Why Do Americans Stink at Math?

为什么美国人数学这么差?

作者:Elizabeth Green @ 2014-7-23

译者:沈沉(@你在何地-sxy)

校对:带菜刀的诗人(@带菜刀的诗人_),慕白(@李凤阳他说)

来源:The New York Times,

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/27/magazine/why-do-americans-stink-at-math.html

【照片插图来自于Andrew B. Myers 道具师:Randi Brookman Harris。计算器图标来自于Tim Boelaars】

When Akihiko Takahashi was a junior in college in 1978, he was like most of the other students at his university in suburban Tokyo. He had a vague sense of wanting to accomplish something but no clue what that something should be. But that spring he met a man who would become his mentor, and this relationship set the course of his entire career.

1978年,高桥昭彦还是东京郊外一所大学的三年级学生,和其他大多数同学没什么两样。他模模糊糊觉得自己想要做点什么,但对于到底该做什么却毫无头绪。但那年春天他遇到了他后来的导师,就此确定了他此后全部事业的方向。

Takeshi Matsuyama was an elementary-school teacher, but like a small number of instructors in Japan, he taught not just young children but also college students who wanted to become teachers. At the university-affiliated elementary school where Matsuyama taught, he turned his classroom into a kind of laboratory, concocting and trying out new teaching ideas. When Takahashi met him, Matsuyama was in the middle of his boldest experiment yet — revolutionizing the way students learned math by radically changing the way teachers taught it.

松山武士是位小学教师,不过跟日本的一小批类似教员一样,他不止教小孩子,也给想当教师的大学生上课。松山武士任教于这所大学的附属小学。他把自己的课堂改造成了一个实验室,策划并尝试各种教学新理念。高桥昭彦刚认识他时,松山武士正在进行一项空前大胆的试验——通过改变教师的教学方法,全面革新学生们的数学学习方法。

Instead of having students memorize and then practice endless lists of equations — which Takahashi remembered from his own days in school — Matsuyama taught his college students to encourage passionate discussions among children so they would come to uncover math’s procedures, properties and proofs for themselves.

松山武士并不要求学生背诵并练习无穷无尽的公式——松山武士自己念书时就记了很多方程式——,而是教育他的大学生,应当鼓励孩子们激烈讨论,从而能自行找出数学中的解题流程、性质和证明。

One day, for example, the young students would derive the formula for finding the area of a rectangle; the next, they would use what they learned to do the same for parallelograms. Taught this new way, math itself seemed transformed. It was not dull misery but challenging, stimulating and even fun.

比如,学生们某天可能会推导出矩形的面积公式,那么第二天他们就可以用已经学到的东西去推导平行四边形的面积公式。以这种新方法教学,数学这门课似乎完全不同了。它不再枯燥痛苦,而是富有挑战性、刺激性,甚至很有趣。

【照片插图来自于Andrew B. Myers 道具师:Randi Brookman Harris】

Takahashi quickly became a convert. He discovered that these ideas came from reformers in the United States, and he dedicated himself to learning to teach like an American. Over the next 12 years, as the Japanese educational system embraced this more vibrant approach to math, Takahashi taught first through sixth grade.

高桥昭彦很快就信服了。他发现这些理念最早是由美国的一些改革者提出来的,于是致力于像美国人一样教学。此后12年里,日本的教育体系采纳了这一更富活力的数学教育方法,高桥昭彦则从一年级一直教到六年级。

Teaching, and thinking about teaching, was practically all he did. A quiet man with calm, smiling eyes, his passion for a new kind of math instruction could take his colleagues by surprise. “He looks very gentle and kind,” Kazuyuki Shirai, a fellow math teacher, told me through a translator. “But when he starts talking about math, everything changes.”

教育以及反思教育几乎就是他的全部活动。他安静沉稳,眼带笑意,对数学教学新方法的激情常令同事大吃一惊。数学教师白井一之通过翻译告诉我:“他看上去特别温和、特别友善。不过一旦说起数学,情况就全变了。”

Takahashi was especially enthralled with an American group called the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, or N.C.T.M., which published manifestoes throughout the 1980s, prescribing radical changes in the teaching of math. Spending late nights at school, Takahashi read every one. Like many professionals in Japan, teachers often said they did their work in the name of their mentor. It was as if Takahashi bore two influences: Matsuyama and the American reformers.

高桥昭彦对一个叫全美数学教师委员会(NCTM)的美国机构特别着迷。1980年代,该委员会持续发表宣言,建议对数学教学进行彻底改革。高桥昭彦在学校熬夜阅读了所有这些宣言。跟日本的许多专业人士一样,日本教师常说自己所做的都应归于其导师名下。高桥昭彦身上似乎体现了两种影响:一种来自松山武士,一种来自美国的改革者。

Takahashi, who is 58, became one of his country’s leading math teachers, once attracting 1,000 observers to a public lesson. He participated in a classroom equivalent of “Iron Chef,” the popular Japanese television show.

高桥昭彦现年58岁,已是日本数学教师的领军人物之一。他的一次公开课曾吸引了1000人旁听。他还参加了一个类似于“铁人料理”的课堂【

译注:铁人料理是富士电视台的一档烹饪节目,每集由不同的挑战者选择挑战三位“铁厨”中的一位,用一小时来烹制围绕该集主题材料的菜式】。

But in 1991, when he got the opportunity to take a new job in America, teaching at a school run by the Japanese Education Ministry for expats in Chicago, he did not hesitate. With his wife, a graphic designer, he left his friends, family, colleagues — everything he knew — and moved to the United States, eager to be at the center of the new math.

不过,当他1991年有机会到美国工作,在一所由文部省为芝加哥日侨办的学校教课时,他没有犹豫。带着自己的平面设计师妻子,他辞别了朋友、家人、同事以及他所熟知的一切,移居美国,热切地想要走进新数学的中心。

As soon as he arrived, he started spending his days off visiting American schools. One of the first math classes he observed gave him such a jolt that he assumed there must have been some kind of mistake. The class looked exactly like his own memories of school. “I thought, Well, that’s only this class,” Takahashi said.

一到美国,他就开始利用空闲时间走访各学校。最早旁听到的其中一门数学课让他无比震惊,以至于他只能假定一定有什么地方出错了。这堂数学课看起来跟他念书时的记忆一模一样。“我想,呃,只是这堂课如此而已”,高桥昭彦说。

But the next class looked like the first, and so did the next and the one after that. The Americans might have invented the world’s best methods for teaching math to children, but it was difficult to find anyone actually using them.

但接下来第二堂课依然如此,接下来、再接下来都是这样。美国人或许发明了世界上最好的针对孩子的数学教学方法,但很难找到有人真的在实践这种方法。

It wasn’t the first time that Americans had dreamed up a better way to teach math and then failed to implement it. The same pattern played out in the 1960s, when schools gripped by a post-Sputnik inferiority complex unveiled an ambitious “new math,” only to find, a few years later, that nothing actually changed.

美国人构想出数学教学的改良方法却没能实施,这已不是第一次了。1960年代出现过同样的事,受“后斯普特尼克自卑情结”影响【

译注:斯普特尼克一号(Sputnik 1)是世界上第一颗人造卫星,前苏联造,是冷战时期美苏太空竞争、科技竞争的标志之一】,美国学校公布了一项雄心勃勃的“新数学”计划,数年之后却发现什么都未曾改变过。

In fact, efforts to introduce a better way of teaching math stretch back to the 1800s. The story is the same every time: a big, excited push, followed by mass confusion and then a return to conventional practices.

事实上,引入更好方法改进数学教学的种种努力可以追溯到1800年代。每一次的故事都一模一样:一股庞大、兴奋的劲头之后,出现了大量混乱,然后又回归到老办法。

The trouble always starts when teachers are told to put innovative ideas into practice without much guidance on how to do it. In the hands of unprepared teachers, the reforms turn to nonsense, perplexing students more than helping them.

一旦教师们被要求将创新理念付诸实践,但却不在如何去做这方面为他们提供多少指导,麻烦就总会出现。在毫无准备的教师手中,改革变成了胡闹,学生得到的困惑费解多于助益。

One 1965 Peanuts cartoon depicts the young blond-haired Sally struggling to understand her new-math assignment: “Sets . . . one to one matching . . . equivalent sets . . . sets of one . . . sets of two . . . renaming two. . . .” After persisting for three valiant frames, she throws back her head and bursts into tears: “All I want to know is, how much is two and two?”

1965年《花生》(Peanuts)上的一则漫画就曾描绘了,金发小女孩萨丽如何绞尽脑汁去理解她的“新数学”功课:“集合……单射……相等的集合……1的集合……2的集合……对2进行重命名……”。在顽强坚持了三格漫画之后,她仰头大哭:“我就想知道2加2等于几?”

Today the frustrating descent from good intentions to tears is playing out once again, as states across the country carry out the latest wave of math reforms: the Common Core.

今天,这种令人揪心的好心变泪水的场景正在重演。美国各州纷纷着手实施最新一轮数学改革,采纳“公共核心”(Common Core)。

A new set of academic standards developed to replace states’ individually designed learning goals, the Common Core math standards are like earlier math reforms, only further refined and more ambitious.

公共核心数学标准是一套新的教学标准,旨在替代各州先前自行设定的学习目标。这套标准与之前的数学改革相似,只是更为细致,抱负更大。

Whereas previous movements found teachers haphazardly, through organizations like Takahashi’s beloved N.C.T.M. math-teacher group, the Common Core has a broader reach.

此前的改革行动只是偶尔有一些教师参加,而相比之下,通过像NCTM这种高桥昭彦所钟爱的数学教师团体,“公共核心”影响范围更广。

A group of governors and education chiefs from 48 states initiated the writing of the standards, for both math and language arts, in 2009. The same year, the Obama administration encouraged the idea, making the adoption of rigorous “common standards” a criterion for receiving a portion of the more than $4 billion in Race to the Top grants. Forty-three states have adopted the standards.

2009年,来自48个州的州长和教育官员发起制定了有关数学和语言技能的公共核心标准。同年,奥巴马政府支持了这一理念,将严格采纳“公共标准”确定为能否从40多亿美元的“力争上游”(Race to the Top)专款中分得一杯羹的评判准则。现在,已有43个州采纳了这一标准。

The opportunity to change the way math is taught, as N.C.T.M. declared in its endorsement of the Common Core standards, is “unprecedented.” And yet, once again, the reforms have arrived without any good system for helping teachers learn to teach them.

正如NCTM在其对公共核心标准的公开支持中所宣称的,采纳这一标准所带来的数学教学革新机会“前所未见”。然而,又一次,能够帮助教师们学会如何教授这一标准的良好体系并没有随着改革一起到来。

Responding to a recent survey by Education Week, teachers said they had typically spent fewer than four days in Common Core training, and that included training for the language-arts standards as well as the math.

在回答《教育周刊》的调查提问时,教师们说,他们所接受的“公共核心”培训普遍不超过4天,而且还是语言技能标准和数学标准培训都包含在内。

Carefully taught, the assignments can help make math more concrete. Students don’t just memorize their times tables and addition facts but also understand how arithmetic works and how to apply it to real-life situations. But in practice, most teachers are unprepared and children are baffled, leaving parents furious.

如果精心教授,新功课能让数学更为具体实际。学生们不仅仅会背诵乘法表和加法口诀,还能理解算术的原理,并能将其应用于实际生活。但事实上,大部分教师都毫无准备,孩子们被搞得一头雾水,家长们则怒气冲冲。

The comedian Louis C.K. parodied his daughters’ homework in an appearance on “The Late Show With David Letterman”: “It’s like, Bill has three goldfish. He buys two more. How many dogs live in London?”

喜剧演员Louis C. K. 在参加《大卫·莱特曼深夜秀》时曾搞笑模仿他女儿的作业:“比如,比尔有三条金鱼。他又买了两条。请问伦敦有多少条狗?”

The inadequate implementation can make math reforms seem like the most absurd form of policy change — one that creates a whole new problem to solve. Why try something we’ve failed at a half-dozen times before, only to watch it backfire? Just four years after the standards were first released, this argument has gained traction on both sides of the aisle.

实施不到位,可能会让数学课改革变成一次将会制造出有待解决的全新麻烦的那种政策变动,愚蠢之极。为什么要去做那些我们已屡试屡败的事呢?就为了弄巧成拙?标准发布才4年,左右两翼就都已经开始这么想了。

Since March, four Republican governors have opposed the standards. In New York, a Republican candidate is trying to establish another ballot line, called Stop Common Core, for the November gubernatorial election. On the left, meanwhile, teachers’ unions in Chicago and New York have opposed the reforms.

3月以来,已有4位共和党州长反对该标准。纽约的一位共和党候选人正在推动为11月的州长选举设立一个投票选项栏(ballot line),就叫“停止公共核心”【

编注:ballot line是合并选举制度(electoral fusion)中的一种投票安排,一个ballot line在选票上单独占据一栏,但多个ballot line可以对应同一位候选人,这一安排改善了小党派和单议题政党参与单一选区制下竞选活动的机会,不然的话,单一选区制通常会造成两党寡头垄断。这项制度在19世纪晚期曾流行于美国各州,后来逐渐被各州禁止,目前尚有8个州采用,包括纽约州】。在左翼那边,芝加哥和纽约的教师工会也已对改革表示反对。

The fact that countries like Japan have implemented a similar approach with great success offers little consolation when the results here seem so dreadful. Americans might have written the new math, but maybe we simply aren’t suited to it. “By God,” wrote Erick Erickson, editor of the website RedState, in an anti-Common Core attack, is it such “a horrific idea that we might teach math the way math has always been taught.”

结局如此糟糕,以至于日本等国实施类似办法而取得的巨大成功都于事无补。美国人也许制定了“新数学”标准,但它可能确实不适合我们。在一篇反公共核心的批评文章中,RedState网站的编辑Erick Erickson写道:“神啊,以历来如此的数学教学方式教数学,这个想法难道就那么可怕吗?”

The new math of the ‘60s, the

new new math of the ‘80s and today’s Common Core math all stem from the idea that the traditional way of teaching math simply does not work. As a nation, we suffer from an ailment that John Allen Paulos, a Temple University math professor and an author, calls innumeracy — the mathematical equivalent of not being able to read.

60年代的新数学,80年代的新新数学,以及当下的公共核心数学,都源于同一个观念,即传统的数学教学方式就是行不通。我们的国民染上了一种病,天普大学数学教授和作家John Allen Paulos称之为数盲——数学方面的文盲。

On national tests, nearly two-thirds of fourth graders and eighth graders are not proficient in math. More than half of fourth graders taking the 2013 National Assessment of Educational Progress could not accurately read the temperature on a neatly drawn thermometer. (They did not understand that each hash mark represented two degrees rather than one, leading many students to mistake 46 degrees for 43 degrees.)

全国性考试显示,将近三分之二的四年级和八年级学生数学不熟练。在2013年“国家教育进步评价”中,过半数的四年级学生无法准确认读描画清晰的温度计上的读数(他们不知道每个小刻度代表2度而非1度,因此许多学生误将46度认读成了43度)。

On the same multiple-choice test, three-quarters of fourth graders could not translate a simple word problem about a girl who sold 15 cups of lemonade on Saturday and twice as many on Sunday into the expression “15 + (2×15).” Even in Massachusetts, one of the country’s highest-performing states, math students are more than two years behind their counterparts in Shanghai.

同样在上述选择题测试中,四分之三的四年级学生无法将“小女孩周六卖了15杯柠檬汁,周日卖了周六的2倍”这种简单的文字问题转换为“15+(2X15)”这一表达式。即使在马萨诸塞这种全国表现最好的州,数学课学生进度也落后于上海同年级学生两年以上。

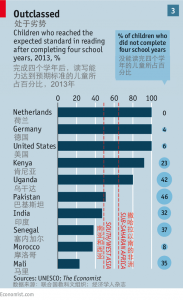

Adulthood does not alleviate our quantitative deficiency. A 2012 study comparing 16-to-65-year-olds in 20 countries found that Americans rank in the bottom five in numeracy. On a scale of 1 to 5, 29 percent of them scored at Level 1 or below, meaning they could do basic arithmetic but not computations requiring two or more steps.

成年并未能缓解我们的数学缺陷。2012年一项针对20个国家的16-65岁人口的比较研究发现,美国人的算术能力排在最后5名。按1-5的等级衡量,29%的美国人得分在等级1或更低,表明他们会做基本的算术,但碰到两步或两步以上的运算就不会了。

One study that examined medical prescriptions gone awry found that 17 percent of errors were caused by math mistakes on the part of doctors or pharmacists. A survey found that three-quarters of doctors inaccurately estimated the rates of death and major complications associated with common medical procedures, even in their own specialty areas.

针对医药处方差错的一项分析研究发现,17%的失误源于医生或药剂师的数学错误。一项调查发现,四分之三的医生对于常见手术的死亡率和主要并发症发病率存在错误估计,即使在他们自身的专业领域也不例外。

One of the most vivid arithmetic failings displayed by Americans occurred in the early 1980s, when the A&W restaurant chain released a new hamburger to rival the McDonald’s Quarter Pounder. With a third-pound of beef, the A&W burger had more meat than the Quarter Pounder; in taste tests, customers preferred A&W’s burger. And it was less expensive. A lavish A&W television and radio marketing campaign cited these benefits. Yet instead of leaping at the great value, customers snubbed it.

美国人数学缺陷的一次生动展示发生在1980年代初,当时A&W连锁快餐为与麦当劳的“1/4磅汉堡”竞争,推出了一种新汉堡,里面有1/3磅牛肉,比麦当劳的“1/4磅”要多。在品尝活动中,顾客也更喜欢A&W汉堡。而且它还更便宜。A&W在电视和广播上做了大量市场推广活动,宣传这些优点。然而对这样的超值之物,消费者并不买账,反而是冷落有加。

Only when the company held customer focus groups did it become clear why. The Third Pounder presented the American public with a test in fractions. And we failed. Misunderstanding the value of one-third, customers believed they were being overcharged. Why, they asked the researchers, should they pay the same amount for a third of a pound of meat as they did for a quarter-pound of meat at McDonald’s. The “4” in “¼,” larger than the “3” in “⅓,” led them astray.

直到A&W公司开展了消费者焦点组调研,事情的原因才搞清楚。“1/3磅汉堡”给美国公众出了道分数题,我们却没有答对。消费者误解了1/3的数值,认为这种汉堡价格过高。他们问调研人员,凭什么要他们为三分之一磅肉支付那么多钱,而同样的钱在麦当劳可以买到四分之一磅肉。“1/4”中的“4”大于“1/3”中的“3”,这导致他们理解错误。

But our innumeracy isn’t inevitable. In the 1970s and the 1980s, cognitive scientists studied a population known as the unschooled, people with little or no formal education. Observing workers at a Baltimore dairy factory in the ‘80s, the psychologist Sylvia Scribner noted that even basic tasks required an extensive amount of math.

但我们的数盲并非无可避免。在1970年代和1980年代,认知科学家对一个失学人群——即没有或几乎没有受过正式教育的人群——进行了研究。通过考察80年代巴尔的摩乳品厂的工人,心理学家Sylvia Scribner发现,即使最基本的工作也要求掌握大量数学。

For instance, many of the workers charged with loading quarts and gallons of milk into crates had no more than a sixth-grade education. But they were able to do math, in order to assemble their loads efficiently, that was “equivalent to shifting between different base systems of numbers.”

比如,负责将牛奶成夸脱成加仑地装入大货箱的工人,所受教育均不超过六年级。但为了高效装箱,他们能做数学,装箱“就相当于在不同的基本数字系统之间进行换算”。

Throughout these mental calculations, errors were “virtually nonexistent.” And yet when these workers were out sick and the dairy’s better-educated office workers filled in for them, productivity declined.

在这种心算过程中,“基本不存在”错误。而当这些工人因病休假,由乳品厂受过更好教育的办公室职员来顶缺时,生产率就会下降。

The unschooled may have been more capable of complex math than people who were specifically taught it, but in the context of school, they were stymied by math they already knew.

虽然相比受过特定教育的人来说,失学人群进行复杂数学运算的能力更强,但一旦处于学校环境中,他们却被他们其实已经掌握的数学问题难住了。

Studies of children in Brazil, who helped support their families by roaming the streets selling roasted peanuts and coconuts, showed that the children routinely solved complex problems in their heads to calculate a bill or make change. When cognitive scientists presented the children with the very same problem, however, this time with pen and paper, they stumbled.

在巴西,为贴补家用,很多小孩在大街上沿街贩卖烤花生和椰子。研究发现,这些孩子经常在脑子里默算复杂的账单和找零问题。但是,当认知科学家向他们提出同样的问题,让他们用笔和纸作答时,这些孩子就卡壳了。

A 12-year-old boy who accurately computed the price of four coconuts at 35 cruzeiros each was later given the problem on paper. Incorrectly using the multiplication method he was taught in school, he came up with the wrong answer.

有个12岁男孩,能准确算出4个单价为35克鲁塞罗【

译注:巴西旧币】的椰子的总价,但是同样的问题写在纸上时,他得出的却是一个错误的答数,因为他用错了学校里教的乘法。

Similarly, when Scribner gave her dairy workers tests using the language of math class, their scores averaged around 64 percent. The cognitive-science research suggested a startling cause of Americans’ innumeracy: school.

同样,当Scribner用数学课上用的语言对她考察的乳品厂工人进行测验时,他们的平均成绩大概是64分(总分100分)。认知科学研究表明,美国人患上数盲症的原因竟然是学校。

Most American math classes follow the same pattern, a ritualistic series of steps so ingrained that one researcher termed it a cultural script. Some teachers call the pattern “I, We, You.” After checking homework, teachers announce the day’s topic, demonstrating a new procedure: “Today, I’m going to show you how to divide a three-digit number by a two-digit number” (I).

大多数美国数学课程采用同样的模式,一系列程式化的步骤根深蒂固,有位研究者干脆称之为“训练脚本”。一些教师把这种模式叫做“我、我们、你”模式。检查完作业,教师们先宣布当日要讲的内容,展示一套新的解题流程:“今天,我来教你们怎么做三位数除以两位数的除法”(我)。

Then they lead the class in trying out a sample problem: “Let’s try out the steps for 242 ÷ 16” (We). Finally they let students work through similar problems on their own, usually by silently making their way through a work sheet: “Keep your eyes on your own paper!” (You).

然后他们就带领全班尝试解答例题:“我们来试试242÷16的解题步骤”(我们)。最后,他们让学生们自己去解决类似的题目,通常就是要他们安静地做一套练习题:“专心做自己的题!”(你们)。

By focusing only on procedures — “Draw a division house, put ‘242’ on the inside and ‘16’ on the outside, etc.” — and not on what the procedures mean, “I, We, You” turns school math into a sort of arbitrary process wholly divorced from the real world of numbers.

“我、我们、你”模式只关心解题流程——“画个除法小屋【

译注:即长除法竖式中的√符号】,把242放在里面,16放在外边,等等”,而不关心这些流程的意义,把课堂数学变成了一种独断的过程,与真实世界的数字完完全全不搭边。

Students learn not math but, in the words of one math educator, answer-getting. Instead of trying to convey, say, the essence of what it means to subtract fractions, teachers tell students to draw butterflies and multiply along the diagonal wings, add the antennas and finally reduce and simplify as needed.

用一位数学教育者的话说,学生们学的不是数学,而是解题。比如,教师们不是试图去传授做分数减法的实质意义,而是告诉学生们先画蝴蝶,然后将蝴蝶对角翅膀上的数字做乘法,再把两个触角上的数字做加法,最后,如果需要,再化简分数。

The answer-getting strategies may serve them well for a class period of practice problems, but after a week, they forget. And students often can’t figure out how to apply the strategy for a particular problem to new problems.

这种解题策略虽然能让学生们在上课期间把练习题做得很好,但一个星期之后,他们就会忘光。而且学生们还经常搞不清楚如何用这种针对个别问题的策略解决新问题。

How could you teach math in school that mirrors the way children learn it in the world? That was the challenge Magdalene Lampert set for herself in the 1980s, when she began teaching elementary-school math in Cambridge, Mass.

我们应该如何模仿孩子们在真实世界的学习方式来进行课堂数学教育呢?这就是玛达勒纳·兰珀特(Magdalene Lampert)在1980年代为自己设定的挑战,当时她刚开始在马萨诸塞的坎布里奇担任小学数学教师。

She grew up in Trenton, accompanying her father on his milk deliveries around town, solving the milk-related math problems he encountered. “Like, you know: If Mrs. Jones wants three quarts of this and Mrs. Smith, who lives next door, wants eight quarts, how many cases do you have to put on the truck?” Lampert, who is 67 years old, explained to me.

她在特伦顿长大,从小就随父亲一起在镇上派送牛奶,帮着父亲处理相关算术问题。“比如:琼斯先生要3夸脱这个,他隔壁的史密斯太太则要8夸脱,那么要往卡车上装几箱奶?”现年67岁的兰珀特这么跟我说。

She knew there must be a way to tap into what students already understood and then build on it. In her classroom, she replaced “I, We, You” with a structure you might call “You, Y’all, We.”

她深知必然存在一种方法,可以让我们利用学生们已经理解的东西,再在上面添砖加瓦。她在自己的课堂里抛弃了“我、我们、你”模式,采纳了一种可称为“你、你们、我们”的模式。

Rather than starting each lesson by introducing the main idea to be learned that day, she assigned a single “problem of the day,” designed to let students struggle toward it — first on their own (You), then in peer groups (Y’all) and finally as a whole class (We).

她的每节课并不从介绍当日要学的主要内容开始,而是布置一个“每日一问”。设计这个问题,是为了让学生们努力去解决它——首先是自己想(“你”),然后是小组讨论(“你们”),最后是全班一起来(“我们”)。

The result was a process that replaced answer-getting with what Lampert called sense-making. By pushing students to talk about math, she invited them to share the misunderstandings most American students keep quiet until the test. In the process, she gave them an opportunity to realize, on their own, why their answers were wrong.

通过由此形成的一套程序,兰珀特所说的“理解”就取代了“解题”。通过调动学生们讨论数学,她也引导他们交流彼此的错解,而多数美国人是直到考试都还对此一声不吭的。这一过程让学生们有机会自己认识到自己的答案为什么是错的。

Lampert, who until recently was a professor of education at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, now works for the Boston Teacher Residency, a program serving Boston public schools, and the New Visions for Public Schools network in New York City, instructing educators on how to train teachers.

兰珀特不久前还是密歇根大学安娜堡分校的教育学教授,现任职于“波士顿教师驻校”项目,该项目专为波士顿公立学校服务,同时她还在纽约市的公立学校新视野网络任职,职责是对教育者训练教师的方法进行指导。

In her book, “Teaching Problems and the Problems of Teaching,” Lampert tells the story of how one of her fifth-grade classes learned fractions. One day, a student made a “conjecture” that reflected a common misconception among children. The fraction 5 / 6, the student argued, goes on the same place on the number line as 5 / 12.

在她的著作《问题的教学与教学的问题》中,兰珀特讲述了她的一个五年级班级如何学习分数的故事。某天,有学生提出了一个“猜想”,他认为分数5/6和5/12在数轴上应该处于同一位置。这是孩子们中间很常见的一个误解。

For the rest of the class period, the student listened as a lineup of peers detailed all the reasons the two numbers couldn’t possibly be equivalent, even though they had the same numerator. A few days later, when Lampert gave a quiz on the topic (“Prove that 3 / 12 = 1 / 4 ,” for example), the student could confidently declare why: “Three sections of the 12 go into each fourth.”

这节课之后的时间里,这个学生就听他的一组同伴依次详细说明为什么这两个数不可能相等,尽管它们分子相同。几天之后,兰珀特针对这个内容出了个小测验(比如,“证明3/12=1/4”),学生们能够很有信心地说明理由:“12份中的三份,相当于四份中的一份”。

Over the years, observers who have studied Lampert’s classroom have found that students learn an unusual amount of math. Rather than forgetting algorithms, they retain and even understand them. One boy who began fifth grade declaring math to be his worst subject ended it able to solve multiplication, long division and fraction problems, not to mention simple multivariable equations. It’s hard to look at Lampert’s results without concluding that with the help of a great teacher, even Americans can become the so-called math people we don’t think we are.

多年以来,通过研究兰珀特的课堂,观察者已经发现,学生们学到的数学多到超乎寻常。他们不会忘记运算法则,不但记住了,而且还能理解。有个男生刚进五年级时说数学是他最差的科目,但五年级结束时他却学会了解决乘法、长除和分数问题,更别说简单的多元方程组了。看到兰珀特的成绩,人们自会得出这样的结论:只要有了不起的教师,即使美国人也可能变成数学民族,我们现在可不会这么认为。

Among math reformers, Lampert’s work gained attention. Her research was cited in the same N.C.T.M. standards documents that Takahashi later pored over. She was featured in Time magazine in 1989 and was retained by the producers of “Sesame Street” to help create the show “Square One Television,” aimed at making math accessible to children.

兰珀特的工作在数学改革家中受到了关注。高桥昭彦曾仔细研读过的NCTM教学标准文件就曾引用过她的研究。1989年,《时代周刊》曾刊载关于她的特稿。她还曾被《芝麻街》(Sesame Street)的制片人所聘,协助创作了“起点电视”节目,旨在让数学更易于被小孩子理解。

Yet as her ideas took off, she began to see a problem. In Japan, she was influencing teachers she had never met, by way of the N.C.T.M. standards. But where she lived, in America, teachers had few opportunities for learning the methods she developed.

然而在她的理念流行起来之后,她开始注意到一个问题。在日本,通过NCTM标准,她正在持续影响着许多她从未谋面的教师。但在她生活的美国,教师们却很少有机会学习她所开发的这些方法。

【照片插图来自于Andrew B. Myers 道具师:Randi Brookman Harris。蝴蝶图标来自于Tim Boelaars】

American institutions charged with training teachers in new approaches to math have proved largely unable to do it. At most education schools, the professors with the research budgets and deanships have little interest in the science of teaching. Indeed, when Lampert attended Harvard’s Graduate School of Education in the 1970s, she could find only one listing in the entire course catalog that used the word “teaching” in its title. (Today only 19 out of 231 courses include it.) Methods courses, meanwhile, are usually taught by the lowest ranks of professors — chronically underpaid, overworked and, ultimately, ineffective.

对教师们负有新方法培训之责的美国机构,已被证明几乎无力承担这一任务。在多数教育学校里,拥有研究预算和系主任职位的教授们很少有兴趣钻研教育科学。事实上,兰珀特1970年代在哈佛大学的教育学研究所上学时,在整个课程目录表中,名称里带有“教学”一词的课程竟然只有一门。(今天的231门课中也只有19门含有该词。)同时,方法课通常都由级别最低的教授来上——常年低薪、工作负担过重,而且终究并不称职。

Without the right training, most teachers do not understand math well enough to teach it the way Lampert does. “Remember,” Lampert says, “American teachers are only a subset of Americans.” As graduates of American schools, they are no more likely to display numeracy than the rest of us. “I’m just not a math person,” Lampert says her education students would say with an apologetic shrug.

由于缺乏正确的培训,多数教师对数学的了解不够深入,不能像兰珀特那样教书。兰珀特说:“记住,美国教师只是美国人的一个子集”。他们毕业于美国的学校,数学程度并不比其余美国人更高。兰珀特说,她的教育学学生会抱歉地耸耸肩跟她说“我确实不擅长数学”。

Consequently, the most powerful influence on teachers is the one most beyond our control. The sociologist Dan Lortie calls the phenomenon the apprenticeship of observation. Teachers learn to teach primarily by recalling their memories of having been taught, an average of 13,000 hours of instruction over a typical childhood. The apprenticeship of observation exacerbates what the education scholar Suzanne Wilson calls education reform’s double bind. The very people who embody the problem — teachers — are also the ones charged with solving it.

结果是,对教师们最有影响的因素,就是最不由我们掌控的。社会学家丹·洛尔蒂将这种现象叫做“旁观习艺”(apprenticeship of observation)。教师们主要是通过回忆自己的受教经历来学习教书,一般人童年时接受的教导平均有13000小时。“旁观习艺”现象加剧了教育学家苏珊·威尔逊所称的教育改革双重困境:问题本就在于教师,而负责解决这一问题的也是教师。

Lampert witnessed the effects of the double bind in 1986, a year after California announced its intention to adopt “teaching for understanding,” a style of math instruction similar to Lampert’s. A team of researchers that included Lampert’s husband, David Cohen, traveled to California to see how the teachers were doing as they began to put the reforms into practice.

1986年,也就是加利福尼亚宣布要采用与兰珀特的数学教育方式类似的“达成理解的教学”的第二年,兰珀特见证了这种双重困境的后果。教师们开始将改革付诸实践后,一个研究小组(其中包括兰珀特的丈夫大卫·科恩)就跑到加利福尼亚去观察他们到底是如何做的。

But after studying three dozen classrooms over four years, they found the new teaching simply wasn’t happening. Some of the failure could be explained by active resistance. One teacher deliberately replaced a new textbook’s problem-solving pages with the old worksheets he was accustomed to using.

4年以后,通过研究30多个课堂,他们发现“新教学法”根本没有出现。这种失败部分源于主动的抵制。有个教师就故意拿他惯于使用的旧习题集替换掉了新教材中的问题解答部分。

Much more common, though, were teachers who wanted to change, and were willing to work hard to do it, but didn’t know how. Cohen observed one teacher, for example, who claimed to have incited a “revolution” in her classroom. But on closer inspection, her classroom had changed but not in the way California reformers intended it to.

然而,更为普遍的情况是,教师们想要有所改变,也愿意努力去实现改变,但他们不知道如何下手。科恩就观察了一位自称在课堂里引发了“革命”的教师。细查发现,她的课堂确实有所改变,但方向却与加利福尼亚改革家的意图不同。

Instead of focusing on mathematical ideas, she inserted new activities into the traditional “I, We You” framework. The supposedly cooperative learning groups she used to replace her rows of desks, for example, seemed in practice less a tool to encourage discussion than a means to dismiss the class for lunch (this group can line up first, now that group, etc.).

她没能聚焦于数学理念,而是在传统的“我、我们、你”框架中加入了一些新活动。比如,她撤掉成排的课桌,代之以意在增进合作的学习小组,但从实践情形来看,这一替换与其说是鼓励了讨论,倒不如说是方便了学生下课吃午饭(比如,这组先排队,那组再上)。

And how could she have known to do anything different? Her principal praised her efforts, holding them up as an example for others. Official math-reform training did not help, either. Sometimes trainers offered patently bad information — failing to clarify, for example, that even though teachers were to elicit wrong answers from students, they still needed, eventually, to get to correct ones. Textbooks, too, barely changed, despite publishers’ claims to the contrary.

不过,她又能知晓什么其它办法呢?校长鼓励了她所做的努力,将其树为他人学习的榜样。官方的数学改革培训也没能帮到她。有时候培训者还会提供明显糟糕的信息——比如,没能清楚地说明,尽管教师们需要从学生那里诱导出错误的回答,但最终仍然需要让学生们给出正确的答案。同样,教材也基本保持原样,尽管出版社声称已经做出了改变。

With the Common Core, teachers are once more being asked to unlearn an old approach and learn an entirely new one, essentially on their own. Training is still weak and infrequent, and principals — who are no more skilled at math than their teachers — remain unprepared to offer support.

现在公共核心来了,再一次要求教师们忘记旧的方法,而且基本上要全靠他们自己去学会全新的方法。培训力度仍很弱,且频率很低,校长们——其数学技能当然跟教师们一样差——也仍然是毫无准备,无力提供支持。

Textbooks, once again, have received only surface adjustments, despite the shiny Common Core labels that decorate their covers. “To have a vendor say their product is Common Core is close to meaningless,” says Phil Daro, an author of the math standards.

教材依然如故只做了表面的调整,就只有封面上装饰有公共核心那闪闪发亮的标签。该数学标准的作者之一菲尔·达罗说:“让小贩们去说他们的产品是公共核心,这几近于毫无意义。”

Left to their own devices, teachers are once again trying to incorporate new ideas into old scripts, often botching them in the process. One especially nonsensical result stems from the Common Core’s suggestion that students not just find answers but also “illustrate and explain the calculation by using equations, rectangular arrays, and/or area models.”

教师们只能自摸门道,又一次尝试把新理念塞进旧的脚本里,通常还只能一边尝试一边缝缝补补。公共核心建议学生们不仅要找到答案,而且要“运用等式、矩形阵列和(或)面积模型来图解和阐述其计算过程”,这一建议导致了一个特别荒谬的结果。

The idea of utilizing arrays of dots makes sense in the hands of a skilled teacher, who can use them to help a student understand how multiplication actually works. For example, a teacher trying to explain multiplication might ask a student to first draw three rows of dots with two dots in each row and then imagine what the picture would look like with three or four or five dots in each row.

在经验丰富的教师手中,使用成列的小圆点这一想法确实有道理,有助于学生理解乘法的实际运算过程。比如,正在讲解乘法的教师可以让学生先画3排小圆点,每排2个,然后让他去想象如果每排有3个或4个或5个点,会构成什么样的图形。

Guiding the student through the exercise, the teacher could help her see that each march up the times table (3x2, 3x3, 3x4) just means adding another dot per row. But if a teacher doesn’t use the dots to illustrate bigger ideas, they become just another meaningless exercise.

通过引导学生做这种活动,教师可以让他们看到,乘法表上每进一格(3x2,3x3,3x4),意思不过是每排多加1个圆点而已。但是如果教师使用这些圆点不是为了说明更大的概念,它们就只会成为另一种无意义的演练。

Instead of memorizing familiar steps, students now practice even stranger rituals, like drawing dots only to count them or breaking simple addition problems into complicated forms (62+26, for example, must become 60+2+20+6) without understanding why. This can make for even poorer math students. “In the hands of unprepared teachers,” Lampert says, “alternative algorithms are worse than just teaching them standard algorithms.”

学生们不用再背诵熟悉的步骤,但现在却要练习更为奇怪的程序,比如画小圆点就是为了数点数,或将简单的加法问题拆解为复杂形式(如62+26必须变成60+2+20+6),而并不理解这么做的理由。这可能使学生的数学技能变得更差。兰珀特说:“在毫无准备的教师手中,换个算法教学生比只按常规算法来教效果更糟。”

No wonder parents and some mathematicians denigrate the reforms as “fuzzy math.” In the warped way untrained teachers interpret them, they are fuzzy.

家长们和一些数学家将这一改革贬称为“糊涂数学”,这一点都不奇怪。由未经训练的教师们扭曲表达之后,这一改革确实是糊涂的。

When Akihiko Takahashi arrived in America, he was surprised to find how rarely teachers discussed their teaching methods. A year after he got to Chicago, he went to a one-day conference of teachers and mathematicians and was perplexed by the fact that the gathering occurred only twice a year.

高桥昭彦到了美国后,吃惊地发现极少有教师会讨论各自的教学方法。到芝加哥后一年,他去参加一个由教师和数学家组成的会议,会期一天。他对该集会每年只办两次这一事实感到困惑。

In Japan, meetings between math-education professors and teachers happened as a matter of course, even before the new American ideas arrived. More distressing to Takahashi was that American teachers had almost no opportunities to watch one another teach.

在日本,即使是在美国人的新理念传入之前,数学教育教授和教师之间的会议也是一件理所当然的事。更令高桥昭彦感到忧虑的是,美国教师几乎没有任何观摩彼此教学的机会。

In Japan, teachers had always depended on jugyokenkyu, which translates literally as “lesson study,” a set of practices that Japanese teachers use to hone their craft. A teacher first plans lessons, then teaches in front of an audience of students and other teachers along with at least one university observer. Then the observers talk with the teacher about what has just taken place. Each public lesson poses a hypothesis, a new idea about how to help children learn. And each discussion offers a chance to determine whether it worked.

日本教师历来依赖“授业研究”(jugyokenkyu),这是他们用以磨炼自身技艺的一套做法。教师首先备课,然后要在由学生、其他教师和至少一名来自大学的旁听者组成的听众面前讲授。然后旁听者要和该教师交流刚才的授课如何。每一次公开课都会提出一条假想,即如何帮助孩子们学习的新想法。而每一次讨论都为确定这一想法是否有效提供了机会。

Without jugyokenkyu, it was no wonder the American teachers’ work fell short of the model set by their best thinkers. Without jugyokenyku, Takahashi never would have learned to teach at all. Neither, certainly, would the rest of Japan’s teachers.

因此毫不奇怪,由于没有授业研究,美国教师的工作达不到由美国最好的思想家所设定的典范。如果没有授业研究,高桥昭彦压根就无从学会如何教书。当然,日本的其他教师也同样学不会。

The best discussions were the most microscopic, minute-by-minute recollections of what had occurred, with commentary. If the students were struggling to represent their subtractions visually, why not help them by, say, arranging tile blocks in groups of 10, a teacher would suggest.

其中最好的讨论就是对授课过程最微观的、一分钟一分钟的回忆和评论。某位教师可能建议,如果学生们难以用形象的方式来表达减法,为什么不帮帮他们呢,比如让他们10个一组地排列一些砖块。

Or after a geometry lesson, someone might note the inherent challenge for children in seeing angles as not just corners of a triangle but as quantities — a more difficult stretch than making the same mental step for area. By the end, the teachers had learned not just how to teach the material from that day but also about math and the shape of students’ thoughts and how to mold them.

或者一堂几何课之后,也许有人会注意到,对于小孩子而言,把角不仅视作三角形的角落,而且视为一种数量,这件事有着其固有的挑战——这种延伸比在面积问题上完成同样的思考步骤更为困难。最后,教师们不仅能学到如何讲授当日要讲的内容,也能学到数学和学生思维的特性,以及如何塑造他们的思维方法。

If teachers weren’t able to observe the methods firsthand, they could find textbooks, written by the leading instructors and focusing on the idea of allowing students to work on a single problem each day. Lesson study helped the textbook writers home in on the most productive problems. For example, if you are trying to decide on the best problem to teach children to subtract a one-digit number from a two-digit number using borrowing, or regrouping, you have many choices: 11 minus 2, 18 minus 9, etc.

如果教师们无法亲自观摩这种方法,他们还可以找教材。教材由首屈一指的教育者写成,专注于让学生每天攻克一个题目这一理念。教学研究能让教材作者专门注意那些最有成效的题目。比如,你要教小孩子用借数法或重组法来做两位数减一位数的减法,假如你想知道用哪个题目最好,就可能面临多种选择:比如11减2,18减9等。

Yet from all these options, five of the six textbook companies in Japan converged on the same exact problem, ToshiakiraFujii, a professor of math education at Tokyo Gakugei University, told me. They determined that 13 minus 9 was the best.

然而,东京学艺大学(Tokyo Gakugei University)的藤井斋亮教授告诉我,在那么多的选择中,日本六分之五的教材出版社扎堆似地选择了完全一样的一个题目。他们都确认13减9是最好的题目。

Other problems, it turned out, were likely to lead students to discover only one solution method. With 12 minus 3, for instance, the natural approach for most students was to take away 2 and then 1 (the subtraction-subtraction method). Very few would take 3 from 10 and then add back 2 (the subtraction-addition method).

实践表明,其它题目都很可能只能引导学生发现一种解法。就拿12减3来说,大部分学生很自然地就会先减去2再减去1(先减再减法)。很少有人会先从10中减去3,再加回2(先减再加法)。

But Japanese teachers knew that students were best served by understanding both methods. They used 13 minus 9 because, faced with that particular problem, students were equally likely to employ subtraction-subtraction (take away 3 to get 10, and then subtract the remaining 6 to get 4) as they were to use subtraction-addition (break 13 into 10 and 3, and then take 9 from 10 and add the remaining 1 and 3 to get 4). A teacher leading the “We” part of the lesson, when students shared their strategies, could do so with full confidence that both methods would emerge.

但是日本的教师知道,同时领会这两种方法,对学生最好。他们使用13减9这个题目,是因为学生们在面对这一特殊题目时,使用先减再减法(减3得10,再减剩下的6得4)和先减再加法(把13拆为10加3,从10中减去9,把剩下的1和3相加得4)的可能性一样大。课堂上,当教师引导学生做“我们”这一步(让学生们交流彼此的解题方法)时,就有信心看到两种方法都会出现。

By 1995, when American researchers videotaped eighth-grade classrooms in the United States and Japan, Japanese schools had overwhelmingly traded the old “I, We, You” script for “You, Y’all, We.” (American schools, meanwhile didn’t look much different than they did before the reforms.)

到1995年,当美国研究者对美日两国的八年级数学课堂进行录像时,日本学校已经势不可挡地用“你、你们、我们”模式取代了老式的“我、我们、你”脚本。(与此同时,美国学校则看起来与改革前相比没有什么大的变化)。

Japanese students had changed too. Participating in class, they spoke more often than Americans and had more to say. In fact, when Takahashi came to Chicago initially, the first thing he noticed was how uncomfortably silent all the classrooms were. One teacher must have said, “Shh!” a hundred times, he said.

日本学生也有所改变。在课堂参与上,他们比美国人说得更多,也更有东西可说。事实上,高桥昭彦初到芝加哥时,他注意到的第一件事就是所有课堂都安静得令人极为难受。他说,有个老师肯定说了一百次“嘘!”。

Later, when he took American visitors on tours of Japanese schools, he had to warn them about the noise from children talking, arguing, shrieking about the best way to solve problems. The research showed that Japanese students initiated the method for solving a problem in 40 percent of the lessons; Americans initiated 9 percent of the time.

后来,他带美国访客参观日本学校,不得不预先提醒他们,孩子们就最佳解题方法进行交谈、争辩、尖叫时会很吵。前述研究表明,日本学生在40%的课上提出过解答问题的方法,美国学生则为9%。

Similarly, 96 percent of American students’ work fell into the category of “practice,” while Japanese students spent only 41 percent of their time practicing. Almost half of Japanese students’ time was spent doing work that the researchers termed “invent/think.” (American students spent less than 1 percent of their time on it.)

同样,美国学生课堂上所做的,有96%属于“练习”这个类别,而日本学生做练习的时间只有41%。日本学生有将近一半的时间是在做研究者称为“创造/思考”一类的事。(美国学生做此类活动的时间不到1%)。

Even the equipment in classrooms reflected the focus on getting students to think. Whereas American teachers all used overhead projectors, allowing them to focus students’ attention on the teacher’s rules and equations, rather than their own, in Japan, the preferred device was a blackboard, allowing students to track the evolution of everyone’s ideas.

即便是教室里的教具也体现了对于促进学生思考的关注。美国教师习惯用越过头顶的投影仪,方便他们将学生的注意力集中于教师们的、而非学生自己的规则和等式。日本老师更喜爱的教具则是黑板,它能让学生们追踪每个人想法的演变。

Japanese schools are far from perfect. Though lesson study is pervasive in elementary and middle school, it is less so in high school, where the emphasis is on cramming for college entrance exams. As is true in the United States, lower-income students in Japan have recently been falling behind their peers, and people there worry about staying competitive on international tests.

日本学校远非完美。尽管小学和初中里面授业研究很普遍,但在高中就并非如此了。高中侧重的是为大学入学考试死记硬背。跟美国一样,来自收入较低家庭的日本学生近来也已落后于同龄人,同时,日本人也很担心他们在国际测试中的竞争力。

Yet while the United States regularly hovers in the middle of the pack or below on these tests, Japan scores at the top. And other countries now inching ahead of Japan imitate the

jugyokenkyuapproach. Some, like China, do this by drawing on their own native

jugyokenkyu-style traditions

(zuanyanjiaocai, or “studying teaching materials intensively,” Chinese teachers call it).

不过,与美国在这类测试中长期徘徊于中等或下等不同,日本得分总是靠前。而其他正在慢慢超过日本的国家,也模仿了授业研究方法。有些国家,比如中国,还吸收了他们自己本土存在的授业研究式的传统(中国教师把它叫做“钻研教材”)。

Others, including Singapore, adopt lesson study as a deliberate matter of government policy. Finland, meanwhile, made the shift by carving out time for teachers to spend learning. There, as in Japan, teachers teach for 600 or fewer hours each school year, leaving them ample time to prepare, revise and learn. By contrast, American teachers spend nearly 1,100 hours with little feedback.

其他国家,包括新加坡,将教学研究接纳为政府政策的一项明确内容。同时,芬兰的应对办法是为教师提供用于学习的时间。跟日本一样,芬兰教师每学年只要教课600或不到600小时,有充足的时间备课、修订和学习。与此相比,美国教师每学年教课将近1100小时,还得不到多少反馈。

It could be tempting to dismiss Japan’s success as a cultural novelty, an unreproducible result of an affluent, homogeneous, and math-positive society. Perhaps the Japanese are simply the “math people” Americans aren’t. Yet when I visited Japan, every teacher I spoke to told me a story that sounded distinctly American.

有种想法很吸引人,那就是认为日本的成功乃是一种文化上的新奇事物,是富裕、同质且有数学天赋的社会的一个不可复制的结果,然后对之不加理会。也许日本人就是那种“数学民族”,而美国人不是。不过,我在日本旅游时,每位跟我交谈过的教师都跟我讲过一个听起来美国味特别浓的故事。

“I used to hate math,” an elementary-school teacher named Shinichiro Kurita said through a translator. “I couldn’t calculate. I was slow. I was always at the bottom of the ladder, wondering why I had to memorize these equations.” Like Takahashi, when he went to college and saw his instructors teaching differently, “it was an enlightenment.”

一位名为栗田辰一朗的小学教师通过翻译跟我说:“我以前特别讨厌数学。我不会计算,反应也慢。我总是处于梯子的最底下,心想为什么必须要背那些等式。”就跟高桥昭彦一样,他到了大学以后,得以看到他的老师用一种不同的方式上课,“那是一种启蒙”。

Learning to teach the new way himself was not easy. “I had so much trouble,” Kurita said. “I had absolutely no idea how to do it.” He listened carefully for what Japanese teachers call children’s twitters — mumbled nuggets of inchoate thoughts that teachers can mold into the fully formed concept they are trying to teach.

他本人学习这种新的教学方式并不容易。栗田辰一朗说道:“困难重重。我完全不知道怎么去做”。他仔细倾听日本教师所说的“小孩的叽喳”——含有尚未成熟的想法的含糊信息,教师们可以将之形塑成为他们正要讲授的完全成型的概念。

And he worked hard on

bansho, the term Japanese teachers use to describe the art of blackboard writing that helps students visualize the flow of ideas from problem to solution to broader mathematical principles. But for all his efforts, he said, “the children didn’t twitter, and I couldn’t write on the blackboard.” Yet Kurita didn’t give up — and he had resources to help him persevere.

而且他也努力学做板书,板书的作用是帮助学生形象地看到从题目到解答到更广泛的数学原理中的观念流变。然而不管他如何努力,他说:“孩子们不叽喳,我也写不出板书”。不过栗田辰一朗没有放弃,而且他也有资源支撑他继续坚持。

He went to study sessions with other teachers, watched as many public lessons as he could and spent time with his old professors. Eventually, as he learned more, his students started to do the same. Today Kurita is the head of the math department at Setagaya Elementary School in Tokyo, the position once held by Takahashi’s mentor, Matsuyama.

他和其他教师一起去参加研讨会,尽其所能地观看了许多公开课,还与他以前的教授进行交流。最终,随着他所学日多,他的学生也开始如此。如今,栗田辰一朗是东京世田谷小学校数学部的主任,这个职位以前曾由高桥昭彦的导师松山武士充任。

Of all the lessons Japan has to offer the United States, the most important might be the belief in patience and the possibility of change. Japan, after all, was able to shift a country full of teachers to a new approach. Telling me his story, Kurita quoted what he described as an old Japanese saying about perseverance: “Sit on a stone for three years to accomplish anything.”

在日本能够向美国提供的诸多教益中,最重要的也许是对耐心和改变的可能性所抱持的信念。日本最终得以将一个满是教师的国家导向一种新的方法。栗田辰一朗跟我讲述他的故事时,引用了一句日本老话:石坐三年自然暖,就是说要有毅力。

Admittedly, a tenacious commitment to improvement seems to be part of the Japanese national heritage, showing up among teachers, autoworkers, sushi chefs and tea-ceremony masters. Yet for his part, Akihiko Takahashi extends his optimism even to a cause that can sometimes seem hopeless — the United States.

必须承认,对精益求精的执着信奉似乎是日本民族遗产的一部分,突出体现在教师、汽车工人、寿司厨师和茶道大师身上。不过就高桥昭彦而言,他甚至还将这种乐观精神拓展到了一个有时看起来完全无望的事业之上——美国。

After the great disappointment of moving here in 1991, he made a decision his colleagues back in Japan thought was strange. He decided to stay and try to help American teachers embrace the innovative ideas that reformers like Magdalene Lampert pioneered.

在经历了1991年搬到此国时的巨大失望之后,他做出了一个令他的日本同事感到奇怪的决定。他决心留在美国,并试着帮助美国教师采用兰珀特等改革家所开创的创新理念。

Today Takahashi lives in Chicago and holds a full-time job in the education department at DePaul University. (He also has a special appointment at his alma mater in Japan, where he and his wife frequently visit.) When it comes to transforming teaching in America, Takahashi sees promise in individual American schools that have decided to embrace lesson study.

高桥昭彦现居芝加哥,在德保罗大学(DePaul Univerisity)的教育系拥有全职工作。(他还在他的日本母校拥有一个特殊职位,并经常与妻子一起回去)。在美国教学转型问题上,高桥昭彦从那些决心采纳教学研究方法的个别美国学校那里看到了希望。

Some do this deliberately, working with Takahashi to transform the way they teach math. Others have built versions of lesson study without using that name. Sometimes these efforts turn out to be duds. When carefully implemented, though, they show promise. In one experiment in which more than 200 American teachers took part in lesson study, student achievement rose, as did teachers’ math knowledge — two rare accomplishments.

有些学校是刻意如此去做的,它们跟高桥昭彦合作,尝试改变教授数学的方式。其它学校也开展了不同形式的教学研究,只是没有采用这个名称。有时这些努力会归于失败。但如果精心实施,那就颇有前景。某项实验中,有200多名美国教师参与了教学研究,学生成绩有所提高,教师们的数学知识也有所提高——这两项成就都非常稀罕。

Training teachers in a new way of thinking will take time, and American parents will need to be patient. In Japan, the transition did not happen overnight. When Takahashi began teaching in the new style, parents initially complained about the young instructor experimenting on their children.

训练教师们用新的方式思考,这需要时间。所以美国家长也需要耐心。日本的转型不是一夜之间实现的。当初,高桥昭彦开始用新方式教书时,家长们最初也对这位年轻老师在他们的孩子身上做实验表示抱怨。

But his early explorations were confined to just a few lessons, giving him a chance to learn what he was doing and to bring the parents along too. He began sending home a monthly newsletter summarizing what the students had done in class and why.

不过他最初的探索也只局限于不多的一些课程,他由此有机会搞清自己在做什么,同时也能带着家长们一起进步。后来他开始每个月寄一份通讯给家长,概述学生们在课堂上都做了什么及其原因。

By his third year, he was sending out the newsletter every day. If they were going to support their children, and support Takahashi, the parents needed to know the new math as well. And over time, they learned.

到第三年,他寄出的通讯就成了每日一份。要让家长们支持他们的孩子,支持高桥昭彦,他们同样需要了解这种新数学。最后,他们学会了。

To cure our innumeracy, we will have to accept that the traditional approach we take to teaching math — the one that can be mind-numbing, but also comfortingly familiar — does not work. We will have to come to see math not as a list of rules to be memorized but as a way of looking at the world that really makes sense.

要治疗我们的数盲,就必须承认,我们用以教授数学的传统方法——那种可能会麻木心灵,不过同时又让我们感到熟悉而安逸的方法——行不通。我们终究必须要认识到,数学不是一份有待背诵的规则列表,而是一种有意义的看待世界的方式。

The other shift Americans will have to make extends beyond just math. Across all school subjects, teachers receive a pale imitation of the preparation, support and tools they need. And across all subjects, the neglect shows in students’ work. In addition to misunderstanding math, American students also, on average, write weakly, read poorly, think unscientifically and grasp history only superficially.

美国人必须要做的另一个转变超出了数学的范围。学校里所有科目的老师,在他们所需要的准备、支持和工具方面,都只能得到劣质的仿品。这种轻忽在学生所有学科的成绩中都表现了出来。除了搞不懂数学之外,平均而言,美国学生写作也差,阅读也差,不能进行科学思考,对历史也只有肤浅的了解。

Examining nearly 3,000 teachers in six school districts, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation recently found that nearly two-thirds scored less than “proficient” in the areas of “intellectual challenge” and “classroom discourse.” Odds-defying individual teachers can be found in every state, but the overall picture is of a profession struggling to make the best of an impossible hand.

盖茨基金会最近针对6个学区近3000名教师的测验发现,有将近三分之二的教师在“智识挑战”和“课堂讨论”领域达不到“熟练”级别。背离这一几率的个别教师在每个州都能找到,不过整体的图景就是这样:这个行业中的人正在艰苦努力,试图把手里的一副烂牌打好。

Most policies aimed at improving teaching conceive of the job not as a craft that needs to be taught but as a natural-born talent that teachers either decide to muster or don’t possess. Instead of acknowledging that changes like the new math are something teachers must learn over time, we mandate them as “standards” that teachers are expected to simply “adopt.” We shouldn’t be surprised, then, that their students don’t improve.

意在改进教学的多数政策,都没有将教学视作一种需要学习的技艺,而是把它视做一种与生俱来的天赋,教师们要么只需要召唤技能,要么就干脆没有。我们没有认识到像“新数学”这种转变,教师们是必须花时间去学的。相反,我们把新数学颁布为“标准”,教师们只要直接“采用”就好。这样,他们的学生没有进步,我们就不应该对此感到惊讶。

Here, too, the Japanese experience is telling. The teachers I met in Tokyo had changed not just their ideas about math; they also changed their whole conception of what it means to be a teacher.

在这里,日本人的经验同样有益。我在东京见过的教师不但已经转变了他们对数学的观念,他们还转变了他们对身为教师意味着什么的整个理解。

“The term ‘teaching’ came to mean something totally different to me,” a teacher named Hideto Hirayama told me through a translator. It was more sophisticated, more challenging — and more rewarding.

一位名叫平山秀人的教师通过翻译告诉我:“对我来说,‘教书’这个词的意义已经完全不同”。它变得更为精致复杂,更富于挑战——回报也更大。

“The moment that a child changes, the moment that he understands something, is amazing, and this transition happens right before your eyes,” he said. “It seems like my heart stops every day.”

“一个孩子发生变化的时候,他理解了某个事物的时候,那真是美妙,这种转变就正好发生在你眼前”,他说,“就好像我每天都会心跳停止一样。”

(编辑:辉格@whigzhou)

*注:本译文未经原作者授权,本站对原文不持有也不主张任何权利,如果你恰好对原文拥有权益并希望我们移除相关内容,请私信联系,我们会立即作出响应。

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

订阅

订阅