【2017-10-17】

@whigzhou: 去年我在谈论当代低生育率问题时,曾提出一个猜想:传统文化对婚育行为所创造的强大约束,或许弱化了部分人类的本能生育倾向,结果是,即便这方面本能已有所削弱的个体,也并不比其他人少生育,于是,当文化约束在现代迅速解除时,生育率便急剧下降。(当然,这里说的只是需求侧,成本侧还有诸多原因,对后者已经有了足够多的分析,我就不啰嗦了)

@whigzhou: 最初产生这个念头是在若干年前考虑文化宽容对(more...)

【2017-10-17】

@whigzhou: 去年我在谈论当代低生育率问题时,曾提出一个猜想:传统文化对婚育行为所创造的强大约束,或许弱化了部分人类的本能生育倾向,结果是,即便这方面本能已有所削弱的个体,也并不比其他人少生育,于是,当文化约束在现代迅速解除时,生育率便急剧下降。(当然,这里说的只是需求侧,成本侧还有诸多原因,对后者已经有了足够多的分析,我就不啰嗦了)

@whigzhou: 最初产生这个念头是在若干年前考虑文化宽容对(more...)

【2017-05-04】

伊斯兰世界的平均智商大概在82-85之间,低于欧洲和东亚不止一个标准差,对于一个早已文明化、社会结构也足够复杂的地区,这是件有点蹊跷的事情,其选择机制一定其他文明社会十分不同,不知道多妻制,奴隶的广泛使用,权力继承模式,等级结构的特征,分别在其中起了什么作用没有。

【2017-09-09】

@tertio 有一个猜想,两个人之间的语言交流,信息密度越大的(用更短的句子就能表达同样的意思),两个人关系就越近。最近的时候,就是不需要语言啦,表情就够了。但怎么测量信息密度倒是个不好解决的问题。

@whigzhou: 文化距离越近,1)共享的背景知识越多,2)共享的索引机制越精妙,1和2皆可缩短某一表达所需句子长度。

【2017-08-31】

综合185份研究的数据显示,1973-2011年间,西方世界男性平均精子产量下降59.3%,浓度下降52.4%,这很明显是西方社会整体阴柔化的生理表现。

或许并非巧合的是,这四十年西方各国没有经历任何重大战争,在此期间经历过大战(或越战之类中型战争)的人口逐渐被未经历任何战争的人口替代。

说起战争与文化的关系,想到另一件事情,美国四次大觉醒运动的后三次,完美对应三次重大战争:独立战争,内战,二(more...)

【2016-07-21】

很少有地方能像移民英语班那样让你一下子认识来自众多民族的人,而且还都有所交流,我的班里,上学期有——

一个索马里人,是5个孩子的妈,说话音乐感很好,手掌上常有各种彩绘,是医疗系统的重度使用者,从她那儿常能听到各种有关看医生的事情,

还不确定,因为有几次看到的花纹好像不一样也可能是我记错,再观察观察 //@熊也會死麼:手掌上的彩绘确定不是纹身?

一个苏丹女孩,19岁,又瘦又高,典型东非牧民身材,很腼腆,不太说话,来了两三次后来就没见过,

一个伊拉克大妈,一儿一女,孩子都上学了打算找工作,所以来学英语(这也是1/3左右的学生来上课的动机)(more...)

New Study: Millennials Don’t Deserve to Be Called the Hookup Generation

最新研究:千禧一代配不上『勾搭世代』的盛名

作者:Jessie Geoffray @ 2016-08-02

翻译:Drunkplane(@Drunkplane-zny)

校对:Drunkplane(@Drunkplane-zny),龟海海

来源:PLAYBOY,http://www.playboy.com/articles/millennials-the-hookup-generation

Remember when Vanity Fair published an article last year gleefully proclaiming we were at the dawn of a “dating apocalypse” and promiscuous millennials and their newfangled internet-enabled devices were on their way to destroying sex and romance as we know it? And remember when Tinder, affronted by this suggestion of base crassness, took to Twitter to unleash a savage, epic rant directed at the magazine and its indelicate fingering of the app as a prime catalyst of our rude new world?

还记得《名利场》去年发表的文章吗?它兴高采烈地宣称我们正迎来“约炮盛世”,谁都知道,性关系混乱的千禧一代和他们时髦的互联网设备正在破坏着性和浪漫。Tinder【译注:一款流行的交友软件】认为文章暗示自己粗俗不堪,大为光火,在推特上火力全开,大骂《名利场(more...)

-@VanityFair Little known fact: sex was invented in 2012 when Tinder was launched. — Tinder (@Tinder) August 11, 2015 -《名利场》知道个屁:性是在2012年Tinder面市时被发明的。 —Tinder (@Tinder) 在2015年8月11号的推文Tinder wasn’t the only collateral damage in journalist Nancy Jo Sales’s nearly 7,000-word piece: a widely circulated paper from Archives of Sexual Behavior claiming millennials have fewer sex partners than previous generations was bizarrely relegated to a dismissive parenthetical. Now, roughly a year later, the authors of that study are back and re-inviting us to the lively party that is speculating about millennials, and their perceived failings, on the internet. Tinder不是Nancy Jo Sales那篇7000字文章的唯一受害者:《性行为档案》上一篇广为转载的论文也莫名其妙地被她在文章注释里轻蔑地嘲讽了一番。论文宣称比起前面几代人,千禧一代的性伴侣更少。现在,大概一年之后,这项研究的作者再次站出来,邀请我们加入这场网上大讨论,审视千禧一代和他们的堕落。 The new Archives of Sexual Behavior study uses data from the General Social Survey—a nationally representative sample of American adults aged 18 to 96, conducted biannually since 1989—to examine patterns of sexual inactivity over time. The analysis shows that not only are people born in the 1980s and 1990s reporting fewer sexual partners than GenX’ers or Baby Boomers, but also that the marked change in sexual inactivity is independent of the effects of age or time period. In other words, it can be attributed to a generation alone. 《性行为档案》的这项新研究采用了“综合大调查”——一项自1989年以来每两年举行一次的调查,其样本代表了全美范围内18至96岁的成人——的数据来研究性行为不活跃程度(sexual inactivity)随时间的变化。研究发现,不只是80后和90后们比起X一代【译注:约略指1965年至1980年出生的人】和婴儿潮一代【译注:约略指1946年至1964年出生的人】拥有更少的性伴侣,而且这种性行为不活跃程度的显著变化同年龄和时代没有关系。换句话说,原因可能仅仅出在这一代人身上。 “Americans born in the 1990s were more likely to be sexually inactive in their early 20s.” “出生于1990年代的美国人更可能在20岁出头时表现得性行为不活跃。” The numbers are significant: Fifteen percent of millennials born in the 1990s and between 20 and 24 years old reported having no sexual partners since the age of 18. That’s more than double the six percent of GenX’ers born in the 1960s who reported having no sexual partners during the same age ranges. 数字颇能说明问题:出生于90年代且年龄在20至24岁之间的千禧一代中,有15%的人报告说他们从18岁起就没有性伙伴。这个数字同出生在60年代的X一代相比翻了一倍——相比之下,只有6%的X一代在这个年龄段报告自己没有性伙伴。 These comparisons are purely descriptive in the sense that they give us clues about what, exactly, defines the millennial generation: Americans born in the 1990s were more likely to be sexually inactive in their early 20s; women were more likely to be sexually inactive than men; and people who did not attend college were more likely to be sexually inactive compared to those who did. 到底是什么定义了千禧一代,这些对比给出的线索是纯粹描述性的:90年代出生的美国人在他们20多岁时性活跃程度可能更低;女性性活跃程度低于男性;没有上大学的人性活跃程度低于那些上过大学的人。 “We can say ‘Here’s the trend’ and isolate it down to saying it’s a generational thing, but we can’t exactly say why,” says Ryne Sherman, co-author of the study and associate professor of psychology in the Charles E. Schmidt College of Science at Florida Atlantic University. “我们可以说‘趋势便是如此’,然后孤立地看待这个问题并认为这是年代更替的自然结果,但我们却说不出来原因何在。”Ryne Sherman说道,她是该研究报告的共同作者,佛罗里达大西洋大学查理•施密特科学学院的心理学副教授。 Potential explanations explored in the paper include the rise of internet pornography, the economic downturn and its role in delaying millennials’ independence from their parents (think less independent lodgings to help facilitate sex), and the possibility that millennials are indeed hooking up with more partners, but engaging in penetrative sex less often. The explanation Sherman favors is that apps like Tinder—and the rise of the internet itself—provide an outlet for people to connect and be social without needing to pursue sex in real life. 论文讨论过的可能解释包括:网络色情的泛滥,经济下滑及其在推迟年轻人与父母分居上的作用(想想没有自己的房子多么不利于“房事”吧),以及这样一种可能:千禧一代确实有更多鬼混的伙伴,但更少进行插入式的性交。Sherman偏爱的一种解释是,像Tinder这样的应用软件以及互联网的兴起让人们能够相互联系和交往,却不必在真实生活中追求性关系。 Of course, another possible explanation is that different generations interpreted the survey’s key question—“Since the age of 18, how many sexual partners have you had?”—differently. 当然,另一个可能的解释是:不同年代的人对调查的核心问题——“从你18岁起,你有过多少性伙伴”——有着不同的理解。 Sherman thinks this is highly unlikely, saying that if interpretation of the phrase “sexual partners” was changing, it would show up in the period effect (i.e., everybody living in that time would experience a change in the meaning of the term) and not just the generational effect. It didn’t. Sherman 认为这几乎不可能,他说如果对“性伙伴”这个词的理解一直在变,那它就会体现在时间效应上(比如,生活在某一时间段的每个人都会感受到词意的变化),而不仅仅体现在代际效应上。实际上并没有。 But, I’d challenge Sherman to have a conversation with my grandmother about “sexual partners” and see if he still feels we’re all still on the same page about words and what they mean. 但是,我倒想请Sherman同我的奶奶谈谈“性伙伴”,看看到时候他是否仍坚持认为人们对该词的理解并未改变。 (编辑:辉格@whigzhou) *注:本译文未经原作者授权,本站对原文不持有也不主张任何权利,如果你恰好对原文拥有权益并希望我们移除相关内容,请私信联系,我们会立即作出响应。

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

‘We Hillbillies Have Got to Wake the Hell Up': Review of Hillbilly Elegy

“我们这些山巴佬该醒醒了”——《山乡挽歌》书评

A family chronicle of the crackup of poor working-class white Americans.

一份贫穷糟糕美国白人工薪阶层的家庭编年史

作者:Ronald Bailey @ 2016-07-29

翻译:Drunkplane(@Drunkplane-zny)

校对:babyface_claire

来源:reason.com,http://reason.com/archives/2016/07/29/we-hillbillies-have-got-to-wake-the-hell

【编注:hillbilly和redneck、yankee、cracker一样,都是对美国某个有着鲜明文化特征的地方群体的蔑称,本文译作『山巴佬』】

Read this remarkable book: It is by turns tender and funny, bleak and depressing, and thanks to Mamaw, always wildly, wildly profane. An elegy is a lament for the dead, and with Hillbilly Elegy Vance mourns the demise of the mostly Scots-Irish working class from which he springs. I teared up more than once as I read this beautiful and painful memoir of his hillbilly family and their struggles to cope with the modern world.

阅读这本非凡之作的感受时而温柔有趣,时而沮丧压抑,而且,亏了他的祖母,还往往十分狂野,狂野地对神不敬。挽歌是对死人的悼念。Vance用《山乡挽歌》缅怀了苏格兰-爱尔兰裔工人阶级的衰亡,他自己便出身于此阶级。这本书描写了他的乡下家庭及其在现代社会中的挣扎,在阅读这本美丽而痛苦的回忆录时,我几度流泪。

Vance grew up poor with a semi-employed, drug-addicted mother who lived with a string of five or six husbands/boyfrie(more...)

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

Why are we so afraid to leave children alone?

为什么我们害怕让孩子独处?

作者:Pat Harriman & Heather Ashbach, UC Irvine @ 2016-08-23

译者:明珠(@老茄爱天一爱亨亨更爱楚楚)

校对:babyface_claire(@许你疯不许你傻)

来源:UC, http://universityofcalifornia.edu/news/why-are-we-so-afraid-leave-children-alone

Leaving a child unattended is considered taboo in today’s intensive parenting atmosphere, despite evidence that American children are safer than ever. So why are parents denying their children the same freedom and independence that they themselves enjoyed as children?

在今天这种强化父母责任的社会氛围中,留下孩子无人照看被视为禁忌,虽然有证据表明美国孩子比以往任何时候都更安全。那么,为什么父母拒绝孩子拥有从前他们自己是孩子时享受的同样的自由和独立呢?

A new study by University of Calif(more...)

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

声望与权力

辉格

2016年12月24日

建立与维护自己的声望(prestige)是人类行为的一大动机,经济学家早已注意到,这一动机是许多消费行为背后的推动力,它构成了某些门类商品的主要甚至唯一的价值基础,而且看来有着牢固的心理基础和古老的渊源。

考古学家发现,用于此类目的的物品——被称为声望品(prestige goods)——在远古人类遗存中占了很大比例,是识别社会复杂程度的重要线索;对声望品的追逐也是推动早期手工业和贸易活动的主要动力,甚至像青铜器制造这样里程碑式的技术进步,最初也是由声望追逐者的需求所促成。

当然,拥有声望品更多的是对既已建立的声望的展示,而非声望本身,这一展示所传达的信息大约包括:我具备不俗的才智与鉴别力,据此取得了相当成就,过着一份体面生活,赢得了其他社会成员的尊重,建立了良好的社会关系,甚至不乏仰慕与追随者,我对他们慷慨大方,乐于出手相助,总之,我是一个有价值的交往对象。

高声望者不仅有着出色的个人禀赋,更重要的是(用社会学家的话说)拥有雄厚的社会资本(social capital),正是后者赋予他们在社会交往中的吸引力,也让他们愿意投入资源去经营和维护社会关系,因为首先,社交魅(more...)

封侯拜爵的神仙们

辉格

2016年12月11日

中国民间信仰以其神仙繁多而著称,宋代仅湖州一地的寺观祠庙里供奉的神祗,有史料可查者即有92个,扣除名号重复者,还有50多个,粗略估算,全国各地的神祗数量大约介于乡镇数和村庄数之间,看来古代中国人『积极造神,见神即拜』的名声并非虚浪。

如此多神仙得到敬拜,还要归功于神仙来源的多样化,和大众在神仙制造方式上的创造性;早期神祗来源大致和其他文化相仿,比如司掌某种自然力的自然神,或者被认定为某一族群共同祖先的始祖神,然而自中古以降,一种新型神祗开始大量涌现。

这些新神都是不久前还生活于人世的真实人物,因某种显赫成就或奇特经历而被认为拥有神力;认定神力的入门标准很低——担任过高官,参加过某次战役,遭受过冤屈,或者离奇死亡——总之,任何在大众眼里有点特别的地方(more...)

(本文删节版发表于《长江日报·读周刊》)

塑造行为的多重机制

辉格

2016年12月2日

人的行为方式千差万别且变化多端,这也体现在我们描绘行为的形容词的丰富性上:羞涩,奔放,畏缩,鲁莽,克制,放纵,粗野,优雅,勤勉,懒散,好斗,随和……这些词汇同时也被用来描绘个体性格,有些甚至用来辨识文化和民族差异,由此可见,尽管人类行为丰富多变,却仍可识别出某些稳定而持久的模式。

那么,究竟是哪些因素,经由何种过程,塑造了种种行为模式呢?在以往讨论中,流行着一种将遗传和环境影响对立两分的倾向,仿佛这两种因素是各自独立起作用的,最终结果只是两者的线性叠加,就像调鸡尾酒,人们关注的是各种原料的配比,五勺基因,两勺家庭,两勺学校,再加一勺『文化』,一个活蹦乱跳的文明人就出炉了。

这种将成长中的孩子视为受影响者或加工对象的视角,是不得要领的,实际上,成长是一个主动学习的过程,基因和环境的关系更像软件中代码和数据输入的关系,基因编码引导个体从环境中采集数据,以便配置自身的行为算法,把代码和数据放一起搅一搅不可能得到想要的功能,在软件工程中,也没人会谈论代码和数据对算法表现分别有多大比例的影响。

BOOK REVIEW: ALBION’S SEED

书评:《阿尔比恩的的种子》

作者:SCOTT ALEXANDER @ 2016-04-27

译者:Tankman

校对:沈沉(@沈沉-Henrysheen)

来源:http://slatestarcodex.com/2016/04/27/book-review-albions-seed/

I.

Albion’s Seed by David Fischer is a history professor’s nine-hundred-page treatise on patterns of early immigration to the Eastern United States. It’s not light reading and not the sort of thing I would normally pick up. I read it anyway on the advice of people who kept telling me it explains everything about America. And it sort of does.

《阿尔比恩的种子》是历史学教授David Fischer 所作的九百页专著【校注:阿尔比恩,英国旧称,据说典出海神之子阿尔比恩在岛上立国的神话】。该书讨论了美国东部地区的早期移民的模式。阅读此书并不轻松,而且一般我也不会挑选这种书来读。但不管如何,我读完了。这是因为有人向我推荐此书,他们不断告诉我它能解释关于美国的一切。而某种程度上,此书做到了这点。

In school, we tend to think of the original American colonists as “Englishmen”, a maximally non-diverse group who form the background for all of the diversity and ethnic conflict to come later. Fischer’s thesis is the opposite. Different parts of the country were settled by very different groups of Englishmen with different regional backgrounds, religions, social classes, and philosophies. The colonization process essentially extracted a single stratum of English society, isolated it from all the others, and then plunked it down on its own somewhere in the Eastern US.

在学校,我们倾向于把初代北美殖民者看作是“英国人”,这是一个最不多元化的群体,并且构成了后来所有的多元性和种族冲突的背景。Fischer的论述则与此相反。这个国家的不同地区被非常不同的英国人群体开拓。这些群体有着不同的地区背景,宗教,社会阶级和哲学。殖民化过程其实是提取了英国社会的某个单一阶层,令其与其他阶层隔绝,而后在美国东部的某个地方打上该群体深深的烙印。

I used to play Alpha Centauri, a computer game about the colonization of its namesake star system. One of the dynamics that made it so interesting was its backstory, where a Puerto Rican survivalist, an African plutocrat, and other colorful characters organized their own colonial expeditions and competed to seize territory and resources. You got to explore not only the settlement of a new world, but the settlement of a new world by societies dominated by extreme founder effects.

我曾玩过电脑游戏《南门二》。这游戏是关于与游戏同名的星系的殖民活动的。游戏如此有趣的一个因素是其故事背景:一个波多黎各生存狂,一个非洲财阀,以及其他有色人种角色组织了他们自己的殖民探险,相互竞争,来占领领土和资源。你能探索的,不单单只是对新世界拓殖,而且是那种受极端奠基者效应支配的社会对新世界的拓殖。

What kind of weird pathologies and wonderful innovations do you get when a group of overly romantic Scottish environmentalists is allowed to develop on its own trajectory free of all non-overly-romantic-Scottish-environmentalist influences? Albion’s Seed argues that this is basically the process that formed several early US states.

当一群过度浪漫的苏格兰环保主义者被允许自由发展,不受其他群体影响时,你能得到什么样怪异的社会失序或是伟大创新呢?《阿尔比恩的种子》认为这基本上是早期美国的某几个州形成的过程。

Fischer describes four of these migrations: the Puritans to New England in the 1620s, the Cavaliers to Virginia in the 1640s, the Quakers to Pennsylvania in the 1670s, and the Borderers to Appalachia in the 1700s.

Fischer描述了这些移民中的四种:在1620年代来到新英格兰地区的清教徒,在1640年代来到弗吉尼亚的“骑士党”,在1670年代来到宾夕法尼亚的贵格会,以及1700年代来到阿巴拉契亚山地的边民【校注:指英格兰和苏格兰交界地区的人】。

II.

A: The Puritans

A:清教徒

I hear about these people every Thanksgiving, then never think about them again for the next 364 days. They were a Calvinist sect that dissented against the Church of England and followed their own brand of dour, industrious, fun-hating Christianity.

我在每个感恩节都听说过这群人,而后在接下来的364天,就再也没有想起过他们。他们是一个加尔文宗派,对英国国教会持异议,而且遵从他们特有的严厉,勤奋,厌恶享乐的基督教伦理。

Most of them were from East Anglia, the part of England just northeast of London. They came to America partly because they felt persecuted, but mostly because they thought England was full of sin and they were at risk of absorbing the sin by osmosis if they didn’t get away quick and build something better. They really liked “city on a hill” metaphors.

他们中的大多数,来自东英吉利,是位于伦敦东北方向的一个地区。他们来到美国,部分是因为他们感到被迫害,但是大部分原因是他们觉得英国充满了罪恶,如果不尽快离开并且构建更好的生活,他们就面临被罪恶渗透的风险。他们真是非常喜爱“山巅之城”这个比喻。

I knew about the Mayflower, I knew about the black hats and silly shoes, I even knew about the time Squanto threatened to release a bioweapon buried under Plymouth Rock that would bring about the apocalypse. But I didn’t know that the Puritan migration to America was basically a eugenicist’s wet dream.

我知道五月花,我知道清教徒的黑帽和有些滑稽的皮鞋,我甚至知道印第安领袖Squanto曾威胁释放普利茅斯岩石之下那能够带来末日灾难的生物武器。但是我不知道清教徒移民美国基本上是个优生学的春梦。

Much like eg Unitarians today, the Puritans were a religious group that drew disproportionately from the most educated and education-obsessed parts of the English populace. Literacy among immigrants to Massachusetts was twice as high as the English average, and in an age when the vast majority of Europeans were farmers most immigrants to Massachusetts were skilled craftsmen or scholars. And the Puritan “homeland” of East Anglia was a an unusually intellectual place, with strong influences from Dutch and Continental trade; historian Havelock Ellis finds that it “accounts for a much larger proportion of literary, scientific, and intellectual achievement than any other part of England.”

清教徒这个宗教团体很像今天的唯一神教派,其成员中很多是受过最好教育、最痴迷于教育的英国民众。来到马萨诸塞的移民,其拥有读写能力的比例,是英国平均水平的两倍;在一个大部分欧洲人还是农夫的时代,大部分马萨诸塞的移民是熟练技工或学者。而清教徒在东英吉利的“故土”则是个文教很发达的地方,受到荷兰和大陆贸易的强烈影响;历史学家Havelock Ellis发现,“相比英国的其他任何地区,该地很大程度上以文艺,科学和知识成就著称。”

Furthermore, only the best Puritans were allowed to go to Massachusetts; Fischer writes that “it may have been the only English colony that required some of its immigrants to submit letters of recommendation” and that “those who did not fit in were banished to other colonies and sent back to England”. Puritan “headhunters” went back to England to recruit “godly men” and “honest men” who “must not be of the poorer sort”.

而且,只有最好的清教徒,才能被允许来到马萨诸塞;Fischer写道,“这也许是唯一要求部分移民出具推荐信的英国殖民地”,而且“不适合该地的移民,则被放逐到其他殖民地,或是送回英国。”清教徒“猎头”回到英国去招募“虔敬的人”和“诚实的人”,这些人“绝对不能是阶层较低的那一类”。

INTERESTING PURITAN FACTS:

关于清教徒的一些有趣事实:

1. Sir Harry Vane, who was “briefly governor of Massachusetts at the age of 24”, “was so rigorous in his Puritanism that he believed only the thrice-born to be truly saved”.

Harry Vane先生“在24岁时曾短期担任马萨诸塞殖民地的长官”。“他践行清教徒伦理十分严格,以至于相信只有第三次重生的人才能够得救”。

2. The great seal of the Massachusetts Bay Company “featured an Indian with arms beckoning, and five English words flowing from his mouth: ‘Come over and help us’”

马萨诸塞湾公司的大印上刻着“一个印第安人在招手,从他嘴里喊出五个词:‘来帮助我们’”。

3. Northern New Jersey was settled by Puritans who named their town after the “New Ark Of The Covenant” – modern Newark.

新泽西北部的清教徒开拓者把他们的镇起名为“新约柜”————即如今的纽瓦克

4. Massachusetts clergy were very powerful; Fischer records the story of a traveller asking a man “Are you the parson who serves here?” only to be corrected “I am, sir, the parson who ruleshere.”

马萨诸塞的牧师有很大权力;Fischer记录了一个故事:一个旅行者问一个男人“您(more...)

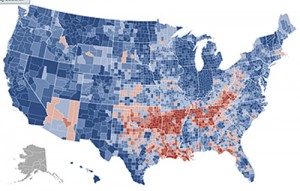

这是2012年总统大选在郡层面的投票模式的地图。蓝色区域在南方精确地分布在大量非裔美国人聚居的所谓“黑带”上。在中西部的蓝色基本上是大城市。除了这些,选民主党的人只有新英格兰人(支持度很高!)和宾州德拉威尔河谷地区。

In fact, you can easily see the distinction between the Delaware Valley settled by Quakers in the east, and the backcountry area settled by Borderers in the west. Even the book’s footnote about how a few Borderers settled in the mountains of New Hampshire is associated with a few spots of red in the mountains of New Hampshire ruining an otherwise near-perfect Democratic sweep of the north.

事实上,你能一眼看出,贵格会开拓的东部德拉威尔河谷和边民开拓的西部区域之间的区别。即便是书中脚注提到的少量边民移居新罕布尔州群山也能对应图中新罕布尔州群山中的几个红点,如果不是这几个红点,民主党在北方就拥有了完美的全胜。

One anomaly in this story is a kind of linear distribution of blue across southern Michigan, too big to be explained solely by the blacks of Detroit. But a quick look at Wikipedia’s History of Michigan finds:

这个故事中的一个异常就是在南密歇根存在一种线性分布的蓝色,面积太大,不能仅用底特律的黑人来解释。但是快速浏览维基百科上密歇根的历史条目就会发现:

In the 1820s and 1830s migrants from New England began moving to what is now Michigan in large numbers (though there was a trickle of New England settlers who arrived before this date). These were “Yankee” settlers, that is to say they were descended from the English Puritans who settled New England during the colonial era….Due to the prevalence of New Englanders and New England transplants from upstate New York, Michigan was very culturally contiguous with early New England culture for much of its early history…The amount with which the New England Yankee population predominated made Michigan unique among frontier states in the antebellum period. Due to this heritage Michigan was on the forefront of the antislavery crusade and reforms during the 1840s and 1850s.

在1820年代到1830年代,来自新英格兰的移民大量移居到今日的密歇根(虽然有少量新英格兰开拓者在之前就移居此地)。这些是“扬基”开拓者,这意味着他们是在殖民地时期住在新英格兰的英国清教徒的后裔……因为新英格兰人众多,以及从纽约上州移入的新英格兰人,在它早期历史的相当长时间,密歇根在文化上和早期新英格兰文化很相近……新英格兰扬基人口的庞大数量使得密歇根在内战前时期边疆州当中与众不同。因为这种传统,密歇根站在1840年代和1850年代的废奴十字军和改革的前列。

Alhough I can’t find proof of this specifically, I know that Michigan was settled from the south up, and I suspect that these New England settlers concentrated in the southern regions and that the north was settled by a more diverse group of whites who lacked the New England connection.

虽然我不能发现专门的证据,我知道密歇根是从南方被开拓的,我怀疑新英格兰开拓者集中于南部区域,而北部则被更多元的白人群体开拓,这些人缺乏和新英格兰地区的联系。

Here’s something else cool. We can’t track Borderers directly because there’s no “Borderer” or “Scots-Irish” option on the US census. But Albion’s Seed points out that the Borderers were uniquely likely to identify as just “American” and deliberately forgot their past ancestry as fast as they could.

还有更有趣的发现。我们不能直接跟踪边民,因为在美国人口普查中没有“边民”或者“苏格兰人-爱尔兰人”的选项。但是《阿尔比安的种子》一书指出,边民特别倾向于自我认同为“美国人”,并故意尽快忘记自己过去的先祖。

Meanwhile, when the census asks an ethnicity question about where your ancestors came from, every year some people will stubbornly ignore the point of the question and put down “America” (no, this does not track the distribution of Native American population). Here’s a map of so-called “unhyphenated Americans”, taken from this site:

同时,当普查问及关于你先祖来自何处的族裔问题时,每年都有一些人顽固的忽略这一问题的目的,而填上“美国”(不,这并不能代表印第安人的分布)。下面是所谓的“纯粹的美国人”的地图,来自这个网站。

这是2012年总统大选在郡层面的投票模式的地图。蓝色区域在南方精确地分布在大量非裔美国人聚居的所谓“黑带”上。在中西部的蓝色基本上是大城市。除了这些,选民主党的人只有新英格兰人(支持度很高!)和宾州德拉威尔河谷地区。

In fact, you can easily see the distinction between the Delaware Valley settled by Quakers in the east, and the backcountry area settled by Borderers in the west. Even the book’s footnote about how a few Borderers settled in the mountains of New Hampshire is associated with a few spots of red in the mountains of New Hampshire ruining an otherwise near-perfect Democratic sweep of the north.

事实上,你能一眼看出,贵格会开拓的东部德拉威尔河谷和边民开拓的西部区域之间的区别。即便是书中脚注提到的少量边民移居新罕布尔州群山也能对应图中新罕布尔州群山中的几个红点,如果不是这几个红点,民主党在北方就拥有了完美的全胜。

One anomaly in this story is a kind of linear distribution of blue across southern Michigan, too big to be explained solely by the blacks of Detroit. But a quick look at Wikipedia’s History of Michigan finds:

这个故事中的一个异常就是在南密歇根存在一种线性分布的蓝色,面积太大,不能仅用底特律的黑人来解释。但是快速浏览维基百科上密歇根的历史条目就会发现:

In the 1820s and 1830s migrants from New England began moving to what is now Michigan in large numbers (though there was a trickle of New England settlers who arrived before this date). These were “Yankee” settlers, that is to say they were descended from the English Puritans who settled New England during the colonial era….Due to the prevalence of New Englanders and New England transplants from upstate New York, Michigan was very culturally contiguous with early New England culture for much of its early history…The amount with which the New England Yankee population predominated made Michigan unique among frontier states in the antebellum period. Due to this heritage Michigan was on the forefront of the antislavery crusade and reforms during the 1840s and 1850s.

在1820年代到1830年代,来自新英格兰的移民大量移居到今日的密歇根(虽然有少量新英格兰开拓者在之前就移居此地)。这些是“扬基”开拓者,这意味着他们是在殖民地时期住在新英格兰的英国清教徒的后裔……因为新英格兰人众多,以及从纽约上州移入的新英格兰人,在它早期历史的相当长时间,密歇根在文化上和早期新英格兰文化很相近……新英格兰扬基人口的庞大数量使得密歇根在内战前时期边疆州当中与众不同。因为这种传统,密歇根站在1840年代和1850年代的废奴十字军和改革的前列。

Alhough I can’t find proof of this specifically, I know that Michigan was settled from the south up, and I suspect that these New England settlers concentrated in the southern regions and that the north was settled by a more diverse group of whites who lacked the New England connection.

虽然我不能发现专门的证据,我知道密歇根是从南方被开拓的,我怀疑新英格兰开拓者集中于南部区域,而北部则被更多元的白人群体开拓,这些人缺乏和新英格兰地区的联系。

Here’s something else cool. We can’t track Borderers directly because there’s no “Borderer” or “Scots-Irish” option on the US census. But Albion’s Seed points out that the Borderers were uniquely likely to identify as just “American” and deliberately forgot their past ancestry as fast as they could.

还有更有趣的发现。我们不能直接跟踪边民,因为在美国人口普查中没有“边民”或者“苏格兰人-爱尔兰人”的选项。但是《阿尔比安的种子》一书指出,边民特别倾向于自我认同为“美国人”,并故意尽快忘记自己过去的先祖。

Meanwhile, when the census asks an ethnicity question about where your ancestors came from, every year some people will stubbornly ignore the point of the question and put down “America” (no, this does not track the distribution of Native American population). Here’s a map of so-called “unhyphenated Americans”, taken from this site:

同时,当普查问及关于你先祖来自何处的族裔问题时,每年都有一些人顽固的忽略这一问题的目的,而填上“美国”(不,这并不能代表印第安人的分布)。下面是所谓的“纯粹的美国人”的地图,来自这个网站。

We see a strong focus on the Appalachian Mountains, especially West Virginia, Tennesee, and Kentucky, bleeding into the rest of the South. Aside from west Pennsylvania, this is very close to where we would expect to find the Borderers. Could these be the same groups?

我们看到了该人群在阿巴拉契亚山脉区域有很高的密度,尤其是西弗吉尼亚,田纳西,和肯塔基,延伸到南方其他地区。除了西宾夕法尼亚之外,这和我们预期能发现边民的地区非常接近。这些可能是相同的人群吗?

Meanwhile, here is a map of where Obama underperformed the usual Democratic vote worst in 2008:

同时,这里还有奥巴马在08年民主党选举中表现最差的地区的一张地图:

We see a strong focus on the Appalachian Mountains, especially West Virginia, Tennesee, and Kentucky, bleeding into the rest of the South. Aside from west Pennsylvania, this is very close to where we would expect to find the Borderers. Could these be the same groups?

我们看到了该人群在阿巴拉契亚山脉区域有很高的密度,尤其是西弗吉尼亚,田纳西,和肯塔基,延伸到南方其他地区。除了西宾夕法尼亚之外,这和我们预期能发现边民的地区非常接近。这些可能是相同的人群吗?

Meanwhile, here is a map of where Obama underperformed the usual Democratic vote worst in 2008:

同时,这里还有奥巴马在08年民主党选举中表现最差的地区的一张地图:

These maps are small and lossy, and surely unhyphenatedness is not an exact proxy for Border ancestry – but they are nevertheless intriguing. You may also be interested in the Washington Post’s correlation between distribution of unhyphenated Americans and Trump voters, or the Atlantic’s article on Trump and Borderers.

这些地图也许小且模糊,而且纯种美国人认同也不是边民先祖的精确表征——但是它们仍然十分吸引人。你也许会对《华盛顿邮报》在纯种美国人分布和川普支持者之间相关性的报道感兴趣,还有《大西洋月刊》关于川普和边民的文章。

If I’m going to map these cultural affiliations to ancestry, do I have to walk back on my previous theory that they are related to class? Maybe I should. But I also think we can posit complicated interactions between these ideas. Consider for example the interaction between race and class; a black person with a white-sounding name, who speaks with a white-sounding accent, and who adopts white culture (eg listens to classical music, wears business suits) is far more likely to seem upper-class than a black person with a black-sounding name, a black accent, and black cultural preferences; a white person who seems black in some way (listens to hip-hop, wears baggy clothes) is more likely to seem lower-class. This doesn’t mean race and class are exactly the same thing, but it does mean that some races get stereotyped as upper-class and others as lower-class, and that people’s racial identifiers may change based on where they are in the class structure.

如果我把这些文化偏好对应到祖先谱系,我是否也不得不回到我之前的理论上,即这些和阶层有关?也许我应该这么做。但是我也认为我们应该注意这些看法之间的交互作用。比如考虑一下种族和阶层的交互关系;一个黑人带着一个白人式的名字,带白人口音,适应了白人文化(比如听古典音乐,穿西装),则比取黑人名、带黑人口音、偏好黑人文化的黑人更可能是上等阶级;一个某方面像黑人的白人(听嘻哈,穿松垮的衣服)则更可能属于底层。这并不是说种族和阶层完全是一码事,但是这说明一些族群给人的固定印象是上层,另一些是底层,而基于人们在阶层结构中位置,人们的和种族相关的特征可能会变化。

I think something similar is probably going on with these forms of ancestry. The education system is probably dominated by descendents of New Englanders and Pennsylvanians; they had an opportunity to influence the culture of academia and the educated classes more generally, they took it, and now anybody of any background who makes it into that world is going to be socialized according to their rules. Likewise, people in poorer and more rural environments will be surrounded by people of Borderer ancestry and acculturated by Borderer cultural products and end up a little more like that group. As a result, ethnic markers have turned into and merged with class markers in complicated ways.

我认为族裔血统的构成中,很可能发生了相似的事情。教育系统很可能被新英格兰人和宾夕法尼亚人把持,他们更有机会普遍地影响学术界的文化和受教育阶层,他们把握了这个机会,现在任何背景的人,要进入他们的世界,都会按照他们的规则被社会化。相似的,更穷和更乡村化的人,被边民的先祖和边民文化的产物包围,最终变得有点像这个群体。结果,族裔标志以种种复杂的方式转化成了阶层标志并与之融合。

Indeed, some kind of acculturation process has to have been going on, since most of the people in these areas today are not the descendents of the original settlers. But such a process seems very likely. Just to take an example, most of the Jews I know (including my own family) came into the country via New York, live somewhere on the coast, and have very Blue Tribe values. But Southern Jews believed in the Confederacy as strongly as any Virginian – see for example Judah Benjamin. And Barry Goldwater, a half-Jew raised in Arizona, invented the modern version of conservativism that seems closest to some Borderer beliefs.

的确,某种同化过程一定发生过,因为这些地区今天的大部分人并不是初代开拓者的后代。但是这样一个过程很可能发生。仅举一个例子,大部分我所认识的犹太人(包括我自己的家庭),从纽约来到这个国家,生活在靠海岸的某处,拥有蓝色的价值观。但是南方犹太人曾和任何弗吉尼亚人一样,相信南部邦联——可以参考Judah Benjamin的例子。而且Barry Goldwater,一个长在亚利桑那的半血犹太人,发明了现代版本的保守主义,其观点看起来最接近一些边民信仰。

All of this is very speculative, with some obvious flaws. What do we make of other countries like Britain or Germany with superficially similar splits but very different histories? Why should Puritans lose their religion and sexual prudery, but keep their interest in moralistic reform? There are whole heaps of questions like these.

所有这些都是很大胆的假设,带有一些明显的缺陷。对于英国或者德国,这些国家表面上有类似的分裂,但是有很不同的历史,我们如何来解释呢?为什么清教徒失去了他们的宗教和在性上的规矩,但是仍然在道德改革上保持兴趣?还有一大堆类似的问题。

But look. Before I had any idea about any of this, I wrote that American society seems divided into two strata, one of which is marked by emphasis on education, interest in moral reforms, racial tolerance, low teenage pregnancy, academic/financial jobs, and Democratic party affiliation, and furthermore that this group was centered in the North.

但是看看,在我有这些想法之前,我就曾写道美国社会看来被分裂成两层,其中之一有以下特征:重视教育、道德变革、种族宽容,很低的未成年怀孕率,学术和财经工作,以及支持民主党,而且这个群体以北方为中心。

Meanwhile, now I learn that the North was settled by two groups that when combined have emphasis on education, interest in moral reforms, racial tolerance, low teenage pregnancy, an academic and mercantile history, and were the heartland of the historical Whigs and Republicans who preceded the modern Democratic Party.

同时,我现在知道了北方曾被两个团体所开拓,两个群体结合起来,拥有以下特征:重视教育、道德变革、种族宽容,很低的未成年怀孕率 ,具有学术和商业历史,而且是历史上辉格党和共和党(后来的地位被现代的民主党取代)的核心地域。

And I wrote about another stratum centered in the South marked by poor education, gun culture, culture of violence, xenophobia, high teenage pregnancy, militarism, patriotism, country western music, and support for the Republican Party. And now I learn that the South was settled by a group noted even in the 1700s for its poor education, gun culture, culture of violence, xenophobia, high premarital pregnancy, militarism, patriotism, accent exactly like the modern country western accent, and support for the Democratic-Republicans who preceded the modern Republican Party.

我还写到过另一个集中于南方的阶层,它以教育贫乏,枪文化,暴力文化,排外,高未成年人怀孕率,军国主义,爱国主义,西部乡村音乐,和支持共和党为特征。现在我知道,开拓南方的群体,在18世纪就以教育的贫乏, 枪文化,暴力文化,排外,高未成年人怀孕率,尚武精神,爱国主义,接近现代西部乡村的口音,以及支持民主-共和党为特征(后来地位被现代的共和党取代)。

If this is true, I think it paints a very pessimistic world-view. The “iceberg model” of culture argues that apart from the surface cultural features we all recognize like language, clothing, and food, there are deeper levels of culture that determine the features and institutions of a people: whether they are progressive or traditional, peaceful or warlike, mercantile or self-contained.

如果这是真的,我认为这给出了一个非常悲观的世界图景。文化的“冰山模型”认为,撇开我们都能识别的文化表面特征,例如语言、衣着、和食物,存在更深层次的文化,它们决定了上述特征和人们的制度:决定他们是进步的还是传统的,和平的还是好战的,爱经商的还是自给自足的。

We grudgingly acknowledge these features when we admit that maybe making the Middle East exactly like America in every way is more of a long-term project than something that will happen as soon as we kick out the latest dictator and get treated as liberators. Part of us may still want to believe that pure reason is the universal solvent, that those Afghans will come around once they realize that being a secular liberal democracy is obviously great.

当我们承认也许让中东在每一方面都变成和美国一样是一个长期过程,而不是如我们把最近的独裁者赶下台,像解放者般被接待那么快,我们就是在勉强承认这些文化特征的存在。我们中的部分人还想相信纯粹理性是普遍适用的答案,只要阿富汗人意识到一个世俗化的自由主义的民主制度明显很棒,他们就会觉醒。

But we keep having deep culture shoved in our face again and again, and we don’t know how to get rid of it. This has led to reasonable speculation that some aspects of it might even be genetic – something which would explain a lot, though not its ability to acculturate recent arrivals.

但是我们已经一而再地被深层文化打脸,我们不知道如何摆脱它。这导致了合理的猜想,深层文化的某方面可能是遗传性的——这可以解释很多事情,虽然这个因素不能解释其同化最近的新来者的能力。

This is a hard pill to swallow even when we’re talking about Afghanistan. But it becomes doubly unpleasant when we think about it in the sense of our neighbors and fellow citizens in a modern democracy. What, after all, is the point? A democracy made up of 49% extremely liberal Americans and 51% fundamentalist Taliban Afghans would be something very different from the democratic ideal; even if occasionally a super-charismatic American candidate could win over enough marginal Afghans to take power, there’s none of the give-and-take, none of the competition within the marketplace of ideas, that makes democracy so attractive. Just two groups competing to dominate one another, with the fact that the competition is peaceful being at best a consolation prize.

即便我们讨论的是阿富汗,这也是一枚难以下咽的药丸。但如果我们从现代民主制中我们的邻舍和公民同胞的角度来考虑这个问题时,难受程度又要翻倍。这到底有什么意义?一个由49%的极端自由派的美国人和51%的基本教义派的阿富汗塔利班组成的民主制恐怕和民主典范非常不同;即使有时,一个很有人格魅力的美国候选人能赢得足够的阿富汗人摇摆票,获得权力,这里也没有讨价还价,没有思想市场的竞争,而正是这些因素才使得民主制如此有吸引力。只剩两个团体相互竞争来统治对方,事实上,如果竞争是和平的,就已经是谢天谢地了。

If America is best explained as a Puritan-Quaker culture locked in a death-match with a Cavalier-Borderer culture, with all of the appeals to freedom and equality and order and justice being just so many epiphenomena – well, I’m not sure what to do with that information.

如果美国可以很好地被解释成一种清教徒-贵格会文化,和一种骑士党-边民文化锁在一起的拼死对决,并且所有对自由,平等,秩序,正义的呼求仅是众多附带现象——那么我不确定该如何处理这个信息。

Push it under the rug? Say “Well, my culture is better, so I intend to do as good a job dominating yours as possible?” Agree that We Are Very Different Yet In The End All The Same And So Must Seek Common Ground? Start researching genetic engineering? Maybe secede?

把它藏在桌布下?说“好,我的文化更好,所以我打算竭尽全力做做好事,来统治你?”同意我们是非常不同的,但最终我们会变得一样,所以我们必须寻求共同立场?开始研究基因工程?也许独立分裂?

I’m not a Trump fan much more than I’m an Osama bin Laden fan; if somehow Osama ended up being elected President, should I start thinking “Maybe that time we made a country that was 49% people like me and 51% members of the Taliban –maybe that was a bad idea“.

我不是个川普粉,就像我不是奥萨马·本·拉登粉丝一样;如果不知何故,本·拉登当选了总统,我应该开始思考“也许那时候我们由49%的像我这样的人和51%的塔利班组成了一个国家——也许这是一个坏主意”。

I don’t know. But I highly recommend Albion’s Seed as an entertaining and enlightening work of historical scholarship which will be absolutely delightful if you don’t fret too much over all of the existential questions it raises.

我不知道。但是我高度推荐《阿尔比安的种子》这本富有娱乐性和启发性的历史学著作。如果你没有过多地被它引起的实在性问题吓到,读它绝对会是非常愉悦的。

(编辑:辉格@whigzhou)

*注:本译文未经原作者授权,本站对原文不持有也不主张任何权利,如果你恰好对原文拥有权益并希望我们移除相关内容,请私信联系,我们会立即作出响应。

These maps are small and lossy, and surely unhyphenatedness is not an exact proxy for Border ancestry – but they are nevertheless intriguing. You may also be interested in the Washington Post’s correlation between distribution of unhyphenated Americans and Trump voters, or the Atlantic’s article on Trump and Borderers.

这些地图也许小且模糊,而且纯种美国人认同也不是边民先祖的精确表征——但是它们仍然十分吸引人。你也许会对《华盛顿邮报》在纯种美国人分布和川普支持者之间相关性的报道感兴趣,还有《大西洋月刊》关于川普和边民的文章。

If I’m going to map these cultural affiliations to ancestry, do I have to walk back on my previous theory that they are related to class? Maybe I should. But I also think we can posit complicated interactions between these ideas. Consider for example the interaction between race and class; a black person with a white-sounding name, who speaks with a white-sounding accent, and who adopts white culture (eg listens to classical music, wears business suits) is far more likely to seem upper-class than a black person with a black-sounding name, a black accent, and black cultural preferences; a white person who seems black in some way (listens to hip-hop, wears baggy clothes) is more likely to seem lower-class. This doesn’t mean race and class are exactly the same thing, but it does mean that some races get stereotyped as upper-class and others as lower-class, and that people’s racial identifiers may change based on where they are in the class structure.

如果我把这些文化偏好对应到祖先谱系,我是否也不得不回到我之前的理论上,即这些和阶层有关?也许我应该这么做。但是我也认为我们应该注意这些看法之间的交互作用。比如考虑一下种族和阶层的交互关系;一个黑人带着一个白人式的名字,带白人口音,适应了白人文化(比如听古典音乐,穿西装),则比取黑人名、带黑人口音、偏好黑人文化的黑人更可能是上等阶级;一个某方面像黑人的白人(听嘻哈,穿松垮的衣服)则更可能属于底层。这并不是说种族和阶层完全是一码事,但是这说明一些族群给人的固定印象是上层,另一些是底层,而基于人们在阶层结构中位置,人们的和种族相关的特征可能会变化。

I think something similar is probably going on with these forms of ancestry. The education system is probably dominated by descendents of New Englanders and Pennsylvanians; they had an opportunity to influence the culture of academia and the educated classes more generally, they took it, and now anybody of any background who makes it into that world is going to be socialized according to their rules. Likewise, people in poorer and more rural environments will be surrounded by people of Borderer ancestry and acculturated by Borderer cultural products and end up a little more like that group. As a result, ethnic markers have turned into and merged with class markers in complicated ways.

我认为族裔血统的构成中,很可能发生了相似的事情。教育系统很可能被新英格兰人和宾夕法尼亚人把持,他们更有机会普遍地影响学术界的文化和受教育阶层,他们把握了这个机会,现在任何背景的人,要进入他们的世界,都会按照他们的规则被社会化。相似的,更穷和更乡村化的人,被边民的先祖和边民文化的产物包围,最终变得有点像这个群体。结果,族裔标志以种种复杂的方式转化成了阶层标志并与之融合。

Indeed, some kind of acculturation process has to have been going on, since most of the people in these areas today are not the descendents of the original settlers. But such a process seems very likely. Just to take an example, most of the Jews I know (including my own family) came into the country via New York, live somewhere on the coast, and have very Blue Tribe values. But Southern Jews believed in the Confederacy as strongly as any Virginian – see for example Judah Benjamin. And Barry Goldwater, a half-Jew raised in Arizona, invented the modern version of conservativism that seems closest to some Borderer beliefs.

的确,某种同化过程一定发生过,因为这些地区今天的大部分人并不是初代开拓者的后代。但是这样一个过程很可能发生。仅举一个例子,大部分我所认识的犹太人(包括我自己的家庭),从纽约来到这个国家,生活在靠海岸的某处,拥有蓝色的价值观。但是南方犹太人曾和任何弗吉尼亚人一样,相信南部邦联——可以参考Judah Benjamin的例子。而且Barry Goldwater,一个长在亚利桑那的半血犹太人,发明了现代版本的保守主义,其观点看起来最接近一些边民信仰。

All of this is very speculative, with some obvious flaws. What do we make of other countries like Britain or Germany with superficially similar splits but very different histories? Why should Puritans lose their religion and sexual prudery, but keep their interest in moralistic reform? There are whole heaps of questions like these.

所有这些都是很大胆的假设,带有一些明显的缺陷。对于英国或者德国,这些国家表面上有类似的分裂,但是有很不同的历史,我们如何来解释呢?为什么清教徒失去了他们的宗教和在性上的规矩,但是仍然在道德改革上保持兴趣?还有一大堆类似的问题。

But look. Before I had any idea about any of this, I wrote that American society seems divided into two strata, one of which is marked by emphasis on education, interest in moral reforms, racial tolerance, low teenage pregnancy, academic/financial jobs, and Democratic party affiliation, and furthermore that this group was centered in the North.

但是看看,在我有这些想法之前,我就曾写道美国社会看来被分裂成两层,其中之一有以下特征:重视教育、道德变革、种族宽容,很低的未成年怀孕率,学术和财经工作,以及支持民主党,而且这个群体以北方为中心。

Meanwhile, now I learn that the North was settled by two groups that when combined have emphasis on education, interest in moral reforms, racial tolerance, low teenage pregnancy, an academic and mercantile history, and were the heartland of the historical Whigs and Republicans who preceded the modern Democratic Party.

同时,我现在知道了北方曾被两个团体所开拓,两个群体结合起来,拥有以下特征:重视教育、道德变革、种族宽容,很低的未成年怀孕率 ,具有学术和商业历史,而且是历史上辉格党和共和党(后来的地位被现代的民主党取代)的核心地域。

And I wrote about another stratum centered in the South marked by poor education, gun culture, culture of violence, xenophobia, high teenage pregnancy, militarism, patriotism, country western music, and support for the Republican Party. And now I learn that the South was settled by a group noted even in the 1700s for its poor education, gun culture, culture of violence, xenophobia, high premarital pregnancy, militarism, patriotism, accent exactly like the modern country western accent, and support for the Democratic-Republicans who preceded the modern Republican Party.

我还写到过另一个集中于南方的阶层,它以教育贫乏,枪文化,暴力文化,排外,高未成年人怀孕率,军国主义,爱国主义,西部乡村音乐,和支持共和党为特征。现在我知道,开拓南方的群体,在18世纪就以教育的贫乏, 枪文化,暴力文化,排外,高未成年人怀孕率,尚武精神,爱国主义,接近现代西部乡村的口音,以及支持民主-共和党为特征(后来地位被现代的共和党取代)。

If this is true, I think it paints a very pessimistic world-view. The “iceberg model” of culture argues that apart from the surface cultural features we all recognize like language, clothing, and food, there are deeper levels of culture that determine the features and institutions of a people: whether they are progressive or traditional, peaceful or warlike, mercantile or self-contained.

如果这是真的,我认为这给出了一个非常悲观的世界图景。文化的“冰山模型”认为,撇开我们都能识别的文化表面特征,例如语言、衣着、和食物,存在更深层次的文化,它们决定了上述特征和人们的制度:决定他们是进步的还是传统的,和平的还是好战的,爱经商的还是自给自足的。

We grudgingly acknowledge these features when we admit that maybe making the Middle East exactly like America in every way is more of a long-term project than something that will happen as soon as we kick out the latest dictator and get treated as liberators. Part of us may still want to believe that pure reason is the universal solvent, that those Afghans will come around once they realize that being a secular liberal democracy is obviously great.

当我们承认也许让中东在每一方面都变成和美国一样是一个长期过程,而不是如我们把最近的独裁者赶下台,像解放者般被接待那么快,我们就是在勉强承认这些文化特征的存在。我们中的部分人还想相信纯粹理性是普遍适用的答案,只要阿富汗人意识到一个世俗化的自由主义的民主制度明显很棒,他们就会觉醒。

But we keep having deep culture shoved in our face again and again, and we don’t know how to get rid of it. This has led to reasonable speculation that some aspects of it might even be genetic – something which would explain a lot, though not its ability to acculturate recent arrivals.

但是我们已经一而再地被深层文化打脸,我们不知道如何摆脱它。这导致了合理的猜想,深层文化的某方面可能是遗传性的——这可以解释很多事情,虽然这个因素不能解释其同化最近的新来者的能力。

This is a hard pill to swallow even when we’re talking about Afghanistan. But it becomes doubly unpleasant when we think about it in the sense of our neighbors and fellow citizens in a modern democracy. What, after all, is the point? A democracy made up of 49% extremely liberal Americans and 51% fundamentalist Taliban Afghans would be something very different from the democratic ideal; even if occasionally a super-charismatic American candidate could win over enough marginal Afghans to take power, there’s none of the give-and-take, none of the competition within the marketplace of ideas, that makes democracy so attractive. Just two groups competing to dominate one another, with the fact that the competition is peaceful being at best a consolation prize.

即便我们讨论的是阿富汗,这也是一枚难以下咽的药丸。但如果我们从现代民主制中我们的邻舍和公民同胞的角度来考虑这个问题时,难受程度又要翻倍。这到底有什么意义?一个由49%的极端自由派的美国人和51%的基本教义派的阿富汗塔利班组成的民主制恐怕和民主典范非常不同;即使有时,一个很有人格魅力的美国候选人能赢得足够的阿富汗人摇摆票,获得权力,这里也没有讨价还价,没有思想市场的竞争,而正是这些因素才使得民主制如此有吸引力。只剩两个团体相互竞争来统治对方,事实上,如果竞争是和平的,就已经是谢天谢地了。

If America is best explained as a Puritan-Quaker culture locked in a death-match with a Cavalier-Borderer culture, with all of the appeals to freedom and equality and order and justice being just so many epiphenomena – well, I’m not sure what to do with that information.

如果美国可以很好地被解释成一种清教徒-贵格会文化,和一种骑士党-边民文化锁在一起的拼死对决,并且所有对自由,平等,秩序,正义的呼求仅是众多附带现象——那么我不确定该如何处理这个信息。

Push it under the rug? Say “Well, my culture is better, so I intend to do as good a job dominating yours as possible?” Agree that We Are Very Different Yet In The End All The Same And So Must Seek Common Ground? Start researching genetic engineering? Maybe secede?

把它藏在桌布下?说“好,我的文化更好,所以我打算竭尽全力做做好事,来统治你?”同意我们是非常不同的,但最终我们会变得一样,所以我们必须寻求共同立场?开始研究基因工程?也许独立分裂?

I’m not a Trump fan much more than I’m an Osama bin Laden fan; if somehow Osama ended up being elected President, should I start thinking “Maybe that time we made a country that was 49% people like me and 51% members of the Taliban –maybe that was a bad idea“.

我不是个川普粉,就像我不是奥萨马·本·拉登粉丝一样;如果不知何故,本·拉登当选了总统,我应该开始思考“也许那时候我们由49%的像我这样的人和51%的塔利班组成了一个国家——也许这是一个坏主意”。

I don’t know. But I highly recommend Albion’s Seed as an entertaining and enlightening work of historical scholarship which will be absolutely delightful if you don’t fret too much over all of the existential questions it raises.

我不知道。但是我高度推荐《阿尔比安的种子》这本富有娱乐性和启发性的历史学著作。如果你没有过多地被它引起的实在性问题吓到,读它绝对会是非常愉悦的。

(编辑:辉格@whigzhou)

*注:本译文未经原作者授权,本站对原文不持有也不主张任何权利,如果你恰好对原文拥有权益并希望我们移除相关内容,请私信联系,我们会立即作出响应。

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

HOW CULTURE DROVE HUMAN EVOLUTION

A Conversation with Joseph Henrich

文化如何推动人类进化:与Joseph Henrich对话

时间:@ 2012-09-04

译者:沈沉(@你在何地-sxy)

校对:慕白(@李凤阳他说)

来源:https://www.edge.org/conversation/joseph_henrich-how-culture-drove-human-evolution

Part of my program of research is to convince people that they should stop distinguishing cultural and biological evolution as separate in that way. We want to think of it all as biological evolution.

导言:我的研究课题之一就是要让人们相信,我们应该停止以常见的方式在文化进化和生物进化之间做出截然区分。我们应该将整件事情当作生物进化过程来看待。

JOSEPH HENRICH is an anthropologist and Professor of Psychology and Economics. He is the Canada Research Chair in Culture, Cognition and Coevolution at University of British Columbia.

约瑟夫·亨里奇是一名人类学家,同时还担任心理学与经济学教授。他还是英属哥伦比亚大学(UBC)文化、认知和协同进化“加拿大首席研究员”。

[JOSEPH HENRICH:] The main questions I’ve been asking myself over the last couple years are broadly about how culture drove human evolution. Think back to when humans first got the capacity for cumulative cultural evolution—and by this I mean the ability for ideas to accumulate over generations, to get an increasingly complex tool starting from something simple. One generation adds a few things to it, the next generation adds a few more things, and the next generation, until it’s so complex that no one in the first generation could have invented it.

约瑟夫·亨里奇:过去几年,我反复追问自己的一个主要问题,大体上就是文化如何推动人类进化。我会回溯至人类刚刚获得累积性的文化进化能力的时候。我说的这种能力是指,观念在代际间不断积累,从很简单的东西发展出日益复杂的工具的能力。一代人添加一点点东西,下一代人又添加一点点东西,如此接力,直到最后得出的工具无比复杂,以至第一代人无论如何不可能发明出来。

This was a really important line in human evolution, and we’ve begun to pursue this idea called the cultural brain hypothesis—this is the idea that the real driver in the expansion of human brains was this growing cumulative body of cultural information, so that what our brains increasingly got good at was the ability to acquire information, store, process and retransmit this non genetic body of information.

这在人类进化中确实是非常重要的一条线索,我们现在已经开始探究一种叫做文化大脑假说的观点,这种观点认为,人脑增大的真正动力就是,文化信息以这种方式不断累积,由此导致我们的大脑越来越善于获取信息,存储、处理和传递这种非基因信息体。

~~~~~~~~

The two systems begin interacting over time, and the most important selection pressures over the course of human evolution are the t(more...)

~~~~~~~~

The two systems begin interacting over time, and the most important selection pressures over the course of human evolution are the things that culture creates—like tools. Compared to chimpanzees, we have high levels of manual dexterity. We're good at throwing objects. We can thread a needle. There are aspects of our brain that seem to be consistent with that as being an innate ability, but tools and artifacts (the kinds of things that one finds useful to throw or finds useful to manipulate) are themselves products of cultural evolution. 随着时间推移,两个系统开始相互作用。在人类进化的过程中,最重要的选择压力正是文化所生成的事物,比如工具。与黑猩猩相比,我们的手要灵巧得多,比如我们善于抛掷东西,我们能够穿针引线。我们大脑的某些方面与此高度协调,使得这种能力看上去似乎与生俱来,但工具和人工制品——那种我们觉得扔出去有用或操作起来有用的东西——本身则是文化进化的产物。 Another example here is fire and cooking. Richard Wrangham, for example, has argued that fire and cooking have been important selection pressures, but what often gets overlooked in understanding fire and cooking is that they're culturally transmitted—we're terrible at making fires actually. We have no innate fire-making ability. But once you got this idea for cooking and making fires to be culturally transmitted, then it created a whole new selection pressure that made our stomachs smaller, our teeth smaller, our gapes or holdings of our mouth smaller, it altered the length of our intestines. It had a whole bunch of downstream effects. 另外一个例子就是用火和烹饪。Richard Wrangham就提出,用火和烹饪一直都是非常重要的选择压力。但在看待用火和烹饪的问题上,经常容易忽略的一点是,它们实际是通过文化进行传递的——人类原本是不怎么会生火的。我们不具备生火的先天能力。但一旦烹饪和生火的观念通过文化得以传递,就创造出一种全新的选择压力,使我们的胃容量变小、牙齿变小、嘴能张开的幅度变小,一口能吃下的东西也变少,而且我们肠道的长度也发生改变。这就带来了一系列的下游效应。 Another area that we've worked on is social status. Early work on human status just took humans to have a kind of status that stems from non-human status. Chimps, other primates, have dominant status. The assumption for a long time was that status in humans was just a kind of human version of this dominant status, but if you apply this gene-culture co-evolutionary thinking, the idea that culture is one of the major selection pressures in human evolution, you come up with this idea that there might be a second kind of status. We call this status prestige. 我们研究的另一个领域是社会地位。有关人类社会地位的早期研究只是简单地假定,人类的地位有其非人类时期的根源。黑猩猩和其他灵长类社群中都有拥有宰制地位的个体。长期以来,人们假定,人类的地位属性只不过是动物群体中的宰制地位的人类版本。但如果运用这种“基因和文化协同进化”的观念,也就是说把文化作为人类进化中的一种主要选择压力,你就会意识到或许存在另外一种类型的地位。我们称其为“威望地位”。 This is the kind of status you get from being particularly knowledgeable or skilled in an area, and the reason it's a kind of status is because once animals, humans in this case, can learn from each other, they can possess resources. 当你在某个领域的知识特别丰富或技能特别熟练时,你就能得到这种地位。这之所以能成为一种地位,是因为一旦动物(此处就是人)能够彼此学习,它们自身便可拥有资源【编注:此句较绕口,意思是相互学习的可能性,使得个体所拥有的知识成为一种对他人也有价值的人力资源】。 You have information resources that can be tapped, and then you want to isolate the members of your group who are most likely to have a lot of this resources, meaning a lot of the knowledge or information that could be useful to you in the future. This causes you to focus on those individuals, differentially attend to them, preferentially listen to them and give them deference in exchange for knowledge that you get back, for copying opportunities in the future. 如果存在可资利用的信息资源,那你就会想把你所属团体之中最有可能拥有大量此类资源的人单独区分出来,这是一大堆你将来有可能用得上的知识或信息。这会促使你关注这些人,特别地留意他们,更乐于倾听他们的意见,敬重他们,以此作为从他们那里获得知识、在未来运用这些知识的回报。~~~~~~~~

From this we've argued that humans have two separate kinds of status, dominance and prestige, and these have quite different ethologies. Dominance [ethology] is about physical posture, of size (large expanded chest the way you'd see in apes). Subordinates in dominance hierarchies are afraid. They back away. They look away, where as prestige hierarchies are quite the opposite. 基于此,我们认为人类存在两种不同类型的地位,分别是宰制和威望,分别对应着不同的动物行为学。宰制(行为学)核心在于身体块头的展示(你能在猿类身上看到的那种大块胸肌)。在宰制等级中,处于从属地位的个体会感到害怕。他们会退缩。他们不会正视上级,而在威望等级中情况则正好相反。 You're attracted to prestigious individuals. You want to be near them. You want to look at them, watch them, listen to them, and interact with them. We've done a bunch of experimental work here at UBC and shown that that pattern is consistent, and it leads to more imitation. There may be even specific hormonal profiles with the two kinds of status. 你会被有威望的个体所吸引。你渴望亲近他们。你渴望看着他们,观察他们,倾听他们,与他们交往。在UBC(不列颠哥伦比亚大学),我们已经就此做过一连串实验,证明了这种模式总是存在,而且会引发更多的模仿。这两种不同的地位可能还对应着各自不同的激素配置。 I've also been trying to think broadly, and some of the big questions are, exactly when did this body of cumulative cultural evolution get started? Lately I've been pursuing the idea that it may have started early: at the origins of the genus, 1.8 million years ago when Homo habilis or Homo erectus first begins to emerge in Africa. 此外,我也一直在试图思考一些更为宏大的问题,比如,这一累积性的文化进化体到底是从什么时候开始的?最近,我一直致力于澄清一个想法,那就是它可能开始得很早:很可能在人属出现时就开始了,也就是180万年前能人或直立人最早出现于非洲的时候。 Typically, people thinking about human evolution have approached this as a two-part puzzle, as if there was a long period of genetic evolution until either 10,000 years ago or 40,000 years ago, depending on who you're reading, and then only after that did culture matter, and often little or no consideration given to a long period of interaction between genes and culture. 通常,研究人类进化的人在处理这一问题时,会把它看作是一个“两部分谜题”,就好像从一开始直到距今1万或4万年以前(具体时间取决于你正在阅读谁的研究),曾经存在过一个长时段的基因进化,自此以后,文化才开始发挥作用。他们很少或根本不会考虑基因和文化之间曾长期相互作用这种情形。 Of course, the evidence available in the Paleolithic record is pretty sparse, so another possibility is that it emerged about 800,000 years ago. One theoretical reason to think that that might be an important time to emerge is that there's theoretical models that show that culture, our ability to learn from others, is an adaptation to fluctuating environments. If you look at the paleo-climatic record, you can see that the environment starts to fluctuate a lot starting about 900,000 years ago and going to about six or five hundred thousand years ago. 当然,我们能得到的旧石器时代证据相当少。因此,另一种可能性是,这一文化进化体开始于大约80万年前。这个时间点之所以成为一个重要的起源时间选项,一个理论依据在于,已经有理论模型表明,文化——即我们从他人身上学习的能力——是我们对持续的环境变动的一种适应。翻一翻古气候记录就会发现,环境大概在距今90万年前的时候开始剧烈变动,直到距今60或50万年前才消停。 This would have created a selection pressure for lots of cultural learning for lots of focusing on other members of your group, and taking advantage of that cumulative body of non-genetic knowledge. 这有可能创造出一种选择压力,催生了更多的文化学习,促使人更多关注团体中的其他成员,也促使人们更多地利用那种累积性的非基因的知识体。~~~~~~~~

Another signature of cultural learning is regional differentiation and material culture, and you see that by about 400,000 years ago. So, you could have a kind of late emergence at 400,000 years ago. A middle guess would be 800,000 years ago based on the climate, and then the early guess would be, say, the origin of genus, 1.8 million years ago. 文化学习的另外一个鲜明特征是地区分化和物质文化,这一点在大约40万年前可以看到。所以还有一种说法,认为这一文化进化体始于40万年前。这一时间比较晚,持中的猜测则是基于气候的80万年前起源说,更早的猜测则是人属出现的时候,即180万年前。 Along these same lines, I've been trying to figure out what the ancestral ape would have looked like. We know that humans share a common ancestry with chimpanzees about five or six million years ago with chimpanzees and bonobos, and the question is, what kind of ape was that? 沿着同样的思考线索,我还一直试图弄清祖猿长成什么样子。我们知道,大概500万或600万年前,人类和黑猩猩、倭黑猩猩拥有共同的祖先,问题是,这是种什么样的猿? One possibility, and the typical assumption, is that the ape was more like a chimpanzee or a bonobo. But there's another possibility that it was a different kind of ape that we don't have in the modern world: a communal breeding ape that lives in family units rather than the kind of fission fusion you might see in chimpanzees, and that actually chimpanzees and bonobos took a separate turn, and that lineage eventually went to humans spurred off a whole bunch of different kinds of apes. In the Pliocene, we see lots of different kinds of apes in terms of different species of Australopithecus. 其中一种可能是,这种祖猿更像黑猩猩或倭黑猩猩,这也是通常的假设。但还有另外一种可能性,它们可能是一种当今世界已经不存在的完全不同的猿:一种以家庭为单位、合作繁殖的猿,而不是黑猩猩那种裂变融合群体【译注:指群体的规模和成员不断变动】,而且黑猩猩和倭黑猩猩实际上是往另外一个不同方向上演变了,而最终进化出人类的那一谱系则进化成为一系列不同种类的猿。在上新世,我们可以看到大量不同种类的猿,他们都是南猿的不同种。 I'm just beginning to get into that, and I haven't gotten very far, but I do have this strong sense that we now have evidence to suggest that humans were communal breeders, so that we lived in family groups maybe somewhat similar to the way gorillas live in family groups, and that this is a much better environment for the evolution of capacities for culture than typical in the chimpanzee model, because for cultural learning to really take off, you need more than one model. 我才刚刚开始研究这一问题,成果还不多,但我强烈地感觉到,我们现在已经有证据说人类曾是合作繁殖的,因此我们是生活于家庭群体之中的,某种程度上就像大猩猩现在的那种家庭群体生活一样。相比黑猩猩的那种模式,这一模式为文化能力进化提供的环境要好得多,因为文化学习要真正实现飞跃,必须得有多种模式。 You want a number of individuals in your social environment to be trying out different techniques—say different techniques for getting nuts or for finding food or for tracking animals. Then you need to pay attention to them so you can take advantage of the variation between them. If there's one member of your group who's doing it a little bit better, you preferentially learn from them, and then the next generation gets the best technique from the previous generation. 这需要你所在的社会环境中拥有许多个体去尝试各不相同的技术,比如说取出果仁或找到食物或追踪猎物的不同技术。然后你就需要细心关注他们,以便能充分利用他们彼此之间的差异变化。如果群体之中有一个成员比其他成员做得稍微好一点点,你就更乐于向他们学习,于是下一代就能从上一代学到最好的技术。 Other things I've been thinking about along these lines are just trying to think through all the different adaptations that would have resulted from this gene culture interaction. One thing that's been noted by a number of people is that humans are strangely good at long distance running. We seem to have long distance running adaptations. 沿着这条线索,我还在考虑其他一些问题,那就是基于这种基因与文化的相互作用,到底我们会出现哪些不同的适应性变化。其中许多人已经注意到的一点是,人类特别善于长距离奔跑,这一点相当令人诧异。我们身上似乎出现了长距离奔跑的适应性变化。 Our feet have a particular anatomy. We have sweat glands and we can run really far. Hunter-gatherers can chase down game by just running the antelope down until it collapses. We run marathons. We seem generally attracted to running, and the question is, how did we become such long distance runners? 我们的脚具有一种独特的生理构造。我们拥有汗腺,可以跑得很远。狩猎采集者要追捕羚羊的话,只需要追着它跑,直到猎物筋疲力尽自己倒下。我们能跑马拉松。我们似乎全都对跑步感兴趣。问题是,我们是如何变得这样善于长跑的呢? We don't see this in other kinds of animals. We think if it was an obvious adaptation, we'd see it recurring through nature, but only humans have it. The secret is that humans who don't know how to track animals, can't run them down, so you need to have a large body of tracking knowledge that allows you to interpret spoors and identify individual animals and track animals over long distances when you can't see the animal, and without that body of knowledge, we're not very good at running game down. 在其他动物身上,我们看不到这一点。我们认为,如果这是一种简单的适应,那我们就应该能在自然界中看到它重复出现,但这一现象只有人类身上有。这里的隐秘在于,如果有的人类不知道如何追踪猎物,那他就不可能尾随追捕,所以你需要拥有一大套的追踪知识,以便你能在看不到猎物的时候分析足迹,能正确辨识猎物个体并能长距离追踪到它。如果没有这一知识体系,我们是不善于把猎物追倒的。 There's an interaction between genes and culture. First you have to get the culturally transmitted knowledge about animal behavior and tracking and spoor knowledge and the ability to identify individuals, which is something you need to practice, and only after that can you begin to take advantage of long distance running techniques and being able to run animals down. 在基因与文化之间存在着相互作用。首先你需要拥有那套关于动物行为和追踪的知识、足迹知识和辨识猎物个体的能力,而这是通过文化传递的,是一种需要练习的东西,只有这样,你才能用上长跑技巧,才能把猎物追倒。 That's a potential source for figuring out the origins of capacities for culture, because to the degree that we have information about the anatomy of feet, we can use that to figure out when it started. The same idea follows from cooking and fire. Since we know that those are culturally transmitted now, when we begin to see evidence that that affected our anatomy, that gives us clues to the origins of our capacities for culture. 要弄清人类文化能力的起源,这是一个可以思考的方向,因为凭借对人类足部构造的了解,我们可以弄清文化进化开始的时间。同样的思路也可以用在烹饪和用火问题上。因为我们现已知道烹饪和用火都是通过文化传递的,因此,如果我们能够找到它们影响身体构造的证据,就有了探究我们的文化能力之起源的线索。~~~~~~~~

Most recently I've been also thinking about the evolution of societal complexity. This is the emergence of complex societies that happens after the origins of agriculture, when societies begin to get big and complex and you have lots of interactions among strangers, large-scale cooperation, market exchange, militaries, division of labor, substantial division of labor. We have a sense of the sequence of events, but we don't have good process descriptions of how it was. What are the causal processes that bring these things about? 最近,我还在思考社会复杂性的进化问题。这里说的是农业起源之后复杂社会的出现,社会开始变大、变复杂,在其中你能看到陌生人之间的大量互动、大范围的合作、市场交换、军队、劳动分工、深度劳动分工。我们对这些事件的发生次序有所了解,但对于它们到底是如何发生的,我们还没能形成一个很好的过程描叙。引发这些事件的因果过程到底是什么样的? One of the ideas I've been pursuing is that after the origins of agriculture, there was an intense period that continues today of intergroup competition, which favors groups who have social norms and institutions that can more effectively expand the group while maintaining internal harmony, leading to the benefits of exchange, of the ability to maintain markets, of division of labor and of higher levels of cooperation. Then you get intense competition amongst the early farming groups, and this is going to favor those groups who have the abilities to expand. 我一直在思考的一个想法是,在农业出现之后,曾有过一个群体之间激烈竞争的时期,一直持续到现在。这种竞争使得拥有社会规范和制度、从而能够更有效地在扩张的同时维持内部和谐的一类群体脱颖而出,进而凸显出了交易、维持市场的能力、劳动分工和更高水平的合作所能带来的好处。早期农耕群体之间存在激烈竞争,那些拥有扩张能力的群体在这种竞争中更占优势。 You need to be precise about what you mean by these cultural traits and norms. I've worked in a couple of different areas on this, and one is religion. We just got a big grant to study the cultural evolution of religion with the idea being that the religions of modern societies are quite different than the religions we see in hunter gatherers and small scale societies, because they've been shaped by this process over millennia, and specifically they've been shaped in ways that galvanize cooperation in larger groups and sustained cooperation amongst non relatives. 在谈及文化特征和规范时,需要精确界定它们表达的意思。我在许多不同领域中都研究过这一问题,其中一个领域就是宗教。我们刚刚拿到一大笔资金,来研究宗教的文化进化,主要的观点就是,现代社会的宗教与狩猎采集群体和小规模社会中的宗教大不相同,因为它们已经被这一进程不断塑造了几千年,特别是,它们已经被塑造得能够有助于大规模群体中的合作,以及非亲属之间的持续合作。 The emergence of high-moralizing gods is an important example of this. In small-scale hunter-gatherer religions, the gods are typically whimsical. They're amoral. They're not concerned with your sexual behavior or your social behavior. Often you'll make bargains with them, but as we begin to move to the religions in more complex societies, we find that the gods are increasingly moralizing. They're concerned about exactly the kinds of things that are going to be a problem for running a large-scale society, like how you treat other members of your religious group or your ethnic group. 这方面的一个重要例子就是具有高度道德教化意义的神的出现。在小规模狩猎采集群体的宗教中,神通常都是反复无常的。它们是非道德的。它们并不关心你的性行为或社会行为。通常你会跟它们讨价还价。但在更为复杂的社会中,我们发现神会变得越来越具有道德教化意义。它们所关注的,恰好就是会对大规模社会运行构成麻烦的那一类事情,比如你如何对待同一宗教团体或本种族中的其他成员。 Experiments run at UBC and elsewhere have shown that when you remind atheists, it doesn't matter, but if you remind believers of their god, believers cheat less, and they're more pro social or fair in exchange tasks, and the kinds of exchange tasks that they're more pro social in are the ones with anonymous others, or strangers. UBC和其他一些地方所做的实验都表明,如果你提醒无神论者注意自己的言行,基本没有什么效果,但如果你提醒有神论者,并抬出他们的神,他们就会更少说谎,在参与交易时也会表现得更亲社会或更公平,而且他们在其中表现得更亲社会的这类交易,其对象都是匿名人士或陌生人。 These are the kinds of things you need to make a market run to have a successful division of labor. We've been pursuing that hypothesis and, in fact, we've just sent a number of psychologists and anthropologists to the field, and we'll be doing more of that in the coming years to do these kinds of experiments in a diverse range of societies, seeing if the moralizing gods of a variety of religions create these same kinds of effects. 这恰好是维持市场运转、成功维系劳动分工所需要的特征。我们近来一直在研究这个假说,事实上,我们不久前刚派出了一批心理学家和人类学家就此去做田野研究,未来几年还会加大力度,在大量不同社会群体中去做这类实验,以检验不同宗教中的教化性神是否都能造成以上同样的效果。~~~~~~~~

We also think that ritual plays a role in this in that rituals seem to be sets of practices engineered by cultural evolution to be effective at transmitting belief and transmitting faith. By attending a ritual, you elevate the degree of belief in the high-moralizing gods or the priests of the religion by the ritual practice. If you break down rituals common in many religions, they put the words in the mouths of a prestigious member of the group, someone everyone respects. That makes it more likely to transmit and be believed. 我们还认为,仪式在文化进化中发挥了作用。仪式似乎是文化进化所创造出来的一整套行为,有助于信念和信仰的传递。通过参与仪式,你就能通过仪式行为提高对高度教化性的神或传教者的信仰程度。如果你分析一下在许多宗教中都能找到的仪式行为就会发现,它们会借群体中某个威望很高、大家都尊重的人物之口来宣之于众。这会令其更易传播、更可能被相信。 People also engage in what we call credibility-enhancing displays [during rituals]. These are costly things. It might be an animal sacrifice or the giving of a large sum of money or some kind of painful initiation rite like circumcision, which one would only engage in if one actually believed in it. It's a demonstration of true belief, which then makes the observers more likely to acquire the belief. (在仪式过程中,)人们也会参与我们称为“提升可信度”的行为。这是一种代价颇高的事情。可能是以动物献祭,或者捐出大笔钱财,或者是某种痛苦的加入仪式,比如割礼,这些事都是只有真正的信徒才会参与的,是真信仰的展示,并能增加旁观者接受这些信仰的可能性。 Speaking in unison, large congregations saying the same thing, this all taps our capacity for conformist transmission; the fact that we weight what everybody believes in deciding in what we believe. 齐声说话,大规模集会倾诉同样的内容,这些都是在利用人们实现从众传递的潜力——也就是说我们在选择自己要相信什么的时候会考虑其他人都相信些什么。 These seem to want to tap our cultural transmission abilities to deepen the faith, and one of the interesting kind of ways that this has developed is that high-moralizing gods will often require rituals of this kind, and then by forcing people to routinely do the rituals, they then guarantee that the next generation acquires a deepened faith in the god, and then the whole thing perpetuates itself. It creates a self-perpetuating cycle. 这就像是要利用文化传递能力来加深信仰,它发展出来的有趣方式之一是,高度教化性的神通常都要求执行这类仪式,通过强迫人们经常性地履行仪式,就能保证下一代人对神能够拥有更深一层的信仰,然后整套体系就能实现永续。它创造出了一个自我存续的循环。 We think religions are just one element, one way in which culture has figured out ways to expand the sphere of cooperation and allow markets to form and people to exchange and to maintain the substantial division of labor. 我们认为,文化已经发展出了许多方式来扩大合作领域、允许市场形成、促进人们之间的交易,并维持明确的劳动分工,而宗教只是其中之一。 One of the interesting things about the division of labor is that you're not going to specialize in a particular trade—maybe you make steel plows—unless you know that there are other people who are specializing in other kinds of trades which you need—say food or say materials for making housing, and you have to be confident that you can trade with them or exchange with them and get the other things you need. 关于劳动分工,有一点非常有趣:你要选择专门从事某一特定行业,比如打造铁犁具,这需要一个前提,那就是你得知道有人专门从事你对之有需求的其他一些行业,比如食品或建材,而且你需要确信,自己能与他们进行贸易或交换,能够得到你需要的其他东西。 There's a lot of risk in developing specialization because you have to be confident that there's a market there that you can engage with. Whereas if you're a generalist and you do a little bit of farming, a little bit of manufacturing, then you're much less reliant on the market. 发展专业分工有很大的风险,因为你必须确信存在一个你能够利用的市场。如果你是个多面手,能做一点农活,再从事一些制造,那么你对这个市场的依赖度就大幅降低。 Markets require a great deal of trust and a great deal of cooperation to work. Sometimes you get the impression from economics that markets are for self-interested individuals. They're actually the opposite. Self-interested individuals don't specialize, and they don't take it [to market], because there's all this trust and fairness that are required to make markets run with impersonal others. 市场的运转需要很高的信任和大量的合作。你会从经济学得知,市场是由自利的个体组成的。实际上正好相反。自利的个体没法专业化,不能形成市场,因为要使市场在素昧平生的陌路人之间运作,那需要非常高的信任和公平。~~~~~~~~

In developing this line of thought, one of the things you need to be clear about is what you mean by culture and culture evolution. Culture is one of those terms that has lots of different meanings, and people have used it lots of different ways. In the intellectual tradition that I'm building on, culture is information stored in people's heads that gets there by some kind of social learning—so imitation, teaching, any kind of observational learning. 沿着这条思路想问题时,你需要清晰界定的事物之一就是文化和文化进化的含义。文化是那种带有很多不同含义的词汇,人们已经在用不同方式使用它。在我所背靠的智识传统中,文化指的是人们通过某种形式的社会化学习——如模仿、教育或任何形式的观察学习——而获得并储存在自己头脑中的信息。 We tend to think of cultural transmission, or at least many people think of cultural transmission as relying on language, but that's in part because in our culture, especially among academics, there tends to be a lot of talking, but in lots of small-scale societies, it's quite clear that there is a ton of cultural transmission that is just strictly by observational learning. 我们,或至少很多人,都倾向于认为文化传递是依赖语言的,但造成这种理解的部分原因在于,在我们的文化里,特别是在学术界,人们倾向于进行大量的语言交流,但是在众多小型社群中,很明显大量的文化传递纯粹是依靠观察学习来实现的。 If you're trying to make a tool, you're mostly watching the physical movements of the hands and the strategies taken. You might get tips that are transmitted verbally as you go along. In building a house, you're looking at how the house is built together, again with verbal comments as supplements to getting a sense for how the house goes together. 如果你想学习制造工具,就得主要观察手部的物理运动,以及其中的技巧。在这个过程中你可能会获得一些口头传达的指点。如果要学建房子,你要观察房子到底是怎么建造起来的,当然也会得到一些口头评论,帮助你理解房子到底如何拼起来。 If you're copying how to shoot an arrow, you're watching body position and bow position and aiming, and you're not listening to a lot of exposition on it, although clearly the verbal part of the transmission helps. We think and there's experimental evidence that show you can transmit lots of stuff without using any words. 如果你是在学习射箭,你观察的是身体的姿势、弓箭的位置及如何瞄准,你不会去听一大堆阐释,虽然很明显这种传达的口头部分也是有帮助的。我们认为,而且也有很多实验证据表明,无需使用任何词语,也能传达很多信息。 This is information stored in people's brains, and when we look at other animals, we find that the evolutionary models of culture make really good predictions about culture in fish. Fish will learn food foraging preferences from each other, and non-human primates can learn from each other, but what we don't see amongst other animals is cumulative cultural evolution. The case in which the cultural transmission is high enough fidelity that you can learn one thing from one generation, and that begins to accumulate in subsequent generations. 这是储存在人脑中的信息,当我们观察其他动物的时候,我们发现文化的进化模型能够很好地预测鱼类的文化。鱼类能够相互学习觅食偏好,人类之外的灵长类也能相互学习,但我们在其他动物身上看不到累积性的文化进化。也就是那种能从一代人身上学会某样事物,然后在接下来的数代人中间开始逐步累积的足够准确的文化传递。 One possible exception to that is bird song. Bird songs accumulate in such that birds from large continents have more complex songs than birds from islands. It turns out humans from smaller islands have less complex material culture than humans from larger islands, at least until recently, until communication was opened up. One of the interesting lines of research that's come out of this recognition is the importance of population size and the interconnectedness for technology. 此处有一个可能的例外,那就是鸟鸣。鸟类的鸣叫方式能够累积,以至于大陆鸟类的鸣叫方式要比海岛鸟类的更复杂。我们还发现,直到不久之前,也就是直到交流开放之前,在物质文化的复杂程度方面,来自小型海岛的人群不如来自更大型海岛的人群。源于这一认知的有趣研究领域之一,就是人口规模和互联程度对科技的重要影响。~~~~~~~~

I began this investigation by looking at a case study in Tasmania. Tasmania's an island off the coast of Southern Victoria in Australia and the archeological record is really interesting in Tasmania. Up until about 10,000 years ago, 12,000 years ago, the archeology of Tasmania looks the same as Australia. It seems to be moving along together. It's getting a bit more complex over time, and then suddenly after 10,000 years ago, it takes a downturn. It becomes less complex. 调查开始之初,我回顾了一个关于塔斯马尼亚岛的案例研究。塔斯马尼亚岛是澳大利亚的维多利亚州南部海洋上的一个岛屿,这里的考古记录非常有趣。直到约1万年前,和1.2万年前,塔斯马尼亚岛的考古记录看起来都跟澳洲大陆是一样的。两者似乎是齐头并进的,随着时间推移而变得日渐复杂。但在距今1万年以后,突然它就衰退了,变得没有澳洲大陆复杂了。 The ability to make fire is probably lost. Bone tools are lost. Fishing is lost. Boats are probably lost. Meanwhile, things move along just fine back on the continent, so there's this kind of divergence, and one thing nice about this experiment is that there's good reason to believe that peoples were genetically the same. 生火的能力可能丢失了。骨制工具丢失了。不会打渔了。船可能也没有了。与此同时,大陆上的事物则照常发展,所以就出现了这种分化。这一案例特别好的一点在于,我们有很好的理由相信两地的人群原本拥有相同的基因。 You start out with two genetically well-intermixed peoples. Tasmania's actually connected to mainland Australia so it's just a peninsula. Then about 10,000 years ago, the environment changes, it gets warmer and the Bass Strait floods, so this cuts off Tasmania from the rest of Australia, and it's at that point that they begin to have this technological downturn. 最开始两个群体在基因方面是相互混杂的。塔斯马尼亚最早是跟澳大利亚本土连在一起的,因此只是个半岛。大约在距今1万年前,气候发生了变化,越来越暖,于是巴斯海峡形成了,把塔斯马尼亚岛和澳大利亚其余部分分隔开来。也就是在这时,他们开始出现这种技术上的倒退。 You can show that this is the kind of thing you'd expect if societies are like brains in the sense that they store information as a group and that when someone learns, they're learning from the most successful member, and that information is being passed from different communities, and the larger the population, the more different minds you have working on the problem. 假如把各个社会群体比作不同人的大脑,就可以说发生上述这种事情毫不奇怪。因为社会群体以集体的方式储存信息,如果某人要学习,他就会向最成功的成员学习,而且这种信息会在不同社群之间传播,人口规模越大,你在处理问题时所能依靠的不同头脑就更多。 If your number of minds working on the problem gets small enough, you can actually begin to lose information. There's a steady state level of information that depends on the size of your population and the interconnectedness. It also depends on the innovativeness of your individuals, but that has a relatively small effect compared to the effect of being well interconnected and having a large population. 如果处理问题时能够依靠的头脑数目少到一定程度,你实际上会开始丢失信息。信息的稳态水平依赖于人口规模和互联程度。它也依赖于个体的创造性,但后一方面的影响相对而言比较小,良好的互联水平和大量的人口更加重要。 There have been a number of tests of this recently, the best of which is this study by Rob Boyd and Michelle Kline in which they took the fishing technologies of different Oceanic islands from the time when Europeans first arrived, and they looked at how the population size of the island relates to the tool complexity, and larger islands had much bigger and more complex fishing technologies, and you can even show an effective contact. Some of the islands were in more or less contact with each other, and when you include that, you get the size effect, but you also get a contact effect, and the prediction is that if you're more in contact, you have fancier tools, and that seems to hold up. 在这方面,最近已经有了很多测试,其中最好的当属Rob Boyd和Michelle Kline所做的研究。他们研究了自欧洲人初次抵达以后大洋洲不同岛屿上的捕鱼技术,考察了岛上人口规模如何影响渔具的复杂度,结果发现更大的岛屿拥有更大型、更复杂的捕鱼技术。有效接触也会发挥作用。其中某些岛屿跟其他岛屿之间存在或多或少的接触,如果把这个考虑在内,就既能发现规模效应,又能发现接触效应,理论上的预测是,更多的接触就意味着更好的渔具,这似乎也得到了验证。 If you follow this idea a little bit further, then it does give you a sense that rates of innovation should continue to increase, especially with the emergence of communication technologies, because these allow ideas to flow very rapidly from place to place. 如果你顺着这一想法再进一小步,它就会促使你产生一种想法,那就是创新的速度应该还会继续提高,特别是在通信技术出现以后,因为这使得观念从一地到另一地的流动速度变得非常快。 An important thing to remember is that there's always an incentive to hide your information. As an individual inventor or company, you're best off if everybody else shares their ideas but you don't share your ideas because then you get to keep your good ideas, and nobody else gets exposed to them, and you get to use their good ideas, so you get to do more recombination. 这里要记住的重要一点是,对于你自己知道的信息,你总是有动力进行隐瞒。对于个体发明家或单个公司而言,如果其他所有人都分享他们的想法,而你不分享你的想法,那你就是最受益的。因为这种情况下你能保守自己的好想法,别人没法知道,而你却能使用他们的好想法,这样你就能尝试更多的组合。 Embedded in this whole information-sharing thing is a constant cooperative dilemma in which individuals have to be willing to share for the good of the group. They don't have to explicitly know it's for the good of the group, but the idea that a norm of information sharing is a really good norm to have because it helps everybody do better because we share more ideas, get more recombination of ideas. 信息分享本身就存在合作困境,这种情形是一致存在的。为了集体的利益,个体要有分享的意愿。他们不需要明确地知道这是为了集体的利益,但他们需要建立一个观念,即认为有一个信息分享的规范是件好事,因为这能帮助所有人过得更好,因为我们分享的观念越多,我们得到的观念组合就越多。~~~~~~~~

I've done a lot of work on marriage systems with the evolution of monogamy. We have a sort of human nature that pushes us towards polygyny whenever there are sufficient resources. Eighty-five percent of human societies have allowed men to have more than one wife, and very few societies have adopted polyandry which would be the flip side of this, and then there's actually a number of societies that allowed both, but they tended to be polygynous because, assuming you have enough resources, the men are going to be more interested in having more wives than the wives are interested in having more husbands, and the husbands aren't inclined to be second husbands as much as the women are willing to be second wives. 我在婚姻体制方面下了很多功夫,研究过一夫一妻制的进化。我们有某种天性,促使我们在资源充分的前提下追求一夫多妻。85%的人类社会曾允许男人拥有一个以上妻子,极少有社会采用过这一制度的对立面,即一妻多夫制。有些社会实际上两者都允许,但最终更可能出现一夫多妻,因为假定有充足的资源,男人会对拥有更多妻子更感兴趣,女人对于拥有更多丈夫就没那么感兴趣,而且丈夫们并不太愿意成为别人的二号丈夫,而女人在做别人的二号妻子方面意愿相对更强。 But in the modern world, of course, monogamy is normative, and people who have too many wives are thought poorly of by the larger society. The question is, how did this ever get in place? And of course, it traces back through Europe. 但是在现代社会,当然一夫一妻制是规范性的,而且那些拥有很多妻子的人会被更大社群当中的人瞧不起。问题是,到底怎么会变成这样的?当然,这要从欧洲往上追溯。 One of the things that distinguished Europe from the rest of the world was something called the European Marriage Pattern, and part of that was normative monogamy, the idea that taking a second wife was wrong as long as you still had the first wife, and this actually traces back to Rome and eventually to Athens. Athens legislates the first rules about monogamous marriage just before the Classical period. 欧洲区别于世界其他地方的一个要点就是欧洲婚姻模式,规范性一夫一妻制就是其中之一。认为只要你的第一个妻子还在,娶第二个妻子就是错误的,这种观念实际上可以追溯到古罗马,甚至古雅典。在古典时代开始之前,雅典人就正式奠定了一夫一妻制的最初规则。 This was an example of a case where people are ready to moralize it, and I like to view it as the evolution of this marriage system of monogamy. It's peculiar. It doesn't fit with what we know about human nature, but it does seem to have societal level benefits. It reduces male-male competition. 人们会把一些东西道德化,婚姻制度就是例证之一,而且我倾向于从一夫一妻制婚姻体制的进化这个角度来考虑。这是很特别的。它跟我们对人性的认知相左,但确实具有社会层面的好处。它能减少男性之间的竞争。 We think there's evidence to say it reduces crime, reduces substance abuse, and it also engages males in ways that cause them to discount the future less and engage in productive activities rather than taking a lot of risks which include crime and other things. Depending on what your value systems are, if you think freedom is really important, then you might be for polygyny, but if you want to trade freedom off against other social ills like high crime, then you might favor the laws that prohibit polygamy. 我们认为,有证据表明这一制度可以减少犯罪,减少毒品滥用,而且它还能吸引男性更多地重视未来,更多地参与生产性活动,而不是到处冒险,制造犯罪及其他事端。这取决于你的价值观体系,如果你认为自由非常重要,那么你可能会支持一夫多妻,但如果你愿意为了减少社会麻烦(如高犯罪率)而牺牲一些自由,那么你可能就会支持立法禁止多偶制。 When I talk about success and un-success, I don't mean anything moralizing. I'm talking about the cultural evolutionary processes that favor the spread of one idea over another. If I talk about normative monogamy as being successful, I mean that it spread, and in this case the idea is that it spread despite the fact that it's contrary to some aspects of human nature. It does harness our pair bonding in some aspects, so it's a complex story there, but it creates societal level benefits. 我所说的成功或不成功,并不具有任何道德意味。我要表达的只是,在文化进化的过程中,某个理念的传播压倒了另外一个理念。当我说规范性一夫一妻制成功了的时候,我的意思只是它传播开了,而且在这个例子中,尽管它与人性某些方面相抵触,但仍然得以传播开来。它确实在某些方面约束了我们的结成配偶的行为,所以这个故事很复杂,但它带来了社会层面的好处。 Societies that have this are better able to maintain a harmonious population, increase trade and exchange, and have economic growth more than societies that allow polygamy, especially if you have a society with widely varying amounts of wealth, especially among males. Then you're going to have a situation that would normally promote high levels of polygyny. 实行一夫一妻制的社会更能维持人与人之间的和谐,增加贸易和交易,实现更快的经济增长,而允许多偶制的社会在这些方面就要差一些,特别是如果这一社会里财富差异非常大时(尤其是在男性之间)。如果存在上述情形,通常都会加剧一夫多妻的程度。 The absolute levels of wealth difference of, say, between Bill Gates and Donald Trump and the billionaires of the world, and the men at the bottom end of the spectrum is much larger than it's ever been in human history, and that includes kings and emperors and things like that in terms of total control of absolute wealth. 比如说,一边是比尔·盖茨、唐纳德·特朗普以及世上的亿万富翁,另一边则是处于财富分配末端的众多人口,财富差异绝对水平远远超过人类历史上的任何时候,而且这还把历史上那些国王、帝王等人物都考虑了在内,他们可是绝对财富的全权控制者。 Males will be males in the sense that they'll try to obtain extra matings, but the billionaires are completely curbed in terms of what they would do if they could do what emperors have done throughout the ages. They have harems and stuff like that. Norms of modern society prevent that. 男性作为男性,就会力图拥有更多的配偶,但现在的亿万富翁在这一点上却受到了完全的约束;本来如果他们可以这么做,他们会这么做的,历史上的所有帝王都不例外。他们会形成后宫体制,或类似的体制,但现代社会的道德规范阻止了他们。 Otherwise, there would be massive male-male competition, and even to get into the mating and marriage market you would have to have a high level of wealth if we were to let nature take it's course as it did in the earliest empires. It depends on what your views are about freedom versus societal level benefits. 否则的话,如果我们像早期帝国那样,让天性不加阻碍地发展,那将会出现大规模的男性竞争,甚至是仅仅想进入配偶和婚姻市场,你就得拥有很多的财富。这取决于你如何看待自由和社会层面利益之间的取舍。~~~~~~~~