【2016-03-27】

@whigzhou: 在夏威夷被烟价惊了一下(如果是在纽约会更惊),于是想起数月前读到的一篇讨论香烟税的文章,至少在美国,香烟税是一种典型的穷人税,因为穷人抽烟更多,这回仔细一算才发觉这税对穷人有多重,一位纽约穷人若每天抽一包烟,每月就给政府交了300美元税,而实际上,纽约穷人烟民买烟要花掉1/4收入。

@whigzhou: 准确数字是23.6%,全美低收入烟民平均花14%收入买烟,对比万宝路在中国市场的零售价可知,其中(more...)

【2016-03-27】

@whigzhou: 在夏威夷被烟价惊了一下(如果是在纽约会更惊),于是想起数月前读到的一篇讨论香烟税的文章,至少在美国,香烟税是一种典型的穷人税,因为穷人抽烟更多,这回仔细一算才发觉这税对穷人有多重,一位纽约穷人若每天抽一包烟,每月就给政府交了300美元税,而实际上,纽约穷人烟民买烟要花掉1/4收入。

@whigzhou: 准确数字是23.6%,全美低收入烟民平均花14%收入买烟,对比万宝路在中国市场的零售价可知,其中(more...)

【2016-05-29】

@whigzhou: 依我的经验,当秋天气温从30度逐渐降至20度时,所穿的衣服从F30减至F20,当春天气温从10度逐渐升至20度时,所穿的衣服从S10增至S20,F20<S20,此为穿衣-气温函数之非对称性。

@whigzhou: 类似的,个人对某些商品的消费-价格函数也是非对称的,但方向相反,当初夏西瓜从5块1斤逐渐降至3块1斤时,你可能觉得,啊,好便宜,买一个,当秋天西瓜从1块1(more...)

【沐猿而冠·第7章·No31. 春运人潮的未来走向·后记】

根据皮尤中心2008年的一份报告[1],该年有12%的美国人更换了住所(这还是60多年来的最低值,40到60年代这个数字高达20%),截至当年,63%的成年人至少更换过一次居住城市(即只有37%从未在家乡以外居住过),其中43%在两个或更多州居住过,23%出生于美国的人认为现在所住的地方不是他“心目中的家乡(heart home)”。

中西部农业区流动性最低(54%更换过居住地),西部沿海最高(70(more...)

New Study Indicates Existence of Eight Conservative Social Psychologists

最近研究显示:保守派社会心理学家现存8位

作者:Jonathan Haidt @ 2016-1-7

译者:Marcel ZHANG(@马赫塞勒张)

校对:沈沉(@你在何地-sxy)

来源:Heterodox Academy,http://heterodoxacademy.org/2016/01/07/new-study-finds-conservative-social-psychologists/

Just how much viewpoint diversity do we have in social psychology? In 2011 nobody knew, so I asked 30 of my friends in the field to name a conservative. They came up with several names, but only one suspect admitted, under gentle interrogation, to being right of center.

社会心理学领域到底有多大的观点多样性?2011年时还没人知道,所以我询问了30个该领域的朋友,让他们举出一位保守派。结果他们提到了好几个名字,但在温和的盘问之下,只有一位嫌疑人承认了自己的政治倾向是中间偏右的。

A few months later I gave a talk at the annual convention of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology in which I pointed out the field’s political imbalance and why this was a threat to the quality of our research.

几个月后,我在人格与社会心理学协会(SPSP)年会上发言时,指出了该领域的政治失衡现象,以及为什么这种现象会对我们的研究质量造成威胁。

I asked the thousand-or-so people in the audience to declare their politics with a show of hands, and I estimated that roughly 80% self-identified as “liberal or left of center,” 2% (I counted exactly 20 hands) identified as “centrist or moderate,” 1% (12 hands) identified as libertarian, and, rounding to the nearest integer, zero percent (3 hands) identified as “conservative or right of center.” That gives us a left: right ratio of 266 to one. I didn’t think the real ratio was that high; I knew that some conservatives in the audience were probably afraid to raise their hands.

我要求在场的约一千名听众举手表明自己的政治倾向,估计大略有80%的人认为自己是“自由派或者中间偏左派”,有2%(我数下来不多不少20个人)认为自己是“中立派或者温和派”,只有1%(12个人)自认自由意志主义者,如果直接取整的话,几乎0%(3个人)自认“保守派或者中间偏右派”。我们看到的是一个266:1的左右派比值。我不认为真实的比值会如此之高,我知道当时听众席里有些保守派可能会怯于举手。

Some of my colleagues questioned the validity of such a simple and public method, but Yoel Inbar and Yoris Lammers conducted a more thorough and anonymous survey of the SPSP email list later that year, and they too found a very lopsided political ratio: 85% of the 291 respondents self-identified as liberal overall, and only 6% identified as conservative.

有些同事对我这种简易公开方式的有效性提出了质疑。但是,同年晚些时候,Yoel Inbar 和 Yoris Lammers在该协会邮件组中进行了一场更加彻底的匿名调查,结果他们也发现了一边倒的政见比值:总共291个调查对象中,有85%认为自己基本可以算作自由派,而只有6%的调查对象认为自己是保守派。

That gives us our first good estimate of the left-right ratio in social psychology: fourteen to one. It’s a much more valid method than my “show of hands” (which was(more...)

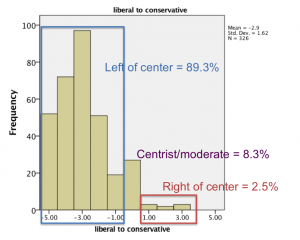

【图表一:政治倾向自评分】

The graph shows that 291 of the 326 people who responded to this question picked a left-of-center label (that’s 89.3%), and only 8 people (2.5%) picked a right of center label, giving us a Left to Right ratio of 36 to one. This is much higher than that found by Inbar and Lammers. The main source of political diversity appears to be the 27 people (including me) who self-identified as centrists. 图表显示,该题的326位回答者中有291位选择了中间偏左标签(占总数89.3%),而只有8位选择了中间偏右标签(占总数2.5%),这就得出了一个36:1的左右派比值。这比Inbar和Lammers发现的比值还高。政治多样性主要基于27位自我定义为中间派的回答者(包括本人在内)。 2)Presidential voting: 76 to one. 2)总统选举投票:76:1。 Another item asked: “Who did you vote for in the last presidential election (if you are not a US citizen, or if you did not vote, who would you have voted for if you had voted)? The options were: “Obama,” “Romney,” or “Other.” If we do a frequency plot of the 3 possible choices we get this: 另有一道题问到:“在上次总统大选中你把选票投给了谁(如果你不是美国公民,或者你并未投票的话,假设让你投票,你可能会投给谁)?”选项有这么几个:“奥巴马”、“罗姆尼”或“其他”。如果我们依照这三个选项绘制频率分布直方图,则得下图:

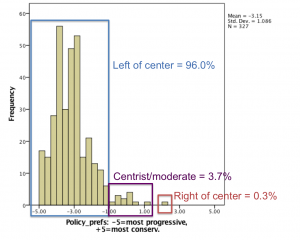

【图表二:2012年美国总统大选】

The graph shows that 305 of the 322 people (94.7%) who responded to this question voted for Obama, 4 (1.2%) voted for Romney, and 13 (4.0%) said they voted for another candidate. This gives us a Democrat to Republican ratio of 76 to one. 图表显示,该题的322位回答者中有305位(占94.7%)投给了奥巴马,4位(占1.2%)投给了罗姆尼,而有13位(占4.0%)回答者投给了其他总统候选人。这就得出了一个76:1的“驴象比”比值。 3)Views on political issues: 314 to one. 3)政治议题上的观点:314:1。 A third way of graphing the viewpoint diversity of these senior social psychologists is by computing an average score across all 9 of the politically valenced policy items. For each one, the 11 point response scale was labeled “strongly oppose” on the left-most point and “strongly support” on the right-most point. 将这些资深社会心理学家的观点多元状况图表化的第三条途径,就是算出他们在九道政治心理价问题上的平均得分。每个问题的答案选项都有11个,最左端的为“强烈反对”,最右端为“强烈支持”。 I converted all responses to the same 11 point scale used in figure 1 so that “strongly supporting” the progressive position (e.g., pro-choice) was scored as -5 and “strongly supporting” the conservative position (e.g., prayer in school) was scored as +5. That puts the leftists on the left and the rightists on the right of the graph. Here’s the graph: 我将所有回答都转换成与图表1中的11个选项一一对应,也就是说,“强烈支持”进步派立场的(比如主张堕胎权)就会被记作-5分,而“强烈支持”保守派立场(比如支持校内祷告)就会被记作5分。这样就可以在图表上把左派标到左侧,右派标到右侧。图表如下:

【图表三:对九个政治议题的观点】

I counted anyone whose average score fell between -1.0 and +1.0 (inclusive) as a centrist. The graph shows that 314 of the 327 participants (96.0%) had an average score below -1.0 (i.e., left of center), one had an average score above +1.0 (i.e., right of center), and 12 were centrists. That gives us a Left to Right ratio of 314 to one. 我将所有平均得分在-1.0与1.0之间的参与者都算作中间派。图表显示,在327名参与者中有314位(占96.0%)的平均得分低于-1.0(即中间偏左),只有一位参与者的平均得分高于1.0(即中间偏右),另外还有12位是中间派。这样我们就得出了一个314:1的左右派比值。 What does this mean? 这意味着什么? However you measure it, and for all samples measured so far, social psychology leans heavily to the left and has very few people right of center. Von Hippel and Buss’s new data confirms the story that a few of us told in a recent paper (Duarte, Crawford, Stern, Haidt, Jussim & Tetlock, 2015) in which we created the graph below, which shows just how fast psychology has been moving to the left since the 1990s. The ratio of Democrats to Republicans (diamonds) and liberals to conservatives (circles) was roughly 3 to 1 for most of the 20th century. But it skyrockets beginning in the 1990s as the Greatest Generation retires and the Baby Boomers take over. 不论你如何衡量,就目前已经测得的样本来看,社会心理学界已经左倾得非常严重了,只有很少人是中间偏右的。Von Hippel和Buss的新数据也证实了我们几个在最近的一篇论文(Duarte, Crawford, Stern, Haidt, Jussim和Tetlock于2015年发表)里说到的情况,文中我们绘制了下面这张图表,它显示了从1990年代起心理学界是以何等之快的速度左倾化的。“驴象比”(在图中以方块示出)和“左右比”(在图中以圆圈示出)比值在上个世纪基本为3:1。但随着“最伟大世代”【编注:作家Tom Brokaw将成长于大萧条年代,接着参加二战,随后又经历了战后大繁荣的那一代人称为最伟大一代】的退休和婴儿潮一代的接班,这个比值在90年代开始直线窜升。

【图表四: 1920年代起学院心理学家左右派比值的攀升。(详见Duarte等人在2015年发表的论文)】

Why does this matter? 这为什么重要? Most people know that professors in America, and in most countries, generally vote for left-leaning parties and policies. But few people realize just how fast things have changed since the 1990s. An academic field that leans left (or right) can still function, as long as ideological claims or politically motivated research is sure to be challenged. But when a field goes from leaning left to being entirely on the left, the normal safeguards of peer review and institutionalized disconfirmation break down. Research on politically controversial topics becomes unreliable because politically favored conclusions receive less-than-normal scrutiny while politically incorrect findings must scale mountains of motivated and hostile reasoning from reviewers and editors. 美国以及大多数国家的教授们一般都会支持左翼政党或政策,这没什么新鲜,但鲜为人知的是, 1990年代以来事态是以何其快的速度转变着。只要意识形态主张或者出于政治目的的研究仍必然会遭到挑战,那么一个左倾(或右倾)的学术领域就还能运转。但是当一个学术领域从左倾发展到铁板一块的左翼时,同行评议或者体制化否证的正常保障监督措施就会崩溃。对在政治上有争议的论题的研究会变得不再可靠,因为存在政治偏袒的结论现在受到的审查少之又少,而政治不正确的发现则需要排除万难,须要遭受评议人和编辑们发出的种种带有政治动机和敌意的论证。 I consider the rapid loss of political diversity, over the last 20 years, to be the second-greatest existential threat to the field of social psychology, after the “replication crisis.” The field is responding constructively to the replication crisis. Will it also attend to its political diversity crisis? Or will it continue to think of diversity only in terms of the demographic categories that most matter to people on the left: race, gender and sexual orientation? 我将过去二十年间发生的这次政见多样性的迅速退减视为,社会心理学领域的第二大致命威胁,仅次于“可重复性危机”。这个领域正在积极地应对可重复性危机,那么它也会去解决它的政见多样性危机吗?还是说,它仍旧只会从人口统计学这个对左派人士来说至关重要的角度来考虑多样性?只会考虑种族、性别和性向问题? I don’t mean to single out social psychology. It is the field that I know best, but what we have learned at Heterodox Academy is that this problem, this rapid shift to political purity, has happened to most fields in the humanities and social sciences in just the last 2 decades. 我并不是故意要把社会心理学挑出来。这只是我最熟悉的领域,但我们在异端学院意识到了:这个问题,即政治单一化现象,仅在过去的短短20年内就在大部分人文社科领域都已经发生了。 An optimistic ending 一个乐观的结局 I would like to end by thanking my colleagues. I have been raising a fuss about these issues since 2011. In that time I also moved from the left to the center, politically. I am no longer a progressive. So you might expect that I’ve been ostracized, but I have not. Nothing bad has happened to me. 我想以我对同事们的感激来结尾。从2011年开始我就因为这些事搞得他们鸡犬不宁,那时候我也在政治倾向方面由左派转变为中间派。我不再是个进步主义者了。所以你可能以为我已经被排挤了,但是并没有,万事顺遂。 Some of my colleagues believe that the political imbalance is not a problem. But the majority response has been, roughly: “This is really interesting. We really truly value diversity, and we agree with you and your co-authors that diversity of viewpoints is the kind that confers the most benefits on groups. But gosh, how are we going to get more?” 我的有些同事觉得政见失衡没什么大不了的。但大多数回答大概是这样的:“这确实挺有意思的。我们的确很看重多样性,而且我们同意你和你的合著者的观点,观点多样性是那种可以为团体带来最大益处的东西。但是啊,我们怎么才能获取更多多样性呢?” That’s our mission at Heterodox Academy – to figure out how to get more. It will be hard, but it can and must be done. Please see our “solutions page.” 这就是我们在异端学院中的使命了,那就是搞清楚如何能获得更多的多样性。道路是曲折的,但前途是光明的。请参看我们的“方案页”。 Post script: Paul Krugman recently referred to us at Heterodox Academy as “outraged conservatives,” and he said that the leftward shift in the academy was really just the rightward shift of the Republican Party since the 1990s. He suggests that professors didn’t change their views on policy, they just stopped identifying as Republicans as the party went off the deep end. 附:Paul Krugman最近将我们这些异端学院上的人称为“愤怒的保守派”,他说1990年代以来学界的左转其实只是共和党的右转。他的言下之意是,教授们并没有改变过他们的政见,他们只是在共和党转入极端时不再自我标榜为共和派了而已。 There is surely some truth to Krugman’s argument, but that doesn’t negate our claim that the makeup of the professoriate really did change after the Greatest Generation retired. Krugman’s argument could not explain graph #3, for example, which shows just a single person with views on social issues that are right of center. Also, I should point out that most of us at Heterodox Academy are not conservatives, and if you read everything on our site, it will be hard to find evidence of “outrage.” Krugman的质疑确实反映了部分事实,但这并没有驳倒我们的主张,最伟大世代逝去之后教授阶层的组成结构确实发生了变化。比如,Krugman的质疑就没能解释图表三里只有一个人对偏右社会事件支持的现象。此外,我必须要指出,异端学院上的大多数人都不是保守派,而且如果读过我们网站上的所有文章的话,你会很难发现有“愤怒”的踪迹。 (编辑:辉格@whigzhou) *注:本译文未经原作者授权,本站对原文不持有也不主张任何权利,如果你恰好对原文拥有权益并希望我们移除相关内容,请私信联系,我们会立即作出响应。——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

The Lower Productivity Of Organic Farming: A New Analysis And Its Big Implications

有机农业生产率更低:一项新的分析及其重大含义

作者:Steven Savage @ 2015-10-9

译者:沈沉(@你在何地-sxy)

校对:babyface_claire

来源:Forbes,http://www.forbes.com/sites/stevensavage/2015/10/09/the-organic-farming-yield-gap/

The productivity of organic farming is typically lower than that of comparable “conventional” farms. This difference is sometimes debated, but a recent USDA survey of organic agriculture demonstrates that commercial organic in the U.S. has a significant yield gap.

有机农业的生产率通常低于可比的“传统”农业。其中差异时有争论,不过美国农业部最近关于有机农业的一项调查证实,美国的商业有机作物存在一个巨大的产量差距。

I compared 2014 survey data from organic growers with overall agricultural yield statistics for that year on a crop by crop, state by state basis. The picture that emerges is clear – organic yields are mostly lower. To have raised all U.S. crops as organic in 2014 would have required farming of one hundred nine million more acres of land. That is an area equivalent to all the parkland and wildland areas in the lower 48 states or 1.8 times as much as all the urban land in the nation.

我将采自有机作物种植者的2014年调查数据与农业总产量统计数据分作物、分州别进行了对比,得出的画面非常清晰——有机作物的产量一般都更低。如果2014年全美农作物都是有机种植,那么需要耕种的土地将比实际多出1.09亿英亩。这一面积相当于本土48州所有绿地和荒地的总和,或全国所有城市用地之和的1.8倍。

As of 2014 the reported acreage of organic cropland only represented 0.44% of the total, but if organic were to expand significantly, its lower land-use-efficiency would become problematic. This is one of several reasons to question the assertion that organic farming is better for the environment.

到2014年,公开的有机农用地面积只占全部农地的0.44%,但如果有机种植大幅扩张,它那较低的用地效率将很棘手。有人断言有机农业对环境更有利,这里提到的只是质疑理由之一。

The USDA conducted a detailed survey of organics in 2008 and then again in 2014. Information is collected about the number of farms, the acres of crops harvested, the production from those acres, and the value of what is sold. The USDA also collects similar data every year for agriculture in general and makes it very accessible via Quick Stats.

美国农业部2008年对有机作物进行了一次详细调查,2014年又做了一次。采集的信息包括农场数量、作物收获面积、产量和卖出总价。美国农业部每年还针对全部农业采集类似数据,并在Quick Stats上公开发布。

It i(more...)

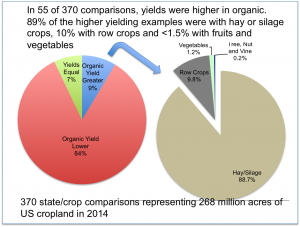

【2014年有机与传统农业统计数据比较概要】

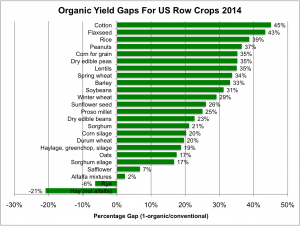

For 292 of those comparisons, the organic yields were lower (84% on an area basis). There were 55 comparisons where organic yield was higher, but 89% of the higher yielding organic examples involved hay and silage crops rather than food crops. The organic yield gap is predominant for row crops, fruit crops and vegetables as can be seen in the graphs below. 在其中292个比较结果中,有机作物产量都要更低(以面积而言占到84%)。有机作物产量更高的,有55组比较结果。但这些产量更高的案例中有89%种的是干草和青贮饲料作物,而非食用作物。以下图表显示:有机作物产量差距在中耕作物、水果作物和蔬菜中非常突出。 The reasons for the gap vary with crop and geography. In some cases the issue is the ability to meet periods of peak nutrient demand using only organic sources. The issue can be competition from weeds because herbicides are generally lacking for organic. In some cases its reflects higher yield loss to diseases and insects. Although organic farmers definitely use pesticides, the restriction to natural options can leave crops vulnerable to damage. 出现差距的原因随作物和地理不同而有所不同。在某些情形中,问题出在只用有机资源来满足营养需求高峰的能力上。问题也可能出在杂草竞争,因为有机作物中一般不用除草剂。在某些情形中,它反映的是因病害和虫害导致的减产。尽管种植有机作物的农场主绝对也会用杀虫剂,但是对天然产品的限制要求仍会让作物更易受到伤害。 I’ve posted a much more detailed summary of this information on SCRIBD with the data at the state level. 有关上述信息,我已在SCRIBD上贴了一份更加详细的摘要,用的是州级层面的数据。

【大量主要中耕作物采用有机种植时产量大幅降低】

【有机水果和坚果的产量绝大多数都大幅低于传统种植】

【蔬菜作物中的产量差距存在巨大差异】

There is some potential for artifacts within this data set. If the proportion of irrigated and non-irrigated land differs between organic and conventional that would skew the data. With lettuce and spinach it is likely that the organic is proportionally more in the “baby” category making yields appear dramatically lower. 这组数据中可能存在一些人为现象。如果在有机种植和传统种植中,灌溉地和非灌溉地的比例不同,那么数据就有所扭曲。生菜和菠菜的有机种植可能很大程度上仍属于“婴儿”类,故而产出差距看起来十分大。 But overall this window on farming is useful for understanding the current state of commercial organic production. Since the supply of prime farmland is finite, and water is in short supply in places like California, resource-use-efficiency is an issue even at the current scale of organic (1.5 million cropland acres, 3.6 million including pasture and rangeland). 但总体来说,这一农业信息窗口很有用,能让我们了解商业有机作物生产的现状。由于优质农田的供给是有限的,而在加州等地,水也存在供给短缺,因此,即便是以有机作物当前的种植面积(150万英亩耕地,包括草地和牧场则为360万亩)来说,资源利用效率也是个大问题。 You are welcome to comment here and/or to email me at [email protected]. I’d be happy to share a data file with interested parties and to get feedback about where particular yield comparisons might be misleading. A more detailed presentation is available at https://www.scribd.com/doc/283996769/The-Yield-Gap-For-Organic-Farming 欢迎提出评论或发送邮件至[email protected]。我愿意和感兴趣者分享数据文件,如果哪个具体的产量比较可能具有误导性,我也希望得到反馈。更详细的介绍请见:https://www.scribd.com/doc/283996769/The-Yield-Gap-For-Organic-Farming (编辑:辉格@whigzhou) *注:本译文未经原作者授权,本站对原文不持有也不主张任何权利,如果你恰好对原文拥有权益并希望我们移除相关内容,请私信联系,我们会立即作出响应。——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

【2016-05-24】

@whigzhou: 自由市场制度下,财产的初始分配根本不重要,整个宾夕法尼亚的土地起初全归小威廉·潘恩一人所有,这一事实对该州后来的社会结构有多大影响?彩票发明那么多年了,每年都有人中亿万大奖,你听说过哪个显贵家族是靠祖上中彩票发达的?

@whigzhou: 在《儿子照样升起》第15章里,Clark举了两项有关意外横财是否影响家庭长期命运的研究,结论都是:完全没有统计上可观察的正面影响。其中(more...)

Why you probably hate the sound of your own voice

为什么你可能会讨厌自己的声音

作者:Rachel Feltman @ 2015-6-16

译者:Marcel ZHANG(微博:@马赫塞勒张)

校对:沈沉(@你在何地-sxy)

来源:The Washington Post,https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/speaking-of-science/wp/2015/06/16/why-you-probably-hate-the-sound-of-your-own-voice/

Whether you’ve heard yourself talking on the radio or just gabbing in a friend’s Instagram video, you probably know the sound of your own voice — and chances are pretty good that you hate it.

不论是通过听到自己在广播上讲话,或是在朋友的Instagram视频里闲聊,你可能都已经了解了自己的声音,而且你很可能并不喜欢这个声音。

As the video above explains, your voice as you hear it when you speak out loud is very different from the voice the rest of the world perceives. That(more...)

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

Trivers’ Pursuit

罗伯特·特里夫斯:一生的追寻

作者:Matthew Hutson @ 2016-1-5

译者:Drunkplane(@Drunkplane-zny)

校对:慕白(@李凤阳他说)

来源:Psychology Today,https://www.psychologytoday.com/articles/201601/trivers-pursuit

Renegade scientist Robert Trivers is lauded as one of our greatest thinkers—despite irking academia with blunt talk and bad manners.

尽管罗伯特·特里夫斯直率的言谈和粗鲁的举止让学界恼怒,这位离经叛道的科学家仍被誉为最伟大的思想家之一。

To call Robert Trivers an acclaimed biologist is an understatement akin to calling the late Richard Feynman a popular professor of physics. As a young man in the 1970s, Trivers gave biology a jolt, hatching idea after idea that illuminated how evolution shaped the behavior of all species, including fidelity, romantic bonds, and willingness to cooperate among humans. Today, at 72, he continues to spawn ideas. And if awards were given for such things, he certainly would be on the short list for America’s most colorful academic.

把已故的理查德·费曼称为“一位受欢迎的物理学教授”,那是低估了他,同样地,如果把罗伯特·特里夫斯称为“一位广受赞誉的生物学家”也不够恰当。1970年代,当时不过是一个年轻人的特里夫斯就大大促进了生物学的研究,阐述了一个又一个想法,揭示了进化是如何塑造所有物种的行为,包括人类在性方面的忠贞、恋爱和合作的意愿。今天,他72岁,新的想法仍然不断从他脑中诞生。如果要为“想法”颁奖的话,他一定能进入“美国最有想法学者”短名单。

He was a member of the Black Panthers and collaborated with the group’s founder. He was arrested for assault after breaking up a domestic dispute. He faced machete-wielding burglers who broke into his home and stabbed one in the neck. He was imprisoned for 10 days over a contested hotel charge. And two men once held guns to his head in a Caribbean club that doubled as a brothel.

他曾是黑豹党一员,并曾同该组织的创立者合作。他曾因为在家庭纠纷中动手打人而被拘捕。他曾直面挥舞着弯刀的破门而入者,并在其中一人的脖子上扎了一刀。他曾因为一笔有争议的酒店费用而坐了十天牢。他还曾在加勒比一个俱乐部被人用枪顶着头——那个俱乐部同时也是妓院。

Fisticuffs aside, what propelled Trivers into the academic limelight were five papers he wrote as a young academic at Harvard—including research on altruism, sex differences, and parent-offspring conflict. This work won him the 2007 Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Crafoord Prize in Biosciences, the Nobel for evolutionary theory. The award came with half a million dollars and a ceremony attended by the queen.

除拳脚之外,让特里夫斯在学术圈声名大噪的是他年轻时在哈佛写就的五篇论文——包括关于利他主义、性别差异和亲子冲突的研究。这些成就为他赢得了2007年瑞典皇家科学院颁发的克拉福德生物学奖——进化理论的诺贝尔奖。奖金为50万美元,女王亦出席了颁奖典礼。

Steven Pinker has called him “one of the great thinkers in the history of Western thought.” Yet Trivers has not led the life of your typical contemplative academic. Mental breakdowns, public feuds, and near-death experiences have peppered his career, distracting him from his work even as they’ve nourished it.

史蒂文·平克曾称特里夫斯是“西方思想史上伟大的思想家之一”。然而特里夫斯不是你印象中那种典型的喜欢沉思的学者。精神崩溃、公开与人结怨和险些丧命的经历都让他的生涯显得与众不同,他的工作因此受到影响也因此获益。

No one is quite sure what to make of him, but all agree he is both brilliant and volatile, a sort of Steve Jobs without the colossal second coming. In a new memoir, Wild Life, he contrasts his existence with the “often solitary and intensely internal” one he sees in most scientists. “[That] kind of life,” he writes, “never appealed to me.”

没人确信该怎么评价他,但所有人都同意,他绝顶聪明,绝不安分,就像史蒂夫·乔布斯,但没有经历过乔布斯式卷土重来。在新回忆录《狂野生活》中,他对比了自己的生活同他在大多数科学家中所看到的“往往孤寂的、极其注重内心的”的生活,“那样的生活,”他写道,“从来不曾吸引我。”

To begin, Trivers’ revolutionary 1970s papers presented no new data. Trivers simply offered entirely novel ways of looking at what was already there, along with new avenues for moving science forward. His dissertation was so strong that when he showed up before the evaluating committee, which included such luminaries as E. O. Wilson and Ernst Mayr, they skipped the charade of making him defend it and simply offered their congratulations.

刚开始时,特里夫斯于1970年代发表的那几篇革命性论文中并没有提出新的数据。特里夫斯仅仅提供了一种全新的视角来看待既已存在的知识,一条推动科学进步的崭新道路。他的论证强而有力,以至当他面对评审委员会时——其中包括著名科学家爱德华·威尔逊和厄内斯特·迈尔——他们(more...)

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

Does Your Language Shape How You Think?

语言是否塑造了你的思维方式?

作者:Guy Deutscher @ 2010-8-26

译者:尼克基得慢(@尼克基得慢)

校对:沈沉(@你在何地-sxy)

来源:NYtimes,http://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/29/magazine/29language-t.html?_r=0

Seventy years ago, in 1940, a popular science magazine published a short article that set in motion one of the trendiest intellectual fads of the 20th century.At first glance, there seemed little about the article to augur its subsequent celebrity. Neither the title, “Science and Linguistics,” nor the magazine, M.I.T.’s Technology Review, was most people’s idea of glamour.

在七十年前的1940年,一份大众科学杂志发表了一篇短文,开启了二十世纪最新潮的思想风尚之一。乍看这篇文章,很难预料到它之后的名气。无论是文章标题《科学和语言学》,还是刊登的杂志《麻省理工科技评论》,都跟大多数人心目中的魅力不沾边。

And the author, a chemical engineer who worked for an insurance company and moonlighted as an anthropology lecturer at Yale University, was an unlikely candidate for international superstardom. And yet Benjamin Lee Whorf let loose an alluring idea about language’s power over the mind, and his stirring prose seduced a whole generation into believing that our mother tongue restricts what we are able to think.

而且,身为保险公司的化学工程师,同时兼职担任耶鲁大学人类学讲师,作者的这种身份并没有成为国际超级巨星的潜质。然而Benjamin Lee Whorf提出了一种关于语言对思维影响的诱人观点,而且他激动人心的文章诱使整整一代人相信,我们的母语限制了我们所能思考的内容。

In particular, Whorf announced, Native American languages impose on their speakers a picture of reality that is totally different from ours, so their speakers would simply not be able to understand some of our most basic concepts, like the flow of time or the distinction between objects (like “stone”) and actions(more...)

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

Nearly 1,000 People Move From Blue States to Red States Every Day. Here’s Why.

每天将近有1000人从蓝州搬到红州,这自有缘由。

作者:Stephen Moore @ 2015-10-9

译者:董慧颖

校对:沈沉(@你在何地-sxy)

来源:The Daily Signal,http://dailysignal.com/2015/10/09/nearly-1000-people-move-from-blue-states-to-red-states-every-day-heres-why/

The so-called “progressives” love to talk about how their policies will create a worker’s paradise, but then why is it that day after day, month after month, year after year, peop(more...)

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

Obama’s shameful Afghanistan retreat: This will embolden the Taliban, Al Qaeda and ISIS

奥巴马撤离阿富汗之举很可耻:这会鼓励塔利班、基地组织和伊斯兰国

作者:Frederick Kagan @ 2015-10-18

译者:沈沉(@你在何地-sxy)

校对:Whig zhou(@whigzhou)

来源:NEW YORK DAILY NEWS,http://www.nydailynews.com/opinion/frederick-kagan-obama-shameful-afghanistan-retreat-article-1.2400776

The headlines should read: “Obama to slash U.S. troops in Afghanistan by over 40% weeks before he hands over responsibility to a new President.” Instead they say: “Obama extends U.S. military presence in Afghanistan.” Talk about controlling the narrative.

新闻头条应该这么写:“在向新总统移交责任数周前,奥巴马将削减驻阿美军40%以上”。但实际上它们是这么写的:“奥巴马延长美军驻阿时间。”看看什么叫做控制叙事方式。

We’re missing the plot here. The 标签:

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

The Most Misunderstood Libertarian

最为人所误解的自由意志主义者

作者:Alberto Mingardi @ 2015-9-28

译者:沈沉(@你在何地-sxy)

校对:混乱阈值(@混乱阈值)

来源:Library of Law & Liberty,http://www.libertylawsite.org/book-review/the-most-misunderstood-libertarian/

To the surprise of many, scholarship on Herbert Spencer (1820-1903) has flourished in the last few years. A towering figure in Victorian Britain, Spencer was all but forgotten after his death. His works, which taken together form a “Synthetic Philosophy,” seemed alien to 20th century academics in an age of meticulous specialization. Also his commitment to individual liberty and (seriously) limited government has not been too common in the discipline that he helped establish, sociology. Talcott Parsons famously called him a victim of the very God he adored: evolution.

关于赫伯特·斯宾塞(1820-1903)的学术研究过去几年活跃了起来,这让许多人感到惊讶。斯宾塞是英国维多利亚时代的一位杰出人物,死后却几乎被人遗忘。他的各种著作构成一个“综合哲学”整体,与20世纪专业细分的学术界格格不入。并且,他对个体自由和(极度的)有限政府的信奉,在他所帮助建立的社会学学科中历来并不十分流行。塔儿科特·帕森斯曾出了名地把他称为他所推崇的那个上帝——进化——的牺牲品。

Toward the end of the 20th century, however, interest in Spencer began to revive. In 1974, J.D.Y. Peel published Herbert Spencer: The Evolution of a Sociologist and Robert Nisbet dealt at length with Spencer in his 1980 History of the Idea of Progress. In Anarchy, State and Utopia (1974), Robert Nozick adapted his “tale of the slave” on taxation and democracy from Spencer’s 1884 The Man vers(more...)

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

【2016-05-23】

1)达尔萨斯主义者(Darthusian)和古典自由主义者的根本区别在于:不许诺一个共同富裕普遍康乐的前景,并认为那注定是个虚假的许诺,

2)尽管我们相信(也乐意称颂)自由市场可以最大限度的拓展合作共赢的领域,也承认(统计上)自由社会的最穷困阶层也比非自由社会的普通人状况更好,但不会否认自由竞争终究会有失败者,自由化甚至可能在绝对水平上恶化一些人的处境,

3)马尔萨斯法则为这一判断提供了兜底保证,尽管不是唯一理由,

4)达尔文的启示在于,这完全不是(more...)

【2016-05-22】

@whigzhou: 大英帝国犯下的最大错误是让听任普鲁士统一德国,结果在一战时只好派自己的陆军上场,而不能像以前那样,只要花钱雇一批德国人打另一批德国人就行了。#后见之明

@whigzhou: 大英走的是弱共同体路线,这条路线有利于自由、繁荣和个人主义,以及为一个族群/文化高度混杂的社会建立普遍秩序,弱点是动员能力不足,难以像强共同体路线的德国那样建立庞大陆军,只能倚重于重资产轻人力的海军,拼钱不拼人头,(more...)

【2016-05-21】

@深大-子豪:辉总,冒昧问句,能否略微点评一下《无穷的开始:世界进步的本源》这本书?打扰了。

@whigzhou: 没读过,看了看介绍,感觉我不会有兴趣,这个人的念头听起来挺幼稚的

@whigzhou: 【不懂量子力学,我就随便嘀咕几句】1)多重世界,多么偷懒而幼稚的一张膏药啊,2)Deutsch对波普证伪主义的解读,好像还是很朴素的那种,3)同时推崇多重世界膏药和证伪主义,不觉得哪里有问题?4)有关模因已有了各种幼稚理论,Deutsch又添了一个,5)基因和模因居然能和多重世界扯上关系,惊了~

1)我把一些理论称为膏药,是因为我认为它们背离了可证伪性原则,

2)按我所采用的贝叶斯阐释,所谓可证伪性,就是能够就如何(结构性地)修正我们的(more...)