How Americans Got Red Meat Wrong

美国人对红肉的理解怎么错了

作者:Nina Teicholz @ 2014-06-02

译者:沈沉(@你在何地-sxy)

来源:The Atlantic,

http://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2014/06/how-americans-used-to-eat/371895/

Early diets in the country weren't as plant-based as you might think.

我国的早期饮食并不像你所想的那样以植物为主。

The idea that red meat is a principal dietary culprit has pervaded our national conversation for decades. We have been led to believe that we’ve strayed from a more perfect, less meat-filled past. Most prominently, when Senator McGovern announced his Senate committee’s report, called

Dietary Goals, at a press conference in 1977, he expressed a gloomy outlook about where the American diet was heading.

几十年来,红肉乃饮食首恶的观念一直在我们国家的争论中普遍流行。有人告诉我们,现在我们已经偏离了过去那种更为健康、吃肉更少的传统。最出名的一件事是,在1977年一次媒体发布会上,参议员McGovern代表其所在的参院委员会宣读了名为《膳食指导》的报告。会上他曾对美国人饮食的演变提出了一种非常悲观的展望。

“Our diets have changed radically within the past 50 years,” he

explained, “with great and often harmful effects on our health.” These were the “killer diseases,” said McGovern. The solution, he declared, was for Americans to return to the healthier, plant-based diet they once ate.

“过去50年,我们的饮食发生了剧烈变化,”他解释道,“对我们的健康构成了巨大且往往是有害的影响。”McGovern还说,“这些都是致命的疾病”。他宣称,解决办法就是:美国人要回归他们以前食用的那种更为健康、以植物为主体的饮食。

The justification for this idea, that our ancestors lived mainly on fruits, vegetables, and grains, comes mainly from the USDA “

food disappearance data.” The “disappearance” of food is an approximation of supply; most of it is probably being eaten, but much is wasted, too. Experts therefore acknowledge that the disappearance numbers are merely rough estimates of consumption.

我们的祖先主要吃水果、蔬菜和粮食,这种想法的依据主要来自美国农业部的“食物消散数据”。食物的“消散”只是供给量的近似值;其中大部分大概是被食用了,但也有许多是被浪费了。因此,专家们承认,食物消散数据只是对食物消费量的大概估计。

"I hold a family to be in a desperate way when the mother can see the bottom of the pork barrel."

“我认为,如果一个主妇的猪肉桶都见底了,那这个家庭应该很窘迫。”

The data from the early 1900s, which is what McGovern and others used, are known to be especially poor. Among other things, these data accounted only for the meat, dairy, and other fresh foods shipped across state lines in those early years, so anything produced and eaten locally, such as meat from a cow or eggs from chickens, would not have been included.

McGovern和其他许多人使用的数据来自1900年代,这些数据质量之糟糕是出了名的。不说其他,这些数据只体现了早年间跨州贩卖的肉类、乳品和其他新鲜食物。因此,本地生产并消耗的一切东西,比如牛所产之肉或母鸡所产鸡蛋,都没有计算在内。

And since farmers made up more than a quarter of all workers during these years, local foods must have amounted to quite a lot. Experts agree that this early availability data are not adequate for serious use, yet they cite the numbers anyway, because no other data are available. And for the years before 1900, there are no “scientific” data at all.

由于那时候农牧民在劳动力中占到了四分之一强,因此本地食品总量必定相当大。尽管专家们同意,早期的这一食物可获得性数据并不能够用于严肃场合,可他们还是会引用这些数字,因为没有其他数据可用。至于1900年之前,那就根本没有任何“科学”数据了。

In the absence of scientific data, history can provide a picture of food consumption in the late-18th- to 19th-century in America.

尽管缺乏科学数据,但有关18世纪晚期至19世纪美国的食物消费,历史仍能给我们提供一幅画面。

Early Americans settlers were “indifferent” farmers, according to many accounts. They were fairly lazy in their efforts at both animal husbandry and agriculture, with “the grain fields, the meadows, the forests, the cattle, etc, treated with equal carelessness,” as one 18th-century Swedish visitor described—and there was little point in farming since meat was so readily available.

根据许多记录,早期的美洲殖民者都是“漫不经心”的农牧民。不管是在牲畜饲养,还是在农业种植方面,他们的工作都相当懒惰。正如18世纪一位瑞士访客所说,他们“对于粮田、牧场、森林和牲畜等等,都一样的随意对待”。由于肉食唾手可得,费力农牧也没多大意义。

Settlers recorded the extraordinary abundance of wild turkeys, ducks, grouse, pheasant, and more. Migrating flocks of birds would darken the skies for days. The tasty Eskimo curlew was apparently so fat that it would burst upon falling to the earth, covering the ground with a sort of fatty meat paste. (New Englanders called this now-extinct species the “doughbird.”)

在殖民者的笔下,此地的野生火鸡、鸭子、松鸡、野鸡等等都异常丰富。迁徙的鸟群遮天蔽日,好几天都没完。极北杓鹬美味可口,而且极为肥硕,掉到地上竟然还会炸开,能让泥土表面盖上一层肥腻的肉糊。(新英格兰人将这一现已灭绝的物种称作“面团鸟”。)

In the woods, there were bears (prized for their fat), raccoons, bobolinks, opossums, hares, and virtual thickets of deer—so much that the colonists didn’t even bother hunting elk, moose, or bison, since hauling and conserving so much meat was considered too great an effort. A European traveler describing his visit to a Southern plantation noted that the food included beef, veal, mutton, venison, turkeys, and geese, but he does not mention a single vegetable.

森林里还有熊(因其肉肥而贵重)、浣熊、食米鸟、负鼠、野兔以及跟灌木一样密集的野鹿——猎物如此繁多,以至于殖民者都不愿意费力去捕杀麋鹿、驼鹿或野牛,因为他们觉得要把这么多肉拖回家保存实在太费劲了。一位造访南部某种植园的欧洲旅客提到,当地人的食物包括牛肉、小牛肉、羊肉、鹿肉、火鸡和鹅,他可没有提及任何一种蔬菜。

Infants were fed beef even before their teeth had grown in. The English novelist Anthony Trollope reported, during a trip to the United States in 1861, that Americans ate twice as much beef as did Englishmen. Charles Dickens, when he visited, wrote that “no breakfast was breakfast” without a T-bone steak. Apparently, starting a day on puffed wheat and low-fat milk—our “Breakfast of Champions!”—would not have been considered adequate even for a servant.

小孩子牙都还没长齐,就已经开始喂食牛肉。英国小说家Anthony Trollope于1861年造访美国后曾说,美国人所吃牛肉是英国人的两倍。Charles Dickens访美后则写道,如果没有一块T骨牛排,“早餐就不成其为早餐”。显然,即便是对仆人而言,早上吃点膨化小麦和低脂牛奶——我们的“早餐之冠”——也是不够的。

Indeed, for the first 250 years of American history, even the poor in the United States could afford meat or fish for every meal. The fact that the workers had so much access to meat was precisely why observers regarded the diet of the New World to be superior to that of the Old.

实际上,在美国人最初的250年历史中,即便是国内最穷的人,每顿也能吃得起肉或者鱼。劳动者如此容易吃上肉,这一事实正是当时的观察者认为新大陆饮食优于旧大陆的原因所在。

“I hold a family to be in a desperate way when the mother can see the bottom of the pork barrel,” says a frontier housewife in James Fenimore Cooper’s novel

The Chainbearer.

“我认为,如果一个主妇的猪肉桶都见底了,那这个家庭应该很窘迫。”在James Fenimore Cooper的小说《戴锁链的人》中,一位西部边疆家庭主妇如此说道。

In the book

Putting Meat on the American Table, researcher Roger Horowitz scours the literature for data on how much meat Americans actually ate. A

survey of 8,000 urban Americans in 1909 showed that the poorest among them ate 136 pounds a year, and the wealthiest more than 200 pounds.

研究者Roger Horowitz在其著作《把肉食端上美国餐桌》中四处搜求文献,想要找到美国人到底食用多少肉食的数据。1909年针对8000位美国城市居民的一份调查显示,受访者中最贫穷的每年食肉136磅,最富裕的则超过200磅。

A food budget published in the

New York Tribune in 1851 allots two pounds of meat per day for a family of five. Even slaves at the turn of the 18th century were allocated an average of 150 pounds of meat a year. As Horowitz concludes, “These sources do give us some confidence in suggesting an average annual consumption of 150–200 pounds of meat per person in the nineteenth century.”

在1851年发表于《纽约论坛报》上的一份食品预算中,一个五口之家每天可以得到2磅肉。在18世纪初,即便是奴隶,每年平均也可以得到150磅肉。正如Horowitz所总结的,“这些资料让我们可以多少有点自信地推测:在19世纪,每年的人均肉食消耗量平均大概是150至200磅。”

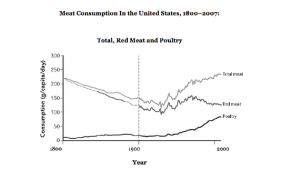

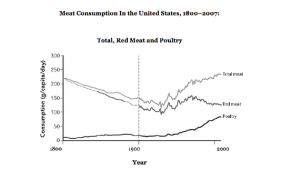

About 175 pounds of meat per person per year—compared to the

roughly 100 pounds of meat per year that an average adult American eats today. And of that 100 pounds of meat, about half is poultry—chicken and turkey—whereas until the mid-20th century, chicken was considered a luxury meat, on the menu only for special occasions (chickens were valued mainly for their eggs).

也就是说,每人每年大概175磅肉。与之对比,平均每个成年美国人现在每年大概食肉100磅。在这100磅肉中,大概有一半是禽肉——即鸡肉和火鸡。与之相比,在20世纪中叶以前,鸡肉一直被视作为奢侈肉类,只在特殊场合才能进菜谱(母鸡因为能生蛋而价值颇高)。

Yet this drop in red meat consumption is the exact opposite of the picture we get from public authorities. A recent USDA report says that our consumption of meat is at a “

record high,” and this impression is repeated in the media.

然而,红肉消耗量下降这一事实,与我们从公共权威那里得到的印象大相径庭。美国农业部近期的一份报告说,我们的肉食消耗量正处于“历史最高记录”,而且这一说法还在媒体上反复流传。

It implies that our health problems are associated with this rise in meat consumption, but these analyses are misleading because they lump together red meat and chicken into one category to show the growth of meat eating overall, when it’s just the chicken consumption that has gone up astronomically since the 1970s. The wider-lens picture is clearly that we eat far less red meat today than did our forefathers.

这一说法暗示,我们的健康问题与肉食消耗量增加有关。但是这种分析是误导性的,因为它们将红肉和鸡肉并为一类、混为一谈,以此来证明总体食肉量的增加。实际上,只有鸡肉消耗量才于1970年代以后出现了极大增长。把视野放宽的话,图景很清晰:今天我们所食用的红肉量远远不能与我们的祖先相比。

Meanwhile, also contrary to our common impression, early Americans appeared to eat few vegetables. Leafy greens had short growing seasons and were ultimately considered not worth the effort. And before large supermarket chains started importing kiwis from Australia and avocados from Israel, a regular supply of fruits and vegetables could hardly have been possible in America outside the growing season.

同时,还有一件事也与我们通常的印象相反,早期美国人似乎蔬菜吃得很少。绿叶蔬菜生长季节短,人们最终觉得它们不值得费心种植。而且在大型连锁超市为我们从澳大利亚进口猕猴桃、从以色列进口鳄梨之前,只要生长季节一过,要想在美国实现果蔬的常规供应就几乎不可能了。

Even in the warmer months, fruit and salad were avoided, for fear of cholera. (Only with the Civil War did the canning industry flourish, and then only for a handful of vegetables, the most common of which were sweet corn, tomatoes, and peas.)

即便是在温暖的月份,因为担心霍乱,人们也会避开水果和生吃蔬菜。(罐头行业只是内战以后才开始兴盛起来,而且那也只是罐装少量蔬菜,最常见的主要有甜玉米、西红柿和豌豆。)

So it would be “incorrect to describe Americans as great eaters of either [fruits or vegetables],”

wrote the historians Waverly Root and Richard de Rochemont. Although a vegetarian movement did establish itself in the United States by 1870, the general mistrust of these fresh foods, which spoiled so easily and could carry disease, did not dissipate until after World War I, with the advent of the home refrigerator. By these accounts, for the first 250 years of American history, the entire nation would have earned a failing grade according to our modern mainstream nutritional advice.

所以,历史学家Waverly Root和Richard de Rochemont说,“认为美国人是水果或蔬菜的大量食用者,这种说法是错的”。尽管美国在1870年确实出现了一次素食运动,但美国人对这类非常容易腐烂、可能携带疾病的新鲜食物普遍存疑,这种疑虑直到一战以后随着家用冰箱的出现方才消散。根据这些资料,在美国历史的头250年,要是参照我们现在主流的营养学建议,整个国家得分都会不及格。

During all this time, however, heart disease was almost certainly rare. Reliable data from death certificates is not available, but other sources of information make a persuasive case against the widespread appearance of the disease before the early 1920s.

然而,在整个这一时期,心脏病几乎难得一见。基于死亡证明的可靠数据现在还没有,但其他方面的信息令人信服地证明,在1920年代前期以前,心脏病并没有大面积出现。

Fat intake rose 12 percent from 1909 to 1961, but it was owing to an increase in the supply of vegetable oils, which had recently been invented.

从1909年至1961年,脂肪摄入量提高了12%,但这是因为人类新近发明了植物油,其供给增加了。

Austin Flint, the most authoritative expert on heart disease in the United States, scoured the country for reports of heart abnormalities in the mid-1800s, yet reported that he had seen very few cases, despite running a busy practice in New York City. Nor did William Osler, one of the founding professors of Johns Hopkins Hospital, report any cases of heart disease during the 1870s and eighties when working at Montreal General Hospital.

19世纪中期,美国最权威的心脏病专家Austin Flint曾在全国上下搜集心脏异常病例的报告,最后却说案例寥寥无几,尽管他当时在纽约的生意非常繁忙。约翰·霍普金斯医院的创始教授之一William Osler,在他于1870年代及1880年代在蒙特利尔综合医院工作期间,也未提及任何心脏病案例。

The first clinical description of coronary thrombosis came in 1912, and an authoritative textbook in 1915,

Diseases of the Arteries including Angina Pectoris, makes no mention at all of coronary thrombosis. On the eve of World War I, the young Paul Dudley White, who later became President Eisenhower’s doctor, wrote that of his 700 male patients at Massachusetts General Hospital, only four reported chest pain, “even though there were plenty of them over 60 years of age then.”

关于冠状动脉血栓的首份临床描述出现于1912年,而1915年的一本权威教材——《动脉疾病及心绞痛》——则根本没有提及冠状动脉血栓。一战前夜,年轻的Paul Dudley White(后来曾为艾森豪威尔总统担任医生)写道,他在马萨诸塞综合医院的700名男性病人中,只有4个报告有胸痛,“尽管他们中许多人已经过了60岁年纪。”

About one fifth of the U.S. population was over 50 years old in 1900. This number would seem to refute the familiar argument that people formerly didn’t live long enough for heart disease to emerge as an observable problem. Simply put, there were some 10 million Americans of a prime age for having a heart attack at the turn of the 20th century, but heart attacks appeared not to have been a common problem.

1900年,美国人口中大约有五分之一超过50岁。有种常见的论调认为,以前的人寿命不够长,所以心脏病根本还来不及成为一个显著问题。不过上述数字似乎能够驳斥这种论调。简单地说,在20世纪初,大约有1000万美国人已经到了容易发生心脏病的年纪,但那时候心脏病似乎并不是一个常见问题。

Ironically—or perhaps tellingly—the heart disease “epidemic” began after a period of exceptionally

reduce meat eating. The publication of

The Jungle, Upton Sinclair’s fictionalized exposé of the meatpacking industry, caused meat sales in the United States to fall by half in 1906, and they did not revive for another 20 years.

讽刺地是,或者说颇能说明问题的是,心脏病的“流行”发生在食肉量出现异常减少之后。Upton Sinclair出版的《屠宰场》一书以小说形式对肉类加工业进行了揭露曝光,导致1906年美国肉类销售量直接减半,此后20年都没能恢复。

In other words, meat eating went down just before coronary disease took off. Fat intake did rise during those years, from 1909 to 1961, when heart attacks surged, but this 12 percent increase in fat consumption was not due to a rise in animal fat. It was instead owing to an increase in the supply of vegetable oils, which had recently been invented.

换句话说,食肉量的减少恰好发生于冠心病猛增之前。1909年到1961年期间,当心脏病出现激增时,脂肪摄入量确实也增加了,但是脂肪消耗量上增加的这12%并不来自动物脂肪的增加。相反,它来自植物油供给的增加,后者新近才被发明出来。

Nevertheless, the idea that Americans once ate little meat and “mostly plants”—espoused by McGovern and a multitude of experts—continues to endure. And Americans have for decades now been instructed to go back to this earlier, “healthier” diet that seems, upon examination, never to have existed.

尽管如此,美国人过去吃肉很少、“主要吃植物”的观念——McGovern和许多专家都信奉这一点——还在继续流传。而且,过去几十年,美国人接受的指导一直是,他们应该回归这种更早、“更健康”的饮食。只不过,经验证发现,这种饮食习惯从未存在过。

(编辑:辉格@whigzhou)

*注:本译文未经原作者授权,本站对原文不持有也不主张任何权利,如果你恰好对原文拥有权益并希望我们移除相关内容,请私信联系,我们会立即作出响应。

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

订阅

订阅