【2022-06-18】

@whigzhou: 出生在1980年前后移民家庭,且父母收入水平处于第25个百分位的男孩,成年后的收入平均百分位,

来源:www.aei.org/economics/why-do-the-kids-of-immigrants-move-up-the-economic-ladder/

评论:

1)显著高于45的部分显然无法以均值回归解释;

2)对于近水楼台,移民屏障好像对禀赋没(more...)

【2022-06-18】

@whigzhou: 出生在1980年前后移民家庭,且父母收入水平处于第25个百分位的男孩,成年后的收入平均百分位,

来源:www.aei.org/economics/why-do-the-kids-of-immigrants-move-up-the-economic-ladder/

评论:

1)显著高于45的部分显然无法以均值回归解释;

2)对于近水楼台,移民屏障好像对禀赋没(more...)

评论:

1)显著高于45的部分显然无法以均值回归解释;

2)对于近水楼台,移民屏障好像对禀赋没有多少筛选效果?

评论:

1)显著高于45的部分显然无法以均值回归解释;

2)对于近水楼台,移民屏障好像对禀赋没有多少筛选效果? 【2022-01-30】

@新浪财经 【物价飞涨!#美国火鸡培根涨价30%# #美国一个苹果卖9元#】

@InquilineX: 美国的人均GDP和可支配收入的中位数都是中国的6倍左右,所以要把美国商品的名义价格除以6得到的价格和国内同类商品比才有意义,比如原博说的一个苹果9元,那就相当于国内卖1.5元一个。

@whigzhou: 照你这么说,莫非收入增长的全部意义在且仅在于抵消价格提升?

@tertio:这个说的是心理感受吧,不涉及别的

@whigzhou: *所以要……才有意义*,这(more...)

【2021-09-09】

大学生(蓝线)和大专生(橙)的工资溢价都下降了,大专生下降更多,高中生(灰)相对工资率则大幅上升,

见:Firm heterogeneity and the college wage gap in Japan

见:Firm heterogeneity and the college wage gap in Japan【2021-07-09】

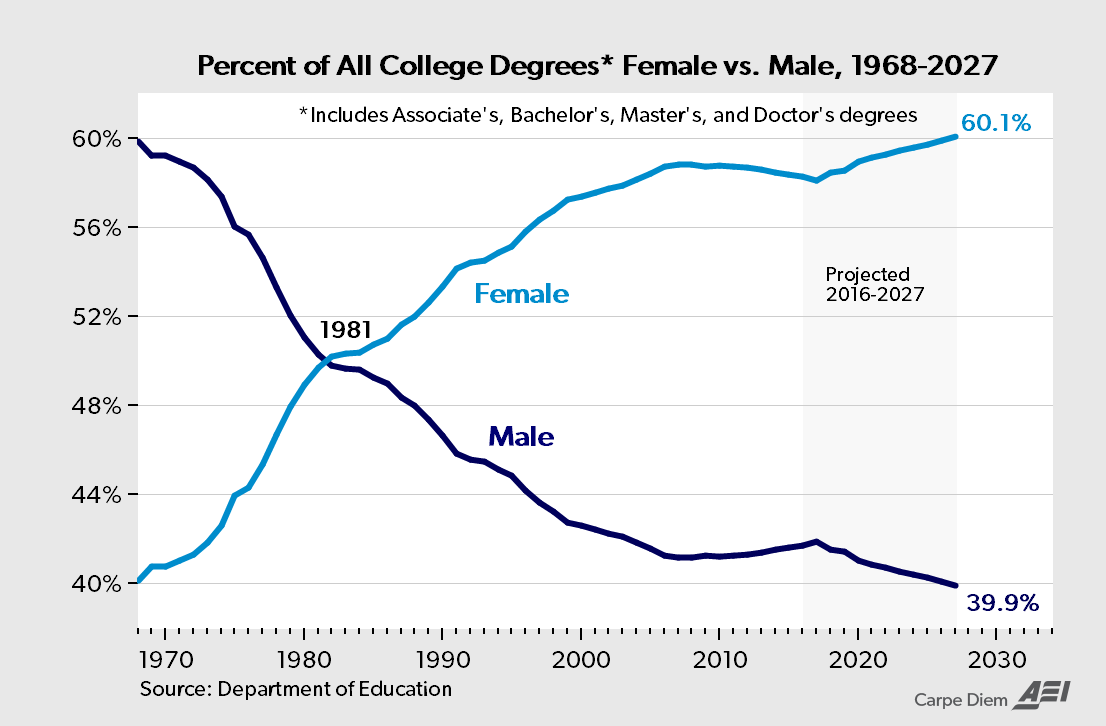

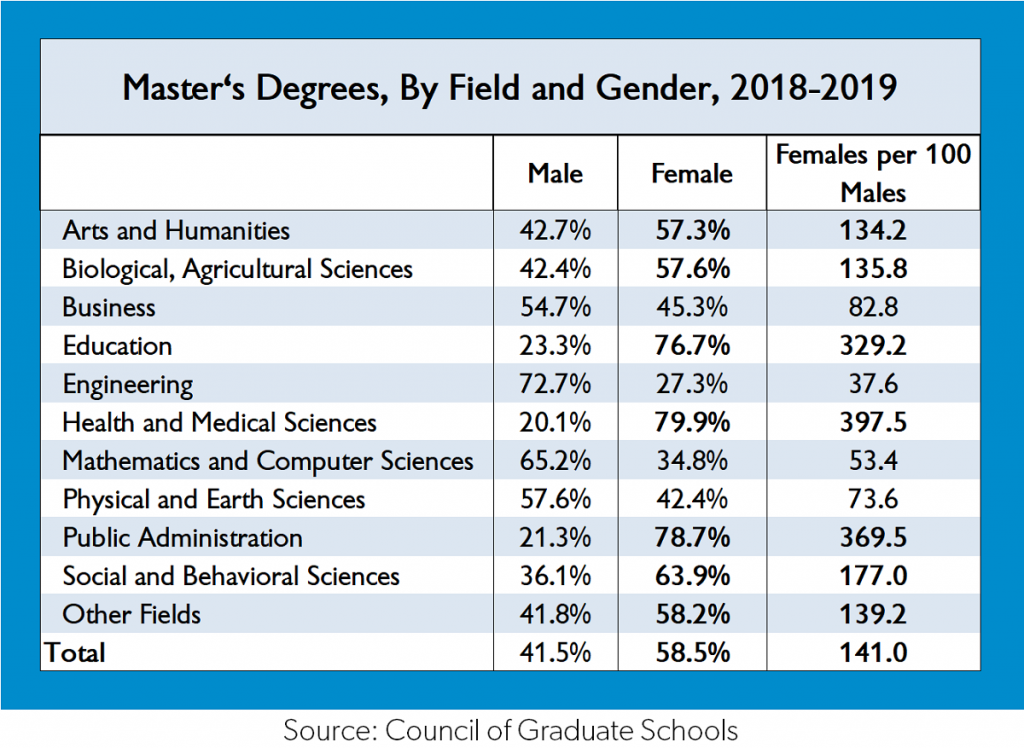

大学的女生比例越来越高,

这事情我听到过几种尝试性的解释,其中只有一种我感觉还说得过去:女生在学校通常比男生更乖更认真,所以,同等条件下,表现会更好,因而也更愿意继续读下去,

我从自己经历中得到的观察与之相符,以前同学中习惯性逃课逃学不交作业受罚的,绝大多数是男生,课堂上前几排座位基本上全是女生,抄作业和借笔记的对象一般也都是女生,

不过,我感觉这只能解释一小部分,另外几个因素还没听有人提到,但可能也很重要:

1)录取门槛降低会自动提高女生比例,因为男女智力平(more...)

这事情我听到过几种尝试性的解释,其中只有一种我感觉还说得过去:女生在学校通常比男生更乖更认真,所以,同等条件下,表现会更好,因而也更愿意继续读下去,

我从自己经历中得到的观察与之相符,以前同学中习惯性逃课逃学不交作业受罚的,绝大多数是男生,课堂上前几排座位基本上全是女生,抄作业和借笔记的对象一般也都是女生,

不过,我感觉这只能解释一小部分,另外几个因素还没听有人提到,但可能也很重要:

1)录取门槛降低会自动提高女生比例,因为男女智力平均水平差不多,但男生方差大,所以如果门槛很高,截取的是钟形曲线非常靠右的那段,而方差更大意味着尾巴更肥,被截到的比例自然就更高,随着门槛线向左移动,合格者中女生比例提高,

2)上大学至少有部分动机是为了提升未来的收入水平,关键是,在多大程度上不得不将高等教育作为求得一份体面收入的机会这一点上,男女面临的选项十分不同,女性对高等教育的依赖程度更大,这是因为,在不上大学的情况下,男生获得高收入的机会更多,在当前的产业形态下,留给低教育程度者的高收入职业,要么是重体力的,要么是高风险的,无论何种,都是高度男性化的,

@慕容飞宇gg:可能还和专业有关。大学里面的万精油专业(非专业的专业)主要是偏文科的心理学和偏理科的生物学。这些学科比较偏女性。

@whigzhou: 对,这个已经包括在第一点里了,门槛降低对各学科不是均匀的,有些降的多,纯数学和理论物理之类降不了多少,另外很多新专业都是低门槛的

@whigzhou: 有人问男生智商方差大的出处,这个说法我听到过很多次,我感觉这是学界共识,不过手头能翻到的来源只有 Earl Hunt (2011) Human Intelligence 第11章 11.3.3 节:

这事情我听到过几种尝试性的解释,其中只有一种我感觉还说得过去:女生在学校通常比男生更乖更认真,所以,同等条件下,表现会更好,因而也更愿意继续读下去,

我从自己经历中得到的观察与之相符,以前同学中习惯性逃课逃学不交作业受罚的,绝大多数是男生,课堂上前几排座位基本上全是女生,抄作业和借笔记的对象一般也都是女生,

不过,我感觉这只能解释一小部分,另外几个因素还没听有人提到,但可能也很重要:

1)录取门槛降低会自动提高女生比例,因为男女智力平均水平差不多,但男生方差大,所以如果门槛很高,截取的是钟形曲线非常靠右的那段,而方差更大意味着尾巴更肥,被截到的比例自然就更高,随着门槛线向左移动,合格者中女生比例提高,

2)上大学至少有部分动机是为了提升未来的收入水平,关键是,在多大程度上不得不将高等教育作为求得一份体面收入的机会这一点上,男女面临的选项十分不同,女性对高等教育的依赖程度更大,这是因为,在不上大学的情况下,男生获得高收入的机会更多,在当前的产业形态下,留给低教育程度者的高收入职业,要么是重体力的,要么是高风险的,无论何种,都是高度男性化的,

@慕容飞宇gg:可能还和专业有关。大学里面的万精油专业(非专业的专业)主要是偏文科的心理学和偏理科的生物学。这些学科比较偏女性。

@whigzhou: 对,这个已经包括在第一点里了,门槛降低对各学科不是均匀的,有些降的多,纯数学和理论物理之类降不了多少,另外很多新专业都是低门槛的

@whigzhou: 有人问男生智商方差大的出处,这个说法我听到过很多次,我感觉这是学界共识,不过手头能翻到的来源只有 Earl Hunt (2011) Human Intelligence 第11章 11.3.3 节:

【2020-04-09】

@whigzhou: 要想知道一个行业里是否存在网络效应,也就是会不会出现俗话所说的少数超级明星赢家通吃的局面,最简单的观察方法是看工资率的平均值与中位值的差距,因为明星效应会导致工资率分布偏离正态,至少在某个区间呈幂律分布,结果就是将均值拉高到明显超出中位值,我在新书第14章里花了两段文字讨论这个问题,下面几个数字我觉得挺有说服力:

按美国劳工部2018年的数据,若干行业小时工资率的均值与中位值对比:

演员:$29.34 v. $17.54,差67%

播音员:$24.82 v. $1(more...)

【2020-03-08】

@whigzhou: 最近发现越来越多自称libertarian的人在赞同universal basic income,捉急,且不论UBI在伦理上能否站住脚,也不论其长期的文化/社会后果是否可接受(这些以后有空再说),政策构想本身就幼稚的可笑。

不像福利主义者,libertarian们支持UBI的前提是它必须取代其他福利项目,而不是在福利清单上新添一项,因为他们的主要支持理由是效率,和其他有条件专项福利相比,直接发钱既方便,又很少负面(more...)

【2019-05-15】

@密西西比量子猪 贫穷最大的问题是缺钱[喵喵] 女士提问弗里德曼,美国贫穷买不起医疗保险的人怎么办。弗里德曼创造的一套负所得税,已经提上国会。但政客要捆绑上其他福利如住房补贴这些,弗里德曼死活不同意,最后一拍两散撤掉提案,留下一句名言穷人只是缺钱[doge]

弗里德曼强调种种的其他补贴只会导致腐败和低效率,唯一可行的是算清楚要补的钱,越贫穷的人越要有自己选择之权利

@密西西比量子猪:#ECON101# 负所得税=(收入保障数-个人实际收入)×负所得税率。比如负所得税率为50%,三口之家年收(more...)

@whigzhou: 最近的美国藤校申请舞弊案里据说不少好莱坞明星,这和我的预期有所出入,我原以为体育明星会更多,因为我一直觉得,和其他上层精英相比,体育明星在社会地位传承问题上处境比较尴尬,这是因为体育界的禀赋-报酬对应关系十分特殊,(据我粗略观察)报酬随禀赋提高而上升的曲线形状呈反L形,即大部分区段很低平,右侧末尾段突然上翘,意味着只有像乔丹这样的极小一撮成为富人,其他都是普通中产者,这一特点,使得体育明星很难指望下一代保持与自己相近的社会地位。

(more...)【2018-09-19】

@whigzhou: 1971年的阿拉斯加土著权利主张解决法案(Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act)可能是有史以来最大规模的按人头发钱方案,8万土著得到了14亿美元现金(相当于今天的87亿)和18万平方公里土地(通过13家地区公司和200多家村级公司的股份持有),这些土地上不久前刚发现石油,两代人过去了,阿拉斯加土著的整体经济/社会状况(相对于其他美国人)是否提升了?我花了好几十分钟,没搜到贴切的资(more...)

The Lottery

彩票

作者:Gregory Cochran @ 2015-04-22

译者:babyface_claire(@许你疯不许你傻)

校对:沈沉(@沈沉-Henrysheen)

来源:West Hunter,https://westhunt.wordpress.com/2015/04/22/the-lottery/

Lotteries can be useful natural experiments; we can use them to test the accuracy of standard sociological theories, in which rich people buy their kids extra smarts, bigger brains, better health, etc.

彩票可以视为一种有用的自然实验。我们可以用它们来检测标准社会学理论的准确度。这些理论认为,富人能给他们的孩子买到额外的智慧、更大的大脑和更健康的身体,等等。

David Cesarini, who I met at that Ch(more...)

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

【2016-05-24】

@whigzhou: 自由市场制度下,财产的初始分配根本不重要,整个宾夕法尼亚的土地起初全归小威廉·潘恩一人所有,这一事实对该州后来的社会结构有多大影响?彩票发明那么多年了,每年都有人中亿万大奖,你听说过哪个显贵家族是靠祖上中彩票发达的?

@whigzhou: 在《儿子照样升起》第15章里,Clark举了两项有关意外横财是否影响家庭长期命运的研究,结论都是:完全没有统计上可观察的正面影响。其中(more...)

“小小奇迹”不再:美国劳动收入占比下降

A Bit of a Miracle No More:The Decline of the Labor Share

作者:Roc Armenter @ 2015-三季刊

译者:Veidt(@Veidt)

校对:混乱阈值(@混乱阈值)

来源:Business Review,https://www.philadelphiafed.org/-/media/research-and-data/publications/business-review/2015/q3/brq315_a_bit_of_a_miracle_no_more.pdf

How is income divided between labor and capital? Every dollar of income earned by U.S. households can be classified as either labor earnings — wages and other forms of compensation — or capital earnings — interest or dividend payments and rent. The split between labor and capital income informs economists’ thinking on several topics and plays a key role in debates regarding income inequality and long-run economic growth. Unfortunately, distinguishing between labor and capital income is not always an easy task.

收入是如何在劳动和资本之间分配的?美国家庭所赚取的每一块钱都可以被归类为劳动收入(工资或其它形式的劳动补偿)或资本收益(利息、股利和租金等)。收入在劳动和资本之间的分配为经济学家们关于许多经济学议题的思考提供了重要信息,并且在关于收入不平等和长期经济增长这些问题的争论中扮演着核心角色。不幸的是,将劳动收入与资本收入区分开并非总是一件易事。

Until recently, the division between labor and capital income had not received much attention. The reason was quite simple: Labor’s share never ventured far from 62 percent of total U.S. income for almost 50 years — through expansions, recessions, high and low inflation, and the long transition from an economy primarily based on manufacturing to one mainly centered on services.

一直以来,区分劳动收入和资本收入的问题并没有受到太大关注,直到最近才有所改观。原因很简单:在将近50年中,美国劳动收入在总收入中所占的比例从来不会偏离62%这个数字太远——不论经济是在扩张还是衰退,也不论通胀率是高是低,在美国经济从以制造业为基础向主要以服务业为核心的漫长转变过程中,这个比例一直很稳定。

As it happened, the overall labor share remained stable as large forces pulling it in opposite directions canceled each other out — a coincidence that John Maynard Keynes famously called “a bit of a miracle.” But the new millennium marked a turning point: Labor’s share began a pronounced fall that continues today.

劳动收入占比在多种强大力量的反向拉扯和相互抵消之下总体保持了稳定这件事情本身——按照约翰·梅纳德·凯恩斯的著名说法——可以称得上是个“小小奇迹”。但是新千年的到来却标志着一个重要的转折点:劳动收入占比开始明显下降,并且这个趋势一直持续到了现在。

Why did the labor share lose its “miraculous” stability and embark on a steep decline? To investigate this shift, economists must first be sure they are measuring the labor share correctly. Could measurement problems distort our understanding of what has happened to the labor share over time?

为什么劳动收入占比会失去它“奇迹般”的稳定性而开始急剧下降?要研究这一转变,经济学家们的首要任务是确保他们测量劳动收入占比的方法是准确的。测量方法存在问题会歪曲我们对于长期以来劳动收入占比所发生的变化的理解吗?

In this article, I explain the inherent challenges in measuring the labor share and introduce several alternative definitions designed to address some of the measurement problems. As we will see, the overall trend is confirmed across a wide range of definitions.

在这篇文章中,我将解释在测量劳动收入占比时所面临的内在挑战,并介绍几种旨在解决其中一些测量问题的替代性定义。正如我们将看到的,基于一系列不同定义的测量结果都证实了劳动收入占比总体上的下降趋势。

Economists do not yet have a full understanding of the causes behind the labor share’s decline. We can make some progress, though, by noting the impact of wage and productivity trends and shifts between industries. Finally, I discuss several popular hypotheses, based on concurrent phenomena, such as widening wage inequality and globalization, that may account for the labor share’s sharp decline.

经济学家们至今还未能全面地理解劳动收入占比下降背后的原因。即便如此,通过研究工资和生产率的变化趋势以及产业的变迁,我们仍然可以取得一些进展。最后,我将讨论一些流行的假设。这些基于诸如薪资不平等程度加深以及全球化等并发现象的假设也许能解释劳动收入占比的急剧下降。

MEASURING THE U.S. LABOR SHARE

测量美国的劳动收入占比

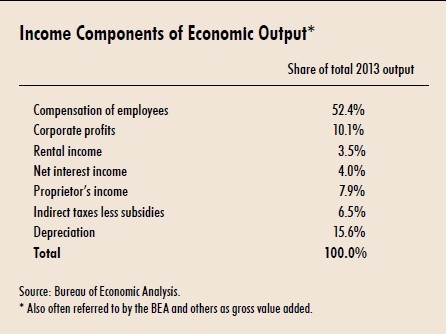

By construction, all income accounted for in the U.S. economy must be earned either by capital or labor. In some cases, we can easily see whether our income comes from labor or capital: when we earn a wage or a bonus through our labor or when we earn interest from our savings or investment account, which is attributed to capital income, despite the fact that most of us would not think of ourselves as investors.

从定义上说,美国经济中任何的收入要么被资本赚取了,要么就是被劳动赚取了[i]。在一些情形中,我们可以很容易地看出我们的收入是来自于劳动还是资本:当我们通过劳动赚到一份工资或者奖金时,这部分收入显然来自于劳动;虽然我们中的大部分人并不认为自己是投资者,但当我们从储蓄或投资账户中获得利息或投资收益时,这部分收入很明显应该被归为资本收入。

However, it is not always immediately apparent that all income eventually accrues to either capital or labor. For example, when we buy our groceries — creating income for the grocer — we are only vaguely aware that we are also paying the producers, farm workers, and transporters as well as for the harvesters, trucks, trains, coolers, and other capital equipment involved in producing and distributing what we purchase. However, when the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) constructs the national income and product accounts, it combines data from expenditures and income to ensure that every dollar spent is also counted as a dollar earned by either capital or labor.

然而,所有的收入最终都会被归为资本收入或劳动收入这一点并不总是那么显而易见。举个例子,当我们从杂货店里买东西时——这显然为杂货店主创造了收入——我们仅仅模糊地意识到我们所付的钱同样也为货物的生产者、农场工人、运输工人创造了收入,除此以外,我们还为投资于收割机、卡车、制冷装置和其它一些参与我们所购买货物的生产和分销过程的设备的资本创造了收入。而国家经济分析局(BEA)在构建国民收入和生产账户时将来自支出和来自收入的数据合并在一起,以保证任何一美元的支出也同样要么被资本赚取,要么被劳动赚取。

Of course, nothing is ever so simple economic statistics. First, we lack the detail necessary to split some components of the income data between labor and capital returns. As I (more...)

Proprietor’s income is defined as the income of sole proprietorships and partnerships — in other words, the income of self-employed individuals. There is no question that their income is the result of both labor and capital. For example, a freelance journalist may work long hours to document and write a story using a computer and a camera that she or he financed through savings. However, self-employed individuals have no need, economic or fiscal, to distinguish between wages and profits. However, economists do.

经营者收入被定义为个人独资以及合伙企业的收入——换句话说,也就是个体经营者的收入[iv]。毫无疑问,他们的收入同时是劳动投入和资本投入的结果。举例来说,一名自由记者可能会为了撰写一篇报导工作很长时间,而他使用的电脑和相机则是用自己的积蓄购买的。但是,个体经营者完全没有经济或财务上的理由将自己的收入区分为工资和利润。遗憾的是,经济学家们却需要这么做。

The main BLS measure

国家劳动统计局的主流测量方法

The BLS is well aware of these problems and goes to great lengths to disentangle proprietor’s income into its labor and capital income components. First, the BLS uses its data on payroll workers to compute an average hourly wage. The BLS then assumes that a self-employed worker would pay himself or herself the implicit wage rate. Then, using data on hours worked by self-employed workers, it obtains a measure of the labor compensation for self-employed individuals simply by multiplying the average hourly wage by the number of hours worked by the self-employed. The result is then assigned to labor income. The rest of the proprietor’s income is considered capital income.

国家劳动统计局对这些问题心知肚明,它在如何将经营者收入分解为劳动收入部分和资本收入部分这个问题上走得更远。首先,它使用领薪劳工的数据计算出一个平均时薪。然后假设一名自雇者将会按照这个时薪来给自己发工资。之后,使用自雇工人工作时长的数据并通过简单地将自雇者的平均时薪和工作时长相乘,国家劳动统计局就获得了对自雇者劳动报酬的测量数据。这个结果会被归为劳动收入,而这名经营者收入中的剩余部分则被认为是资本收入[v]。

Figure 1 plots the BLS’s headline labor share at an annual frequency from 1950 to 2013. Up until 2001, the labor share displayed some ups and downs, and perhaps a slight downward trend, but it never strayed far from 62 percent. From 2001 onward, though, the labor share has been steadily decreasing, dropping below 60 percent for the first time in 2004 and continuing its fall to 56 percent as of 2014.

图1描述了按国家劳动统计局主流方法计算出的自1950年到2013年的年度劳动收入占比[vi]。直到2001年,劳动收入占比一直都在一个很轻微的下行趋势中起起落落,但是它从来没有离62%这个数字太远。但自2001年以后,劳动收入占比一直在持续下降,在2004年首次跌破60%,并一直持续跌落到2014年的56%[vii]。

Proprietor’s income is defined as the income of sole proprietorships and partnerships — in other words, the income of self-employed individuals. There is no question that their income is the result of both labor and capital. For example, a freelance journalist may work long hours to document and write a story using a computer and a camera that she or he financed through savings. However, self-employed individuals have no need, economic or fiscal, to distinguish between wages and profits. However, economists do.

经营者收入被定义为个人独资以及合伙企业的收入——换句话说,也就是个体经营者的收入[iv]。毫无疑问,他们的收入同时是劳动投入和资本投入的结果。举例来说,一名自由记者可能会为了撰写一篇报导工作很长时间,而他使用的电脑和相机则是用自己的积蓄购买的。但是,个体经营者完全没有经济或财务上的理由将自己的收入区分为工资和利润。遗憾的是,经济学家们却需要这么做。

The main BLS measure

国家劳动统计局的主流测量方法

The BLS is well aware of these problems and goes to great lengths to disentangle proprietor’s income into its labor and capital income components. First, the BLS uses its data on payroll workers to compute an average hourly wage. The BLS then assumes that a self-employed worker would pay himself or herself the implicit wage rate. Then, using data on hours worked by self-employed workers, it obtains a measure of the labor compensation for self-employed individuals simply by multiplying the average hourly wage by the number of hours worked by the self-employed. The result is then assigned to labor income. The rest of the proprietor’s income is considered capital income.

国家劳动统计局对这些问题心知肚明,它在如何将经营者收入分解为劳动收入部分和资本收入部分这个问题上走得更远。首先,它使用领薪劳工的数据计算出一个平均时薪。然后假设一名自雇者将会按照这个时薪来给自己发工资。之后,使用自雇工人工作时长的数据并通过简单地将自雇者的平均时薪和工作时长相乘,国家劳动统计局就获得了对自雇者劳动报酬的测量数据。这个结果会被归为劳动收入,而这名经营者收入中的剩余部分则被认为是资本收入[v]。

Figure 1 plots the BLS’s headline labor share at an annual frequency from 1950 to 2013. Up until 2001, the labor share displayed some ups and downs, and perhaps a slight downward trend, but it never strayed far from 62 percent. From 2001 onward, though, the labor share has been steadily decreasing, dropping below 60 percent for the first time in 2004 and continuing its fall to 56 percent as of 2014.

图1描述了按国家劳动统计局主流方法计算出的自1950年到2013年的年度劳动收入占比[vi]。直到2001年,劳动收入占比一直都在一个很轻微的下行趋势中起起落落,但是它从来没有离62%这个数字太远。但自2001年以后,劳动收入占比一直在持续下降,在2004年首次跌破60%,并一直持续跌落到2014年的56%[vii]。

An alternative measure

一种替代测量方法

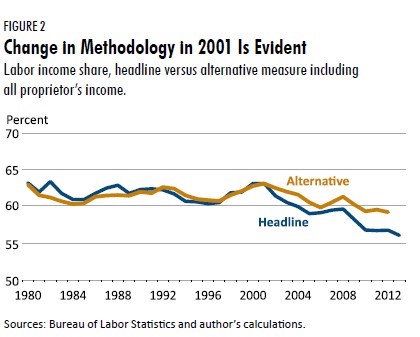

Michael Elsby, Bart Hobijn, and Aysegul Sahin have pointed out that some of the fall in the labor share in the past 15 years is due to how the BLS splits proprietor’s income. Indeed, until 2001, the BLS’s methodology assigned most of proprietor’s income to the labor share, a bit more than four-fifths of it. Since then, less than half of proprietor’s income has been classified as labor income.

Michael Elsby, Bart Hobijn和Aysegul Sahin指出,劳动收入占比在过去15年中的下降可部分归因于国家劳动统计局分割经营者收入的方法。事实也的确如此,直到2001年,国家劳动统计局都将经营者收入中的大部分归为劳动收入,比例略高于五分之四。而2001年之后,经营者收入中仅有不到一半的比例被归为劳动收入。

How important is this shift? It is fortunately very easy to produce an alternative measure of the labor share in which a constant fraction of proprietor’s income accrues to labor. Setting that fraction to its historical average prior to 2000 — 85 percent — we can figure out what would be the current labor share under this alternative assumption.

这一变化的影响有多大?幸运的是,我们可以很容易地用一种替代测量方法来对劳动收入占比进行估值,这种方法就是把业主收入按照一个固定比例计算为劳动收入。如果将该比例设定为2000年以前的历史平均值——85%——我们就能计算用该替代方法测量的当前的劳动收入占比。

Figure 2 contrasts the previous headline number against this alternative measure from 1980 onward.

图2对比了国家统计局公布的自1980年以来的劳动收入占比和使用替代方法得到的同时期劳动收入占比。

An alternative measure

一种替代测量方法

Michael Elsby, Bart Hobijn, and Aysegul Sahin have pointed out that some of the fall in the labor share in the past 15 years is due to how the BLS splits proprietor’s income. Indeed, until 2001, the BLS’s methodology assigned most of proprietor’s income to the labor share, a bit more than four-fifths of it. Since then, less than half of proprietor’s income has been classified as labor income.

Michael Elsby, Bart Hobijn和Aysegul Sahin指出,劳动收入占比在过去15年中的下降可部分归因于国家劳动统计局分割经营者收入的方法。事实也的确如此,直到2001年,国家劳动统计局都将经营者收入中的大部分归为劳动收入,比例略高于五分之四。而2001年之后,经营者收入中仅有不到一半的比例被归为劳动收入。

How important is this shift? It is fortunately very easy to produce an alternative measure of the labor share in which a constant fraction of proprietor’s income accrues to labor. Setting that fraction to its historical average prior to 2000 — 85 percent — we can figure out what would be the current labor share under this alternative assumption.

这一变化的影响有多大?幸运的是,我们可以很容易地用一种替代测量方法来对劳动收入占比进行估值,这种方法就是把业主收入按照一个固定比例计算为劳动收入。如果将该比例设定为2000年以前的历史平均值——85%——我们就能计算用该替代方法测量的当前的劳动收入占比。

Figure 2 contrasts the previous headline number against this alternative measure from 1980 onward.

图2对比了国家统计局公布的自1980年以来的劳动收入占比和使用替代方法得到的同时期劳动收入占比。

First, we confirm that through 2000, both the headline and the alternative measure pretty much coincide. Since 2001, though, they diverge, with the drop being noticeably smaller in the alternative measure. Indeed, this divergence suggests that at least one-third and possibly closer to half of the drop in the headline labor share is due to how the BLS treats proprietor’s income.

首先,我们确认直到2000年,按国家劳动统计局的主流方法和这里的替代方法得到的结果基本是吻合的。而自从2001年开始,两者之间的差异开始扩大。按替代方法计算的结果中,劳动收入占比的下降幅度明显要小得多。两者间的差异事实上表明,按国家经济统计局的主流方法计算所得的结果中至少三分之一,甚至很可能接近一半的劳动收入占比降幅是由该方法对待经营者收入的方式所引起的。

Alternatively, we can also proceed by the centuries-tested scientific method of ignoring the problem altogether and compute the compensation or payroll share instead of the labor share. That is, we can assume that none of proprietor’s income accrues to labor.

另外,我们还可以采用一种经过多个世纪检验的“科学方法”——彻底忽略以上不同测量方法的问题,仅仅计算受雇劳工获取的劳动报酬占比,而不计算劳动收入占比。那么,我们就可以假设,经营者的所有收入都不会被归为劳动收入。

This is actually a quite common approach, since detailed payroll data exist for all industries, allowing us to pinpoint which sectors of the economy are responsible for the dynamics of labor income. The compensation share is, obviously, lower than the labor share — but its evolution across time is very similar: stable until the turn of the millennium and a decline since then.

实际上这也是一种很常用的方法。由于所有的行业都有非常详细的工资单数据,这让我们能够详细地查明经济中的哪些部门对劳动收入的变化产生了影响。劳动报酬收入占总收入的比重显然要低于总的劳动收入,但是它随时间变化的轨迹与劳动收入占比的变化轨迹非常相似:在新千年到来之前一直都很稳定,而从那以后就开始持续下降。

Yet another measure

另一种替代测量方法

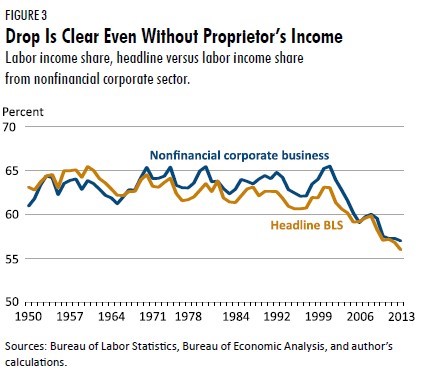

There is yet another possible way to circumvent the ambiguity regarding proprietor’s income. The data allow us to zoom in to the non-financial corporate business sector. By law, corporations must declare payroll and profits separately for fiscal purposes, so there is actually no proprietor’s income. The downside is, of course, that we are working with only a subset of the economy, albeit a very large one.

还有另外一种可能的方法可以绕过处理经营者收入时面临的模棱两可问题。数据让我们可以更仔细地观察非金融企业部门。在法律上,由于财务方面的原因,公司必须分开报告工资单和利润,因此实际上这里就不存在经营者收入这个概念。但这个方法的缺点在于,我们只能研究整体经济中的一个子集,尽管这是一个相当大的子集[viii]。

Figure 3 plots the BLS headline measure and the labor share of income of the non-financial corporate sector from 1950 to the latest data available. The two series overlap for most of the period, though the headline labor share was consistently about 1 percentage point below that of non-financial firms from 1980 onward. In any case, the message since 2000 is unmistakable: The large drop in the headline measure is fully reflected in this alternative measure.

图3描述了从1950年开始到最近可获取数据的时间段内,分别使用国家劳动统计局的主流方法和非金融企业部门的劳动收入占比数据所得到的结果。虽然自1980年开始,主流方法测得的的劳动收入占比相对非金融企业中的劳动收入占比一直都低了1%左右,但在大多数时间段内,两条曲线的走势都是趋同的。不论在哪种情形下,2000年以来的数据所传递的信号都是明确无误的:主流方法中劳动收入占比的巨大降幅在这种替代方法中也得到了完全的反映。

First, we confirm that through 2000, both the headline and the alternative measure pretty much coincide. Since 2001, though, they diverge, with the drop being noticeably smaller in the alternative measure. Indeed, this divergence suggests that at least one-third and possibly closer to half of the drop in the headline labor share is due to how the BLS treats proprietor’s income.

首先,我们确认直到2000年,按国家劳动统计局的主流方法和这里的替代方法得到的结果基本是吻合的。而自从2001年开始,两者之间的差异开始扩大。按替代方法计算的结果中,劳动收入占比的下降幅度明显要小得多。两者间的差异事实上表明,按国家经济统计局的主流方法计算所得的结果中至少三分之一,甚至很可能接近一半的劳动收入占比降幅是由该方法对待经营者收入的方式所引起的。

Alternatively, we can also proceed by the centuries-tested scientific method of ignoring the problem altogether and compute the compensation or payroll share instead of the labor share. That is, we can assume that none of proprietor’s income accrues to labor.

另外,我们还可以采用一种经过多个世纪检验的“科学方法”——彻底忽略以上不同测量方法的问题,仅仅计算受雇劳工获取的劳动报酬占比,而不计算劳动收入占比。那么,我们就可以假设,经营者的所有收入都不会被归为劳动收入。

This is actually a quite common approach, since detailed payroll data exist for all industries, allowing us to pinpoint which sectors of the economy are responsible for the dynamics of labor income. The compensation share is, obviously, lower than the labor share — but its evolution across time is very similar: stable until the turn of the millennium and a decline since then.

实际上这也是一种很常用的方法。由于所有的行业都有非常详细的工资单数据,这让我们能够详细地查明经济中的哪些部门对劳动收入的变化产生了影响。劳动报酬收入占总收入的比重显然要低于总的劳动收入,但是它随时间变化的轨迹与劳动收入占比的变化轨迹非常相似:在新千年到来之前一直都很稳定,而从那以后就开始持续下降。

Yet another measure

另一种替代测量方法

There is yet another possible way to circumvent the ambiguity regarding proprietor’s income. The data allow us to zoom in to the non-financial corporate business sector. By law, corporations must declare payroll and profits separately for fiscal purposes, so there is actually no proprietor’s income. The downside is, of course, that we are working with only a subset of the economy, albeit a very large one.

还有另外一种可能的方法可以绕过处理经营者收入时面临的模棱两可问题。数据让我们可以更仔细地观察非金融企业部门。在法律上,由于财务方面的原因,公司必须分开报告工资单和利润,因此实际上这里就不存在经营者收入这个概念。但这个方法的缺点在于,我们只能研究整体经济中的一个子集,尽管这是一个相当大的子集[viii]。

Figure 3 plots the BLS headline measure and the labor share of income of the non-financial corporate sector from 1950 to the latest data available. The two series overlap for most of the period, though the headline labor share was consistently about 1 percentage point below that of non-financial firms from 1980 onward. In any case, the message since 2000 is unmistakable: The large drop in the headline measure is fully reflected in this alternative measure.

图3描述了从1950年开始到最近可获取数据的时间段内,分别使用国家劳动统计局的主流方法和非金融企业部门的劳动收入占比数据所得到的结果。虽然自1980年开始,主流方法测得的的劳动收入占比相对非金融企业中的劳动收入占比一直都低了1%左右,但在大多数时间段内,两条曲线的走势都是趋同的。不论在哪种情形下,2000年以来的数据所传递的信号都是明确无误的:主流方法中劳动收入占比的巨大降幅在这种替代方法中也得到了完全的反映。

So, despite the inherent measurement problems, the data are clear: First, the labor share was stable from 1950 to at least near the end of the 1980s. Second, it has fallen precipitously since 2001. While the exact magnitude of the drop may be open to debate, there is no doubt that the downward trend in the labor share since 2001 is unprecedented in the data and, at the time of this writing, shows no signs of abating.

所以如果将这些测量方法所固有的问题放在一边,数据的含义是非常清晰的:首先,从1950年到至少1980年代末,劳动收入占比一直都保持了稳定。第二,从2001年开始,劳动收入占比开始急剧下降。虽然精确的降幅到底是多少仍然有待讨论,但毫无疑问的是,从数据看来,2001年之后的劳动收入占比下降趋势是前所未有的。而直到撰写本文时,这个趋势也丝毫也没有减弱的迹象。

A BIT OF A MIRACLE: 1950-1987

“小小奇迹”:1950-1987

We now take a closer look at the period in which the labor share was stable — roughly from the end of World War II to the late 1980s — by breaking it down by sector. In doing so, we will understand the logic behind the “bit of a miracle” quip. The cutoff date is necessarily 1987, since the industry classification changed in that year. Fortunately, it is also the approximate end date of the stable period for the labor share.

大约从二战结束一直到1980年代末这一时期的美国劳动收入占比一直都很稳定。现在我们来分阶段地仔细审视一下这个时期。这将有助理解这个“小小奇迹”背后的逻辑。我们只能将这一时期的终点选在1987年,因为在1987年,行业的划分标准发生了变化。幸运的是,这一年也恰好几乎是劳动收入占比保持稳定的时代终结的年份。

Since the end of WWII, the U.S. has gone through large structural changes to its sectorial composition. The most significant was the shift from manufacturing to services. In 1950, manufacturing accounted for more than two-thirds of the non-farm business sector. By 1987, manufacturing was just half of the non-farm business sector. Over the same period, services increased from 21 percent to 40 percent of the non-farm business sector.

自从二战结束后,美国经济的产业构成经历了巨大的结构性变化。最明显的变化是经济从制造业向服务业的转型。在1950年,制造业在非农经济中占据的比重超过了三分之二。而到1987年,制造业在非农经济中仅仅占据了一半的比重。同一时期,服务业在非农经济部门中所占的比重则从21%提升到了40%[ix]。

The reader would not be surprised to learn that different sectors use labor and capital in different proportions. In 1950, the manufacturing sector averaged a labor share of 62 percent, with some sub-sectors having even higher labor shares, such as durable goods manufacturing, with a labor share of 77 percent. Services instead relied more on capital and thus had lower labor shares: an average of 48 percent.

对于不同的经济部门中劳动和资本的构成比例不同这一点,相信读者们并不会感到吃惊。在1950年,制造业部门中的平均劳动收入占比是62%,而其中某些子部门的劳动收入占比还要更高,例如在耐用品制造业中,劳动收入占比到了77%[x]。与之相反,服务业则更加依赖于资本,因而其劳动收入占比也更低:平均水平是48%。

Thus, from 1950 to 1987, the sector with a high labor share (manufacturing) was cut in half, while the sector with a low labor share (services) doubled. The aggregate labor share is, naturally, the weighted average across these sectors. Therefore, we would have expected the aggregate labor share to fall. But as we already know, it did not.

也就是说,从1950年到1987年间,劳动收入占比较高的部门(制造业)在经济中的占比下降了接近一半,而劳动收入占比较低的部门(服务业)在经济中的占比则上升了一倍。加总的劳动收入占比很自然地应该等于不同部门劳动收入占比的加权平均值。既然如此,我们应该可以预期,加总的劳动收入占比会下降。但正如我们已经知道的,它并没有下降。

The reason is that, coincidentally with the shift from manufacturing to services, the labor share of the service sector rose sharply, from 48 percent in 1950 to 56 percent in 1987. Education and health services went from labor shares around 50 percent to the highest values in the whole economy, close to 84 percent. In manufacturing, the labor share was substantially more stable, increasing by less than 2 percentage points over the period.

而其中的原因则是在经济从制造业向服务业的转型过程中,服务业中的劳动收入占比却巧合地经历了大幅的上升,从1950年的48%上升到了1987年的56%。教育和医疗服务业中的劳动收入占比从50%左右上升到了整个经济各部门中的最高水平,接近84%[xi]。制造业中的劳动收入占比则持续保持稳定,在整个期间内上升了不到2%。

And this is the “bit of a miracle” — that the forces affecting the labor share across and within sectors just happened to cancel each other out over a period of almost half a century.

而这就是所谓的“小小奇迹”——在接近半个世纪的时间内,部门间和部门内影响劳动收入占比的各种力量恰恰抵消了各自的影响。

A BIT OF A MIRACLE NO MORE: 1987-2011

“小小奇迹”不再:1987-2011

I start by repeating the previous exercise, now over the period 1987 to 2011. As it had from 1950 to 1987, the manufacturing sector kept losing ground to the service sector, albeit at a slower rate.

下面我首先会采取和之前相同的方法来分析美国经济的劳动收入占比,只是将时间段换成1987年-2011年。和1950年-1987年间一样,尽管速度有所下降,但制造业部门在经济中的占比仍然持续被服务业部门所抢占。

By 2011, services accounted for more than two-thirds of U.S. economic output and an even larger fraction of total employment. However, the differences in the labor share between the two sectors were much smaller by the early 1990s, and thus the shift from manufacturing to services had only small downward effects on the overall labor share.

到2011年,服务业在美国经济总产出中所占的比重已经超过了三分之二,而在总就业中的占比甚至更高。然而这两个部门之间劳动收入占比的差异相比1990年代初却缩小了不少,因此,经济从制造业向服务业的转型对总体劳动收入占比仅仅会造成很小的下行作用。

We readily find out which part of the economy is behind the decline of the labor share once we look at the change in the labor share within manufacturing, which dropped almost 10 percentage points. Virtually all the major manufacturing sub-sectors saw their labor shares fall; for non-durable goods manufacturing it dropped from 62 percent to 40 percent. The labor share within the service sector kept increasing, as it had before 1987, but very modestly, only enough to cancel the downward pressure from the shift across sectors. Indeed, had the labor share of income in manufacturing stayed constant, the overall labor share would have barely budged.

只要看看在制造业中劳动收入占比的变化,我们就能很容易地发现经济中的哪一部分是造成劳动收入占比下降的主因。在制造业中,劳动收入占比下降了接近10个百分点。基本上所有主要的制造业子部门都经历了劳动收入占比的下降。在非耐用品制造业中,劳动收入占比从62%下降到了40%。而服务业部门的劳动收入占比相对1987年之前的水平仍然保持了增长,但是增幅非常缓慢,仅仅足够抵消掉由经济从制造业向服务业转型所产生的下行压力。的确,假如制造业中的劳动收入占比能够保持不变,整体经济中的劳动收入占比就几乎不会下降。

Note that in one sense, the bit of a miracle actually continued from 1987 onward: As manufacturing continued to shrink, decreasing the share of income accruing to labor, services picked up the slack by increasing their share of income accruing to labor, albeit more modestly than before. What ended the “miracle” was the precipitous decline in the labor share within manufacturing.

从这个意义上说,“小小奇迹”实际上在1987年之后也得到了延续:制造业在整体经济中占比的持续收缩减少了总收入中劳动收入的比例,而服务业则在一定程度上通过提升部门内的劳动收入占比收拾了残局,虽然提升的速度相比之前已经减缓了许多。终结“奇迹”的实际上是制造业内部劳动收入占比的急剧下降。

Wages and productivity

工资与劳动生产率

It is worth investigating a bit further what determinants are behind the fall in the labor share within manufacturing, since it played such an important role in the decline of the overall labor share. To this end, note that the change in the labor share in a particular sector is linked to the joint evolution of wages and labor productivity.

由于制造业内部的劳动收入占比下降在整体劳动收入占比的下降中发挥了如此重要的作用,更深入地研究其中的决定因素就显得很有价值了。从这个意义上说,我们需要注意到,某个特定部门内的劳动收入占比是与工资和劳动生产率的联合演化联系在一起的。

Consider a machine operator working in a factory for one hour to produce goods that will have a gross value to the factory owner of $100. If he is paid $60 per hour, labor’s share is approximately 60 percent. For the labor share to change, there are only two possibilities: Either the value of the goods produced must change or the hourly wage must. Conversely, for the labor share to stay constant, the value of the goods and the hourly wage have to move in unison.

假如一名机器操作员在工厂中工作一小时能够生产出对于工厂主而言价值100美元的产品,如果他的时薪是60美元,那么劳动收入占比就大约是60%。一旦劳动收入占比发生变化,仅仅有两种可能的情况:要么是产出的价值发生了变化,要么是操作员的时薪发生了变化。反过来说,如果劳动收入占比保持不变,产出的价值和操作员的时薪就必须总是等比例变化[xii]。

So which one — productivity or wages — brought down the labor share in manufacturing? Fortunately, we do have reliable data on output, wage rates, and hours worked in manufacturing. Figure 4 displays the evolution of labor productivity (that is, output per hour) and wage rates from 1950 onward. Both series are set such that their value in 1949 equals 100.

那么在生产率和工资水平中,究竟是哪一项将制造业中的劳动收入占比拖了下来呢?幸运的是,我们拥有制造业中关于产出,单位时间工资和工作时长的可靠数据。图4显示了自1950年以来劳动生产率(也就是每小时产出)和单位时间工资的演化过程[xiii]。两条曲线都将1949年的水平设定为100[xiv]。

So, despite the inherent measurement problems, the data are clear: First, the labor share was stable from 1950 to at least near the end of the 1980s. Second, it has fallen precipitously since 2001. While the exact magnitude of the drop may be open to debate, there is no doubt that the downward trend in the labor share since 2001 is unprecedented in the data and, at the time of this writing, shows no signs of abating.

所以如果将这些测量方法所固有的问题放在一边,数据的含义是非常清晰的:首先,从1950年到至少1980年代末,劳动收入占比一直都保持了稳定。第二,从2001年开始,劳动收入占比开始急剧下降。虽然精确的降幅到底是多少仍然有待讨论,但毫无疑问的是,从数据看来,2001年之后的劳动收入占比下降趋势是前所未有的。而直到撰写本文时,这个趋势也丝毫也没有减弱的迹象。

A BIT OF A MIRACLE: 1950-1987

“小小奇迹”:1950-1987

We now take a closer look at the period in which the labor share was stable — roughly from the end of World War II to the late 1980s — by breaking it down by sector. In doing so, we will understand the logic behind the “bit of a miracle” quip. The cutoff date is necessarily 1987, since the industry classification changed in that year. Fortunately, it is also the approximate end date of the stable period for the labor share.

大约从二战结束一直到1980年代末这一时期的美国劳动收入占比一直都很稳定。现在我们来分阶段地仔细审视一下这个时期。这将有助理解这个“小小奇迹”背后的逻辑。我们只能将这一时期的终点选在1987年,因为在1987年,行业的划分标准发生了变化。幸运的是,这一年也恰好几乎是劳动收入占比保持稳定的时代终结的年份。

Since the end of WWII, the U.S. has gone through large structural changes to its sectorial composition. The most significant was the shift from manufacturing to services. In 1950, manufacturing accounted for more than two-thirds of the non-farm business sector. By 1987, manufacturing was just half of the non-farm business sector. Over the same period, services increased from 21 percent to 40 percent of the non-farm business sector.

自从二战结束后,美国经济的产业构成经历了巨大的结构性变化。最明显的变化是经济从制造业向服务业的转型。在1950年,制造业在非农经济中占据的比重超过了三分之二。而到1987年,制造业在非农经济中仅仅占据了一半的比重。同一时期,服务业在非农经济部门中所占的比重则从21%提升到了40%[ix]。

The reader would not be surprised to learn that different sectors use labor and capital in different proportions. In 1950, the manufacturing sector averaged a labor share of 62 percent, with some sub-sectors having even higher labor shares, such as durable goods manufacturing, with a labor share of 77 percent. Services instead relied more on capital and thus had lower labor shares: an average of 48 percent.

对于不同的经济部门中劳动和资本的构成比例不同这一点,相信读者们并不会感到吃惊。在1950年,制造业部门中的平均劳动收入占比是62%,而其中某些子部门的劳动收入占比还要更高,例如在耐用品制造业中,劳动收入占比到了77%[x]。与之相反,服务业则更加依赖于资本,因而其劳动收入占比也更低:平均水平是48%。

Thus, from 1950 to 1987, the sector with a high labor share (manufacturing) was cut in half, while the sector with a low labor share (services) doubled. The aggregate labor share is, naturally, the weighted average across these sectors. Therefore, we would have expected the aggregate labor share to fall. But as we already know, it did not.

也就是说,从1950年到1987年间,劳动收入占比较高的部门(制造业)在经济中的占比下降了接近一半,而劳动收入占比较低的部门(服务业)在经济中的占比则上升了一倍。加总的劳动收入占比很自然地应该等于不同部门劳动收入占比的加权平均值。既然如此,我们应该可以预期,加总的劳动收入占比会下降。但正如我们已经知道的,它并没有下降。

The reason is that, coincidentally with the shift from manufacturing to services, the labor share of the service sector rose sharply, from 48 percent in 1950 to 56 percent in 1987. Education and health services went from labor shares around 50 percent to the highest values in the whole economy, close to 84 percent. In manufacturing, the labor share was substantially more stable, increasing by less than 2 percentage points over the period.

而其中的原因则是在经济从制造业向服务业的转型过程中,服务业中的劳动收入占比却巧合地经历了大幅的上升,从1950年的48%上升到了1987年的56%。教育和医疗服务业中的劳动收入占比从50%左右上升到了整个经济各部门中的最高水平,接近84%[xi]。制造业中的劳动收入占比则持续保持稳定,在整个期间内上升了不到2%。

And this is the “bit of a miracle” — that the forces affecting the labor share across and within sectors just happened to cancel each other out over a period of almost half a century.

而这就是所谓的“小小奇迹”——在接近半个世纪的时间内,部门间和部门内影响劳动收入占比的各种力量恰恰抵消了各自的影响。

A BIT OF A MIRACLE NO MORE: 1987-2011

“小小奇迹”不再:1987-2011

I start by repeating the previous exercise, now over the period 1987 to 2011. As it had from 1950 to 1987, the manufacturing sector kept losing ground to the service sector, albeit at a slower rate.

下面我首先会采取和之前相同的方法来分析美国经济的劳动收入占比,只是将时间段换成1987年-2011年。和1950年-1987年间一样,尽管速度有所下降,但制造业部门在经济中的占比仍然持续被服务业部门所抢占。

By 2011, services accounted for more than two-thirds of U.S. economic output and an even larger fraction of total employment. However, the differences in the labor share between the two sectors were much smaller by the early 1990s, and thus the shift from manufacturing to services had only small downward effects on the overall labor share.

到2011年,服务业在美国经济总产出中所占的比重已经超过了三分之二,而在总就业中的占比甚至更高。然而这两个部门之间劳动收入占比的差异相比1990年代初却缩小了不少,因此,经济从制造业向服务业的转型对总体劳动收入占比仅仅会造成很小的下行作用。

We readily find out which part of the economy is behind the decline of the labor share once we look at the change in the labor share within manufacturing, which dropped almost 10 percentage points. Virtually all the major manufacturing sub-sectors saw their labor shares fall; for non-durable goods manufacturing it dropped from 62 percent to 40 percent. The labor share within the service sector kept increasing, as it had before 1987, but very modestly, only enough to cancel the downward pressure from the shift across sectors. Indeed, had the labor share of income in manufacturing stayed constant, the overall labor share would have barely budged.

只要看看在制造业中劳动收入占比的变化,我们就能很容易地发现经济中的哪一部分是造成劳动收入占比下降的主因。在制造业中,劳动收入占比下降了接近10个百分点。基本上所有主要的制造业子部门都经历了劳动收入占比的下降。在非耐用品制造业中,劳动收入占比从62%下降到了40%。而服务业部门的劳动收入占比相对1987年之前的水平仍然保持了增长,但是增幅非常缓慢,仅仅足够抵消掉由经济从制造业向服务业转型所产生的下行压力。的确,假如制造业中的劳动收入占比能够保持不变,整体经济中的劳动收入占比就几乎不会下降。

Note that in one sense, the bit of a miracle actually continued from 1987 onward: As manufacturing continued to shrink, decreasing the share of income accruing to labor, services picked up the slack by increasing their share of income accruing to labor, albeit more modestly than before. What ended the “miracle” was the precipitous decline in the labor share within manufacturing.

从这个意义上说,“小小奇迹”实际上在1987年之后也得到了延续:制造业在整体经济中占比的持续收缩减少了总收入中劳动收入的比例,而服务业则在一定程度上通过提升部门内的劳动收入占比收拾了残局,虽然提升的速度相比之前已经减缓了许多。终结“奇迹”的实际上是制造业内部劳动收入占比的急剧下降。

Wages and productivity

工资与劳动生产率

It is worth investigating a bit further what determinants are behind the fall in the labor share within manufacturing, since it played such an important role in the decline of the overall labor share. To this end, note that the change in the labor share in a particular sector is linked to the joint evolution of wages and labor productivity.

由于制造业内部的劳动收入占比下降在整体劳动收入占比的下降中发挥了如此重要的作用,更深入地研究其中的决定因素就显得很有价值了。从这个意义上说,我们需要注意到,某个特定部门内的劳动收入占比是与工资和劳动生产率的联合演化联系在一起的。

Consider a machine operator working in a factory for one hour to produce goods that will have a gross value to the factory owner of $100. If he is paid $60 per hour, labor’s share is approximately 60 percent. For the labor share to change, there are only two possibilities: Either the value of the goods produced must change or the hourly wage must. Conversely, for the labor share to stay constant, the value of the goods and the hourly wage have to move in unison.

假如一名机器操作员在工厂中工作一小时能够生产出对于工厂主而言价值100美元的产品,如果他的时薪是60美元,那么劳动收入占比就大约是60%。一旦劳动收入占比发生变化,仅仅有两种可能的情况:要么是产出的价值发生了变化,要么是操作员的时薪发生了变化。反过来说,如果劳动收入占比保持不变,产出的价值和操作员的时薪就必须总是等比例变化[xii]。

So which one — productivity or wages — brought down the labor share in manufacturing? Fortunately, we do have reliable data on output, wage rates, and hours worked in manufacturing. Figure 4 displays the evolution of labor productivity (that is, output per hour) and wage rates from 1950 onward. Both series are set such that their value in 1949 equals 100.

那么在生产率和工资水平中,究竟是哪一项将制造业中的劳动收入占比拖了下来呢?幸运的是,我们拥有制造业中关于产出,单位时间工资和工作时长的可靠数据。图4显示了自1950年以来劳动生产率(也就是每小时产出)和单位时间工资的演化过程[xiii]。两条曲线都将1949年的水平设定为100[xiv]。

Once again we see two clearly separate periods. Until the early 1980s, labor productivity and wages grew at a very similar rate — if anything, the wage rate out-paced productivity, which, as described earlier, implies that the labor share in manufacturing inched up. By mid-1985, labor productivity took off, while wage growth was very sluggish. Since then, the gap between productivity and wages has kept growing, depressing the labor share.

我们又一次地看到了两个被明显分隔开的时期。直到上世纪80年代早期,劳动生产率和工资都一直在以很接近的速度增长——如果有不同的话,也是工资的增长速度超过了劳动生产率。按照之前的描述,这意味着制造业中的劳动收入占比提高了。到上世纪80年代中期,劳动生产率开始突飞猛进,而工资的增长则变得非常缓慢。从那以后,劳动生产率和工资之间的差距就开始持续扩大,从而不断压低劳动收入占比。

Because an index is used to scale both series, it is a tad difficult to grasp from the figure whether labor productivity accelerated or wage rates stagnated from the 1980s onward. The answer is both things happened. In the 1980s, productivity grew at about its long-term trend rate, but wages were virtually flat, growing less than half a percentage point a year on average over the decade. Wage growth recovered in the 1990s, but productivity actually took off, further increasing the gap. Overall, though, it appears that the fall in the labor share is explained mainly by the sluggish growth of wages rather than above-trend labor productivity.

由于我们使用同一个坐标来衡量两条曲线的变化,想要从图中分辨出1980年后究竟是劳动生产率的增长加速了还是单位时间工资的增长停滞了似乎有些困难。答案是两件事情都发生了。在1980年代,劳动生产率的增长速度基本上等于它的长期平均增长率,但是工资增长则相当平缓,这十年中的年均增长率不到0.5%。工资的增长在1990年代有所恢复,但是生产率的增长则突飞猛进,让两者间的差距越来越大。但是整体看来,劳动收入占比的下降更为主要的原因还是缓慢的工资增长速度,而不是增长的劳动生产率。

CONCURRENT PHENOMENA

一些并发的现象

What is the ultimate cause behind the decline of the labor share in the U.S.? The honest answer is that economists have several hypotheses but no definite answer yet. Rather than go over the sometimes-intricate theories behind these hypotheses, I will discuss the main observation or phenomenon anchoring each one.

美国劳动收入占比下降背后的终极原因到底是什么?诚实的回答是,经济学家们目前只是提出了一些假说,但还没有得到确定的答案[xv]。在本文中,我并不准备把这些假说背后的那些有时看起来错综复杂的理论复述一遍,而将讨论与每个假说相关的主要观察结果或现象。

Capital deepening

资本深化

This is by far the most popular hypothesis: Workers have been replaced by equipment and software. Who has not seen footage of robots working an auto assembly line? Older readers may remember when live tellers and not ATMs dispensed cash at banks. Software is now capable of piloting planes and, even more amazingly, doing our taxes!

这是至今为止最流行的假说:工人正在不断地被设备和软件所替代。今天谁还没有见过机器人在汽车流水线上的身影呢?年纪大一些的读者们可能还记得,在过去银行是使用出纳员而不是ATM机来分发现金的。当时的软件还不具备为飞机导航的能力,而更令今人惊讶的是,它们甚至还无法计算我们的税单!

There is more behind this hypothesis than anecdotes. Loukas Karabarbounis and Brent Neiman document a fall in equipment prices. Lawrence Summers proposes that capital should be viewed as at least a partial substitute for labor — more and more so as technology develops. In both models, the idea is similar: Better or cheaper equipment replaces workers and redistributes income from labor to capital. The result is that production becomes more intensive in capital, which is why these theories are often referred to as capital deepening.

这个假说背后有着远比这些旧日轶闻深刻得多的内容。Loukas Karabarbounis和Brent Neiman证明了设备价格的下降趋势。Lawrance Summers则提出,资本至少应该被看作劳动力的一种部分替代——而随着技术的发展,替代的程度也越来越高。在这两个模型中,观点是相似的:更好或者更便宜的设备替代了工人的劳动,并且将之前属于劳动的一部分收入重新分配给了资本。结果就是生产过程的资本密集程度越来越高,这也是这些理论通常被人们称为“资本深化”的原因。

It is important to understand that the capital deepening mechanism must operate at the level of the overall economy. So, when we see a robot replace, say, five workers, we need to remember that the production of the robot itself involved workers, so we are swapping auto assemblers with robot assemblers. It is, of course, still possible that the robot tilts income toward capital, but it is not a foregone conclusion.

重要的是,我们必须懂得资本深化机制只有在整体经济的尺度上才能发挥作用。所以当我们看到一个机器人替代了5名工人时,我们应该记住,机器人的生产本身也需要工人,所以我们只是把汽车装配工换成了机器人装配工而已。当然,机器人的确很有可能会让收入的天平向资本倾斜,但这并非已成定局。

The main challenge to capital deepening is that if a sector is substituting robots for workers to save money or improve the quality of the good being produced, the remaining workers should therefore become more productive and, overall, the sector should be expanding. In other words, capital deepening can reduce the labor share of income, but it does so by making labor productivity accelerate rather than making wages stagnate. As we saw earlier, this does not fit the actual picture of the manufacturing sector at all.

对资本深化理论的主要挑战是,如果某个部门通过使用机器人代替工人来节省成本或者提高所生产的产品质量,那么剩下的工人的生产效率就应该变得更高,而在整体上,这个部门应该会在扩张之中。换句话说,资本深化会降低劳动在总收入中所占的比例,但这是通过让劳动生产率获得提升来完成的,而不是让工资的增长停滞。就像我们之前所看到的,这与制造业所呈现的实际图景完全不相符[xvi]。

Income inequality

收入不平等

The increase in income inequality in the U.S. has lately received a lot of attention. The decline of the labor share is a force toward income inequality because capital is more concentrated across households than labor is.

最近,美国收入不平等的加剧获得了大量的关注。劳动收入占比下降显然是一种加剧收入不平等的力量,因为相比劳动力,资本在家庭间的分布集中度显然更高[xvii]。

It should be noted, though, that the main driver of the increase in income inequality is not capital income but rather wages themselves, particularly at the very top of the pay ladder. As Elsby and his coauthors document, the increase in top wages has actually sustained the labor share. In other words, the decline in the labor share actually understates the increase in income inequality.

但值得一提的是,收入不平等加剧的主要驱动力并不是资本收入,而是工资收入本身,尤其是在工资收入阶梯的顶端[xviii]。正如Elsby和他的合作者们所证明的,顶端工资的增长实际上会起到维持劳动收入占比的作用。换句话说,劳动收入占比的下降实际上还低估了收入不平等程度的加剧。

An interesting question is whether whatever is driving up inequality is also driving down the labor share. Several economists have proposed that technological change is skill biased — that is, it augments productivity more for highly skilled workers than for low-skilled workers. Combined with the idea that capital helps highly skilled workers be more productive but makes unskilled workers redundant, skill bias can explain both the increase in wage inequality and the decline in the labor share.

一个有趣的问题是,任何加剧收入不平等程度的因素是否也同样会降低劳动收入占比呢?一些经济学家提出,技术进步对于工人技能的影响是有偏的——也就是说,相对于低技能的工人,技术进步会更大地提升那些高技能工人的生产力。与之前得出的资本在帮助高技能工人提高生产力同时,让低技能工人变得冗余的观点相结合,“技能偏好”能够同时解释工资收入不平等程度的加剧和劳动收入占比的降低[xix]。

Let us return once more to the car manufacturer example. The robot may be replacing five unskilled workers but may require a qualified operator. The demand for unskilled workers falls, and so do their wages; but the demand for qualified operators increases, and so do their wages. So it is possible to have an increase in wage inequality while factories undergo capital deepening.

让我们再次回到汽车制造商的例子。机器人可能会替代掉5名不熟练的工人,但同时却会需要一名合格的操作员。对不熟练工人的需求下降了,他们的工资收入也会同时下降;但是对合格的操作员的需求和他们的工资水平则会同步提升。所以随着工厂经历资本深化的过程,工资收入的不平等程度也很可能会加剧。

Globalization.

全球化

Another popular hypothesis links the fall in the labor share with the advent of international trade liberalization. There is no question that there has been a substantial increase in trade by U.S. firms in the past few decades. In particular, firms have shifted parts of their production processes to foreign countries to take advantage of cheaper inputs — which, from the perspective of a country like the U.S. that has more capital than other countries, means cheap labor. Industries that are more intensive in labor, such as manufacturing, will be more likely to outsource their production processes abroad, and thus the remaining factories are likely to be the ones that rely more on capital.

另一个流行的假说将劳动收入占比的下降与国际贸易自由化的出现联系在了一起。毫无疑问,在过去的几十年中,美国公司所进行的国际贸易经历了非常显著的增长。尤其值得一提的是,许多美国公司都将它们的一部分生产流程转移到了国外以利用更加便宜的生产要素——对于美国这样一个比他国拥有更多资本的国家来说,也就是劳动力。劳动力更加密集的那些行业,例如制造业,将更有可能将生产流程外包到国外,而那些留在国内的工厂则更可能属于那些对资本依赖程度较高的行业。

Surprisingly, there is not a lot of evidence to support this view. The main challenge to the hypothesis is that U.S. exports and imports are very similar in their factor composition. That is, were trade driving down the labor share, we would observe the U.S. importing goods that use a lot of labor and exporting goods that use a lot of capital. Instead, most international trade involves exchanging goods that are very similar, such as cars.

令人吃惊的是,并没有多少证据能够支持这个观点。这一假说所面临的主要挑战是,美国的进口和出口在要素构成上其实非常相似。也就是说,如果说国际贸易降低了美国的劳动收入占比,那么我们会观察到美国所进口的产品的生产要素中包含大量的劳动,而出口产品的生产要素中则包含大量的资本。但实际上,大多数的国际贸易中所交换的产品都非常相似,例如汽车[xx]。

Another prediction of the globalization theory is that countries the U.S. exports to should see their labor shares increase and — as noted in the accompanying discussion, it appears that the decline in the labor share is a global phenomenon.

支持全球化降低了美国劳动收入占比的理论所作出的另一项预测是,那些从美国进口多于向美国出口的国家的劳动收入占比应该会上升——而我们在之前的讨论中已经提到过,劳动收入占比下降似乎是一个全球性的现象。

Some studies, though, do support this hypothesis. Elsby and his coauthors find some evidence that the labor share fell more in sectors that were more exposed to imports. There is a large body of literature on the impact of trade on wage inequality that only recently has started to consider the impact on the labor share.

事实上,也的确有一些研究支持这个假说。Elsby和他的合作者们发现了一些证据证明在那些受进口冲击更强的行业内,劳动收入占比的确下降得更厉害。已经有大量的文献研究国际贸易对于工资收入不平等的影响,而直到最近,人们才开始考虑它对于劳动收入占比的影响[xxi]。

CONCLUSIONS

结论

Despite several measurement issues and alternative definitions associated with the labor share, the message is quite clear: The 2000s witnessed an unprecedented drop in the labor share of income. Exploring the early period, we saw that the U.S. economy had been able to accommodate the surplus workers from manufacturing only until the late 1980s.

除了一些测量方法上的问题,以及与劳动收入占比相关的一些不同定义之外,我们所获得的信号是非常清晰的:21世纪的前十年见证了美国劳动收入占比的一场史无前例的急剧下降。通过对更早的时期进行研究,我们发现直到1980年代末期,美国一直都能够容纳制造业中多余的劳动力。

We also saw that the stagnation of wages, rather than accelerated labor productivity, has been behind the drop in the labor share from 2000 onward. The review of possible hypotheses behind the decline in the U.S. labor share was, admittedly, quite inconclusive: Economists do not yet have a full grasp of the underlying determinants.

我们还发现,工资增长的停滞,而不是劳动力产出的提升,才是2000年之后劳动收入占比下降的主要原因。需要承认的是,对于一些可能解释美国劳动收入占比下降的假说的回顾并没有得出什么明确的结论:经济学家们仍然没能完整地把握这一现象背后的那些潜在因素。

Once again we see two clearly separate periods. Until the early 1980s, labor productivity and wages grew at a very similar rate — if anything, the wage rate out-paced productivity, which, as described earlier, implies that the labor share in manufacturing inched up. By mid-1985, labor productivity took off, while wage growth was very sluggish. Since then, the gap between productivity and wages has kept growing, depressing the labor share.

我们又一次地看到了两个被明显分隔开的时期。直到上世纪80年代早期,劳动生产率和工资都一直在以很接近的速度增长——如果有不同的话,也是工资的增长速度超过了劳动生产率。按照之前的描述,这意味着制造业中的劳动收入占比提高了。到上世纪80年代中期,劳动生产率开始突飞猛进,而工资的增长则变得非常缓慢。从那以后,劳动生产率和工资之间的差距就开始持续扩大,从而不断压低劳动收入占比。

Because an index is used to scale both series, it is a tad difficult to grasp from the figure whether labor productivity accelerated or wage rates stagnated from the 1980s onward. The answer is both things happened. In the 1980s, productivity grew at about its long-term trend rate, but wages were virtually flat, growing less than half a percentage point a year on average over the decade. Wage growth recovered in the 1990s, but productivity actually took off, further increasing the gap. Overall, though, it appears that the fall in the labor share is explained mainly by the sluggish growth of wages rather than above-trend labor productivity.

由于我们使用同一个坐标来衡量两条曲线的变化,想要从图中分辨出1980年后究竟是劳动生产率的增长加速了还是单位时间工资的增长停滞了似乎有些困难。答案是两件事情都发生了。在1980年代,劳动生产率的增长速度基本上等于它的长期平均增长率,但是工资增长则相当平缓,这十年中的年均增长率不到0.5%。工资的增长在1990年代有所恢复,但是生产率的增长则突飞猛进,让两者间的差距越来越大。但是整体看来,劳动收入占比的下降更为主要的原因还是缓慢的工资增长速度,而不是增长的劳动生产率。

CONCURRENT PHENOMENA

一些并发的现象

What is the ultimate cause behind the decline of the labor share in the U.S.? The honest answer is that economists have several hypotheses but no definite answer yet. Rather than go over the sometimes-intricate theories behind these hypotheses, I will discuss the main observation or phenomenon anchoring each one.

美国劳动收入占比下降背后的终极原因到底是什么?诚实的回答是,经济学家们目前只是提出了一些假说,但还没有得到确定的答案[xv]。在本文中,我并不准备把这些假说背后的那些有时看起来错综复杂的理论复述一遍,而将讨论与每个假说相关的主要观察结果或现象。

Capital deepening

资本深化

This is by far the most popular hypothesis: Workers have been replaced by equipment and software. Who has not seen footage of robots working an auto assembly line? Older readers may remember when live tellers and not ATMs dispensed cash at banks. Software is now capable of piloting planes and, even more amazingly, doing our taxes!

这是至今为止最流行的假说:工人正在不断地被设备和软件所替代。今天谁还没有见过机器人在汽车流水线上的身影呢?年纪大一些的读者们可能还记得,在过去银行是使用出纳员而不是ATM机来分发现金的。当时的软件还不具备为飞机导航的能力,而更令今人惊讶的是,它们甚至还无法计算我们的税单!

There is more behind this hypothesis than anecdotes. Loukas Karabarbounis and Brent Neiman document a fall in equipment prices. Lawrence Summers proposes that capital should be viewed as at least a partial substitute for labor — more and more so as technology develops. In both models, the idea is similar: Better or cheaper equipment replaces workers and redistributes income from labor to capital. The result is that production becomes more intensive in capital, which is why these theories are often referred to as capital deepening.

这个假说背后有着远比这些旧日轶闻深刻得多的内容。Loukas Karabarbounis和Brent Neiman证明了设备价格的下降趋势。Lawrance Summers则提出,资本至少应该被看作劳动力的一种部分替代——而随着技术的发展,替代的程度也越来越高。在这两个模型中,观点是相似的:更好或者更便宜的设备替代了工人的劳动,并且将之前属于劳动的一部分收入重新分配给了资本。结果就是生产过程的资本密集程度越来越高,这也是这些理论通常被人们称为“资本深化”的原因。

It is important to understand that the capital deepening mechanism must operate at the level of the overall economy. So, when we see a robot replace, say, five workers, we need to remember that the production of the robot itself involved workers, so we are swapping auto assemblers with robot assemblers. It is, of course, still possible that the robot tilts income toward capital, but it is not a foregone conclusion.

重要的是,我们必须懂得资本深化机制只有在整体经济的尺度上才能发挥作用。所以当我们看到一个机器人替代了5名工人时,我们应该记住,机器人的生产本身也需要工人,所以我们只是把汽车装配工换成了机器人装配工而已。当然,机器人的确很有可能会让收入的天平向资本倾斜,但这并非已成定局。

The main challenge to capital deepening is that if a sector is substituting robots for workers to save money or improve the quality of the good being produced, the remaining workers should therefore become more productive and, overall, the sector should be expanding. In other words, capital deepening can reduce the labor share of income, but it does so by making labor productivity accelerate rather than making wages stagnate. As we saw earlier, this does not fit the actual picture of the manufacturing sector at all.

对资本深化理论的主要挑战是,如果某个部门通过使用机器人代替工人来节省成本或者提高所生产的产品质量,那么剩下的工人的生产效率就应该变得更高,而在整体上,这个部门应该会在扩张之中。换句话说,资本深化会降低劳动在总收入中所占的比例,但这是通过让劳动生产率获得提升来完成的,而不是让工资的增长停滞。就像我们之前所看到的,这与制造业所呈现的实际图景完全不相符[xvi]。

Income inequality

收入不平等

The increase in income inequality in the U.S. has lately received a lot of attention. The decline of the labor share is a force toward income inequality because capital is more concentrated across households than labor is.

最近,美国收入不平等的加剧获得了大量的关注。劳动收入占比下降显然是一种加剧收入不平等的力量,因为相比劳动力,资本在家庭间的分布集中度显然更高[xvii]。

It should be noted, though, that the main driver of the increase in income inequality is not capital income but rather wages themselves, particularly at the very top of the pay ladder. As Elsby and his coauthors document, the increase in top wages has actually sustained the labor share. In other words, the decline in the labor share actually understates the increase in income inequality.

但值得一提的是,收入不平等加剧的主要驱动力并不是资本收入,而是工资收入本身,尤其是在工资收入阶梯的顶端[xviii]。正如Elsby和他的合作者们所证明的,顶端工资的增长实际上会起到维持劳动收入占比的作用。换句话说,劳动收入占比的下降实际上还低估了收入不平等程度的加剧。

An interesting question is whether whatever is driving up inequality is also driving down the labor share. Several economists have proposed that technological change is skill biased — that is, it augments productivity more for highly skilled workers than for low-skilled workers. Combined with the idea that capital helps highly skilled workers be more productive but makes unskilled workers redundant, skill bias can explain both the increase in wage inequality and the decline in the labor share.

一个有趣的问题是,任何加剧收入不平等程度的因素是否也同样会降低劳动收入占比呢?一些经济学家提出,技术进步对于工人技能的影响是有偏的——也就是说,相对于低技能的工人,技术进步会更大地提升那些高技能工人的生产力。与之前得出的资本在帮助高技能工人提高生产力同时,让低技能工人变得冗余的观点相结合,“技能偏好”能够同时解释工资收入不平等程度的加剧和劳动收入占比的降低[xix]。

Let us return once more to the car manufacturer example. The robot may be replacing five unskilled workers but may require a qualified operator. The demand for unskilled workers falls, and so do their wages; but the demand for qualified operators increases, and so do their wages. So it is possible to have an increase in wage inequality while factories undergo capital deepening.

让我们再次回到汽车制造商的例子。机器人可能会替代掉5名不熟练的工人,但同时却会需要一名合格的操作员。对不熟练工人的需求下降了,他们的工资收入也会同时下降;但是对合格的操作员的需求和他们的工资水平则会同步提升。所以随着工厂经历资本深化的过程,工资收入的不平等程度也很可能会加剧。

Globalization.

全球化

Another popular hypothesis links the fall in the labor share with the advent of international trade liberalization. There is no question that there has been a substantial increase in trade by U.S. firms in the past few decades. In particular, firms have shifted parts of their production processes to foreign countries to take advantage of cheaper inputs — which, from the perspective of a country like the U.S. that has more capital than other countries, means cheap labor. Industries that are more intensive in labor, such as manufacturing, will be more likely to outsource their production processes abroad, and thus the remaining factories are likely to be the ones that rely more on capital.

另一个流行的假说将劳动收入占比的下降与国际贸易自由化的出现联系在了一起。毫无疑问,在过去的几十年中,美国公司所进行的国际贸易经历了非常显著的增长。尤其值得一提的是,许多美国公司都将它们的一部分生产流程转移到了国外以利用更加便宜的生产要素——对于美国这样一个比他国拥有更多资本的国家来说,也就是劳动力。劳动力更加密集的那些行业,例如制造业,将更有可能将生产流程外包到国外,而那些留在国内的工厂则更可能属于那些对资本依赖程度较高的行业。

Surprisingly, there is not a lot of evidence to support this view. The main challenge to the hypothesis is that U.S. exports and imports are very similar in their factor composition. That is, were trade driving down the labor share, we would observe the U.S. importing goods that use a lot of labor and exporting goods that use a lot of capital. Instead, most international trade involves exchanging goods that are very similar, such as cars.

令人吃惊的是,并没有多少证据能够支持这个观点。这一假说所面临的主要挑战是,美国的进口和出口在要素构成上其实非常相似。也就是说,如果说国际贸易降低了美国的劳动收入占比,那么我们会观察到美国所进口的产品的生产要素中包含大量的劳动,而出口产品的生产要素中则包含大量的资本。但实际上,大多数的国际贸易中所交换的产品都非常相似,例如汽车[xx]。

Another prediction of the globalization theory is that countries the U.S. exports to should see their labor shares increase and — as noted in the accompanying discussion, it appears that the decline in the labor share is a global phenomenon.

支持全球化降低了美国劳动收入占比的理论所作出的另一项预测是,那些从美国进口多于向美国出口的国家的劳动收入占比应该会上升——而我们在之前的讨论中已经提到过,劳动收入占比下降似乎是一个全球性的现象。

Some studies, though, do support this hypothesis. Elsby and his coauthors find some evidence that the labor share fell more in sectors that were more exposed to imports. There is a large body of literature on the impact of trade on wage inequality that only recently has started to consider the impact on the labor share.

事实上,也的确有一些研究支持这个假说。Elsby和他的合作者们发现了一些证据证明在那些受进口冲击更强的行业内,劳动收入占比的确下降得更厉害。已经有大量的文献研究国际贸易对于工资收入不平等的影响,而直到最近,人们才开始考虑它对于劳动收入占比的影响[xxi]。

CONCLUSIONS

结论

Despite several measurement issues and alternative definitions associated with the labor share, the message is quite clear: The 2000s witnessed an unprecedented drop in the labor share of income. Exploring the early period, we saw that the U.S. economy had been able to accommodate the surplus workers from manufacturing only until the late 1980s.

除了一些测量方法上的问题,以及与劳动收入占比相关的一些不同定义之外,我们所获得的信号是非常清晰的:21世纪的前十年见证了美国劳动收入占比的一场史无前例的急剧下降。通过对更早的时期进行研究,我们发现直到1980年代末期,美国一直都能够容纳制造业中多余的劳动力。

We also saw that the stagnation of wages, rather than accelerated labor productivity, has been behind the drop in the labor share from 2000 onward. The review of possible hypotheses behind the decline in the U.S. labor share was, admittedly, quite inconclusive: Economists do not yet have a full grasp of the underlying determinants.

我们还发现,工资增长的停滞,而不是劳动力产出的提升,才是2000年之后劳动收入占比下降的主要原因。需要承认的是,对于一些可能解释美国劳动收入占比下降的假说的回顾并没有得出什么明确的结论:经济学家们仍然没能完整地把握这一现象背后的那些潜在因素。

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

Where the Middle Class Goes to Die

哪里的中产阶级没活路?

作者:Kevin D. Williamson @ 2014-9-18

译者:Marcel ZHANG(@马赫塞勒张)

校对:史祥莆(@史祥莆),慕白(@李凤阳他说)

来源:National Review,http://www.nationalreview.com/article/388336/where-middle-class-goes-die-kevin-d-williamson

In progressive Manhattan, inequality is maxed out.

在进步主义盛行的曼哈顿,不平等已达到空前程度。

A new report being released today by the Census Bureau finds that Manhattan has the highest level of income inequality in the United States. That is not entirely surprising, though it would also not have been surprising if it had been San Francisco or another progressive fiefdom.

美国人口调查局(Census (more...)

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

The Middle-Class Squeeze

夹缝中的中产阶级

编辑:Jennifer Erickson @ 2014-9-24

译者:松旭斋天胜(@松旭斋天胜)

校对:安德(@ HuZhenbo)、带菜刀的诗人(@带菜刀的诗人)

制图:amen(@治愈系历史)

来源:美国进步中心(Center for American Progress),https://cdn.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/MiddeClassSqueeze-INTRO.pdf

A Picture of Stagnant Incomes, Rising Costs, and What We Can Do to Strengthen America’s Middle Class

面对收入停滞、生活费高涨的局面,怎么做才能巩固中产阶级

【插图】

America’s middle class is being squeezed by stagnant—and in many cases declining—incomes and rising costs.

美国的中产阶级正被停滞甚至往往是减少的收入和高涨的生活费压得喘不过气。

Why the middle-class squeeze matters

为何需要关注中产阶级重压

The American middle class is in trouble.

美国中产阶级有麻烦了。

The middle-class share of national income has fallen, middle-class wages are stagnant, and the middle class in the United States is no longer the world’s wealthiest.

美国中产阶级收入在国民收入中占比减少,薪资停滞,他们已不再是世界上最富有的中产。

But income is only one side of the story. The cost of being in the middle class—and of maintaining a middle-class standard of living—is rising fast too. For fundamental needs such as child care and health care, costs have risen dramatically over the past few decades, taking up larger shares of family budgets. The reality is that the middle class is being squeezed.

但收入只是问题的一方面。做一个中产阶级、并维持中产阶级生活品质的成本,正在飞涨。过去几十年中,儿童保育和医疗保障等基本生活需求的费用迅速飙升,在家庭预算中比重增大。现实告诉我们,中产阶级正被压得喘不过气来。

As this report will show, for a married couple with two children, the costs of key elements of middle-class security—child care, higher education, health care, housing, and retirement—rose by more than $10,000 in the 12 years from 2000 to 2012, at a time when this family’s income was stagnant.

正如本报告随后将展示的那样,对于一对育有两个子女的夫妇而言,从2000年到2012年的12年间,界定中产阶级的那些关键元素的花费,即儿童保育、高等教育、医疗保障、住房和退休保障的成本,上涨了10000美元,而与此同时,家庭收入却停滞不前。

As sharp as this squeeze can be, the pain does not stop at one family, or even at millions of families. Because of the critical role that middle-class consumers play in creating aggregate demand, the American economy is in trouble when the American middle class is in trouble. And the long-term health of the U.S. economy is at risk if financially squeezed families cannot afford—and smart public policies do not support—developing the next generation of America’s workforce. It is this workforce that will lead the United States in an increasingly open and competitive global economy.

如此严峻的挤迫并不止于一个家庭,或者甚至是百万个家庭。因为中产阶级消费者在创造总需求中扮演着关键角色,当中产阶级出问题,美国经济也随之陷入麻烦。进一步来说,如果经济承受重压的家庭无法负担培养美国下一代劳动力的费用,公共政策也不提供适时的辅助,那么美国经济的长期发展也将处于危险之中。毕竟,未来是由这一代劳动力在更加开放、竞争也更激烈的全球经济体系中领导美国。

This report provides a snapshot of the American middle class and those struggling to become a part of it. It focuses on six key pillars that can help define security for households: jobs, early childhood programs, higher education, health care, housing, and retirement. Each chapter is both descriptive and prescriptive—detailing both how the middle class is doing and what policies can help it do better.

本报告提供了美国中产阶级和正为之而奋斗的人们的一幅速写。它将重点放在对家庭保障起决定作用的六根重要支柱上:就业、儿童保育、高等教育、医疗保障、住房和退休保障。每一部分都在描述现象之余提供建议,不仅详细阐述中产阶级目前的状况,也详尽分析怎样的政策可帮其改善现状。

Defining the middle class

定义中产阶级

Statistically, when we talk about the middle class, we generally mean the middle three quintiles of American households by income—those making between the 20th and 80th percentiles of the income distribution. In reality, however, being middle class in America is at its core about economic security.

统计学上,当我们讨论中产阶级时,一般是指全美收入水平处于中间60%的家庭,即落在20%到80%区间内的家庭。但实际上,美国中产阶级的核心在于家庭经济保障能力。

As Sen. Tom Harkin (D-IA) wrote in the 2011 report “Saving the American Dream,” “Most of us don’t expect to be rich or famous, but we do expect a living wage and good American benefits for a hard day’s work.”

正如参议员Tom Harkin(民主党,爱荷华州)在其2011年题为《挽救美国梦》的报告中写道:“我们中的大部分不求成为富翁或是出名,但我们都希望每日的辛勤工作可以换来足以负担生活开支的工资和良好的社会福利保障。”

At the Ce(more...)

The importance of the middle class to economic growth 中产阶级对经济增长的重要性 Rising inequality is not simply a question of distribution; it also poses real questions for how our economy operates. The increasing resources available to the wealthiest Americans have created demand for such luxuries as private jets—which creates jobs building those jets—but the declining purchasing power of middle-class Americans means that there is less demand for goods and services more broadly in the economy. 不平等加剧不只是个分配问题,它也是为经济运转方式带来了问题。最富有美国人的财富持续增长催生了私人飞机等奢侈品需求,当然,这创造了更多飞机制造业的职位,但是中产阶级购买力下降意味着商品和服务的总需求减少了。 A recent analysis showed that giving $1 to a low-income household produces three times as much consumption as giving $1 to a high-income household. And it is certainly true that increasing the concentration of wealth means more jobs managing finances and fewer jobs making the goods that middle-class consumers once bought in numbers that drove much of our economic growth. 近期的一项分析显示,低收入家庭收入每增加1美元所产生的消费是高收入家庭的三倍。财富集中意味着更多的理财业务职位【编注:这一断言并无道理,财富集中可能增加也可能减少理财职位,要看集中的结果是增加还是减少了财富规模达到需要理财的程度的人数】,和更少的制造业职位,这些工作曾为所制造的产品曾被中产阶级消费者大量购买,而正是这些消费极大地推动了经济增长。 CAP outlined the economic importance of a strong and growing middle class—and the concerns for our economy from growing inequality—in a 2012 report, “The American Middle Class, Income Inequality, and the Strength of the Economy.” The report details the importance of the middle class to human capital, stable demand, entrepreneurship, and support for institutions. 美国进步中心曾在2012年一份题为《美国中产阶级、收入不均及经济实力》的报告中概述了强大且持续增长的中产阶级对于经济的重要性,也说明了扩大的贫富差距对经济造成的问题。该份报告详尽分析了中产阶级对人力资本、稳定的需求、创业的重要性,以及对现行社会制度的支持。【编注:此处institutions含义不明,可能是指制度,也可能是指组织机构】Squeeze part II: A snapshot of rising costs 重压之第二部分:成本上升情况速览 While real incomes have been stagnant or declining in recent years, the other side of the story is the increase in the costs of various items that define a middle-class standard of living. Not only have families’ costs for things from higher education to health care increased rapidly relative to overall consumer inflation, but these costs are also consuming a growing share of family budgets, leaving less and less room for discretionary spending and saving. 近年来实际收入停滞甚至减少的同时,定义中产阶级生活标准的各元素成本却在增长。在家庭支出中,高等教育和医疗保障等项的支出不仅相对消费者物价指数急速增长,它们在家庭预算中比重也在扩大,给自由消费和存款留下的空间越来越少。 When looking at the changes in consumer price indices for core elements of middle-class security, it is painfully easy to see the squeeze in action; prices for many cornerstones of middle-class security have risen dramatically at the same time that real incomes have fallen. 令人心痛的是,在一份与中产阶级经济保障能力相关元素的价格指数变动图表中,可以非常直观地看到压力的存在。对中产阶级经济保障能力至关重要的各项物价飙升,但与此同时,实际收入却在减少。 【插图】 As stark as the data appear when comparing stagnant or falling incomes to rising prices, they are even worse than the Consumer Price Index above might suggest. 虽然停滞或减少的收入和飞升的物价在数据上已十分明显,但实际情况比上图中消费者物价指数所显示的更糟糕。 Let’s consider what has happened to the finances of a typical middle-class family since 2000. 让我们来看看对于一个普通中产阶级家庭来说,2000年以来都有哪些变化。 The median family saw its income fall by 8 percent between 2000 and 2012. Even when we look at just married couples with two children—a type of family that tends to have higher incomes—median income was virtually frozen between 2000 and 2012. 处于中间的家庭在2000到2012年间收入降低了8%。即便我们只把目光放在通常有更高收入的育有两个子女的夫妇上,处于中间的家庭收入在2000到2012年间也仅是持平。 At the same time, this type of family also faced a severe middle-class squeeze as the costs of key elements of security rose dramatically, including child care costs—which grew by 37 percent—and health care costs—both employee premiums and out-of-pocket costs—which grew by 85 percent. 与此同时,这一类家庭也面临着巨大压力:中产保障关键元素的价格急剧升高,儿童保育费用上涨了37%,医疗保障(包括就业医保和自费医疗)费用上涨了85%。 In fact, investing in the basic pillars of middle-class security—child care, housing, and health care, as well as setting aside modest savings for retirement and college—cost an alarming $10,600 more in 2012 than it did in 2000. 事实上,2000到2012年,花费在中产保障关键元素(儿童保育、住房、医疗保障以及为退休和大学存款)上的费用上涨了令人震惊的10,600美元。 Put another way, in 12 years, this household’s income was stagnant—rising by less than 1 percent—while basic pillars of middle-class security rose by more than 30 percent. As the cost of basic elements of middle-class security rose, the money available for everything else—from groceries to clothing to emergency savings—fell by $5,500. 换句话说,12年间,家庭收入没变,或仅提高不到1%,而花费在中产保障上的钱却多了30%。随着各项基本元素的成本上涨,留给其他花销的钱——比如食品杂货、衣服和应急存款等,减少了5500美元。 And while for the purposes of this example we have assumed this household kept retirement savings constant, data about worryingly low savings confirm that for millions of families, their retirement funds are bearing much of the pain of the squeeze. 然而,虽然我们在上述例子中假定该家庭每年留给退休保障的钱维持不变,但令人担忧的低储蓄数据却表明,对于数以百万计的家庭而言,退休保障承受着大部分压力。 【插图】 注:因四舍五入,数据可能略有偏差。2000年至2012年数据根据现有最准确数据估算。详见本系列报告的方法论部分。 来源:见系列报告的方法论部分。 The data paint a clear picture: The middle class is being squeezed. So it should come as no surprise that in a 2014 Pew Research Center survey, 57 percent of Americans responded that they think their incomes are falling behind the growing cost of living, up from 47 percent in 2006. In fact, the percentage of Americans who identify themselves as middle class has fallen to 44 percent, down from 53 percent in 2008. 数据清晰地描绘出这样的图景:中产阶级正受到重压。2014年皮尤研究中心(Pew Research Center)的一项调查显示,57%的美国人认为他们的收入赶不上生活成本的增长速度,而2006年如此认为的人只占47%。这样的结果在意料之中。事实上,认为自己属于中产阶级的美国人由2008年的53%降低到了如今的44%。 Policies to alleviate the squeeze 减轻重压的政策 Understanding that middle-class families are clearly squeezed—with adverse effects on our entire economy—we must craft policies to alleviate the squeeze. This requires two things: growing incomes and containing costs. 既然已经了解了中产阶级面临的困难和它将对我们整个经济带来的负面影响,我们必须设计出合理的政策减轻他们的压力。这包括两方面:增加收入和限制支出。 Jobs 就业 Given that the majority of middle-class families derive their incomes from jobs—as opposed to investments—improving our lackluster jobs picture is the first task to address the middle-class squeeze. To do this, we need to invest in a dynamic economy powered by skilled workers who operate in an environment that lets them and their businesses compete at home and abroad. 鉴于大部分中产阶级收入来源于就业而非投资,减轻压力的第一步便是改善就业环境。我们需要构建一个由技术劳动者支撑的、充满活力的经济环境,让劳动者和企业无论是在本国还是在国际上都具有竞争力。 Doing so will require myriad policies outlined in depth in CAP’s long-term growth strategy, 300 Million Engines of Growth: A Middle-Out Plan for Jobs, Business, and a Growing Economy. Five areas that would directly help the jobs and income pictures in the shorter term include policies to: 为此,美国进步中心在题为《促进增长的三亿个发动机:中产阶级辐射计划,就业、企业和繁荣经济》的长期发展战略中列举了多项政策。

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

Shocking data on wealth inequality

哗众取宠的财富不平等数据

作者:Scott Sumner @ 2015-5-18

译者:Veidt 校对:小聂

来源:Library of Economics and Liberty,http://econlog.econlib.org/archives/2015/05/shocking_new_da.html

Imagine living in a country where the top 30% of the population had roughly 25 times as much wealth per person as the bottom 30% of the population. That seems pretty unequal, doesn’t it?

设想一下,你生活在这样一个国家,其中最富有的30%人口的个人财富大约是最贫穷的30%的人口的25倍。看起来挺不平等的,不是吗?

Now suppose the same statistics applied, but every person at any given age had exactly the same wealth. All 18 year olds had the same wealth as other members of their cohort, as did all 60 year olds. But 18 year olds had much less wealth than 60 year olds.

现在假设同样的统计结果,并且所有年龄相同的人拥有的财富也相同。所有18岁的人和他们的同龄人拥有一样多的财富,所有60岁的人也都拥有相同的(more...)

Dear Dave, My wife and I have just started getting on track with our money. We have $2,000 in savings, and the only debt we have is our house and two cars. I work in the oil and gas industry and make about $180,000 a year, but things are pretty volatile right now. We're upside down on both vehicles, and we owe $39,000 on one and about $48,000 on the other. Under the circumstances, should we go ahead and build a fully funded emergency fund or work on paying off the cars? Kendall 亲爱的Dave,我和妻子才刚刚开始赚钱。我们有两千美元的储蓄,仅有的债务是我们的房贷和两辆车的车贷。我在油气行业工作,每年的收入大约有18万美元,但现在形势很不稳定。为了买这两辆车我们已经把钱都花光了,在其中一辆车上我们欠了39,000美元,另一辆车则欠了48,000美元。在这种情况下,我们是应该把赚来的钱用于设立一个充足的应急基金呢,还是用来偿还两辆汽车的欠款呢?Kendall Dear Kendall, Are you kidding me? Sell the cars, dude! You need to go to Kelly Blue Book's website right now, and find out what your cars are really worth. Then, put them on the market as a private sale. You'll get thousands more selling them that way than you will at a dealership. You'll have to talk to a local credit union or bank for a small loan to cover the difference, plus a little bit more so you guys can get a couple of little beaters to drive for a while. 亲爱的Kendall, 你不是在跟我开玩笑吧?赶快把车都卖了吧,我的朋友! 你现在要做的是去Kelly蓝皮书的网站查一下你的车到底值多少钱,然后以私人销售的名义把它们挂到汽车交易市场上。以这种方式出售,你得到的钱会比你通过汽车经纪商出售多几千美元。你还需要去找一家本地信用合作社或者银行谈谈,借一笔小额贷款来弥补差额,并让你们能够买两辆小“甲壳虫”暂时开一段时间。【译注:此处beaters疑为beatles之讹。】I'm going to go out on a limb and guess there aren't very many similar letters in China. Like the advice columnist "Dave", I have a temperament that makes it easy to save. But as a libertarian I favor allowing people like Kendall to spend their money when and how they wish. 这里我想斗胆猜测一下,中国应该不会有太多类似的读者来信。和上面那位建议专栏的作者Dave一样,我在性格上倾向于储蓄。但是作为一名自由意志主义者,我倾向于允许Kendall这样的人按自己的意愿去决定何时、如何花自己的钱。 The only qualification is that I think people should be forced to save enough to cover the things that society would otherwise have to pay (basic retirement, medical, etc.) 我认为唯一合理的限制是,假如因为人们因自己的储蓄不足,而需要整个社会来付出代价时,强制性储蓄才是必须的(例如基本的退休工资,医疗保障等)。 If we believe that people should be free to choose when to spend their wealth, we will end up with far more wealth inequality than if we try to force everyone to consume the "right amount" of each year's income. But I don't see how that sort of wealth inequality could be considered a problem. 如果我们相信人们拥有选择何时花掉自己所拥有财富的自由,那么相比强制所有人都花掉每年收入中“正确比例”的钱,最终的财富不平等程度会高得多。但我完全不觉得这种原因导致的财富不平等会是个问题。 Inevitably some will misconstrue what I am saying here. Just to be clear, even accounting for all the factors I mentioned (age, saving preferences, etc) there is still lots more inequality due to big differences in lifetime earnings (or inherited wealth.) So this post is not trying to suggest that inequality is not a problem. 难免有人会误解我的意思,所以我要澄清一下,即便考虑了上面提到的所有这些因素(年龄、储蓄偏好等)之后,由人们生命周期中巨大的收入差异(或是财产继承上的差异)所造成的不平等仍然是巨大的。这篇文章并不是想说不平等不是个问题。 Rather I'm suggesting that if inequality is a problem, we would not be able to know that from the wealth inequality data that is presented in the media. And that's because even if wealth inequality were not a problem at all, the actual inequality of wealth would look shocking large, with 100 to 1 disparities easily accounted for by nothing more than differences in age and saving propensities. 实际上我更想表达的是,假如不平等的确是一个问题,我们并不能从媒体上出现的那些有关财富不平等的数据里得知这一点。因为即使在那些财富不平等根本不算个问题的情况下,实际数据上的财富不平等程度看起来也会很惊人,仅仅是年龄和储蓄偏好上的一些差异就能轻易地造成100比1这样的差距。 The only data that truly gets at the inequality question is consumption inequality, which is very rarely discussed in the media. 对于不平等问题,唯一切中要害的数据,其实是消费的不平等,但有关后者却极少在媒体上被讨论。 (编辑:辉格@whigzhou) *注:本译文未经原作者授权,本站对原文不持有也不主张任何权利,如果你恰好对原文拥有权益并希望我们移除相关内容,请私信联系,我们会立即作出响应。

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——