预料事情会变糟”而且“确信自己的预测已是既成事实”。Leahy、Holland和McGinn将其定义为“对未来做出负面预测”或者从日常事件中看到潜在风险。近期,对具有刺激性内容的阅读材料发出“刺激警告”的要求正在增加,这正是“悲观预测”的实例。

The idea that words (or smells or any sensory input) can trigger searing memories of past trauma—and intense fear that it may be repeated—has been around at least since World War I, when psychiatrists began treating soldiers for what is now called post-traumatic stress disorder.

文字(或是气味或者任何一种感官输入)会使人回忆起往昔的伤痛,还会引起对这种伤痛再次出现的强烈恐惧,这种观点最早至少可追溯到第一次世界大战时期。当时,精神科医生们开始为士兵们治疗我们现在称之为“创伤后应激障碍”的疾病。

But explicit trigger warnings are believed to have originated much more recently, on message boards in the early days of the Internet. Trigger warnings became particularly prevalent in self-help and feminist forums, where they allowed readers who had suffered from traumatic events like sexual assault to avoid graphic content that might trigger flashbacks or panic attacks.

但人们相信,明确的刺激警告是近期才出现的,最早是在早期互联网的留言板上。刺激警告在自救论坛和女权论坛上广泛流行,这些论坛允许遭受过创伤(比如性侵犯)的读者避开可能引起创伤再现或恐慌发作的图片内容。

Search-engine trends indicate that the phrase broke into mainstream use online around 2011, spiked in 2014, and reached an all-time high in 2015. The use of trigger warnings on campus appears to have followed a similar trajectory; seemingly overnight, students at universities across the country have begun demanding that their professors issue warnings before covering material that might evoke a negative emotional response.

搜索引擎的热词统计显示,在网络上这一术语于2011年进入主流用语,2014年使用量激增,2015年的搜索量达到历史最高。“刺激警告”一词在校园里的使用情况也遵循着同一发展轨迹,仿佛一夜之间,全国的大学生们都开始要求教授在讲授可能引起负面情绪反应的内容前发出警告。

In 2013, a task force composed of administrators, students, recent alumni, and one faculty member at Oberlin College, in Ohio, released an online resource guide for faculty (subsequently retracted in the face of faculty pushback) that included a list of topics warranting trigger warnings. These topics included classism and privilege, among many others. The task force recommended that materials that might trigger negative reactions among students be avoided altogether unless they “contribute directly” to course goals, and suggested that works that were “too important to avoid” be made optional.

2013年,俄亥俄州奥柏林学院一个由行政人员、学生、近期毕业的校友和一名教员组成的特别工作组在网上发表了一份在线资料指南(之后因教职员工反对而撤回),罗列了应当提出“刺激警告”的题材,包括阶级歧视论和特权论,及许多其他内容。这个工作组建议全面剔除可能引起学生负面反应的内容,除非这些内容对课程目标“有直接作用”。工作组还建议将“不可不读”的书目调整成选读内容。

It’s hard to imagine how novels illustrating classism and privilege could provoke or reactivate the kind of terror that is typically implicated in PTSD. Rather, trigger warnings are sometimes demanded for a long list of ideas and attitudes that some students find politically offensive, in the name of preventing other students from being harmed. This is an example of what psychologists call “motivated reasoning”—we spontaneously generate arguments for conclusions we want to support.

那些“创伤后应激障碍”通常所牵涉的恐慌,很难想象会被描绘阶级歧视论和特权论的小说唤起或重新激发出来。确切地说,只有在某些学生眼中有政治冒犯色彩的一系列观念和言论才需要刺激警告,名为避免其他同学受伤害。这就是心理学家所称的“动机性推理”的实例:我们不由自主地为我们想要支持的结论制造论据。

Once

you find something hateful, it is easy to argue that exposure to the hateful thing could traumatize some

other people. You believe that you know how others will react, and that their reaction could be devastating. Preventing that devastation becomes a moral obligation for the whole community. Books for which students have called publicly for trigger warnings within the past couple of years include Virginia Woolf’s

Mrs. Dalloway (at Rutgers, for “suicidal inclinations”) and Ovid’s

Metamorphoses (at Columbia, for sexual assault).

如果

你觉得某些东西令你憎恨,就很容易认为

其他人与它们接触会受到创伤。你认为你知道别人会作何反应:他们可能会崩溃。避免这种情感崩溃成了整个社会的道德责任。最近几年,学生们公开要求提供刺激警告的著作包括弗吉尼亚·伍尔夫的《达洛维夫人》(在罗格斯大学,因“自杀倾向”)和奥维德的《变形记》(在哥伦比亚大学,因“性侵犯”)。

Jeannie Suk’s

New Yorker essay described the difficulties of teaching rape law in the age of trigger warnings. Some students, she wrote, have pressured their professors to avoid teaching the subject in order to protect themselves and their classmates from potential distress. Suk compares this to trying to teach “a medical student who is training to be a surgeon but who fears that he’ll become distressed if he sees or handles blood.”

Jeannie Suk在《纽约客》发表的文章讲述了在刺激警告盛行的时代讲授强奸法有多么困难。她写道,有些学生向教授施压,不许教授讲授这一课程,以免自己和同学们可能会承受精神痛苦。Suk将这种境况比作试图教“将要成为外科医生但害怕自己晕血的医学生”。

However, there is a deeper problem with trigger warnings. According to the most-basic tenets of psychology, the very idea of helping people with anxiety disorders avoid the things they fear is misguided. A person who is trapped in an elevator during a power outage may panic and think she is going to die. That frightening experience can change neural connections in her amygdala, leading to an elevator phobia. If you want this woman to retain her fear for life, you should help her avoid elevators.

然而,刺激警告还会带来更深层的问题,根据最基本的心理学原则,帮助焦虑症患者逃避他们所惧怕的事物是完全错误的。停电时被困在电梯里的人可能会慌了手脚,以为自己快要死了。这种可怕的经历会改变这个人大脑杏仁核中神经元的反应,导致电梯恐惧症。如果你想让这个女人在余生中保持恐惧,你就应该帮助她远离电梯。

But if you want to help her return to normalcy, you should take your cues from Ivan Pavlov and guide her through a process known as exposure therapy. You might start by asking the woman to merely look at an elevator from a distance—standing in a building lobby, perhaps—until her apprehension begins to subside. If nothing bad happens while she’s standing in the lobby—if the fear is not “reinforced”—then she will begin to learn a new association: elevators are not dangerous. (This reduction in fear during exposure is called habituation.) Then, on subsequent days, you might ask her to get closer, and on later days to push the call button, and eventually to step in and go up one floor. This is how the amygdala can get rewired again to associate a previously feared situation with safety or normalcy.

但是,如果你想让她回归正常,你就应该采用巴甫洛夫的方法,为她进行“暴露治疗”。开始时,你可以让这个女人远观电梯——比如站在大堂里——直到她的不安平复下来。如果站在大堂没有大碍,她的恐惧没有“加强”,她就会开始建立一个新的认识:电梯并不危险。(这种在接触过程中的恐惧消退叫做“习惯化”)。接下来几天,你可以要求她靠近电梯,再之后几天按下电梯按钮,最后走进电梯,上一层楼。这样,杏仁核就会将之前害怕的境况重新与安全和正常联系起来。

Students who call for trigger warnings may be correct that some of their peers are harboring memories of trauma that could be reactivated by course readings. But they are wrong to try to prevent such reactivations. Students with PTSD should of course get treatment, but they should not try to avoid normal life, with its many opportunities for habituation.

要求刺激警告的学生在这一点上可能是正确的:他们的某些同学可能还有创伤记忆,这些记忆可能被阅读材料重新唤起。但是他们要避免唤起这些记忆,却是错误的。患有创伤后应激障碍的学生理应得到治疗,但他们不应该试图回避正常生活,这样他们就错失了许多适应的机会。

Classroom discussions are safe places to be exposed to incidental reminders of trauma (such as the word

violate). A discussion of violence is unlikely to be followed by actual violence, so it is a good way to help students change the associations that are causing them discomfort. And they’d better get their habituation done in college, because the world beyond college will be far less willing to accommodate requests for trigger warnings and opt-outs.

课堂讨论是偶然接触易于引发创伤回忆的事物(比如词语“强奸”)的安全环境。针对暴力的讨论不大可能伴随真实的暴力,所以这种讨论是帮助学生改变引发不适联想的一剂良方。并且,学生们最好在大学中完成适应过程,因为校园外的世界可不那么愿意满足学生对刺激警告的要求,或者让他们选择半路退出。

The expansive use of trigger warnings may also foster unhealthy mental habits in the vastly larger group of students who do not suffer from PTSD or other anxiety disorders. People acquire their fears not just from their own past experiences, but from social learning as well. If everyone around you acts as though something is dangerous—elevators, certain neighborhoods, novels depicting racism—then you are at risk of acquiring that fear too.

对于更多没有患创伤后应激障碍或其他焦虑症的学生来说,刺激警告的大范围应用也会滋长他们不健康的心理习惯。人们的恐惧,不仅仅来自于自己的经验,也来自于从社会学习。如果你身边的所有人都表现得像是害怕某种东西——电梯、某一片区域、描述种族主义的小说——你也有可能对此产生恐惧。

The psychiatrist Sarah Roff pointed this out last year in an online article for

The Chronicle of Higher Education. “One of my biggest concerns about trigger warnings,” Roff wrote, “is that they will apply not just to those who have experienced trauma, but to all students, creating an atmosphere in which they are encouraged to believe that there is something dangerous or damaging about discussing difficult aspects of our history.”

精神医生Sarah Roff在《高等教育纪事报》的一篇在线文章中指出了这一点。Roff写道:“我对刺激警告最大的担忧在于,它不仅会影响受过创伤的学生,它还会影响所有学生。它创造了一种氛围,令学生相信讨论历史的阴暗面很危险,会造成伤害。”

The new climate is slowly being institutionalized, and is affecting what can be said in the classroom, even as a basis for discussion or debate.

这种新的风气正在渐渐制度化,而且正在影响课堂上可以讨论的内容,甚至成为讨论的基础。

In an article published last year by

Inside Higher Ed, seven humanities professors wrote that the trigger-warning movement was “already having a chilling effect on [their] teaching and pedagogy.” They reported their colleagues’ receiving “phone calls from deans and other administrators investigating student complaints that they have included ‘triggering’ material in their courses, with or without warnings.”

去年,在《高等教育内部观察》的一篇文章中,七位人文学科教授写道,刺激警告运动“已经严重影响(他们的)教学。”他们说,他们的同事“接到院长和其他行政人员的电话,调查学生对他们的投诉:他们在有警告或无警告的情况下,在课程中包含了‘刺激性’内容。”

A trigger warning, they wrote, “serves as a guarantee that students will not experience unexpected discomfort and implies that if they do, a contract has been broken.” When students come to

expect trigger warnings for any material that makes them uncomfortable, the easiest way for faculty to stay out of trouble is to avoid material that might upset the most sensitive student in the class.

他们写道,一个刺激警告“保证学生不会遭受意外的不适,并且暗示如果这种情况出现了,教师们就违反了契约。”如果学生们要求在所有引起不适的材料前提供刺激警告,教师们避免麻烦的最佳方式,就是剔除有可能会冒犯班级中最敏感学生的材料。

Magnification, Labeling, and Microaggressions

夸大、贴标签和微冒犯

Burns defines

magnification as “exaggerat[ing] the importance of things,” and Leahy, Holland, and McGinn define

labeling as “assign[ing] global negative traits to yourself and others.” The recent collegiate trend of uncovering allegedly racist, sexist, classist, or otherwise discriminatory microaggressions doesn’t

incidentally teach students to focus on small or accidental slights. Its

purpose is to get students to focus on them and then relabel the people who have made such remarks as aggressors.

Burns把“夸大”定义为“夸张描述事物的重要性”,Leahy、 Holland和McGinn把“贴标签”定义为“把自己或其他人归类于某些负面特征。”近期,大学中有越来越多的个案揭发所谓种族主义、性别歧视、阶级歧视,或者其他歧视性的微冒犯。这种趋势并不是就着事件引导学生们去关注细微或无意识的怠慢。它的

目的就是让学生们关注这些东西,然后给说这些话的人贴上侵犯者的标签。

The term

microaggression originated in the 1970s and referred to subtle, often unconscious racist affronts. The definition has expanded in recent years to include anything that can be perceived as discriminatory on virtually any basis. For example, in 2013, a student group at UCLA staged a sit-in during a class taught by Val Rust, an education professor. The group read a letter aloud expressing their concerns about the campus’s hostility toward students of color. Although Rust was not explicitly named, the group quite clearly criticized his teaching as microaggressive. In the course of correcting his students’ grammar and spelling, Rust had noted that a student had wrongly capitalized the first letter of the word

indigenous. Lowercasing the capital

I was an insult to the student and her ideology, the group claimed.

“微冒犯”一词产生于1970年代,意指微妙的、通常属于无意识的种族冒犯。近些年,其定义已经扩展到包含几乎任何语境下所有被认为具有歧视性的言论和行为。举个例子,2013年加州大学洛杉矶分校的一个学生团体旁听了教育学教授Val Rust讲授的一节课。这个团体大声宣读了一封信,表示对校园里针对有色人种学生的敌意深感忧虑。尽管没有直接点Rust的名,这个团体显然是在批评他的教学有“微冒犯性”。在纠正学生的语法和拼写的过程中,Rust注意到一个学生错误地把“indigenous”(土著的)的首字母大写了。这个团体宣称,把首字母“i”小写侮辱了这名学生和她的意识形态。

Even joking about microaggressions can be seen as an aggression, warranting punishment. Last fall, Omar Mahmood, a student at the University of Michigan, wrote a satirical column for a conservative student publication,

The Michigan Review, poking fun at what he saw as a campus tendency to perceive microaggressions in just about anything. Mahmood was also employed at the campus newspaper,

The Michigan Daily.

The Daily’s editors said that the way Mahmood had “satirically mocked the experiences of fellow Daily contributors and minority communities on campus … created a conflict of interest.”

就算是拿微冒犯开玩笑也会被视为冒犯,并带来惩罚。去年夏天,密歇根大学的学生Omar Mahmood为一份保守派学生刊物《密歇根评论》写了一篇讽刺性的专栏文章,讽刺他看到的当下大学中把一切都视作微冒犯的趋势。Omar Mahmood也供职于校报《密歇根日报》。《密歇根日报》的编辑说Mahmood“讽刺本杂志撰稿人和校园中少数族裔的经历”的方式“制造了利益冲突”。

The Daily terminated Mahmood after he described the incident to two Web sites, The College Fix and The Daily Caller. A group of women later vandalized Mahmood’s doorway with eggs, hot dogs, gum, and notes with messages such as “Everyone hates you, you violent prick.” When speech comes to be seen as a form of violence, vindictive protectiveness can justify a hostile, and perhaps even violent, response.

在Mahmood向两家网站——The College Fix和The Daily Caller——讲述了这一事件之后,《密歇根日报》解雇了他。后来,一帮女人在Mahmood家门口用鸡蛋、热狗、口香糖和写有诸如“所有的人都恨你,你这个暴徒”之类文字的便条大搞破坏。当言论被视作一种暴力时,报复性保护就为恶意报复,甚至暴力行为赋予了正当性。

In March, the student government at Ithaca College, in upstate New York, went so far as to propose the creation of an anonymous microaggression-reporting system. Student sponsors envisioned some form of disciplinary action against “oppressors” engaged in belittling speech. One of the sponsors of the program said that while “not … every instance will require trial or some kind of harsh punishment,” she wanted the program to be “record-keeping but with impact.”

今年三月,纽约州北部地区的伊萨卡学院,学生会甚至提议建立匿名的微冒犯举报机制。提议的学生设想出一套针对发表歧视性言论的“压迫者”的纪律性惩罚。该项目的一位提议者说,虽然“并不是每一个案例都需要审讯或者某种严酷惩罚”,但是她希望这个项目能“留下记录,产生影响”。

Surely people make subtle or thinly veiled racist or sexist remarks on college campuses, and it is right for students to raise questions and initiate discussions about such cases. But the increased focus on microaggressions coupled with the endorsement of emotional reasoning is a formula for a constant state of outrage, even toward well-meaning speakers trying to engage in genuine discussion.

当然了,人们的确会在大学校园发表委婉的或是稍稍遮掩的种族歧视和性别歧视言论,学生们质疑这种状况并发起讨论也是正确的。但是对微冒犯的关注持续增长加上对情绪化推理的支持,结果就是持续性的愤怒,这种愤怒甚至会针对真心想要讨论问题的善意说话者。

What are we doing to our students if we encourage them to develop extra-thin skin in the years just before they leave the cocoon of adult protection and enter the workforce? Would they not be better prepared to flourish if we taught them to question their own emotional reactions, and to give people the benefit of the doubt?

如果我们鼓励学生在离开成年人的保护茧、踏入工作岗位之前长出一副超级薄弱的外壳,我们究竟是在做什么?如果我们教会他们质疑自己的情绪化反应、不要妄下定论,他们难道不是会表现得更好吗?

Teaching Students to Catastrophize and Have Zero Tolerance

教导学生小题大做、零容忍。

Burns defines

catastrophizing as a kind of magnification that turns “commonplace negative events into nightmarish monsters.” Leahy, Holland, and McGinn define it as believing “that what has happened or will happen” is “so awful and unbearable that you won’t be able to stand it.” Requests for trigger warnings involve catastrophizing, but this way of thinking colors other areas of campus thought as well.

Burns把“小题大做”定义为“把寻常的负面事物当做梦魇般的妖魔鬼怪”的夸大行为。Leahy、Holland和McGinn把它定义为相信“已发生或将发生之事糟糕得让人难以忍受,乃至你经受不住”。对刺激警告的需求中包含着小题大做的成分,但是这种思考方式也干扰了大学中的其他思想。

Catastrophizing rhetoric about physical danger is employed by campus administrators more commonly than you might think—sometimes, it seems, with cynical ends in mind. For instance, last year administrators at Bergen Community College, in New Jersey, suspended Francis Schmidt, a professor, after he posted a picture of his daughter on his Google+ account. The photo showed her in a yoga pose, wearing a T-shirt that read I will take what is mine with fire & blood, a quote from the HBO show

Game of Thrones.

在大学管理者中,描述人身伤害时“小题大做”的情况要比你想象得普遍——有时候看起来像是抱着愤世嫉俗的目的一样。举个例子,新泽西州卑尔根社区学院的教授Francis Schmidt去年在他的Google+账号上发布了一张他女儿的照片之后,被该学院的管理者停职了。照片中,他女儿正做着瑜伽动作,T恤衫上写着“我要用血与火来赢回属于我的一切”,这句话引自HBO的电视剧《权利的游戏》。

Schmidt had filed a grievance against the school about two months earlier after being passed over for a sabbatical. The quote was interpreted as a threat by a campus administrator, who received a notification after Schmidt posted the picture; it had been sent, automatically, to a whole group of contacts. According to Schmidt, a Bergen security official present at a subsequent meeting between administrators and Schmidt thought the word

fire could refer to AK-47s.

两个月之前,因为停教休假的请求被拒绝,Schmidt曾向学校表达过不满。在Schmid发布那张照片之后,照片被自动发送给了一组联系人。一位大学管理者得到了推送消息,然后把那张照片解读成了威胁信息。据Schmidt所说,在随后管理者与Schmidt会面时,一位出席的安全官员认为“火”也可能是暗指AK-47。

Then there is the eight-year legal saga at Valdosta State University, in Georgia, where a student was expelled for protesting the construction of a parking garage by posting an allegedly “threatening” collage on Facebook. The collage described the proposed structure as a “memorial” parking garage—a joke referring to a claim by the university president that the garage would be part of his legacy. The president interpreted the collage as a threat against his life.

然后还有佐治亚州瓦尔多斯塔州立大学长达八年的传奇官司。该大学开除了一名学生,因为他为了抗议一个室内停车场的修建,在Facebbok上发表了一幅据称有“威胁性”的拼贴画。那幅画把这个规划中的设施称为“纪念性”停车场。这是个玩笑,影射的是大学校长曾经说过的:这座停车场将会成为他为学校留下的遗产。这位校长将该拼贴画理解为死亡恐吓。

It should be no surprise that students are exhibiting similar sensitivity. At the University of Central Florida in 2013, for example, Hyung-il Jung, an accounting instructor, was suspended after a student reported that Jung had made a threatening comment during a review session. Jung explained to the

Orlando Sentinel that the material he was reviewing was difficult, and he’d noticed the pained look on students’ faces, so he made a joke. “It looks like you guys are being slowly suffocated by these questions,” he recalled saying. “Am I on a killing spree or what?”

学生们表现出类似的敏感也就不足为奇了。举个例子,中佛罗里达大学的会计学讲师Hyung-il Jung在2013年被学校停职,因为学生举报他在一节复习课中表达了威胁性言论。Jung向《奥兰多哨兵报》解释说,他在辅导的材料很难,他还注意到了学生们脸上痛苦的表情,所以他开了一个玩笑。他回忆他当时曾说:“你们好像快要被这些问题憋死在这里了呢”,“我这不是在玩杀人游戏吗?”

After the student reported Jung’s comment, a group of nearly 20 others e-mailed the UCF administration explaining that the comment had clearly been made in jest. Nevertheless, UCF suspended Jung from all university duties and demanded that he obtain written certification from a mental-health professional that he was “not a threat to [himself] or to the university community” before he would be allowed to return to campus.

在学生举报了Jung的言论之后,有差不多二十个人给中佛罗里达大学的管理部门发电子邮件,解释说那些明显只是玩笑话。尽管如此,中佛罗里达大学还是暂停了Jung的一切学校职务,并且要求他要在获得了来自精神健康专家的书面认可,证明他“对自己和学校成员都不构成威胁”之后,才能回学校上班。

All of these actions teach a common lesson: smart people do, in fact, overreact to innocuous speech, make mountains out of molehills, and seek punishment for anyone whose words make anyone else feel uncomfortable.

这些事情给了我们同一个教训:聪明人真的会对无伤大雅的言辞反应过度,小题大做,然后要求惩罚所有说过让任何一个人不舒服的话的人。

Mental Filtering and Disinvitation Season

“思维过滤”和“撤邀时节”

As Burns defines it,

mental filtering is “pick[ing] out a negative detail in any situation and dwell[ing] on it exclusively, thus perceiving that the whole situation is negative.” Leahy, Holland, and McGinn refer to this as “negative filtering,” which they define as “focus[ing] almost exclusively on the negatives and seldom notic[ing] the positives.” When applied to campus life, mental filtering allows for simpleminded demonization.

按照Burns的定义,“思维过滤”是“从事件中筛选出负面细节,然后只抓住负面细节不放,因而认为整件事都是负面的。”Leahy、Holland和McGinn把它命名为“负面信息过滤”,他们把它定义为“只关注负面,很少留意正面。”把这一概念应用到大学校园,思维过滤使得不加考虑地妖魔化他人成为可能。

Students and faculty members in large numbers modeled this cognitive distortion during 2014’s “disinvitation season.” That’s the time of year—usually early spring—when commencement speakers are announced and when students and professors demand that some of those speakers be disinvited because of things they have said or done. According to data compiled by the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, since 2000, at least 240 campaigns have been launched at U.S. universities to prevent public figures from appearing at campus events; most of them have occurred since 2009.

2014年的“撤邀时节”中,大量学生和教职员示范了这种认知扭曲。那是每年宣布毕业典礼演讲人的时间——通常是早春,由于某些演讲者做过的事和说过的话,学生们和教授们要求撤回对他们的邀请。根据个人教育权利基金会整理的数据,自2000年起,美国大学中至少发起了240场抵制公众人物出席大学活动的运动,其中大部分都发生在2009年以后。

Consider two of the most prominent disinvitation targets of 2014: former U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice and the International Monetary Fund’s managing director, Christine Lagarde. Rice was the first black female secretary of state; Lagarde was the first woman to become finance minister of a G8 country and the first female head of the IMF. Both speakers could have been seen as highly successful role models for female students, and Rice for minority students as well. But the critics, in effect, discounted any possibility of something positive coming from those speeches.

让我们仔细想想2014年被要求撤回邀请的最知名的两个人:前国务卿康多莉扎·赖斯和国际货币基金组织(IMF)总裁克里斯蒂娜·拉加德。赖斯是首位黑人女国务卿;拉加德是G8国家首位女财长,也是IMF首位女掌门人。这两个人都应该被视作女性学生的杰出榜样才是,赖斯还是少数族裔的榜样。但是,批评者们实际上认为这两人的演讲不可能有什么积极意义。

Members of an academic community should of course be free to raise questions about Rice’s role in the Iraq War or to look skeptically at the IMF’s policies. But should dislike of

part of a person’s record disqualify her altogether from sharing her perspectives?

学者们自然可以自由地质疑赖斯在伊拉克战争中的角色,或者用怀疑的眼光审视IMF的政策,但是一个人的

某一部分经历令人生厌就意味着这个人没有资格分享她的见解吗?

If campus culture conveys the idea that visitors must be pure, with résumés that never offend generally left-leaning campus sensibilities, then higher education will have taken a further step toward intellectual homogeneity and the creation of an environment in which students rarely encounter diverse viewpoints. And universities will have reinforced the belief that it’s okay to filter out the positive. If students graduate believing that they can learn nothing from people they dislike or from those with whom they disagree, we will have done them a great intellectual disservice.

如果大学文化传递的信息是“来访者必须纯洁无暇,其简历完全不曾伤害总体左倾的校园感情”,那么,高等教育就向智力同质化又迈进一步,并且为学生创造了一个遇不到多元化观点的环境。大学也将对“过滤掉积极方面是可以的”这一信念加以巩固。如果学生们毕业的时候相信他们从自己讨厌或反对的人那里学不到任何东西,我们就对他们的智力造成了很大伤害。

What Can We Do Now?

我们现在能做些什么?

Attempts to shield students from words, ideas, and people that might cause them emotional discomfort are bad for the students. They are bad for the workplace, which will be mired in unending litigation if student expectations of safety are carried forward. And they are bad for American democracy, which is already paralyzed by worsening partisanship. When the ideas, values, and speech of the other side are seen not just as wrong but as willfully aggressive toward innocent victims, it is hard to imagine the kind of mutual respect, negotiation, and compromise that are needed to make politics a positive-sum game.

这种试图把学生和可能令他们感情上不舒服的言语、思想和人物隔离开来的做法,贻害无穷。这种努力对职场无益,如果学生还对安全抱着同样的期望,他们在工作场所会陷入没完没了的官司。这对美国的民主也是有害的,这种民主本来就已经被日益恶化的党派纷争破坏得千疮百孔了。当对手的思想、价值观和言论不仅仅被看做是错误观点,而且被看做是对无辜受害人的蓄意伤害,很难想象我们还能找到令政治成为正和博弈的那种相互尊重、友好协商和相互妥协。

Rather than trying to protect students from words and ideas that they will inevitably encounter, colleges should do all they can to equip students to thrive in a world full of words and ideas that they cannot control. One of the great truths taught by Buddhism (and Stoicism, Hinduism, and many other traditions) is that you can never achieve happiness by making the world conform to your desires. But you can master your desires and habits of thought. This, of course, is the goal of cognitive behavioral therapy. With this in mind, here are some steps that might help reverse the tide of bad thinking on campus.

与其帮助学生避免接触他们必然遇到的言词和观点,大学更应该尽力武装学生,让他们在这个言论不受他们控制的世界里茁壮成长。佛教(以及斯多葛学派、印度教和许多其他传统思想)教给我们的真理之一就是,通过让世界顺应你的要求来获得快乐是永远不可能的。但是你可以掌控自己的思维习惯和欲望。当然了,这就是认知行为疗法的目标。意识到这一点以后,以下是一些可能帮助大学逆转不良思维的步骤。

The biggest single step in the right direction does not involve faculty or university administrators, but rather the federal government, which should release universities from their fear of unreasonable investigation and sanctions by the Department of Education. Congress should define peer-on-peer harassment according to the Supreme Court’s definition in the 1999 case

Davis v. Monroe County Board of Education. The

Davis standard holds that a single comment or thoughtless remark by a student does not equal harassment; harassment requires a pattern of objectively offensive behavior by one student that interferes with another student’s access to education. Establishing the

Davis standard would help eliminate universities’ impulse to police their students’ speech so carefully.

迈向正路最重要的一步,需要的不是教职员或者学校管理者,而是联邦政府。政府应该让大学免受教育部不合理的调查和处罚。国会应该按照1999年最高法院在Davis诉门罗郡教育委员会一案中的定义来确定“朋辈间骚扰”的定义。“Davis标准”认定学生所作的一句个别评论或者一句无心话语并不构成骚扰;只有干扰他人正常受教育而且蓄意冒犯别人的惯常行为方式才能构成骚扰。贯彻“Davis标准”,可以避免激发大学严厉管制学生言论。

Universities themselves should try to raise consciousness about the need to balance freedom of speech with the need to make all students feel welcome. Talking openly about such conflicting but important values is just the sort of challenging exercise that any diverse but tolerant community must learn to do. Restrictive speech codes should be abandoned.

大学本身应该深化认识,提醒大家在保证言论自由和保证每个学生都舒服之间需要取得平衡。公开谈论这种具有冲突性却又至关重要的价值,是每个多元而宽容的社会必须学会的挑战。限制性的言论准则应该被废除。

Universities should also officially and strongly discourage trigger warnings. They should endorse the American Association of University Professors’ report on these warnings, which notes, “The presumption that students need to be protected rather than challenged in a classroom is at once infantilizing and anti-intellectual.”

大学也必须从官方立场正式且严厉的阻止刺激警告的蔓延。大学应该赞同美国大学教授联合会关于刺激警告的报告,这份报告写道,“认为学生在课堂中应该受到保护,而不是面对挑战的想法,是把学生当小孩的行为,同时也是反智的”。

Professors should be free to use trigger warnings if they choose to do so, but by explicitly discouraging the practice, universities would help fortify the faculty against student requests for such warnings.

如果出于自愿,教授们应该有使用刺激警告的自由,但是,通过明确地反对刺激警告,大学也能帮助教授拒绝学生的此类要求。

Finally, universities should rethink the skills and values they most want to impart to their incoming students. At present, many freshman-orientation programs try to raise student sensitivity to a nearly impossible level. Teaching students to avoid giving unintentional offense is a worthy goal, especially when the students come from many different cultural backgrounds.

最后,大学应该重新思考他们最想教给学生什么样的技能和价值观。目前,许多面向新生的活动试图把学生的敏感性提升到一个不合理的高度。教导学生避免不小心冒犯别人很有意义,尤其是当学生来自各种不同文化背景的时候。

But students should also be taught how to live in a world full of potential offenses. Why not teach incoming students how to practice cognitive behavioral therapy? Given high and rising rates of mental illness, this simple step would be among the most humane and supportive things a university could do. The cost and time commitment could be kept low: a few group training sessions could be supplemented by Web sites or apps. But the outcome could pay dividends in many ways.

但是学生也应该得到教导,懂得如何生活在一个到处都有潜在冒犯的世界里。为什么不教导学生如何实施认知行为疗法呢?鉴于精神疾病的比率居高不下且仍在上升,把认知行为疗法教给学生就是大学能做的最人道、最有意义的事情了。时间和成本付出都可以很低:只需要几次集体培训课,剩下的就可以靠网站和手机应用来辅助完成,但是学生得到的回报是多方面的。

For example, a shared vocabulary about reasoning, common distortions, and the appropriate use of evidence to draw conclusions would facilitate critical thinking and real debate. It would also tone down the perpetual state of outrage that seems to engulf some colleges these days, allowing students’ minds to open more widely to new ideas and new people. A greater commitment to formal, public debate on campus—and to the assembly of a more politically diverse faculty—would further serve that goal.

例如,建立一套共用的术语,用来描述推理、常见认知扭曲和适当使用证据以引出结论的方法,将会促进批判思维和真正的辩论。这也能缓和近来似乎在大学不断蔓延的愤怒情绪,让学生更容易接受新思想和新人物。在校园内更多地致力于正式、公开的讨论,致力于汇集政见更为多元的教师,会进一步推动这一目标的实现。

Thomas Jefferson, upon founding the University of Virginia, said:

托马斯·杰斐逊在创办弗吉尼亚大学时说:

This institution will be based on the illimitable freedom of the human mind. For here we are not afraid to follow truth wherever it may lead, nor to tolerate any error so long as reason is left free to combat it.

这一机构的根基在于不受限制的思想自由。因为在这里,我们跟随真理,不惧它把我们带到哪里;也无须忍受任何错误,只要允许理智与之自由对抗。

We believe that this is still—and will always be—the best attitude for American universities. Faculty, administrators, students, and the federal government all have a role to play in restoring universities to their historic mission.

我们相信这依旧是——并将一直是——对待美国大学的最佳态度。教师、行政人员,学生,以及联邦政府都有责任让大学回到完成其历史使命的轨道上。

Common Cognitive Distortions

常见的认知扭曲

A partial list from Robert L. Leahy, Stephen J. F. Holland, and Lata K. McGinn’sTreatment Plans and Interventions for Depression and Anxiety Disorders

(2012)

这是来自Robert L. Leahy, Stephen J. F. Holland和Lata K. McGinn的《抑郁症和焦虑症的治疗计划及干预措施》(2012年)的一份部分清单。

1.Mind reading.You assume that you know what people think without having sufficient evidence of their thoughts. “He thinks I’m a loser.”

1.读心术。不需要足够的证据,你就认定自己知道别人想的是什么。“他认为我逊毙了。”

2.Fortune-telling.You predict the future negatively: things will get worse, or there is danger ahead. “I’ll fail that exam,” or “I won’t get the job.”

2.悲观预测。你对未来的预测是消极的:事情会越来越糟糕,或者前方危机四伏。“我考试要不及格了”,或者“我得不到这份工作”。

3.Catastrophizing.You believe that what has happened or will happen will be so awful and unbearable that you won’t be able to stand it. “It would be terrible if I failed.”

3.小题大做。你相信将发生或已发生的事情会糟糕得让人难以忍受。“如果我失败了就太糟糕了。”

4.Labeling.You assign global negative traits to yourself and others. “I’m undesirable,” or “He’s a rotten person.”

4.贴标签。你把自己或其他人归类于某些负面特征。“我不受欢迎”或者“他是个堕落的人。”

5.Discounting positives.You claim that the positive things you or others do are trivial. “That’s what wives are supposed to do—so it doesn’t count when she’s nice to me,” or “Those successes were easy, so they don’t matter.”

5.低估正面信息。你声称自己或者其他人做的有意义的事微不足道。“老婆就应该那个样子——所以她对我好不值一提。”或者“这些成功很容易取得,所以算不上什么成就。”

6.Negative filtering.You focus almost exclusively on the negatives and seldom notice the positives. “Look at all of the people who don’t like me.”

6.负面过滤。你几乎只关注负面信息,很少留意正面信息。“看看那些不喜欢我的人吧。”

7.Overgeneralizing.You perceive a global pattern of negatives on the basis of a single incident. “This generally happens to me. I seem to fail at a lot of things.”

7.以偏概全。你通过一件事就认定整体性的负面模式。“这种事总是发生在我身上。好像我有好多事都干不成。”

8.Dichotomous thinking.You view events or people in all-or-nothing terms. “I get rejected by everyone,” or “It was a complete waste of time.”

8.二元思维。你以非此即彼的方式审视人和事。“我被所有人拒绝”或“这完全是浪费时间”。

9.Blaming.You focus on the other person as the source of your negative feelings, and you refuse to take responsibility for changing yourself. “She’s to blame for the way I feel now,” or “My parents caused all my problems.”

9.迁怒于人。你把其他人当作自己负面情绪的来源,不愿意承担改变自己的责任。“我现在感觉这么糟全都是她的错”或“我所有的问题都是我父母造成的”。

10.What if?You keep asking a series of questions about “what if” something happens, and you fail to be satisfied with any of the answers. “Yeah, but what if I get anxious?,” or “What if I can’t catch my breath?”

10.杞人忧天。你一直问“如果某事发生了怎么办?”,并且对所有答案都不满意。“对,但是如果我变得焦虑怎么办?”或者“如果我喘不过气怎么办?”

11.Emotional reasoning.You let your feelings guide your interpretation of reality. “I feel depressed; therefore, my marriage is not working out.”

11.情绪化推理。你让情感引导你去解读现实。“我很沮丧,所以我的婚姻要完蛋了。”

12.Inability to disconfirm.You reject any evidence or arguments that might contradict your negative thoughts. For example, when you have the thought I’m unlovable,you reject as irrelevant any evidence that people like you. Consequently, your thought cannot be refuted. “That’s not the real issue. There are deeper problems. There are other factors.”

12.无法证伪。你拒绝任何和你的消极想法相抵触的证据或观点。举个例子,你认为“没人喜欢我”,你认为证明别人喜欢你的所有证据都毫不相干。所以,你的思想无法被驳斥。“事情不是这样的。肯定有更深层次的问题,还有其他因素。”

(编辑:辉格@whigzhou)

*注:本译文未经原作者授权,本站对原文不持有也不主张任何权利,如果你恰好对原文拥有权益并希望我们移除相关内容,请私信联系,我们会立即作出响应。

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

订阅

订阅