BOOK REVIEW: ALBION’S SEED

书评:《阿尔比恩的的种子》

作者:SCOTT ALEXANDER @ 2016-04-27

译者:Tankman

校对:沈沉(@沈沉-Henrysheen)

来源:

http://slatestarcodex.com/2016/04/27/book-review-albions-seed/

I.

Albion’s Seed by David Fischer is a history professor’s nine-hundred-page treatise on patterns of early immigration to the Eastern United States. It’s not light reading and not the sort of thing I would normally pick up. I read it anyway on the advice of people who kept telling me it explains everything about America. And it sort of does.

《阿尔比恩的种子》是历史学教授David Fischer 所作的九百页专著【

校注:阿尔比恩,英国旧称,据说典出海神之子阿尔比恩在岛上立国的神话】。该书讨论了美国东部地区的早期移民的模式。阅读此书并不轻松,而且一般我也不会挑选这种书来读。但不管如何,我读完了。这是因为有人向我推荐此书,他们不断告诉我它能解释关于美国的一切。而某种程度上,此书做到了这点。

In school, we tend to think of the original American colonists as “Englishmen”, a maximally non-diverse group who form the background for all of the diversity and ethnic conflict to come later. Fischer’s thesis is the opposite. Different parts of the country were settled by very different groups of Englishmen with different regional backgrounds, religions, social classes, and philosophies. The colonization process essentially extracted a single stratum of English society, isolated it from all the others, and then plunked it down on its own somewhere in the Eastern US.

在学校,我们倾向于把初代北美殖民者看作是“英国人”,这是一个最不多元化的群体,并且构成了后来所有的多元性和种族冲突的背景。Fischer的论述则与此相反。这个国家的不同地区被非常不同的英国人群体开拓。这些群体有着不同的地区背景,宗教,社会阶级和哲学。殖民化过程其实是提取了英国社会的某个单一阶层,令其与其他阶层隔绝,而后在美国东部的某个地方打上该群体深深的烙印。

I used to play Alpha Centauri, a computer game about the colonization of its namesake star system. One of the dynamics that made it so interesting was its backstory, where a Puerto Rican survivalist, an African plutocrat, and other colorful characters organized their own colonial expeditions and competed to seize territory and resources. You got to explore not only the settlement of a new world, but the settlement of a new world by societies dominated by extreme founder effects.

我曾玩过电脑游戏《南门二》。这游戏是关于与游戏同名的星系的殖民活动的。游戏如此有趣的一个因素是其故事背景:一个波多黎各生存狂,一个非洲财阀,以及其他有色人种角色组织了他们自己的殖民探险,相互竞争,来占领领土和资源。你能探索的,不单单只是对新世界拓殖,而且是那种受极端奠基者效应支配的社会对新世界的拓殖。

What kind of weird pathologies and wonderful innovations do you get when a group of overly romantic Scottish environmentalists is allowed to develop on its own trajectory free of all non-overly-romantic-Scottish-environmentalist influences? Albion’s Seed argues that this is basically the process that formed several early US states.

当一群过度浪漫的苏格兰环保主义者被允许自由发展,不受其他群体影响时,你能得到什么样怪异的社会失序或是伟大创新呢?《阿尔比恩的种子》认为这基本上是早期美国的某几个州形成的过程。

Fischer describes four of these migrations: the Puritans to New England in the 1620s, the Cavaliers to Virginia in the 1640s, the Quakers to Pennsylvania in the 1670s, and the Borderers to Appalachia in the 1700s.

Fischer描述了这些移民中的四种:在1620年代来到新英格兰地区的清教徒,在1640年代来到弗吉尼亚的“骑士党”,在1670年代来到宾夕法尼亚的贵格会,以及1700年代来到阿巴拉契亚山地的边民【

校注:指英格兰和苏格兰交界地区的人】。

II.

A: The Puritans

A:清教徒

I hear about these people every Thanksgiving, then never think about them again for the next 364 days. They were a Calvinist sect that dissented against the Church of England and followed their own brand of dour, industrious, fun-hating Christianity.

我在每个感恩节都听说过这群人,而后在接下来的364天,就再也没有想起过他们。他们是一个加尔文宗派,对英国国教会持异议,而且遵从他们特有的严厉,勤奋,厌恶享乐的基督教伦理。

Most of them were from East Anglia, the part of England just northeast of London. They came to America partly because they felt persecuted, but mostly because they thought England was full of sin and they were at risk of absorbing the sin by osmosis if they didn’t get away quick and build something better. They really liked “city on a hill” metaphors.

他们中的大多数,来自东英吉利,是位于伦敦东北方向的一个地区。他们来到美国,部分是因为他们感到被迫害,但是大部分原因是他们觉得英国充满了罪恶,如果不尽快离开并且构建更好的生活,他们就面临被罪恶渗透的风险。他们真是非常喜爱“山巅之城”这个比喻。

I knew about the Mayflower, I knew about the black hats and silly shoes, I even knew about

the time Squanto threatened to release a bioweapon buried under Plymouth Rock that would bring about the apocalypse. But I didn’t know that the Puritan migration to America was basically a eugenicist’s wet dream.

我知道五月花,我知道清教徒的黑帽和有些滑稽的皮鞋,我甚至知道印第安领袖Squanto曾威胁释放普利茅斯岩石之下那能够带来末日灾难的生物武器。但是我不知道清教徒移民美国基本上是个优生学的春梦。

Much like eg Unitarians today, the Puritans were a religious group that drew disproportionately from the most educated and education-obsessed parts of the English populace. Literacy among immigrants to Massachusetts was twice as high as the English average, and in an age when the vast majority of Europeans were farmers most immigrants to Massachusetts were skilled craftsmen or scholars. And the Puritan “homeland” of East Anglia was a an unusually intellectual place, with strong influences from Dutch and Continental trade; historian Havelock Ellis finds that it “accounts for a much larger proportion of literary, scientific, and intellectual achievement than any other part of England.”

清教徒这个宗教团体很像今天的唯一神教派,其成员中很多是受过最好教育、最痴迷于教育的英国民众。来到马萨诸塞的移民,其拥有读写能力的比例,是英国平均水平的两倍;在一个大部分欧洲人还是农夫的时代,大部分马萨诸塞的移民是熟练技工或学者。而清教徒在东英吉利的“故土”则是个文教很发达的地方,受到荷兰和大陆贸易的强烈影响;历史学家Havelock Ellis发现,“相比英国的其他任何地区,该地很大程度上以文艺,科学和知识成就著称。”

Furthermore, only the best Puritans were allowed to go to Massachusetts; Fischer writes that “it may have been the only English colony that required some of its immigrants to submit letters of recommendation” and that “those who did not fit in were banished to other colonies and sent back to England”. Puritan “headhunters” went back to England to recruit “godly men” and “honest men” who “must not be of the poorer sort”.

而且,只有最好的清教徒,才能被允许来到马萨诸塞;Fischer写道,“这也许是唯一要求部分移民出具推荐信的英国殖民地”,而且“不适合该地的移民,则被放逐到其他殖民地,或是送回英国。”清教徒“猎头”回到英国去招募“虔敬的人”和“诚实的人”,这些人“绝对不能是阶层较低的那一类”。

INTERESTING PURITAN FACTS:

关于清教徒的一些有趣事实:

1. Sir Harry Vane, who was “briefly governor of Massachusetts at the age of 24”, “was so rigorous in his Puritanism that he believed only the thrice-born to be truly saved”.

Harry Vane先生“在24岁时曾短期担任马萨诸塞殖民地的长官”。“他践行清教徒伦理十分严格,以至于相信只有第三次重生的人才能够得救”。

2. The great seal of the Massachusetts Bay Company “featured an Indian with arms beckoning, and five English words flowing from his mouth: ‘Come over and help us'”

马萨诸塞湾公司的大印上刻着“一个印第安人在招手,从他嘴里喊出五个词:‘来帮助我们’”。

3. Northern New Jersey was settled by Puritans who named their town after the “New Ark Of The Covenant” – modern Newark.

新泽西北部的清教徒开拓者把他们的镇起名为“新约柜”————即如今的纽瓦克

4. Massachusetts clergy were very powerful; Fischer records the story of a traveller asking a man “Are you the parson who serves here?” only to be corrected “I am, sir, the parson who

ruleshere.”

马萨诸塞的牧师有很大权力;Fischer记录了一个故事:一个旅行者问一个男人“您是在此地服侍的牧师吗?”被问者纠正了他的问题,“先生,我是统治此地的牧师。”

5. The Puritans tried to import African slaves, but they all died of the cold.

清教徒试图进口黑奴,但是黑奴全部死于严寒。

6. In 1639, Massachusetts declared a “Day Of Humiliation” to condemn “novelties, oppression, atheism, excesse, superfluity, idleness, contempt of authority, and trouble in other parts to be remembered”.

1639年,马萨诸塞发起了“羞辱日”,以谴责“新潮,压迫,无神论,纵欲,奢侈,懒散,轻视权威以及其他引人注目的麻烦”。

7. The average family size in Waltham, Massachusetts in the 1730s was 9.7 children.

1730年代,在马萨诸塞的Waltham,平均家庭规模是9.7个孩子。

8. Everyone was compelled by law to live in families. Town officials would search the town for single people and, if found, order them to join a family; if they refused, they were sent to jail.

按照法律,每个人都必须生活在家庭中。城镇官员会搜查镇中的单身者,如果发现,则会命令其加入一个家庭;如果单身者拒绝,则会被投入监狱。

9. 98% of adult Puritan men were married, compared to only 73% of adult Englishmen in general. Women were under special pressure to marry, and a Puritan proverb said that “women dying maids lead apes in Hell”.

98%的清教徒成年男子都结了婚,而英国成年男子总体的结婚率为73%。要求妇女结婚的压力特别大,一句清教徒格言说“没结婚的女人死后在地狱里带领着猿猴”。【

译注:这一格言大意是谴责独身主义,但字面意思难考,一说是因为猿猴在当时人看来是没有价值的动物,肉不可吃,也不能做驼兽或者看家。】

10. 90% of Puritan names were taken from the Bible. Some Puritans took pride in their learning by giving their children obscure Biblical names they would expect nobody else to have heard of, like Mahershalalhasbaz. Others chose random Biblical terms that might not have technically been intended as names; “the son of Bostonian Samuel Pond was named Mene Mene Tekel Upharsin Pond”. Still others chose Biblical words completely at random and named their children things like Maybe or Notwithstanding.

90%清教徒的名字都取自圣经。一些清教徒引以为豪的是:用他们料想没人听过的圣经中的生僻词给孩子取名,并以此夸耀自己的学问,以至于他们可以预期人们从来没听过这个名字,比如 Mahershalalhasbaz【

译者注:掳掠速临,抢夺快到。见圣经以赛亚书第八章1节】。另一些则随机取用圣经中的词,有些词技术上说本不是用来做名字的;“Bostonian Samuel Pond的孩子被起名为 Mene Mene Tekel Upharsin Pond”【

译者注:前四个单词作为孩子的名,引自圣经但以理书第五章25节。四个单词都是亚兰文的度量单位,表示神已经数算过巴比伦的岁月,神已称量了巴比伦的道德】。也有些人,完全随机取用圣经中的词,给他们的孩子取名为Maybe或者是Notwithstanding。

11. Puritan parents traditionally would send children away to be raised with other families, and raise those families’ children in turn, in the hopes that the lack of familiarity would make the child behave better.

传统上,清教徒父母把孩子送给别的家庭寄养,作为交换,他们也寄养别人家的孩子,他们希望家中缺失亲情可以让孩子们被管教得更好。

12. In 1692, 25% of women over age 45 in Essex County were accused of witchcraft.

在1692年,Essex郡25%的45岁以上妇女被控为女巫。

13. Massachusetts passed the first law mandating universal public education, which was called The Old Deluder Law in honor of its preamble, which began “It being one chief project of that old deluder, Satan, to keep men from the knowledge of the scriptures…”

马萨诸塞通过了第一部强制普及公共教育的法律,被称为“老说谎者法案”,因为其前言的开头写道:“老牌说谎者撒旦的一个主要活动,就是阻止人们接触到经文的知识……”

14. Massachusetts cuisine was based around “meat and vegetables submerged in plain water and boiled relentlessly without seasonings of any kind”.

马萨诸塞的饮食基本上是“白水炖煮肉和蔬菜,不加任何调料”。

15. Along with the famous scarlet A for adultery, Puritans could be forced to wear a B for blasphemy, C for counterfeiting, D for drunkenness, and so on.

除了著名的表示通奸的红字A,清教徒还因为渎神被强制穿上B(blasphemy),因为造假被穿上C( counterfeiting ),因为醉酒被穿上D( drunkenness ),如此种种。

16. Wasting time in Massachusetts was literally a criminal offense, listed in the law code, and several people were in fact prosecuted for it.

在马萨诸塞,浪费时间是一种犯罪行为,列在法条上,并有几人的确因此被起诉。

17. This wasn’t even the nadir of weird hard-to-enforce Massachusetts laws. Another law just said “If any man shall exceed the bounds of moderation, we shall punish him severely”.

这还不是难以被执行的马萨诸塞法律的极点。另一条法律说:“如果任何人超越了适度的界限,我们将对其进行严惩。”

Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote of Massachusetts Puritanism: “The underlying foundation of life in New England was one of profound, unutterable, and therefore unuttered mehalncholy, which regarded human existence itself as a ghastly risk, and, in the case of the vast majority of human beings, an inconceivable misfortune.”

Harriet Beecher Stowe就马萨诸塞的清教主义写道:“新英格兰生活的基础是一种深刻微妙,无法言说,因此也就未被说破的惆怅,即人类的存在本身就是一种可怖的风险,绝大多数人,其存在是一种不可思议的不幸。”

And indeed, everything was dour, strict, oppressive, and very religious. A typical Massachusetts week would begin in the church, which doubled as the town meeting hall. There were no decorations except a giant staring eye on the pulpit to remind churchgoers that God was watching them.

而且的确,一切都是严厉,严格,压抑并且非常宗教化的。马萨诸塞典型的一周生活开始于教堂,其规模是镇议事厅的两倍。教堂里没有别的装饰,除了牧师讲道台上的一个巨大眼睛,提醒来教堂的人们上帝在看着他们。

Townspeople would stand up before their and declare their shame and misdeeds, sometimes being forced to literally crawl before the other worshippers begging for forgiveness. THen the minister would give two two-hour sermons back to back. The entire affair would take up to six hours, and the church was unheated (for some reason they stored all their gunpowder there, so no one was allowed to light a fire), and this was Massachusetts, and it was colder in those days than it is now, so that during winter some people would literally lose fingers to frostbite (Fischer: “It was a point of honor for the minister never to shorten a sermon merely because his audience was frozen”). Everyone would stand there with their guns (they were legally required to bring guns, in case Indians attacked during the sermon) and hear about how they were going to Hell, all while the giant staring eye looked at them.

在讲道开始前,镇上的人坦白自己的羞耻和劣迹,有时真的是被强迫匍匐在其他敬拜者前,乞求饶恕。然后布道者会开始连续两场两小时长的证道。整个过程可以花掉六小时,而且教堂里没有取暖设施(出于一些原因,人们把所有的火药储存在教堂,所以那里禁止生火),而且这可是马萨诸塞,那时候天气比今天更冷,所以在冬季,有人真的会因为冻疮失去手指。(Fischer:“对布道者来说,从不因听众冻僵而缩短证道是一种荣耀。”)每个人站在那里,带着他们的枪(法律上,他们被要求携带武器,以防印第安人在其听讲道时袭击),听着他们将会怎样下地狱,整个过程,那巨大的眼睛一直盯着他们。

So life as a Puritan was pretty terrible. On the other hand, their society was

impressively well-ordered. Teenage pregnancy rates were the lowest in the Western world and in some areas literally zero. Murder rates were half those in other American colonies.

所以一个清教徒的生活是非常恐怖的。另一方面,他们的社会有着令人印象深刻的良好秩序。未成年人怀孕率曾是西方世界中最低的,在某些地方则实际上为零。谋杀率则只有其他北美殖民地的一半。

There was remarkably low income inequality – “the top 10% of wealthholders held only 20%-30% of taxable property”, compared to 75% today and similar numbers in other 17th-century civilizations. The poor (at least the poor native to a given town) were treated with charity and respect – “in Salem, one man was ordered to be set by the heels in the stocks for being uncharitable to a poor man in distress”.

收入差距很低——“10%最富者只占有可税财产的20%-30%”,对比而言,今天这个比例是75%,17世纪时的其他文明也近似这个数字。穷人(至少是在镇上的本地穷人)受到尊重和接济——“在Salem,一个男人因为不肯接济一位在苦难中的穷人,被罚上脚枷示众”。

Government was conducted through town meetings in which everyone had a say. Women had more equality than in most parts of the world, and domestic abuse was punished brutally. The educational system was top-notch – “by most empirical tests of intellectual eminence, New England led all other parts of British America from the 17th to the early 20th century”.

政府通过镇上的议事会议得以运作,每个人在会上都有发言权。比世界其他地方,妇女享有更多平等,而家庭暴力则会遭到严酷惩罚。教育系统是顶尖的——“从十七世纪到二十世纪早期,在大多数有关智识能力的经验测试中,新英格兰领先所有其他北美的英国殖民地”。

In some ways the Puritans seem to have taken the classic dystopian bargain – give up all freedom and individuality and art, and you can have a perfect society without crime or violence or inequality. Fischer ends each of his chapters with a discussion of how the society thought of liberty, and the Puritans unsurprisingly thought of liberty as “ordered liberty” – the freedom of everything to tend to its correct place and stay there.

某种程度上,清教徒似乎选择了经典的敌托邦方案——放弃一切自由、个体性和艺术,得到一个没有犯罪、暴力和不平等的完美社会。Fischer在每一章的结尾部分都会探讨该社会如何看待自由,而清教徒毫不奇怪地认为自由是“有秩序的自由”——在这种自由下,万物都处于正确的位置,并且保持这种状态。

They thought of it as a freedom from disruption – apparently FDR stole some of his “freedom from fear” stuff from early Puritan documents. They were extremely not in favor of the sort of liberty that meant that, for example, there wouldn’t be laws against wasting time.

That was going too far.

他们认为这是一种免于被扰乱的自由——显然富兰克林·罗斯福从早期清教徒的文档中,偷取了一些创意,用于他的“免于恐惧的自由”的理念。他们非常不喜欢某些类型的自由,比如,没有禁止浪费时间的法律。这种自由实在是过度了。

B: The Cavaliers

B:骑士党

The Massachusetts Puritans fled England in the 1620s partly because the king and nobles were oppressing them. In the 1640s, English Puritans under Oliver Cromwell rebelled, took over the government, and killed the king. The nobles not unreasonably started looking to get the heck out.

马萨诸塞清教徒在1620年代逃离英格兰,部分是因为国王和贵族压迫他们。在1640年代,英国清教徒在奥利弗·克伦威尔的领导下反叛,夺取了政权,处死了国王。贵族在此时开始想要尽快逃离并不是没有原因的。

Virginia had been kind of a wreck ever since most of the original Jamestown settlers had mostly died of disease. Governor William Berkeley, a noble himself, decided the colony could reinvent itself as a destination for refugee nobles, and told them it would do everything possible to help them maintain the position of oppressive supremacy to which they were accustomed. The British nobility was sold. The Cavaliers – the nobles who had fought and lost the English Civil War – fled to Virginia.

自从詹姆斯敦最初一批殖民者中的大部分死于疾病,弗吉尼亚一度沦落得像一片废墟。殖民地长官 William Berkeley自己就是个贵族。他决定殖民地应该转型为一个避难贵族的目的地。他告诉避难的贵族,殖民地将会竭尽全力,帮他们维持其久已习惯的压迫性支配地位。不列颠的贵族地位标价出售。骑士党——在英国内战中顽抗继而失败的贵族——逃至弗吉尼亚。

Historians who cross-checking Virginian immigrant lists against English records find that of Virginians whose opinions on the War were known, 98% were royalists. They were overwhelming Anglican, mostly from agrarian southern England, and all related to each other in the incestuous way of nobility everywhere: “it is difficult to think of any ruling elite that has been more closely interrelated since the Ptolemies”. There were twelve members of Virginia’s royal council; in 1724 “all without exception were related to one another by blood or marriage…as late as 1775, every member of that august body was descended from a councilor who had served in 1660”.

历史学家交叉对比了弗吉尼亚移民的名单和英国的记录,他们发现,对于英国内战,立场可知的弗吉尼亚人当中,98%是保皇党。他们绝大多数都是国教徒,大部分来自英国南部的农业区,互相之间都有贵族间内婚的血缘关系:“很难想到自托勒密王朝以来,统治精英还有比这更近的亲缘关系”。弗吉尼亚皇家议会有十二名成员;在1724年“无一例外的彼此有着血缘或姻亲关系……迟至1775年,这一庄严机构的每个成员都是其1660年委员的后代”。

These aristocrats didn’t want to do their own work, so they brought with them tens of thousands of indentured servants; more than 75% of all Virginian immigrants arrived in this position. Some of these people came willingly on a system where their master paid their passage over and they would be free after a certain number of years; others were sent by the courts as punishments; still others were just plain kidnapped. The gender ratio was 4:1 in favor of men, and there were entire English gangs dedicated to kidnapping women and sending them to Virginia, where they fetched a high price. Needless to say, these people came from a very different stratum than their masters

or the Puritans.

这些贵族不想自己做工,所以他们带来上万的契约仆佣;超过75%的弗吉尼亚移民以这个身份【

编注:即契约仆佣】到来。一些人是自愿而来,主人支付了他们的旅费,他们在服务一些年份后会获得自由;另一些人则被法庭判罚来到这里;还有些人明显是被拐骗的。男女性别比是4:1,存在专门贩卖妇女到弗吉尼亚的英国黑帮,他们从中赚取高价。无需多言,相比于他们的贵族主人或清教徒,这些人来自一个非常不同的阶层。

People who came to Virginia mostly died. They died of malaria, typhoid fever, amoebiasis, and dysentery. Unlike in New England, where Europeans were better adapted to the cold climate than Africans, in Virginia it was Europeans who had the higher disease-related mortality rate. The whites who survived tended to become “sluggish and indolent”, according to the universal report of travellers and chroniclers, although I might be sluggish and indolent too if I had been kidnapped to go work on some rich person’s farm and sluggishness/indolence was an option.

来到弗吉尼亚的人多数都死了。他们死于疟疾,伤寒,阿米巴病,和痢疾。不像在新英格兰,在那里欧洲人比非洲人更好的适应了寒冷气候,在弗吉尼亚,欧洲人有着更高的疾病死亡率。参考旅行者的报告和编年史,幸存下来的白人倾向于变得“低迷和懒惰”,当然,我也许也会变得低迷和懒惰,如果我被诱拐到某个富人的农场做工而且可以选择低迷/懒惰的话。

The Virginians tried their best to oppress white people. Really, they did. The depths to which they sank in trying to oppress white people almost boggle the imagination. There was a rule that if a female indentured servant became pregnant, a few extra years were added on to their indenture, supposedly because they would be working less hard during their pregnancy and child-rearing so it wasn’t fair to the master. Virginian aristocrats would

rape their own female servants, then add a penalty term on to their indenture for becoming pregnant.

弗吉尼亚人竭尽全力的压迫白人。确实,他们干过这种事。他们试图压迫白人的深度,超乎想象。有一条规矩:如果女性契约仆人怀了孕,她们的服务期会被延长几年,大概是因为她们的产出在孕期和抚育期会下降,这就对主人不公平。弗吉尼亚贵族们会强奸自己的女性仆人,而后给她们的服务期加上基于怀孕的惩罚期限。

That is an

impressive level of chutzpah. But despite these efforts, eventually all the white people either died, or became too sluggish to be useful, or worst of all just finished up their indentures and became legally free. The aristocrats started importing black slaves as per the model that had sprung up in the Caribbean, and so the stage was set for the antebellum South we read about in history classes.

这种无耻妄为令人印象深刻。但是虽然有这些努力,最终所有白人不是死了,就是变得太低迷以至于无用,或者最糟糕的是他们结束了服务期限,在法律上变得自由了。贵族开始按照加勒比地区涌现的那种模式引进黑奴,于是我们在历史课上读到的内战前南方的一幕幕已经预备好上演。

INTERESTING CAVALIER FACTS:

关于骑士党的有趣事实:

1. Virginian cavalier speech patterns sound a lot like modern African-American dialects. It doesn’t take much imagination to figure out why, but it’s strange to think of a 17th century British lord speaking what a modern ear would clearly recognize as Ebonics.

弗吉尼亚骑士党的说话腔调听来更像是现代非裔美国人。不用多想就能推测出原因,不过想到17世纪的不列颠贵族讲一口现在听来是黑人英语的腔调,的确很奇怪。

2. Three-quarters of 17th-century Virginian children lost at least one parent before turning 18.

四分之三的17世纪弗吉尼亚孩子在十八岁之前至少丧失父母之一。

3. Cousin marriage was an important custom that helped cement bonds among the Virginian elite, “and many an Anglican lady changed her condition but not her name”.

堂亲结婚是弗吉尼亚精英加固联盟的重要习俗,“很多国教徒女士改变了她们的境遇,但不改变其姓氏”。

4. In Virginia, women were sometimes unironically called “breeders”; English women were sometimes referred to as “She-Britons”.

在弗吉尼亚,并非出于讽刺,妇女有时被称作“育仔员”;英国妇女有时被称作“女不列颠人”。

5. Virginia didn’t really have towns; the Chesapeake Bay was such a giant maze of rivers and estuaries and waterways that there wasn’t much need for land transport hubs. Instead, the unit of settlement was the plantation, which consisted of an aristocratic planter, his wife and family, his servants, his slaves, and a bunch of guests who hung around and mooched off him in accordance with the ancient custom of hospitality.

弗吉尼亚没有真正的城镇;切萨皮克湾是众多河流、河口和水路组成的迷宫,并不需要陆路运输的集散地。相反,殖民的基本单位是种植园,由一位贵族种植园主,他的妻子和家庭,他的仆人,他的奴隶,以及一群借着古已有之的好客传统依附寄生于主人的宾客们组成。

6. Virginian society considered everyone who lived in a plantation home to be a kind of “family”, with the aristocrat both as the literal father and as a sort of abstracted patriarch with complete control over his domain.

弗吉尼亚社会认为每个生活在种植园中的人多少都算是“家庭成员”,而贵族既是真正的父亲,也是控制自己地域的抽象家主。

7. Virginia governor William Berkeley probably would not be described by moderns as ‘strong on education’. He said in a speech that “I thank God there are no free schools nor printing [in Virginia], and I hope we shall not have these for a hundred years, for learning has brought disobedience, and heresy, and sects into the world, and printing has divuldged them, and libels against the best government. God keep us from both!”

按现代观点,弗吉尼亚殖民地长官William Berkeley很可能算不上“重视教育”。他在一次演说中说“我感谢上帝,(在弗吉尼亚)没有免费学校和印刷术,而且我希望我们一百年也不要有这些东西,因为学习给世界带来不服从、异端、和结党,印刷术则传播上述这些,以及对最佳政府的诽谤。上帝让我们远离学校和印刷术。”

8. Virginian recreation mostly revolved around hunting and bloodsports. Great lords hunted deer, lesser gentry hunted foxes, indentured servants had a weird game in which they essentially draw-and-quartered geese, young children “killed and tortured songbirds”, and “at the bottom of this hierarchy of bloody games were male infants who prepared themselves for the larger pleasures of maturity by torturing snakes, maiming frogs, and pulling the wings off butterflies. Thus, every red-blooded male in Virginia was permitted to slaughter some animal or other, and the size of his victim was proportioned to his social rank.”

弗吉尼亚的休闲活动大多涉及打猎和血腥运动。大领主猎鹿,小绅士猎狐,契约仆人玩着奇怪的游戏来肢解鹅,年幼的孩子“杀死和折磨鸣禽”,而“在这一血腥游戏等级体系底部的则是男性幼童,为了长大后享受更大的猎杀愉悦,他们折磨蛇、残害青蛙、扯掉蝴蝶的翅膀。因此,每个热血的弗吉尼亚男性都被允许屠杀这样或那样一些动物,其受害者的尺寸则和他的社会等级成比例。”

9. “In 1747, an Anglican minister named William Kay infuriated the great planter Landon Carter by preaching a sermon against pride. The planter took it personally and sent his [relations] and ordered them to nail up the doors and windows of all the churches in which Kay preached.”

“在1747年,一个叫William Kay的国教会牧师因为一篇反对骄傲的讲道,激怒了大种植园主Landon Carter。种植园主认为这是对其个人的冒犯,派出了他的亲属,命其钉死所有Kay牧师曾讲过道的教堂的门窗。

10. Our word “condescension” comes from a ritual attitude that leading Virginians were supposed to display to their inferiors. Originally condescension was supposed to be a polite way of showing respect those who were socially inferior to you; our modern use of the term probably says a lot about what Virginians actually did with it.

我们的“屈尊”一词来自于,弗吉尼亚的领袖应该对自己的下级表示的一种礼仪性态度。最初屈尊应该是一种礼貌的方式,对社会等级比自己低的人表示尊敬;我们现在对这个词的用法,很可能反映了当时弗吉尼亚人是怎么使用它的。

In a lot of ways, Virginia was the opposite of Massachusetts. Their homicide rate was sky-high, and people were actively encouraged to respond to slights against their honor with duels (for the rich) and violence (for the poor). They were obsessed with gambling, and “made bets not merely on horses, cards, cockfights, and backgammon, but also on crops, prices, women, and the weather”.

在很多方面,弗吉尼亚是马萨诸塞的反面。他们的谋杀率非常高,而人们实际上被鼓励用决斗(富人)和暴力(穷人)来回应对他们荣誉的轻慢。他们沉迷于赌博,“不仅仅在马,扑克,斗鸡,和十五子棋上打赌,而且还在庄稼,价格,妇女和天气上下注”。

Their cuisine focused on gigantic sumptuous feasts of animals killed in horrible ways. There were no witchcraft trials, but there

were people who were fined for disrupting the peace by accusing their neighbors of witchcraft. Their church sermons were twenty minutes long on the dot.

他们的饮食注重巨大奢靡的欢宴,充斥着用各种可怕方法杀死的动物。这里没有女巫审判,倒是有人因为指控其邻居是女巫而犯了寻衅滋事被罚款的。他们的教会布道只有20分钟那么长。

The Puritans naturally thought of the Virginians as completely lawless reprobate sinners, but this is not

entirelytrue. Virginian church sermons might have been twenty minutes long, but Virginian ballroom dance lessons could last nine hours. It wasn’t that the Virginians weren’t bound by codes, just that those codes were social rather than moral.

清教徒自然认为弗吉尼亚人是完全不遵法纪的邪恶罪人,但是这并不是完全正确的。弗吉尼亚教会的讲道也许只有20分钟,但其舞池中的交谊舞教学课可以长达九小时。并不是弗吉尼亚人不受法规约束,只是这些法规是社交上的,而不是道德上的。

And Virginian nobles weren’t just random jerks, they were

carefully cultivated jerks. Planters spared no expense to train their sons to be strong, forceful, and not take nothin’ from nobody. They would encourage and reward children for being loud and temperamental, on the grounds that this indicated a strong personality and having a strong personality was fitting of a noble.

而且弗吉尼亚贵族并不仅仅是混蛋,他们是被精心教化过的混蛋。种植园主不惜代价训练他们的儿子,令其强壮、坚决,不受任何人摆弄。他们会因孩子们声音洪亮、感情激烈而加以鼓励和奖励,因为这意味着强烈的个性,而有强烈个性和做一个贵族是相符的。

When this worked, it worked

really well – witness natural leaders and self-driven polymaths like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. More often it failed catastrophically – the rate of sex predation and rape in Virginia was at least as high as anywhere else in North America.

当这种做法奏效时,它确实有很好的效果——天然的领袖和自我激励的博学者例如乔治·华盛顿和托马斯·杰弗逊即是明证。更多的时候,这做法导致了灾难性的失败,弗吉尼亚的性侵犯和强奸率至少和北美其他地方一样高。

The Virginian Cavaliers had an obsession with liberty, but needless to say it was not exactly a sort of liberty of which the ACLU would approve. I once heard someone argue against libertarians like so: even if the government did not infringe on liberties, we would still be unfree for other reasons. If we had to work, we would be subject to the whim of bosses. If we were poor, we would not be “free” to purchase most of the things we want. In any case, we are “oppressed” by disease, famine, and many other things besides government that prevent us from implementing our ideal existence.

弗吉尼亚骑士党着迷于自由,但是不用说,这自由不完全等同于美国民权自由联盟(ACLU)所支持的那种自由。我曾听某人和自由意志主义者做如此争辩:即使政府不侵犯我们的自由,我们仍然会因为其他原因不自由。如果我们必须工作,我们就会被老板的兴之所至所限制。如果我们贫穷,我们就不可能“自由的”购买我们所需的大部分物品。在任何时候,我们都会被疾病、饥饿和其他很多政府之外的事情“压迫”,来阻止我们达到理想的状态。

The Virginians took this idea and ran with it – in the wrong direction. No, they said, we

wouldn’t be free if we had to work, therefore we insist upon not working. No, we

wouldn’t be free if we were limited by poverty, therefore we insist upon being extremely rich. Needless to say, this conception of freedom required first indentured servitude and later slavery to make it work, but the Virginians never

claimed that the servants or slaves were free.

弗吉尼亚人采纳了这个主意,并且践行了它——在错误的方向上。不,他们说,如果我们必须工作,我们不可能自由,所以我们坚持不工作。不,如果我们被贫穷限制,我们不可能自由,所以我们坚持要极度的富有。无需多言,要实行这种自由观念,起先要求契约仆人的服侍,而后要求奴隶的劳动,但弗吉尼亚人从来没有宣称仆人或奴隶是自由的。

That wasn’t the point. Freedom, like wealth, was properly distributed according to rank; nobles had as much as they wanted, the middle-class enough to get by on, and everyone else none at all. And a Virginian noble would have gone to his grave insisting that a civilization without slavery could never have citizens who were truly free.

问题不在这里。自由,像财富一样,按照等级进行恰当分配;贵族想要多少就要多少,中间阶层也得到了足够的,而其他人则什么也没有。一个弗吉尼亚贵族可能至死都会坚持:没有奴隶制的文明,不可能有真正自由的公民。

C: The Quakers

C:贵格会

Fischer warns against the temptation to think of the Quakers as normal modern people, but he has to warn us precisely because it’s so tempting. Where the Puritans seem like a dystopian caricature of virtue and the Cavaliers like a dystopian caricature of vice, the Quakers just seem

ordinary. Yes, they’re kind of a religious cult, but they’re the kind of religious cult any of us might found if we were thrown back to the seventeenth century.

Fischer警告我们小心那种想要把贵格会看作正常现代人的倾向,但是他之所以不得不警告我们,恰好就是因为这种想法是如此诱人。清教徒看上去像关于德行的敌托邦讽刺画,骑士党看起来像关于邪恶的敌托邦讽刺画,而贵格会则看起来刚好正常。是的,他们是一种教派,但是他们是那种我们中任何人如果穿越回17世纪都会成立的教派。

Instead they were founded by a weaver’s son named George Fox. He believed people were basically good and had an Inner Light that connected them directly to God without a need for priesthood, ritual, Bible study, or self-denial; mostly people just needed to listen to their consciences and be nice. Since everyone was equal before God, there was no point in holding up distinctions between lords and commoners: Quakers would just address everybody as “Friend”.

其实贵格会是被一个纺织工的儿子George Fox创立的。他相信,人基本上是善的,而且人心有内在的光亮,可以把人和上帝直接联系起来,不需要牧师、仪式、解经或者自我否定;大部分时候,人只需要听从他们良心的召唤,为人友善。因为每个人在神面前都是平等的,所以没有任何理由坚持领主和平民之间的分别:贵格会对每个人都以“朋友”称呼。

And since the Quakers were among the most persecuted sects at the time, they developed an insistence on tolerance and freedom of religion which (unlike the Puritans) they stuck to even when shifting fortunes put them on top. They believed in pacificism, equality of the sexes, racial harmony, and a bunch of other things which seem pretty hippy-ish even today let alone in 1650.

而且因为贵格会在当时是最受迫害的宗派,他们发展出了对宗教宽容和信仰自由的坚持,这点不像清教徒。他们甚至在自身有幸掌权时,仍然坚持这点。他们信仰和平主义、性别平等、种族和谐,以及其他很多即使在今天看来都很嬉皮士的观念,更遑论在1650年。

England’s top Quaker in the late 1600s was William Penn. Penn is universally known to Americans as “that guy Pennsylvania is named after” but actually was a larger-than-life 17th century superman. Born to the nobility, Penn distinguished himself early on as a military officer; he was known for beating legendary duelists in single combat and then sparing their lives with sermons about how murder was wrong.

17世纪晚期,英国最重要的贵格会信徒是William Penn。对大多数美国人而言,他只是因“宾夕法尼亚以其得名”而广为人知。但其实,他是17世纪的超凡人物。生于贵族之家,Penn早年担任军官,崭露头角;他因以下事迹而著名:在一对一决斗中击败传奇般的对手们,而后饶过其性命,并发表讲道,指出谋杀是错误的。

He gradually started having mystical visions, quit the military, and converted to Quakerism. Like many Quakers he was arrested for blasphemy; unlike many Quakers, they couldn’t make the conviction stick; in his trial he “conducted his defense so brilliantly that the jurors refused to convict him even when threatened with prison themselves, [and] the case became a landmark in the history of trial by jury.”

渐渐的,他开始经历神秘的异象,退出军旅,改宗成为贵格会信徒。就像很多贵格会信徒一样,他因渎神被逮捕;和许多贵格会信徒不同,审判者没能给他定罪;在审判中,他“如此精彩的辩护,以至于陪审团成员甚至在面对牢狱之灾威胁时,都不肯定他的罪,而且该案成为了陪审团审判历史上的里程碑。”

When the state finally found a pretext on which to throw him in prison, he spent his incarceration composing “one of the noblest defenses of religious liberty ever written”, conducting a successful mail-based courtship with England’s most eligible noblewoman, and somehow gaining the personal friendship and admiration of King Charles II.

当政府终于找到借口将其投入监狱时,他在狱中创作了“有史以来,对宗教自由的最高贵辩护之一的文章”,以信件形式向英国最有贵族资格的女士成功求爱,而且不知何故得到了查理二世的个人友谊和敬佩。

Upon his release the King liked him so much that he gave him a large chunk of the Eastern United States on a flimsy pretext of repaying a family debt. Penn didn’t

want to name his new territory Pennsylvania – he recommended just “Sylvania” – but everybody else overruled him and Pennyslvania it was.

获释之后,国王如此喜爱他,以至于把美国东部的一大片以偿还家庭债务的单薄借口划给了他。Penn不想把他的新领地命名为宾夕法尼亚——他推荐的命名仅仅是“夕法尼亚”——但是其他所有人否决了他的意见,宾夕法尼亚就这样得名。

The grant wasn’t quite the same as the modern state, but a chunk of land around the Delaware River Valley – what today we would call eastern Pennsylvania, northern Delaware, southern New Jersey, and bits of Maryland – centered on the obviously-named-by-Quakers city of Philadelphia.

授予Penn的这份领地和现在宾州的疆域并不完全一样,而是德拉维尔河谷周围的一大片土地——今天我们称为宾夕法尼亚东部、德拉维尔北部、新泽西南部,以及很小一部分马里兰州的地区——该地区的中心的费城,显然是由贵格会命名的【

编注:Philadelphia一词希腊文本意为“兄弟情谊”】。

Penn decided his new territory would be a Quaker refuge – his exact wording was “a colony of Heaven [for] the children of the Light”. He mandated universal religious toleration, a total ban on military activity, and a government based on checks and balances that would “leave myself and successors no power of doing mischief, that the will of one man may not hinder the good of a whole country”.

Penn决定把他的新领土变成贵格会的避难地——他的原话是“一个面向圣光之子们的天国殖民地”。他强制实施普遍的宗教宽容,完全禁止军事活动,基于分权和制衡的政府将“不会给我自己和继任者留下作恶的权力,个人的意志不会妨害整个国家的益处”。

His recruits – about 20,000 people in total – were Quakers from the north of England, many of them minor merchants and traders. They disproportionately included the Britons of Norse descent common in that region, who formed a separate stratum and had never really gotten along with the rest of the British population. They were joined by several German sects close enough to Quakers that they felt at home there; these became the ancestors of (among other groups) the Pennsylvania Dutch, Amish, and Mennonites.

他招募了总共大约两万人——他们是英格兰北部的贵格会信徒,很多是小商小贩。不成比例地,他们中很多是那个区域很常见的具有北欧血统的英国人,构成了不列颠的一个特殊阶层,并且从未和其他不列颠人真正融合在一起。几个和贵格会近似的德国宗派加入了他们,教义相似使得这些人在那里能找到家的感觉;这些人和其他一些团体成为了德裔宾州人、阿米绪人和门诺派的祖先。

INTERESTING QUAKER FACTS:

关于贵格会的有趣事实:

1. In 1690 a gang of pirates stole a ship in Philadelphia and went up and down the Delaware River stealing and plundering. The Quakers got in a heated (but brotherly) debate about whether it was morally permissible to use violence to stop them. When the government finally decided to take action, contrarian minister George Keith dissented and caused a major schism in the faith.

在1690年,一帮海盗在费城偷了一艘船,在德拉维尔河上四处偷盗劫掠。贵格会信徒们展开了一场激烈(但是兄弟般的)辩论,讨论用暴力阻止这帮海盗在道德上是否合理。当政府最终决定采取行动,持反对意见的牧师George Keith表示不同意,并引发了信仰上的一次重大分裂。

2. Fischer argues that the Quaker ban on military activity within their territory would have doomed them in most other American regions, but by extreme good luck the Indians in the Delaware Valley were almost as peaceful as the Quakers. As usual, at least some credit goes to William Penn, who taught himself Algonquin so he could negotiate with the Indians in their own language.

Fischer认为贵格会在他们的领土上禁止军事活动,在全美大部分别的地区可能都会给他们带来悲惨的命运。然而非常幸运的是,德拉维尔谷地的印第安人几乎和贵格会会众一样和平。和通常一样,这至少部分功绩归于William Penn,他自学了Algonquin语,所以他可以用印第安人的母语与其谈判。

3. The Quakers’ marriage customs combined a surprisingly modern ideas of romance, with extreme bureaucracy. The wedding process itself had sixteen stages, including “ask parents”, “ask community women”, “ask community men”, “community women ask parents”, and “obtain a certificate of cleanliness”. William Penn’s marriage apparently had forty-six witnesses to testify to the good conduct and non-relatedness of both parties.

贵格会信徒的婚姻习俗结合了令人惊讶的现代浪漫创意和极端的官僚化。婚姻过程本身有十六个阶段,包括“问询父母”,“问询社区里的妇人”,“问询社区里的男人”,“社区里的妇人问询父母”,以及“获得一个清白认证”。William Penn的婚姻显然有46位证人,见证夫妻双方都德行良好,没有亲属关系。

4. Possibly related: 16% of Quaker women were unmarried by age 50, compared to only about 2% of Puritans.

可能相关的事实:16%的贵格会妇女到50岁时都没有结婚,清教徒中这一数字仅为2%。

5. Quakers promoted gender equality, including the (at the time scandalous) custom of allowing women to preach (condemned by the Puritans as the crime of “she-preaching”).

贵格会推行性别平等,包括允许妇女讲道(在那时算是丑闻,被清教徒谴责为“妇女讲道”罪)

6. But they were such prudes about sex that even

the Puritansthought they went too far. Pennsylvania doctors had problems treating Quakers because they would “delicately describe everything from neck to waist as their ‘stomachs’, and anything from waist to feet as their ‘ankles'”.

但是他们对性十分的正经,甚至清教徒都认为他们在这方面走得太远。宾州医生在治疗贵格会会众时会遇到麻烦,因为他们“故意把所有从颈到腰的部位都称为‘肚子’,而任何从腰到脚的地方都称为‘脚踝’”。

7. Quaker parents Richard and Abigail Lippincott named their eight children, in order, “Remember”, “John”, “Restore”, “Freedom”, “Increase”, “Jacob”, “Preserve”, and “Israel”, so that their names combined formed a simple prayer.

贵格会的一对父母Richard和Abigail Lippincott把他们的八个孩子按顺序起名叫做,“记得”,“约翰”,“恢复”,“自由”,“增加”,“雅各”,“存留”,“以色列”,他们的名字合起来构成一个简单的祷词。

8. Quakers had surprisingly modern ideas about parenting, basically sheltering and spoiling their children at a time when everyone else was trying whip the Devil out of them.

贵格会在教养孩童方面有着令人惊讶的现代观点,在那个其他人都试图从孩子身上赶出魔鬼的时代,他们基本上是保护和宠爱孩子的。

9. “A Quaker preacher, traveling in the more complaisant colony of Maryland, came upon a party of young people who were dancing merrily together. He broke in upon them like an avenging angel, stopped the dance, and demanded to know if they considered Martin Luther to be a good man. The astonished youngsters answered in the affirmative. The Quaker evangelist then quoted Luther on the subject of dancing: ‘as many paces as the man takes in his dance, so many steps he takes toward Hell. This, the Quaker missionary gloated with a gleam of sadistic satisfaction, ‘spoiled their sport’.”

“一个贵格会的传道人,在更殷勤有礼的马里兰殖民地旅行时,遇到了一群年轻人在欢快的跳舞。他如复仇天使般闯入其中,停止了舞会,要求众人考虑马丁·路德是否是个好人。被惊呆的年轻人给出了肯定的答案。这位贵格会传道人接着引用了路德关于跳舞的评论:‘一个人在舞蹈中跳多少步,就朝地狱走了多少步。’这个贵格会传道人带着一种施虐的快感吹嘘,‘毁掉了他们的活动’。”

10. William Penn wrote about thirty books defending liberty of conscience throughout his life. The Quaker obsession with the individual conscience as the work of God helped invent the modern idea of conscientious objection.

终其一生,William Penn写下了约三十本书,为良心自由辩护。贵格会着迷于把个人良心看作是上帝的造物,这促进了因良心拒绝服兵役这一现代观念的产生。

11. Quakers were heavily (and uniquely for their period) opposed to animal cruelty. When foreigners introduced bullbaiting into Philadelphia during the 1700s, the mayor bought a ticket supposedly as a spectator. When the event was about to begin, he leapt into the ring, personally set the bull free, and threatened to arrest anybody who stopped him.

贵格会会众十分强力的反对虐待动物(在他们的时代,这是很独特的)。当外地人在18世纪把猎犬咬牛游戏引入费城时,市长买了一张票,本应作为观众呆在现场。当活动快开始时,他跃入场地,自己把牛放走,并威胁逮捕任何阻止他的人。

12. On the other hand, they were also opposed to other sports for what seem like kind of random reasons. The town of Morley declared an anathema against foot races, saying that they were “unfruitful works of darkness”.

在另一方面,他们借着各种任意的理由,反对各种其他运动。Morley镇宣布取缔长跑,因为长跑是“黑暗徒劳的工作”。

13. The Pennsylvania Quakers became very prosperous merchants and traders. They also had a policy of loaning money at low- or zero- interest to other Quakers, which let them outcompete other, less religious businesspeople.

宾夕法尼亚的贵格会信徒成了非常兴旺的商人。他们也有着一项以低利率或零利率贷款给其他贵格会成员的政策,这使得贵格会会众比其他更少宗教化的人更有竞争优势。

14. They were among the first to replace the set of bows, grovels, nods, meaningful looks, and other British customs of acknowledging rank upon greeting with a single rank-neutral equivalent – the handshake.

把英国的等级化问候动作,如鞠躬、下拜、点头、注目礼等等,更换为不具有等级意味的握手礼,贵格会是首先实施这种变革的群体之一。

15. Pennsylvania was one of the first polities in the western world to abolish the death penalty.

宾夕法尼亚是在西方世界首先废除死刑的政治体之一。

16. The Quakers were lukewarm on education, believing that too much schooling obscured the natural Inner Light. Fischer declares it “typical of William Penn” that he wrote a book arguing against reading too much.

贵格会会众对教育有些冷淡,认为太多学校教育会掩蔽人内心自然的灵性之光。Fischer宣称这是“William Penn的典型做法”,他写了一本书来反对过多的阅读。

17. The Quakers not only instituted religious freedom, but made laws against mocking another person’s religion.

贵格会会众不仅仅制定了宗教自由制度,还颁布法律,禁止嘲笑他人的宗教。

18. In the late 1600s as many as 70% of upper-class Quakers owned slaves, but Pennsylvania essentially invented modern abolitionism. Although their colonial masters in England forbade them from banning slavery outright, they applied immense social pressure and by the mid 1700s less than 10% of the wealthy had African slaves. As soon as the American Revolution started, forbidding slavery was one of independent Pennsylvania’s first actions.

在17世纪晚期,多达70%的上层贵格会人士拥有奴隶,但是宾夕法尼亚的确发明了现代废奴主义。虽然他们在英国的殖民地宗主们不准他们公然废除奴隶制,但是他们施加了巨大的社会压力,到18世纪中叶,少于10%的富裕阶层拥有黑奴。美国革命一开始,废奴就成为了宾州独立后的第一批举措之一。

Pennsylvania was

very successful for a while; it had some of the richest farmland in the colonies, and the Quakers were exceptional merchants and traders; so much so that they were forgiven their military non-intervention during the Revolution because of their role keeping the American economy afloat in the face of British sanctions.

宾夕法尼亚曾非常成功;它拥有殖民地当中最肥沃的农地,贵格会会众是出色的商人;这些优势如此之大,以至于独立战争期间,他们的军事不干涉态度得到了原谅,因为面临英国的制裁,他们起到了支撑美国经济的作用。

But by 1750, the Quakers were kind of on their way out; by 1750, they were a demographic minority in Pennsylvania, and by 1773 they were a minority in its legislature as well. In 1750 Quakerism was the third-largest religion in the US; by 1820 it was the ninth-largest, and by 1981 it was the sixty-sixth largest.

但是到1750年代,贵格会信徒日渐式微;到1750年,他们变成了宾州人口上的少数派,到1773年,他们又变成了宾州立法机构中的少数。在1750年,贵格主义是美国的第三大宗教;到1820年,变成了第九大,到1981年,变成了第六十六大。

What happened? The Quakers basically tolerated themselves out of existence. They were so welcoming to religious minorities and immigrants that all these groups took up shop in Pennsylvania and ended its status as a uniquely Quaker society. At the same time, the Quakers themselves became more “fanatical” and many dropped out of politics believing it to be too worldly a concern for them; this was obviously fatal to their political domination.

发生了什么呢?贵格会信徒基本上是因宽容而使得他们自己逐步消逝。他们如此欢迎少数教派和移民,这些人占据了宾州,结束了宾州贵格会一统天下的状态。同时,贵格会自身变得更具属灵热忱,许多人从政治领域退出,他们认为该领域对于他们而言属于过于世俗的关怀;这对于他们的政治影响力显然是致命的。

The most famous Pennsylvanian statesman of the Revolutionary era, Benjamin Franklin, was not a Quaker at all but a first-generation immigrant from New England. Finally, Quakerism was naturally extra-susceptible to that thing where Christian denominations become indistinguishable from liberal modernity and fade into the secular background.

独立战争时期最著名的宾州政治家是本杰明·富兰克林。他完全不是贵格会信徒,而是来自新英格兰的第一代移民。最后,贵格主义自然而然地特别易于受这一趋势影响:即基督教派日渐变得和自由主义现代性难以区分,从而渐渐融于世俗背景中去。

But Fischer argues that Quakerism continued to shape Pennsylvania long after it had stopped being officially in charge, in much the same way that Englishmen themselves have contributed disproportionately to American institutions even though they are now a numerical minority. The Pennsylvanian leadership on abolitionism, penal reform, the death penalty, and so on all happened

after the colony was officially no longer Quaker-dominated.

但是Fischer争辩说,在退出官方主导地位后,贵格主义的影响在宾州持续了很长一段时间,正如英国裔本身对美国的制度有着不成比例的巨大贡献那样,即使他们现在是数量上的少数派。宾州在废奴、刑罚改革、死刑等等方面的领袖地位全部出现在该殖民地官方不再被贵格会掌控之后。

And it’s hard not to see Quaker influence on the ideas of the modern US – which was after all founded in Philadelphia. In the middle of the Puritans demanding strict obedience to their dystopian hive society and the Cavaliers demanding everybody bow down to a transplanted nobility, the Pennsylvanians – who became the thought leaders of the Mid-Atlantic region including to a limited degree New York City – were pretty normal and had a good opportunity to serve as power-brokers and middlemen between the North and South. Although there are seeds of traditionally American ideas in every region, the Quakers really stand out in terms of freedom of religion, freedom of thought, checks and balances, and the idea of universal equality.

而且,很难忽略贵格会对现代美国理念上的影响——不管如何,现代美国创建于费城。清教徒严格要求服从他们的敌托邦集体主义社会,骑士党人要求每个人都在移植的贵族制度中鞠躬,介于两者之间,宾夕法尼亚人——作为中大西洋地区,一定程度上也包括纽约市的思想领袖——则相当正常,并且有很好的机会作为南方和北方的中间人和权力经纪人。虽然在每个区域都有美国传统观念的种子,贵格会在宗教自由、思想自由、分权制衡和普世平等理念上真的表现很突出。

It occurs to me that William Penn might be literally the single most successful person in history. He started out as a minor noble following a religious sect that everybody despised and managed to export its principles to Pennsylvania where they flourished and multiplied. Pennsylvania then managed to export

its principles to the United States, and the United States exported them to the world. I’m not sure how much of the suspiciously Quaker character of modern society is a direct result of William Penn, but he was in one heck of a right place at one heck of a right time

我突然想到,William Penn也许真的是史上最成功的个人。一开始,作为一个小贵族,他皈依了一个人人蔑视的宗派,他尽力把该宗派的原则输出到了宾夕法尼亚,让其发扬光大。宾夕法尼亚则尽力把它的原则输出到美国,而美国则将之输出到全世界。我不确定现代社会的贵格会特征有多大可能是William Penn的直接成果,但他的确是一个在非常正确的时间,出现在非常正确的地点的人。

D: The Borderers

D: 边民们

The Borderers are usually called “the Scots-Irish”, but Fischer dislikes the term because they are neither Scots (as we usually think of Scots) nor Irish (as we usually think of Irish). Instead, they’re a bunch of people who lived on (both sides of) the Scottish-English border in the late 1600s.

边民们经常被叫做“苏格兰-爱尔兰人”,但是Fischer不喜欢这个称谓,因为他们既不是如我们通常想象的苏格兰人,也不是如我们通常想象的爱尔兰人。相反,他们是一群17世纪晚期生活在苏格兰-英格兰边界两侧的人。

None of this makes sense without realizing that the Scottish-English border was

terrible. Every couple of years the King of England would invade Scotland or vice versa; “from the year 1040 to 1745, every English monarch but three suffered a Scottish invasion, or became an invader in his turn”. These “invasions” generally involved burning down all the border towns and killing a bunch of people there.

如果没有意识到苏格兰-英格兰边境曾极其可怕,事情就说不通。每隔几年,英格兰的国王就会侵略苏格兰,或者反之;“从1040年到1745年,除了三个君主之外,每个英格兰君主都遭遇过苏格兰的入侵,或者反之变成了入侵者”;这些“入侵”总的来说,就是烧毁所有边境城镇,杀死那地区的一大批人。

Eventually the two sides started getting

pissed with each other and would also torture-murder all of the enemy’s citizens they could get their hands on, ie any who were close enough to the border to reach before the enemy could send in their armies. As if this weren’t bad enough, outlaws quickly learned they could plunder one side of the border, then escape to the other before anyone brought them to justice, so the whole area basically became one giant cesspool of robbery and murder.

最终,双方都被激怒了,开始虐杀所有落入手中的对方平民,也就是任何住的离边境足够近、在敌方军队赶来前就能实施侵害的人。好像嫌这还不够糟,法外匪徒很快学到他们可以在边境一侧抢掠,而后在被绳之以法前,逃到另一边去。所以整个地区基本上是充满抢劫谋杀的血腥地狱。

In response to these pressures, the border people militarized and stayed feudal long past the point where the rest of the island had started modernizing. Life consisted of farming the lands of whichever brutal warlord had the top hand today, followed by being called to fight for him on short notice, followed by a grisly death. The border people dealt with it as best they could, and developed a culture marked by extreme levels of clannishness, xenophobia, drunkenness, stubbornness, and violence.

面对这些压力,边民武装了起来,在大不列颠岛的其他地方已经开始现代化之后很久,他们还保持着封建制度。生活由以下部分构成:耕种土地,这些土地属于当时军阀混战的胜利者,服从突然而至的上战场的征召,面对悲惨的死亡。边民在此条件下,竭力挣扎求活,发展出一种以极端小集团、排外、酗酒、倔强和暴力为特征的文化。

By the end of the 1600s, the Scottish and English royal bloodlines had intermingled and the two countries were drifting closer and closer to Union. The English kings finally got some breathing room and noticed – holy frick, everything about the border is

terrible.

到1600年代末,苏格兰和英格兰的皇族变得血脉相连,两个国家开始接近并组成联邦【

编注:1603年苏格兰国王詹姆斯六世继承英格兰王位,成为英格兰的詹姆斯一世】。此后的英格兰国王们终于缓过气来,并且发现——天哪,边境的一切都很可怕。

They decided to make the region economically productive, which meant “squeeze every cent out of the poor Borderers, in the hopes of either getting lots of money from them or else forcing them to go elsewhere and become somebody else’s problem”. Sometimes absentee landlords would just evict everyone who lived in an entire region,

en masse, replacing them with people they expected to be easier to control.

他们决定让这个地区在经济产出上有效,这意味着“从贫穷边民身上榨出每一分钱,目的是要么从边民那里得到很多收入,要么强迫他们搬到别处,变成他人的麻烦。”有时候,外居的领主会直接把整个区域的居民驱逐,代之以他们预期会更好控制的人。

Many of the Borderers fled to Ulster in Ireland, which England was working on colonizing as a Protestant bulwark against the Irish Catholics, and where the Crown welcomed violent warlike people as a useful addition to their Irish-Catholic-fighting project. But Ulster had some of the same problems as the Border, and also the Ulsterites started worrying that the Borderer cure was worse than the Irish Catholic disease. So the Borderers started getting kicked out of Ulster too, one thing led to another, and eventually 250,000 of these people ended up in America.

许多边民逃到爱尔兰的阿尔斯特,英国人当时正要在此地殖民,将之变成新教针对爱尔兰天主教的堡垒。所以皇室欢迎暴力好战的人,用于补充他们和爱尔兰天主教的斗争工程。但是阿尔斯特也有一些和边境地区相同的麻烦,而阿尔斯特人也开始担忧,边民作为一种解药,也许比爱尔兰天主教这一疾病更糟。所以边民又开始被驱逐出阿尔斯特,事情接踵而至,最终边民中有25万人移居美国。

250,000 people is a

lot of Borderers. By contrast, the great Puritan emigration wave was only 20,000 or so people; even the mighty colony of Virginia only had about 50,000 original settlers. So these people showed up on the door of the American colonies, and the American colonies collectively took one look at them and said “nope”.

25万人可是很大一批。对比之下,清教徒移民大潮只有2万人左右;即使是弗吉尼亚巨大的殖民地,也只有5万初始殖民者。所以当这些人出现在北美殖民地的大门口,各个殖民地一齐打量了他们一下,然后说“不”。

Except, of course, the Quakers. The Quakers talked among themselves and decided that these people were also Children Of God, and so they should demonstrate Brotherly Love by taking them in. They tried that for a couple of years, and then they questioned their life choices and

also said “nope”, and they told the Borderers that Philadelphia and the Delaware Valley were actually kind of full right now but there was lots of unoccupied land in

WesternPennsylvania, and the Appalachian Mountains were very pretty at this time of year, so why didn’t they head out that way as fast as it was physically possible to go?

当然,贵格会会众例外。贵格会内部进行了讨论,认定这些人也是上帝的孩子,所以他们应该彰显兄弟之爱,接纳边民们。他们尝试了几年,然后他们对自己的选择产生了疑问,也转向了说“不”。他们告诉边民,费城和德拉威尔河谷现在其实已经很满了,但是西宾夕法尼亚有很多无主之地,而阿巴拉契亚山脉在这个季节也很好,为什么不向那些方向尽快开拓,趁着自然条件还允许?

At the time, the Appalachians were kind of the booby prize of American colonization: hard to farm, hard to travel through, and exposed to hostile Indians. The Borderers fell in love with them. They came from a pretty marginal and unproductive territory themselves, and the Appalachians were far away from everybody and full of fun Indians to fight.

在那时,阿巴拉契亚的群山对北美殖民者来说,是分给最后一名的奖品:很难耕种,很难通行,暴露于充满敌意的印第安人面前。边民却爱上了它们。他们本就来自贫瘠的边缘化的故土,而阿巴拉契亚群山远离所有人,充满了与印第安人战斗的乐趣。

Soon the Appalachian strategy became the accepted response to Borderer immigration and was taken up from Pennsylvania in the north to the Carolinas in the South (a few New Englanders hit on a similar idea and sent their own Borderers to colonize the mountains of New Hampshire).

很快,阿巴拉契亚策略成为了对移入边民的既定策略,北到宾夕法尼亚,南到卡罗莱纳的殖民地都加以采纳(几个新英格兰殖民地也想出了相似的办法,把他们自己的边民打发到新罕布什尔的群山去殖民)。

So the Borderers all went to Appalachia and established their own little rural clans there and nothing at all went wrong except for the entire rest of American history.

所以边民们都去了阿巴拉契亚,建立了他们自己的小群农村宗族,一切都相安无事,除了整个美国历史被大大影响。

INTERESTING BORDERER FACTS:

关于边民的有趣事实:

1. Colonial opinion on the Borderers differed within a very narrow range: one Pennsylvanian writer called them “the scum of two nations”, another Anglican clergyman called them “the scum of the universe”.

对边民,殖民地人们的看法相去不远:一个宾夕法尼亚作家把他们叫做“两个国家之间的渣滓”,另一个国教会牧师把他们叫做“宇宙的渣滓”。

2. Some Borderers tried to come to America as indentured servants, but after Virginian planters got some experience with Borderers they refused to accept any more.

一些边民试图以契约仆人身份来美国,但是在弗吉尼亚种植园主得到了一些关于边民的教训后,他们不再接收边民。

3. The Borderers were mostly Presbyterians, and their arrival

en massestarted a race among the established American denominations to convert them. This was mostly unsuccessful; Anglican preacher Charles Woodmason, an important source for information about the early Borderers, said that during his missionary activity the Borderers “disrupted his service, rioted while he preached, started a pack of dogs fighting outside the church, loosed his horse, stole his church key, refused him food and shelter, and gave two barrels of whiskey to his congregation before a service of communion”.

边民们大部分是长老会信徒,他们的成群到达开启了一场其他既有美国宗派转化他们的竞赛。基本上,这是不成功的;国教会传道人 Charles Woodmason是研究早期边民的重要资料来源。他说在他的传道活动期间,边民“打断他的侍奉,在其讲道时作乱,在教会外面斗狗,放了他的马,偷了他的教堂钥匙,拒绝给他食物和住宿,在一次擘饼聚会时,给他的会众两桶威士忌。

4. Borderer town-naming policy was very different from the Biblical names of the Puritans or the Ye Olde English names of the Virginians. Early Borderer settlements include – just to stick to the creek-related ones – Lousy Creek, Naked Creek, Shitbritches Creek, Cuckold’s Creek, Bloodrun Creek, Pinchgut Creek, Whipping Creek, and Hangover Creek. There were also Whiskey Springs, Hell’s Half Acre, Scream Ridge, Scuffle town, and Grab town. The overall aesthetic honestly sounds a bit Orcish.

边民的集镇命名规则非常不同于清教徒的圣经命名法,或者弗吉尼亚人的仿古英文命名法。早期边民殖民点中和溪流有关的名字有——糟糕溪,裸露溪,烂裤衩溪,戴绿帽溪,流血溪,吃不饱溪,鞭打溪,以及宿醉溪。当然,也有威士忌泉,地狱半英亩,尖叫岭,混战镇,揪住镇。总体审美的确听来有些野蛮。

5. One of the first Borderer leaders was John Houston. On the ship over to America, the crew tried to steal some of his possessions; Houston retaliated by leading a mutiny of the passengers, stealing the ship, and sailing it to America himself. He settled in West Virginia; one of his descendants was famous Texan Sam Houston.

第一代边民的领袖之一是约翰·休斯顿。在来美国的船上,船员试图偷窃他的财产;作为报复,他领导乘客发动事变,劫持了船,自己航行到美国。他在西弗吉尼亚安顿下来,后代之一,就是著名的德州佬山姆·休斯顿。

6. Traditional Borderer prayer: “Lord, grant that I may always be right, for thou knowest I am hard to turn.”

传统的边民祷词:“上帝,让我一直都走对路吧,因为你最清楚,我是难以回转的。”

7. “The back country folk bragged that one interior county of North Carolina had so little ‘larnin’ that the only literate inhabitant was elected ‘county reader'”

“荒野的乡民吹嘘北卡的一个内陆郡是如此的缺乏‘蚊化’,以至于唯一识字的定居者被选为“‘郡阅读员’”。

8. The Borderer accent contained English, Scottish, and Irish elements, and is (uncoincidentally) very similar to the typical “country western singer” accent of today.

边民的口音包括了英格兰、苏格兰和爱尔兰元素,而且并非巧合,它和今天的“乡村西部歌手”腔调十分相似。

9. The Borderers were famous for family feuds in England, including the Johnson clan’s habit of “adorning their houses with the flayed skins of their enemies the Maxwells in a blood feud that continued for many generations”. The great family feuds of the United States, like the Hatfield-McCoy feud, are a direct descendent of this tradition.

边民在英格兰以家族世仇闻名,包括Johnson宗族的习惯:“在持续多代的血腥世仇中,用他们的敌人,Maxwells家族身上剥下来的皮装饰自己的房子”。在美国,大型的家族世仇,比如Hatfield家族与McCoy家族的世仇,则直接继承自这种传统。

10. Within-clan marriage was a popular Borderer tradition both in England and Appalachia; “in the Cumbrian parish of Hawkshead, for example, both the bride and the groom bore the same last names in 25 percent of all marriages from 1568 to 1704”. This led to the modern stereotype of Appalachians as inbred and incestuous.

在英格兰和阿巴拉契亚,宗族内婚都是边民流行的传统;“例如在Hawkshead的Cumbrian教区,从1568年到1704年,25%的新郎和新娘都有着相同的姓。”这导致了现代对阿巴拉契亚山民的刻板印象:近亲繁殖和内婚盛行。

11. The Borderers were extremely patriarchal and anti-women’s-rights to a degree that appalled even the people of the 1700s.

边民极端家长制,反对女权,其极端程度甚至吓坏了十八世纪的人们。

12. “In the year 1767, [Anglican priest] Charles Woodmason calculated that 94 percent of backcountry brides whom he had married in the past year were pregnant on their wedding day”

“在1767年,国教会牧师Charles Woodmason统计,上一年度他主持结婚的乡下新娘中有94%在婚礼之日已经怀孕了。”

13. Although the Borderers started off Presbyterian, they were in constant religious churn and their territories were full of revivals, camp meetings, born-again evangelicalism, and itinerant preachers. Eventually most of them ended up as what we now call Southern Baptist.

虽然边民本来信长老会,但他们持续处于信仰流失中,而他们的领地上则充满了复兴、营会、重生福音主义和巡回布道者。最终,他们中大部分变成了我们现在所称的南方浸信会信徒。

14. Borderer folk beliefs: “If an old woman has only one tooth, she is a witch”, “If you are awake at eleven, you will see witches”, “The howling of dogs shows the presence of witches”, “If your shoestring comes untied, witches are after you”, “If a warm current of air is felt, witches are passing”. Also, “wet a rag in your enemy’s blood, put it behind a rock in the chimney, and when it rots your enemy will die”; apparently it was not a coincidence they were thinking about witches so much.

边民相信:“如果一个老妇人只有一颗牙,她就是个女巫”,“如果你在11点醒来,你会看到女巫”,“嚎叫的狗显示了女巫的存在”,“如果你的鞋带松了,女巫在跟着你”,“如果空气中有一股暖流,女巫正在经过”。而且,“用抹布沾湿敌人的血,把它放在烟囱里的一块石头后面,当它烂掉,你的敌人就会死了”;显然,他们如此多的考虑女巫,不是巧合。

15. Borderer medical beliefs: “A cure for homesickness is to sew a good charge of gunpowder on the inside of ths shirt near the neck”. That’ll cure homesickness, all right.

边民的医疗观念:“治疗思乡的方子是在衬衫靠近脖子的部位缝上大量火药”。好吧,这会治好乡愁。

16. More Borderer medical beliefs: “For fever, cut a black chicken open while alive and bind it to the bottom of your foot”, “Eating the brain of a screech owl is the only dependable remedy for headache”, “For rheumatism, apply split frogs to the feet”, “To reduce a swollen leg, split a live cat and apply while still warm”, “Bite the head off the first butterfly you see and you will get a new dress”, “Open the cow’s mouth and throw a live toad-frog down her throat. This will cure her of hollow-horn”. Also, blacksmiths protected themselves from witches by occasionally throwing live puppies into their furnaces.

边民的其他医疗观念:“如果发烧,活活剖开一只黑鸡,把它绑在你的脚底”,“吃掉尖叫猫头鹰的脑子是唯一可靠的治头痛药方”,“对风湿病,在脚上绑上撕开的青蛙”,“为了给腿消肿,劈开一只活猫,趁还温热敷上”,“把你见到的第一只蝴蝶的头拽掉,你会得到一件新裙子”,“把奶牛的嘴打开,扔一只活的癞蛤蟆到它喉咙里。这会治好它的空角病”。而且,铁匠们为了避免女巫的危害,会时不时把活着的小狗扔进他们的炉子里。

17. Rates of public schooling in the backcountry settled by the Borderers were “the lowest in British North America” and sometimes involved rituals like “barring out”, where the children would physically keep the teacher out of the school until he gave in and granted the students the day off.

边民乡村的公共学校入学率是“北美英国殖民地”中最低的,而且有些时候会发生“封门”的仪式,即孩子们会用身体阻挡教师进入学校,除非他让步并给学生们当天放假。

18. “Appalachia’s idea of a moderate drinker was the mountain man who limited himself to a single quart [of whiskey] at a sitting, explaining that more ‘might fly to my head’. Other beverages were regarded with contempt.”

“阿巴拉契亚关于适度饮酒的理念是,一个山民会克制自己一次只喝一夸脱以下的威士忌,解释是喝更多‘也许会让我的脑袋发晕’。其他饮品则是被轻视的。”

19. A traditional backcountry sport was “rough and tumble”, a no-holds-barred form of wrestling where gouging out your opponent’s eyes was considered perfectly acceptable and in fact sound strategy. In 1772 Virginia had to pass a law against “gouging, plucking, or putting out an eye”, but this was the Cavalier-dominated legislature all the way on the east coast and nobody in the backcountry paid them any attention. Other traditional backcountry sports were sharpshooting and hunting.

一项传统的乡下运动是“混战”,一种无规则限制的摔角,在运动中挖掉对手的眼睛被认为是完全可以接受,且实际上非常有效的策略。在1772年弗吉尼亚被迫通过一项法律反对“抠,挖,挤出眼球”,但这是骑士党主导的法律,只在东海岸有效,在阿巴拉契亚的山民根本不理会。另一项传统的乡下运动则是射击和打猎。

20. The American custom of shooting guns into the air to celebrate holidays is 100% Borderer in origin.

美国向天鸣枪庆祝节日的传统100%来自于山民。

21. The justice system of the backcountry was heavy on lynching, originally a race-neutral practice and named after western Virginian settler William Lynch.

山民地区的法律体系非常依赖于私刑审判,这种做法(原本并无种族倾向)即以西弗吉尼亚殖民者William Lynch得名。【

编注:lynch一词在内战后常常特指美国南方白人种族主义者针对黑人的私刑。】

22. Scottish Presbyterians used to wear red cloth around their neck to symbolize their religion; other Englishmen nicknamed them “rednecks”. This

maybe the origin of the popular slur against Americans of Borderer descent, although many other etiologies have been proposed. “Cracker” as a slur is attested as early as 1766 by a colonist who says the term describes backcountry men who are great boasters; other proposed etymologies like slaves talking about “whip-crackers” seem to be spurious.

苏格兰长老会教徒曾在脖子周遭围上红布来象征他们的宗教;其他英国人昵称其为“红脖”。这也许是这一对美国边民后裔的流行贬称的起源,虽然有很多其他的语源学解释也被提出过。“大话精”则是另一个贬称,验证发现,早在1766年一个殖民者曾以该词表示边民们中的吹牛者;其他语源学解释包括奴隶们谈到的“挥鞭子的人”,看来是谬误的。

This is not to paint the Borderers as universally poor and dumb – like every group, they had an elite, and some of their elite went on to become some of America’s most important historical figures. Andrew Jackson became the first Borderer president, behaving

exactly as you would expect the first Borderer president to behave, and he was followed by almost a dozen others. Borderers have also been overrepresented in America’s great military leaders, from Ulysses Grant through Teddy Roosevelt (3/4 Borderer despite his Dutch surname) to George Patton to John McCain.

并不是说边民普遍贫穷愚笨——如同每个群体一样,他们也有精英,有些精英成了美国史上最重要的历史人物之一。Andrew Jackson成为第一任边民总统,其作为和你预期的第一任边民总统会做的一样,他之后又有十多个边民总统。边民在美国伟大军事领袖中的比例也高得过分,从尤利西斯·格兰特到泰迪·罗斯福(3/4的边民血统,虽然他有个荷兰裔姓氏),再到乔治·巴顿,再到约翰·麦凯恩。

The Borderers

really liked America – unsurprising given where they came from – and started identifying as American earlier and more fiercely than any of the other settlers who had come before. Unsurprisingly, they strongly supported the Revolution – Patrick Henry (“Give me liberty or give me death!”) was a Borderer. They also also played a disproportionate role in westward expansion.

边民真的很爱美国——考虑到他们来自何处,这不奇怪——而且他们产生美国人的自我认同比其他在他们之前到的殖民者更早,程度更强烈。并不奇怪的是,他们强烈支持独立革命——Patrick Henry(“不自由,宁毋死!”)是个边民。他们也在西进运动中发挥了不成比例的重要作用。

After the Revolution, America made an almost literal 180 degree turn and the “backcountry” became the “frontier”. It was the Borderers who were happiest going off into the wilderness and fighting Indians, and most of the famous frontiersmen like Davy Crockett were of their number. This was a big part of the reason the Wild West was so wild compared to, say, Minnesota (also a frontier inhabited by lots of Indians, but settled by Northerners and Germans) and why it inherited seemingly Gaelic traditions like cattle rustling.

革命后,美国实际上是180度转向,“内地”变成了“边疆”。对于深入荒野,和印第安人战斗,边民是最开心的,大部分著名的边疆拓荒者如Davy Crockett即是其中一员。很大程度上,这就是为什么狂野西部是如此狂野,相比于比如说明尼苏达(也是个有很多印第安人定居的边疆地带,但是由北方人和德国裔开拓殖民),这也解释了为何西部有套小牛的传统,这疑似是苏格兰盖尔人的传统。

Their conception of liberty has also survived and shaped modern American politics: it seems essentially to be the modern libertarian/Republican version of freedom from government interference, especially if phrased as “get the hell off my land”, and

especially especially if phrased that way through clenched teeth while pointing a shotgun at the offending party.

他们的自由观念也存留下来并塑造了美国的政治:它看起来基本上是现代自由意志主义者/共和党版本的免于政府干涉的自由,特别是“滚出我的土地”这句话,尤其是这话以咬牙切齿的腔调说出,伴着指向入侵者的霰弹枪的时候。

III.

This is all interesting as history and doubly interesting as anthropology, but what relevance does it have for later American history and the present day?

这些从历史学上来说,很有意思,从人类学角度来说,更有意思。但是这些和美国之后的历史以及今天又什么关系吗?

One of my reasons reading this book was to see whether the link between Americans’ political opinions and a bunch of their other cultural/religious/social traits (

a “Blue Tribe” and “Red Tribe”) was related to the immigration patterns it describes. I’m leaning towards “probably”, but there’s a lot of work to be done in explaining how the split among these four cultures led to a split among two cultures in the modern day, and with little help from the book itself I am going to have to resort to total unfounded speculation.

我读这本书的理由之一,是想看看美国政治观点和一系列文化/宗教/社会特质(“红部落”和“蓝部落”)是否和该书描述的移民模式相关。我倾向“很可能”这一结论,但是还需要大量的工作来解释这四种文化之分裂是如何导致今日的两种文化之分裂,而且接下来我将要不依赖这本书的帮助,诉诸未经验证的大胆猜想。

But the simplest explanation – that the Puritans and Quakers merged into one group (“progressives”, “Blue Tribe”, “educated coastal elites”) and the Virginians and Borderers into another (“conservatives”, “Red Tribe”, “rednecks”) – has a lot going for it.

然而最简单的解释有很大的说服力——清教徒和贵格会融合成了一个团体(“进步派”,“蓝部落”,“受过教育的东西岸精英”),而弗吉尼亚人和边民则汇聚成另一个(“保守派”,“红部落”,“红脖子”)。

Many conservatives I read like to push the theory that modern progressivism is descended from the utopian Protestant experiments of early America – Puritanism and Quakerism – and that the civil war represents “Massachusetts’ conquest of America”. I always found this lacking in rigor: Puritanism and Quakerism are sufficiently different that positing a combination of them probably needs more intellectual work than just gesturing at “you know, that Puritan/Quaker thing”.

我所读到的很多保守派喜欢这一理论:现代进步主义来自于早期乌托邦式的新教实验——清教主义和贵格主义——而内战则代表“‘马萨诸塞’”征服了美国”。我总是发现这个说法缺乏严谨:清教主义和贵格主义有很大的不同,把他们合并起来很可能需要更多的智力工作,而不是仅仅陈述“你知道的,清教徒/贵格会的那套”。

But the idea of a Puritan New England and a Quaker-(ish) Pennsylvania gradually blending together into a generic “North” seems plausible, especially given the high levels of interbreeding between the two (some of our more progressive Presidents, including Abraham Lincoln, were literally half-Puritan and half-Quaker).

但是一个清教徒的新英格兰和一个贵格会的宾夕法尼亚逐渐融合在一起,被统称为“北方”,这一说法似乎有道理,尤其是考虑到两个群体之间很高的通婚率(我们一些更偏进步派的总统,包括亚伯拉罕·林肯,实际上是半清教徒半贵格会血统)。

Such a merge would combine the Puritan emphasis on moral reform, education, and a well-ordered society with the Quaker doctrine of niceness, tolerance, religious pluralism, individual conscience, and the Inner Light. It seems kind of unfair to just mix-and-match the most modern elements of each and declare that this proves they caused modernity, but there’s no reason that

couldn’t have happened.

这种融合把清教徒对道德改革、教育和有序社会的强调,以及贵格会友善、容忍、宗教多元、个人良心和内在灵性之光的教义结合了起来。把两个宗派最现代化的元素混合对应起来,然后宣称这证明了他们导致了现代性,这似乎有点不公平,但是没有理由否定,这可能发生。

The idea of Cavaliers and Borderers combining to form modern conservativism is buoyed by modern conservativism’s obvious Border influences, but complicated by its lack of much that is recognizably Cavalier – the Republican Party is hardly marked by its support for a hereditary aristocracy of gentlemen.

骑士党和边民结合形成了现代保守主义这一看法,被现代保守主义明显受边民影响所支持。但更复杂的是,它缺乏可以被辨认为骑士党文化的成分——共和党在支持绅士们的世袭贵族政治方面并不突出。

Here I have to admit that I don’t know as much about Southern history as I’d like. In particular, how were places like Alabama, Mississippi, et cetera settled? Most sources I can find suggest they were set up along the Virginia model of plantation-owning aristocrats, but if that’s true how did the modern populations come to so embody Fischer’s description of Borderers? In particular, why are they

so Southern Baptist and

not very Anglican?

这里我不得不承认,我所知的南方历史,并不如我渴望的那么多。特别是,像阿拉巴马,密西西比这些地方是如何被开发的?我所找到的大部分资料都暗示,他们是按照弗吉尼亚那种拥有种植园的贵族模式发展,但是如果这是真的,为何现代这片土地上的人口和Fischer描述的边民如此相似?特别是,为什么他们如此倾向于南方浸信会,而不是国教会?

And what happened to all of those indentured servants the Cavaliers brought over after slavery put them out of business? What happened to that whole culture after the Civil War destroyed the plantation system? My

guess is going to be that the indentured servants and the Borderer population mixed pretty thoroughly, and that this stratum was hanging around providing a majority of the white bodies in the South while the plantation owners were hogging the limelight – but I just don’t know.

而所有那些骑士党带来的契约仆人在被奴隶取代而不再做仆人后,又经历了什么?在内战毁灭了南方种植园系统后,整个文化经历了什么?我的猜想是契约仆人和边民人口深度融合,而这个阶层蔓延开来,构成了南方白人的主体,而与此同时种植园主们则吸引了太多关注——但是我就是不知道。

A quick argument that I’m not totally making all of this up:

以下的简易论证并非纯属编造:

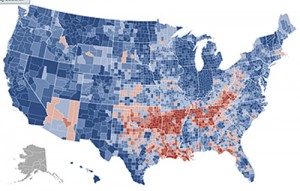

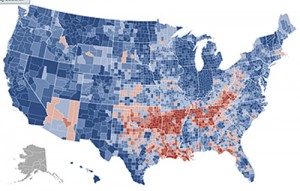

This is a map of voting patterns by county in the 2012 Presidential election. The blue areas in the South carefully track the so-called “black belt” of majority African-American areas. The ones in the Midwest are mostly big cities. Aside from those, the only people who vote Democrat are New England (very solidly!) and the Delaware Valley region of Pennsylvania.

这是2012年总统大选在郡层面的投票模式的地图。蓝色区域在南方精确地分布在大量非裔美国人聚居的所谓“黑带”上。在中西部的蓝色基本上是大城市。除了这些,选民主党的人只有新英格兰人(支持度很高!)和宾州德拉威尔河谷地区。

In fact, you can easily see the distinction between the Delaware Valley settled by Quakers in the east, and the backcountry area settled by Borderers in the west. Even the book’s footnote about how a few Borderers settled in the mountains of New Hampshire is associated with a few spots of red in the mountains of New Hampshire ruining an otherwise near-perfect Democratic sweep of the north.

事实上,你能一眼看出,贵格会开拓的东部德拉威尔河谷和边民开拓的西部区域之间的区别。即便是书中脚注提到的少量边民移居新罕布尔州群山也能对应图中新罕布尔州群山中的几个红点,如果不是这几个红点,民主党在北方就拥有了完美的全胜。

One anomaly in this story is a kind of linear distribution of blue across southern Michigan, too big to be explained solely by the blacks of Detroit. But a quick look at Wikipedia’s

History of Michigan finds:

这个故事中的一个异常就是在南密歇根存在一种线性分布的蓝色,面积太大,不能仅用底特律的黑人来解释。但是快速浏览维基百科上密歇根的历史条目就会发现:

In the 1820s and 1830s migrants from New England began moving to what is now Michigan in large numbers (though there was a trickle of New England settlers who arrived before this date). These were “Yankee” settlers, that is to say they were descended from the English Puritans who settled New England during the colonial era….Due to the prevalence of New Englanders and New England transplants from upstate New York, Michigan was very culturally contiguous with early New England culture for much of its early history…The amount with which the New England Yankee population predominated made Michigan unique among frontier states in the antebellum period. Due to this heritage Michigan was on the forefront of the antislavery crusade and reforms during the 1840s and 1850s.

在1820年代到1830年代,来自新英格兰的移民大量移居到今日的密歇根(虽然有少量新英格兰开拓者在之前就移居此地)。这些是“扬基”开拓者,这意味着他们是在殖民地时期住在新英格兰的英国清教徒的后裔……因为新英格兰人众多,以及从纽约上州移入的新英格兰人,在它早期历史的相当长时间,密歇根在文化上和早期新英格兰文化很相近……新英格兰扬基人口的庞大数量使得密歇根在内战前时期边疆州当中与众不同。因为这种传统,密歇根站在1840年代和1850年代的废奴十字军和改革的前列。

Alhough I can’t find proof of this specifically, I know that Michigan was settled from the south up, and I suspect that these New England settlers concentrated in the southern regions and that the north was settled by a more diverse group of whites who lacked the New England connection.

虽然我不能发现专门的证据,我知道密歇根是从南方被开拓的,我怀疑新英格兰开拓者集中于南部区域,而北部则被更多元的白人群体开拓,这些人缺乏和新英格兰地区的联系。

Here’s something else cool. We can’t track Borderers directly because there’s no “Borderer” or “Scots-Irish” option on the US census. But

Albion’s Seed points out that the Borderers were uniquely likely to identify as just “American” and deliberately forgot their past ancestry as fast as they could.

还有更有趣的发现。我们不能直接跟踪边民,因为在美国人口普查中没有“边民”或者“苏格兰人-爱尔兰人”的选项。但是《阿尔比安的种子》一书指出,边民特别倾向于自我认同为“美国人”,并故意尽快忘记自己过去的先祖。

Meanwhile, when the census asks an ethnicity question about where your ancestors came from, every year some people will stubbornly ignore the point of the question and put down “America” (no, this does not track the distribution of Native American population). Here’s a map of so-called “unhyphenated Americans”, taken from

this site:

同时,当普查问及关于你先祖来自何处的族裔问题时,每年都有一些人顽固的忽略这一问题的目的,而填上“美国”(不,这并不能代表印第安人的分布)。下面是所谓的“纯粹的美国人”的地图,来自这个网站。

We see a strong focus on the Appalachian Mountains, especially West Virginia, Tennesee, and Kentucky, bleeding into the rest of the South. Aside from west Pennsylvania, this is very close to where we would expect to find the Borderers. Could these be the same groups?

我们看到了该人群在阿巴拉契亚山脉区域有很高的密度,尤其是西弗吉尼亚,田纳西,和肯塔基,延伸到南方其他地区。除了西宾夕法尼亚之外,这和我们预期能发现边民的地区非常接近。这些可能是相同的人群吗?

Meanwhile, here is a map of where Obama underperformed the usual Democratic vote

worst in 2008:

同时,这里还有奥巴马在08年民主党选举中表现最差的地区的一张地图:

These maps are small and lossy, and surely unhyphenatedness is not an

exact proxy for Border ancestry – but they are nevertheless intriguing. You may also be interested in the Washington Post’s correlation between

distribution of unhyphenated Americans and Trump voters, or the Atlantic’s article on

Trump and Borderers.

这些地图也许小且模糊,而且纯种美国人认同也不是边民先祖的精确表征——但是它们仍然十分吸引人。你也许会对《华盛顿邮报》在纯种美国人分布和川普支持者之间相关性的报道感兴趣,还有《大西洋月刊》关于川普和边民的文章。

If I’m going to map these cultural affiliations to ancestry, do I have to walk back on my previous theory that they are

related to class? Maybe I should. But I also think we can posit complicated interactions between these ideas. Consider for example the interaction between race and class; a black person with a white-sounding name, who speaks with a white-sounding accent, and who adopts white culture (eg listens to classical music, wears business suits) is far more likely to seem upper-class than a black person with a black-sounding name, a black accent, and black cultural preferences; a white person who seems black in some way (listens to hip-hop, wears baggy clothes) is more likely to seem lower-class. This doesn’t mean race and class are exactly the same thing, but it does mean that some races get stereotyped as upper-class and others as lower-class, and that people’s racial identifiers may change based on where they are in the class structure.

如果我把这些文化偏好对应到祖先谱系,我是否也不得不回到我之前的理论上,即这些和阶层有关?也许我应该这么做。但是我也认为我们应该注意这些看法之间的交互作用。比如考虑一下种族和阶层的交互关系;一个黑人带着一个白人式的名字,带白人口音,适应了白人文化(比如听古典音乐,穿西装),则比取黑人名、带黑人口音、偏好黑人文化的黑人更可能是上等阶级;一个某方面像黑人的白人(听嘻哈,穿松垮的衣服)则更可能属于底层。这并不是说种族和阶层完全是一码事,但是这说明一些族群给人的固定印象是上层,另一些是底层,而基于人们在阶层结构中位置,人们的和种族相关的特征可能会变化。

I think something similar is probably going on with these forms of ancestry. The education system is probably dominated by descendents of New Englanders and Pennsylvanians; they had an opportunity to influence the culture of academia and the educated classes more generally, they took it, and now anybody of any background who makes it into that world is going to be socialized according to their rules. Likewise, people in poorer and more rural environments will be surrounded by people of Borderer ancestry and acculturated by Borderer cultural products and end up a little more like that group. As a result, ethnic markers have turned into and merged with class markers in complicated ways.

我认为族裔血统的构成中,很可能发生了相似的事情。教育系统很可能被新英格兰人和宾夕法尼亚人把持,他们更有机会普遍地影响学术界的文化和受教育阶层,他们把握了这个机会,现在任何背景的人,要进入他们的世界,都会按照他们的规则被社会化。相似的,更穷和更乡村化的人,被边民的先祖和边民文化的产物包围,最终变得有点像这个群体。结果,族裔标志以种种复杂的方式转化成了阶层标志并与之融合。

Indeed, some kind of acculturation process has to have been going on, since most of the people in these areas today are not the descendents of the original settlers. But such a process seems very likely. Just to take an example, most of the Jews I know (including my own family) came into the country via New York, live somewhere on the coast, and have very Blue Tribe values. But Southern Jews believed in the Confederacy as strongly as any Virginian – see for example

Judah Benjamin. And

Barry Goldwater, a half-Jew raised in Arizona, invented the modern version of conservativism that seems closest to some Borderer beliefs.

的确,某种同化过程一定发生过,因为这些地区今天的大部分人并不是初代开拓者的后代。但是这样一个过程很可能发生。仅举一个例子,大部分我所认识的犹太人(包括我自己的家庭),从纽约来到这个国家,生活在靠海岸的某处,拥有蓝色的价值观。但是南方犹太人曾和任何弗吉尼亚人一样,相信南部邦联——可以参考Judah Benjamin的例子。而且Barry Goldwater,一个长在亚利桑那的半血犹太人,发明了现代版本的保守主义,其观点看起来最接近一些边民信仰。

All of this is very speculative, with some obvious flaws. What do we make of other countries like Britain or Germany with superficially similar splits but very different histories? Why should Puritans lose their religion and sexual prudery, but keep their interest in moralistic reform? There are whole heaps of questions like these.

所有这些都是很大胆的假设,带有一些明显的缺陷。对于英国或者德国,这些国家表面上有类似的分裂,但是有很不同的历史,我们如何来解释呢?为什么清教徒失去了他们的宗教和在性上的规矩,但是仍然在道德改革上保持兴趣?还有一大堆类似的问题。

But look. Before I had any idea about any of this, I wrote that American society seems divided into two strata, one of which is marked by emphasis on education, interest in moral reforms, racial tolerance, low teenage pregnancy, academic/financial jobs, and Democratic party affiliation, and furthermore that this group was centered in the North.

但是看看,在我有这些想法之前,我就曾写道美国社会看来被分裂成两层,其中之一有以下特征:重视教育、道德变革、种族宽容,很低的未成年怀孕率,学术和财经工作,以及支持民主党,而且这个群体以北方为中心。

Meanwhile, now I learn that the North was settled by two groups that when combined have emphasis on education, interest in moral reforms, racial tolerance, low teenage pregnancy, an academic and mercantile history, and were the heartland of the historical Whigs and Republicans who preceded the modern Democratic Party.

同时,我现在知道了北方曾被两个团体所开拓,两个群体结合起来,拥有以下特征:重视教育、道德变革、种族宽容,很低的未成年怀孕率 ,具有学术和商业历史,而且是历史上辉格党和共和党(后来的地位被现代的民主党取代)的核心地域。

And I wrote about another stratum centered in the South marked by poor education, gun culture, culture of violence, xenophobia, high teenage pregnancy, militarism, patriotism, country western music, and support for the Republican Party. And now I learn that the South was settled by a group noted even in the 1700s for its poor education, gun culture, culture of violence, xenophobia, high premarital pregnancy, militarism, patriotism, accent exactly like the modern country western accent, and support for the Democratic-Republicans who preceded the modern Republican Party.

我还写到过另一个集中于南方的阶层,它以教育贫乏,枪文化,暴力文化,排外,高未成年人怀孕率,军国主义,爱国主义,西部乡村音乐,和支持共和党为特征。现在我知道,开拓南方的群体,在18世纪就以教育的贫乏, 枪文化,暴力文化,排外,高未成年人怀孕率,尚武精神,爱国主义,接近现代西部乡村的口音,以及支持民主-共和党为特征(后来地位被现代的共和党取代)。

If this is true, I think it paints a very pessimistic world-view. The “iceberg model” of culture argues that apart from the surface cultural features we all recognize like language, clothing, and food, there are deeper levels of culture that determine the features and institutions of a people: whether they are progressive or traditional, peaceful or warlike, mercantile or self-contained.

如果这是真的,我认为这给出了一个非常悲观的世界图景。文化的“冰山模型”认为,撇开我们都能识别的文化表面特征,例如语言、衣着、和食物,存在更深层次的文化,它们决定了上述特征和人们的制度:决定他们是进步的还是传统的,和平的还是好战的,爱经商的还是自给自足的。

We grudgingly acknowledge these features when we admit that maybe making the Middle East exactly like America in every way is more of a long-term project than something that will happen as soon as we kick out the latest dictator and get treated as liberators. Part of us may still want to believe that pure reason is the universal solvent, that those Afghans will come around once they realize that being a secular liberal democracy is obviously great.

当我们承认也许让中东在每一方面都变成和美国一样是一个长期过程,而不是如我们把最近的独裁者赶下台,像解放者般被接待那么快,我们就是在勉强承认这些文化特征的存在。我们中的部分人还想相信纯粹理性是普遍适用的答案,只要阿富汗人意识到一个世俗化的自由主义的民主制度明显很棒,他们就会觉醒。

But we keep having deep culture shoved in our face again and again, and we don’t know how to get rid of it. This has led to reasonable speculation that some aspects of it might even be genetic – something which would explain a lot, though not its ability to acculturate recent arrivals.

但是我们已经一而再地被深层文化打脸,我们不知道如何摆脱它。这导致了合理的猜想,深层文化的某方面可能是遗传性的——这可以解释很多事情,虽然这个因素不能解释其同化最近的新来者的能力。

This is a hard pill to swallow even when we’re talking about Afghanistan. But it becomes doubly unpleasant when we think about it in the sense of our neighbors and fellow citizens in a modern democracy. What, after all, is the point? A democracy made up of 49% extremely liberal Americans and 51% fundamentalist Taliban Afghans would be something very different from the democratic ideal; even if occasionally a super-charismatic American candidate could win over enough marginal Afghans to take power, there’s none of the give-and-take, none of the competition within the marketplace of ideas, that makes democracy so attractive. Just two groups competing to dominate one another, with the fact that the competition is peaceful being at best a consolation prize.

即便我们讨论的是阿富汗,这也是一枚难以下咽的药丸。但如果我们从现代民主制中我们的邻舍和公民同胞的角度来考虑这个问题时,难受程度又要翻倍。这到底有什么意义?一个由49%的极端自由派的美国人和51%的基本教义派的阿富汗塔利班组成的民主制恐怕和民主典范非常不同;即使有时,一个很有人格魅力的美国候选人能赢得足够的阿富汗人摇摆票,获得权力,这里也没有讨价还价,没有思想市场的竞争,而正是这些因素才使得民主制如此有吸引力。只剩两个团体相互竞争来统治对方,事实上,如果竞争是和平的,就已经是谢天谢地了。

If America is best explained as a Puritan-Quaker culture locked in a death-match with a Cavalier-Borderer culture, with all of the appeals to freedom and equality and order and justice being just so many epiphenomena – well, I’m not sure what to do with that information.

如果美国可以很好地被解释成一种清教徒-贵格会文化,和一种骑士党-边民文化锁在一起的拼死对决,并且所有对自由,平等,秩序,正义的呼求仅是众多附带现象——那么我不确定该如何处理这个信息。

Push it under the rug? Say “Well, my culture is better, so I intend to do as good a job dominating yours as possible?” Agree that We Are Very Different Yet In The End All The Same And So Must Seek Common Ground? Start researching genetic engineering? Maybe secede?

把它藏在桌布下?说“好,我的文化更好,所以我打算竭尽全力做做好事,来统治你?”同意我们是非常不同的,但最终我们会变得一样,所以我们必须寻求共同立场?开始研究基因工程?也许独立分裂?

I’m not a Trump fan much more than I’m an Osama bin Laden fan; if somehow Osama ended up being elected President, should I start thinking “Maybe that time we made a country that was 49% people like me and 51% members of the Taliban –