【2017-02-26】

@whigzhou: 越想越觉得border-adjustment是个好东西,最好的地方是它可能会把川普糊弄过去(或者帮川普把他的支持者糊弄过去?),以他(和他的支持者)对经济问题的理解能力,这很可能。

@史搞特:这个border adjustment tax跟关税有啥不同

@whigzhou: 差别是:关税是对跨境交易额外征了一笔税,因而会提高税负,降低贸易额,而BA只是改变了跨境交易的税负分布(more...)

【2017-02-26】

@whigzhou: 越想越觉得border-adjustment是个好东西,最好的地方是它可能会把川普糊弄过去(或者帮川普把他的支持者糊弄过去?),以他(和他的支持者)对经济问题的理解能力,这很可能。

@史搞特:这个border adjustment tax跟关税有啥不同

@whigzhou: 差别是:关税是对跨境交易额外征了一笔税,因而会提高税负,降低贸易额,而BA只是改变了跨境交易的税负分布(more...)

【2017-02-23】

@研二公知苗 不少人在讲移民问题时,都忽略社会,文化和政治成本,只讲纯经济收益。讲经济收益时,理论上,无论是受高等教育的合法移民还是从事低端工作的非法移民带来的纯经济收益理论上都是正的。但是这种收益不是一些人描绘的帕累托改进。相反,这种收益实际上带有很强的再分配性质。尤其是考虑到非法移民增加了低端工作岗位的供给,压低了低端岗位的工资,实际上是一种带有劫贫济富性质的再分配。

@whigzhou: 你说的是分配效应,distributive effec(more...)

【2017-02-21】

@whigzhou: 如果让你列出五件东西,没了它们美国(在你眼里)就不再是美国了,你会选哪五件?我的选择:持枪权,stand your ground,陪审团,最高法院,州权。

@都市学派:宪法必须排第一。

@whigzhou: 宪法很难判定怎么算『没了』,我列的五件都很容易判别

@慕容飞宇gg:辉总的意思是没了其中一件还是全部没了?

@whigzhou: 每少一件就更远离一点啊(幸亏我不是本质主义者)

(more...)【2017-02-17】

罗伯斯庇尔24岁时当上了阿拉斯主教区刑事法庭的法官,因为这项工作和他强烈反对死刑的原则相冲突,不久便辞职——哈哈,这是我今天听到的最大笑话。

前几天还听到个笑话,有位自由派议员受不了Betsy DeVos当上教育部长,说要让自家孩子home schooling,也很劲爆。

Is the FDA Too Conservative or Too Aggressive?

FDA,过于保守还是过于激进?

作者:Alex Tabarrok @ 2015-08-26

译者:小聂(@PuppetMaster)

校对:babyface_claire (@许你疯不许你傻)

来源:Marginal Revolution,http://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2015/08/is-the-fda-too-conservative-or-too-aggressive.html

I have long argued that the FDA has an incentive to delay the introduction of new drugs because approving a bad drug (Type I error) has more severe consequences for the FDA than does failing to approve a good drug (Type II error). In the former case at least some victims are identifiable and the New York Times writes stories about them and how they died because the FDA failed. In the latter case, when the FDA fails to approve a good drug, people die but the bodies are buried in an invisible graveyard.

我一直认为,FDA有充分的动机来延迟新药审批,因为对于FDA来说,批准一种不合格的药(第一型错误)比拒绝一种合格的药(第二型错误)后果要严重(more...)

“…we show that the current standards of drug-approval are weighted more on avoiding a Type I error (approving ineffective therapies) rather than a Type II error (rejecting effective therapies). For example, the standard Type I error of 2.5% is too conservative for clinical trials of therapies for pancreatic cancer—a disease with a 5-year survival rate of 1% for stage IV patients (American Cancer Society estimate, last updated 3 February 2013). The BDA-optimal size for these clinical trials is 27.9%, reflecting the fact that, for these desperate patients, the cost of trying an ineffective drug is considerably less than the cost of not trying an effective one.” “……我们的结果显示,现有的药品审批标准更偏向于避免第一型错误(批准无效的疗法)而不是避免第二型错误(拒绝有效的疗法)。譬如,对于胰腺癌——一种四期病人五年内存活率仅有1%的疾病(美国癌症协会预测,最后更新于2013年2月3日)——标准的2.5%第一型错误率实在是太过保守。这些临床试验经过贝叶斯决策分析优化过的容错标准为27.9%,这表明对于这些绝望的患者们,试用一种无效药物的成本大大低于不尝试一种有效药物的成本。”(The authors also find that the FDA is occasionally a little too aggressive but these errors are much smaller, for example, the authors find that for prostate cancer therapies the optimal significance level is 1.2% compared to a standard rule of 2.5%.) (作者还发现FDA偶尔也会过于激进,但是偏离的程度小得多。例如,前列腺癌治疗的最优显著率是1.2%,而不是标准的2.5%。) The result is important especially because in a number of respects, Montazerhodjat and Lo underestimate the costs of FDA conservatism. Most importantly, the authors are optimizing at the clinical trial stage assuming that the supply of drugs available to be tested is fixed. Larger trials, however, are more expensive and the greater the expense of FDA trials the fewer new drugs will be developed. Thus, a conservative FDA reduces the flow of new drugs to be tested. 该结果十分重要,尤其因为在很多方面,Montazerhodjat和Lo低估了FDA坚持保守标准的成本。最关键的一点在于,作者们假定了待评估药物的供给是恒定的,并在此基础之上来优化临床试验阶段的容错标准。然而大型临床试验往往花费更高,这又导致新药研发的萎缩。因此,保守的FDA会降低新药研发的数量。 In a sense, failing to approve a good drug has two costs, the opportunity cost of lives that could have been saved and the cost of reducing the incentive to invest in R&D. In contrast, approving a bad drug while still an error at least has the advantage of helping to incentivize R&D (similarly, a subsidy to R&D incentivizes R&D in a sense mostly by covering the costs of failed ventures). 从某种意义上说,错误的拒绝一种好的药品有两种成本,一是没能拯救那些本来可以被拯救的病人的机会成本,二是减少了对新药研发做投资的激励所带来的成本。与之相对的是,批准一种不合格的药品,尽管仍旧是个错误,但是至少可以给新药研发带来正面的激励(类似的,对研发进行补贴的一个主要形式就是支付那些失败的研发项目经费,以此来激励更多的新药研发)。 The Montazerhodjat and Lo framework is also static, there is one test and then the story ends. In reality, drug approval has an interesting asymmetric dynamic. When a drug is approved for sale, testing doesn’t stop but moves into another stage, a combination of observational testing and sometimes more RCTs–this, after all, is how adverse events are discovered. Thus, Type I errors are corrected. On the other hand, for a drug that isn’t approved the story does end. With rare exceptions, Type II errors are never corrected. 而且,Montazerhodjat和Lo的分析框架是静态的,一个试验完了,故事就结束了。可实际上,药物审批流程有个独特的非对称机制。当药物被批准上市之后,测试并非就此结束,而是进入下一个阶段,往往由一系列观测性的测试,有时甚至是随机临床试验构成——毕竟,这是发现不良反应的方式。因此,第一型错误往往得到纠正。另一方面,对于一种不被批准的药物,故事到这里就结束了。第二型错误几乎没有被纠正过。 The Montazerhodjat and Lo framework could be interpreted as the reduced form of this dynamic process but it’s better to think about the dynamism explicitly because it suggests that approval can come in a range–for example, approval with a black label warning, approval with evidence grading and so forth. As these procedures tend to reduce the costs of Type I error they tend to increase the costs of FDA conservatism. Montazerhodjat和Lo的框架可以被视为这个机制的一个简化版本,但最好还是能具体的思考一下这个机制,因为这暗示了对于新药的审批结果其实可以是一个范围——比如说,批准(但是带有一个黑色警示标签),或是带有证据强度分级的批准,等等。因为这些举措可以有效降低第一型错误的成本,它们倾向于使FDA在过于保守时受到惩罚。 Montazerhodjat and Lo also don’t examine the implications of heterogeneity of preferences or of disease morbidity and mortality. Some people, for example, are severely disabled by diseases that on average aren’t very severe–the optimal tradeoff for these patients will be different than for the average patient. One size doesn’t fit all. In the standard framework it’s tough luck for these patients. Montazerhodjat 和Lo也并没有检验新药特征的不均一性所带来的影响,这些不均一性主要体现于病人对于治疗结果的偏好或是疾病的发病率和死亡率。例如,有些病人被那些平均而言并不太严重的疾病弄成了严重残疾,对这些病人来说,最优的取舍显然不同于一般的病人。同一个标准并不适用于所有的情况。所以在标准的优化框架里面,这些病人就被忽略了。 But if the non-FDA reviewing apparatus (patients/physicians/hospitals/HMOs/USP/Consumer Reports and so forth) works relatively well, and this is debatable but my work on off-label prescribing suggests that it does, this weighs heavily in favor of relatively large samples but low thresholds for approval. What the FDA is really providing is information and we don’t need product bans to convey information. Thus, heterogeneity plus a reasonable effective post-testing choice process, mediates in favor of a Consumer Reports model for the FDA. 而如果非FDA的评价机构(包括病人、医生、医院、卫生保健组织、美国药典、消费者报告,等等)相对来说起作用的话——这个观点虽然有待商榷,但我给病人开非处方药的经验表明它们是起作用的——这些评价机构就更适合于那些需要大量病人但是批准门槛较低的药。FDA真正提供的是信息,而我们没法从一刀切的禁令中获取有效信息。因此,不均一性,加上一个合理有效的试验后选择机制,间接的指向一个更好的消费者报告式的FDA模式。 The bottom line, however, is that even without taking into account these further points, Montazerhodjat and Lo find that the FDA is far too conservative especially for severe diseases. FDA regulations may appear to be creating safe and effective drugs but they are also creating a deadly caution. 就算不考虑以上这些引申观点,最起码,Montazerhodjat 和 Lo的研究表明,FDA在新药的审批上,尤其是针对特别严重的疾病时,显得过于保守了。FDA的监管或许给我们带来了安全和有效的药品,但是同时也带来了致命的谨慎。 (编辑:辉格@whigzhou) *注:本译文未经原作者授权,本站对原文不持有也不主张任何权利,如果你恰好对原文拥有权益并希望我们移除相关内容,请私信联系,我们会立即作出响应。

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

Class, Caste, and Genes

阶级、种姓和基因

作者:Henry Harpending @ 2012-01-13

译者:尼克基得慢(@尼克基得慢)

校对:辉格(@whigzhou)

来源:West Hunter,https://westhunt.wordpress.com/2012/01/13/class-caste-and-genes/

An article by Sabrina Tavernise appeared in the New York Times a few days ago describing increasing perceptions of class conflict in America, and there is a lot of recent commentary in the press about this report from the Pew Charitable Trust that claims there is less class mobility here than in several other northern countries. It is not very clear to me what the complaints really are or what alternatives exist. If there is any substantial heritability of merit, where merit is whatever leads to class mobility, then mobility ought to turn classes into hereditary castes surprisingly rapidly.

几天前,Sabrina Tavernise一篇描写美国阶级矛盾越发明显的文章刊登在了《纽约时报》上,这份来自皮尤慈善信托基金(the Pew Charitable Trust)的报告宣称美国的阶级流动性少于其他几个北方国家,最近的新闻对此有很多评论。但是我并没有搞清楚他们究竟在抱怨什么或者存在什么可行的替代选项。假设存在实质性的个体优势遗传,同时个体优势总会导致阶级流动,那流动性应该会迅速地把阶层转化为世袭的种姓式分化。

A start at looking int(more...)

This figure shows an initial population with normally distributed merit. A new merit based class system is imposed such that the two new classes are of equal size. In this free meritocracy everyone with merit exceeding the population mean moves into the upper class and everyone with merit less than the average moves into the lower class. The second panel of the figure shows the resulting merit distributions by class before reproduction and the bottom panel shows the distributions after endogamous reproduction. This model assumes that the reshuffling of genes during reproduction leads to normal distributions in the next generation within classes.

上图的顶层显示了个体优势呈正态分布的初始人口。一种基于阶级系统的新优势被引入进来,据此划分的两个新阶级的人口数量相当。在这种自由精英制度中,每个能力超过人口平均值的人都进入上层阶级,每个能力达不到平均值的人都进入下层阶级。上图的中层表示在生育前所处阶级导致的个体优势分布,底层则表示在同阶级通婚生育后的个体优势分布。这个模型假设生育过程中的基因重组会导致同阶级的下一代在个体优势上的正态分布。

The process continues for several generations. By analogy with IQ the additive heritability of merit is set to 0.6 so there are substantial random environmental effects. The second figure shows the evolution of class differences over four generations or about 100 years in human terms.

这个过程持续了几代的时间。通过类比IQ,个体优势的可加性遗传率设为0.6,所以这就有了大量随机的环境影响。下图展示了四代(人类角度的大约100年)时间内阶级差异的演化。

This figure shows an initial population with normally distributed merit. A new merit based class system is imposed such that the two new classes are of equal size. In this free meritocracy everyone with merit exceeding the population mean moves into the upper class and everyone with merit less than the average moves into the lower class. The second panel of the figure shows the resulting merit distributions by class before reproduction and the bottom panel shows the distributions after endogamous reproduction. This model assumes that the reshuffling of genes during reproduction leads to normal distributions in the next generation within classes.

上图的顶层显示了个体优势呈正态分布的初始人口。一种基于阶级系统的新优势被引入进来,据此划分的两个新阶级的人口数量相当。在这种自由精英制度中,每个能力超过人口平均值的人都进入上层阶级,每个能力达不到平均值的人都进入下层阶级。上图的中层表示在生育前所处阶级导致的个体优势分布,底层则表示在同阶级通婚生育后的个体优势分布。这个模型假设生育过程中的基因重组会导致同阶级的下一代在个体优势上的正态分布。

The process continues for several generations. By analogy with IQ the additive heritability of merit is set to 0.6 so there are substantial random environmental effects. The second figure shows the evolution of class differences over four generations or about 100 years in human terms.

这个过程持续了几代的时间。通过类比IQ,个体优势的可加性遗传率设为0.6,所以这就有了大量随机的环境影响。下图展示了四代(人类角度的大约100年)时间内阶级差异的演化。

Class mobility after the first generation is 30% while after four generations it has declined to 10% and continues to decline after that. The average merit in the two classes is about -1SD in the lower and +1SD in the upper on the original scale, corresponding to IQs of 85 and 115.

第一代之后的阶级流动性是30%,而四代之后这个数字就已跌至10%并且之后继续下降。相较于原始水平,较低阶级的平均个体优势降低了一个标准差,较高阶级的平均个体优势增加了一个标准差, 对应的IQ数值为较低阶级的85和较高阶级的115。

Recall that there are no fitness differences in this model. Still, after four generations, about 70% of the variance is between classes, which can be compared to about 35% of the variance among continental human groups for random genetic markers, i.e. colloquially class differences are twice neutral race differences. (The familiar among-population figure of 15% made famous by Lewontin refers to gene differences while here we are comparing genotype differences of diploids, hence the difference between 15 and 35.)

回想下这模型中是没有健康水平的差异的。但在四代之后,阶级之间的方差仍到达了70%,这都可以与随机遗传标记的跨大陆种群间35%的方差相比了,例如,通俗语境中的阶级差异是纯粹种族差异的两倍。(Lewontin提出的著名的种群间15%的差异数据是指基因差异,而这里我们是比较二倍体的基因型差异,因此差别在15到35之间。)

A surprise to me from this model was the rapidity with which classes turn into castes: most of the action is in the first generation or so. In retrospect this seems so obvious that it is hardly worth saying but it wasn’t so obvious to me when I started toying with it.

这模型让我吃惊的地方在于阶级转化为世袭种姓的速度之快:大部分转变在第一代左右就已发生。回想起来,这过程看起来如此明显以致于都不值得谈论,但是一开始我很随意地思考时,我并没有注意到这点。

Even though everything here is selectively neutral, I wonder about the extent to which this free meritocracy mimics selection. Any mutant that boosts merit in carriers will be concentrated in the upper class and vice versa. Greg and I discuss in our book how environmental change initially selects for dinged genes that are “quick fixes” in carriers but detrimental in homozygotes, citing sickle cell in humans, broken myostatin in beef cattle, and numerous others. Does this social system mimic selection?

即使这里的每件事情都是有选择地设为中性,我很想知道这个自由的精英制度与选拔制相似到什么程度。任何让携带者具有个体优势的基因突变都会聚集在较高阶级,反之亦然。Greg和我在我们的书【编注:Greg是Gregory Cochran,作者与他合著了《万年大爆炸》一书,West Hunter是这两位作者的合作博客】中讨论环境改变最初如何选择出了那些丧钟般的“临时补丁”基因,他们能为携带者快速解决一些问题,但对纯合子有害,造成人体内的镰状细胞,菜牛内残缺的肌肉生长抑制素,和很多其他坏处。这个社会系统也模仿选择机制吗?

A correlate of IQ in humans is myopia, one idea being that IQ boosters relax early developmental constraints on CNS growth resulting in eyeballs too big for the socket, leading to myopia. I have read somewhere that myopia is positively related to income in the US. Time to try to find that literature.

跟人类IQ相关的是近视,一种观点认为IQ超群者放松了对中枢神经系统生长的早期发展限制,导致了眼球相比于眼窝过大,于是成了近视。我在某处读到,近视在美国跟收入是正相关的。该去试着找到那篇文献去了。

(编辑:辉格@whigzhou)

*注:本译文未经原作者授权,本站对原文不持有也不主张任何权利,如果你恰好对原文拥有权益并希望我们移除相关内容,请私信联系,我们会立即作出响应。

Class mobility after the first generation is 30% while after four generations it has declined to 10% and continues to decline after that. The average merit in the two classes is about -1SD in the lower and +1SD in the upper on the original scale, corresponding to IQs of 85 and 115.

第一代之后的阶级流动性是30%,而四代之后这个数字就已跌至10%并且之后继续下降。相较于原始水平,较低阶级的平均个体优势降低了一个标准差,较高阶级的平均个体优势增加了一个标准差, 对应的IQ数值为较低阶级的85和较高阶级的115。

Recall that there are no fitness differences in this model. Still, after four generations, about 70% of the variance is between classes, which can be compared to about 35% of the variance among continental human groups for random genetic markers, i.e. colloquially class differences are twice neutral race differences. (The familiar among-population figure of 15% made famous by Lewontin refers to gene differences while here we are comparing genotype differences of diploids, hence the difference between 15 and 35.)

回想下这模型中是没有健康水平的差异的。但在四代之后,阶级之间的方差仍到达了70%,这都可以与随机遗传标记的跨大陆种群间35%的方差相比了,例如,通俗语境中的阶级差异是纯粹种族差异的两倍。(Lewontin提出的著名的种群间15%的差异数据是指基因差异,而这里我们是比较二倍体的基因型差异,因此差别在15到35之间。)

A surprise to me from this model was the rapidity with which classes turn into castes: most of the action is in the first generation or so. In retrospect this seems so obvious that it is hardly worth saying but it wasn’t so obvious to me when I started toying with it.

这模型让我吃惊的地方在于阶级转化为世袭种姓的速度之快:大部分转变在第一代左右就已发生。回想起来,这过程看起来如此明显以致于都不值得谈论,但是一开始我很随意地思考时,我并没有注意到这点。

Even though everything here is selectively neutral, I wonder about the extent to which this free meritocracy mimics selection. Any mutant that boosts merit in carriers will be concentrated in the upper class and vice versa. Greg and I discuss in our book how environmental change initially selects for dinged genes that are “quick fixes” in carriers but detrimental in homozygotes, citing sickle cell in humans, broken myostatin in beef cattle, and numerous others. Does this social system mimic selection?

即使这里的每件事情都是有选择地设为中性,我很想知道这个自由的精英制度与选拔制相似到什么程度。任何让携带者具有个体优势的基因突变都会聚集在较高阶级,反之亦然。Greg和我在我们的书【编注:Greg是Gregory Cochran,作者与他合著了《万年大爆炸》一书,West Hunter是这两位作者的合作博客】中讨论环境改变最初如何选择出了那些丧钟般的“临时补丁”基因,他们能为携带者快速解决一些问题,但对纯合子有害,造成人体内的镰状细胞,菜牛内残缺的肌肉生长抑制素,和很多其他坏处。这个社会系统也模仿选择机制吗?

A correlate of IQ in humans is myopia, one idea being that IQ boosters relax early developmental constraints on CNS growth resulting in eyeballs too big for the socket, leading to myopia. I have read somewhere that myopia is positively related to income in the US. Time to try to find that literature.

跟人类IQ相关的是近视,一种观点认为IQ超群者放松了对中枢神经系统生长的早期发展限制,导致了眼球相比于眼窝过大,于是成了近视。我在某处读到,近视在美国跟收入是正相关的。该去试着找到那篇文献去了。

(编辑:辉格@whigzhou)

*注:本译文未经原作者授权,本站对原文不持有也不主张任何权利,如果你恰好对原文拥有权益并希望我们移除相关内容,请私信联系,我们会立即作出响应。

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

Entrepreneurship and American education

创业活动与美国教育

作者:Michael Q. McShane @ 2016-05-10

译者:Tankman

校对:混乱阈值(@混乱阈值)

来源:AEI,http://www.aei.org/publication/entrepreneurship-and-american-education/

Key Points

要点

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

A Case against Child Labor Prohibitions

对禁用童工的一个反对意见

作者:Benjamin Powell @ 2014-07-29

译者:Eartha(@王小贰_Eartha)

校对:辉格(@whigzhou)

来源:Cato Institute,http://www.cato.org/publications/economic-development-bulletin/case-against-child-labor-prohibitions

Halima is an 11-year-old girl who clips loose threads off of Hanes underwear in a Bangladeshi factory.1 She works about eight hours a day, six days per week. She has to process 150 pairs of underwear an hour. At work she feels “very tired and exhausted,” and sometimes falls asleep standing up. She makes 53 cents a day for her efforts. Make no mistake, it is a rough life.

哈丽玛是个十一岁的小女孩,在孟加拉的工厂里给Hanes牌内衣修线头,每天工作八小时,每周六天。① 她每小时需要处理150套内衣,工作时觉得“非常劳累”,有时站着就睡着了。而这样的努力工作每天能换来53美分。毫无疑问,这种生活非常艰苦。

Any decent person’s heart would go out to Halima and other child employees like her. Unfortunately, all too often, people’s emotional reaction lead them to advocate policies that will harm the very children they intend to help. Provisions against child labor are part of the International Labor Organization’s core labor standards. Anti-sweatshop groups almost universally condemn child labor and call for laws prohibiting child employment or boycotting products made with child labor.

任何一个正派人的内心都会对像哈丽玛这样的童工充满同情。但遗憾的是,人们的情绪化反应常常指引他们支持错误的政策,这反而会伤害那些他们原本想帮助的孩子。禁用童工条款是国际劳工组织的核心劳工标准的一部分。反对血汗工厂的团体几乎一致谴责使用童工的行为,呼吁通过禁止雇佣童工的法律或是抵制使用童工生产的商品。

In my recent book, Out of Poverty: Sweatshops in the Global Economy, I argue that much of what the anti-sweatshop movement agitates for would harm workers and that the process of economic development, in which sweatshops play an important role, is the best way to raise wages and improve working conditions. Child labor, although the most emotionally charged aspect of sweatshops, is not an exception to this analysis.

在我的新书《走出贫困:全球经济中的血汗工厂》中,我认为反血汗工厂运动的许多诉求将会损害工人们的利益,经济发展才是提高工资与改善工作环境的最好办法,而血汗工厂在其中发挥着重要作用。虽然在情感上,雇佣童工是血汗工厂最受世人谴责的方面,但它在上述分析中也不例外。

We should desire to see an end to child labor, but it has to come through a process that generates better opportunities for the children—not from legislative mandates that prevent children and their familie(more...)

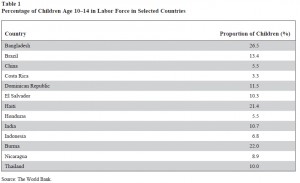

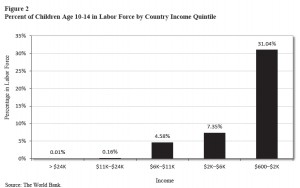

The World Bank also collects data on the economic sectors in which children are employed. Figure 1 presents the distribution of employment of economically active children between the ages of 7 and 14 by sector.6

世界银行也从雇佣童工的各个经济部门收集数据。表一依照经济部门展示了7-14岁年龄段中参与经济活动的儿童在各行业中的分布情况。⑥

The World Bank also collects data on the economic sectors in which children are employed. Figure 1 presents the distribution of employment of economically active children between the ages of 7 and 14 by sector.6

世界银行也从雇佣童工的各个经济部门收集数据。表一依照经济部门展示了7-14岁年龄段中参与经济活动的儿童在各行业中的分布情况。⑥

In seven of the nine countries for which data exists, most children were employed in agriculture, often by a wide margin.7 In the two exceptions, Costa Rica and the Dominican Republic, the leading sector employing children was service. India had the highest proportion of children employed in manufacturing, and there it was a little over 14 percent.

有数据可查的九个国家中,七个国家的大部分儿童受雇于农业部门,远超其他行业。⑦ 哥斯达黎加与多米尼加共和国是两个例外,雇佣童工最多的是服务业。印度制造业雇佣童工的比例在各国中最高,略超过14%。

Protests against sweatshops that use child labor implicitly assume that ending child labor in sweatshops by taking away the option to work in a factory will, on net, reduce child labor. Evidence on child labor in countries that have sweatshops indicates that is wrong. It is not a few “bad apple” firms exploiting children in factories. Child labor is common. Employment in agriculture is not necessarily safer, either. A 1997 child labor survey showed that 12 percent of children working in agriculture reported injuries, compared with 9 percent of those who worked in manufacturing.8

对雇佣童工的血汗工厂进行抗议,这种行为暗含了一种预设,即通过除去儿童在工厂工作的选择从而终结血汗工厂里的童工现象,童工数量就会出现净减少。从拥有血汗工厂的国家所获取的证据显示,这是错的。真相并不是个别“害群之马”在工厂里剥削儿童。雇佣童工的现象是普遍的。而且,在农地里工作也并不必然更加安全。一份1997年的童工调查显示,农业部门有12%的童工曾遭伤害,制造业则是9%。⑧

Child Labor and Economic Development

童工与经济发展

The thought of Third World children toiling in factories to produce garments for us in the developed world to wear is appalling, at least in part because child labor is virtually nonexistent in the United States and the rest of the more developed world.9 Virtually nowhere in the developed world do kids toil long hours every week in a factory in a manner that prevents them from obtaining schooling.

第三世界的儿童们在工厂里辛苦劳动,为我们这些发达地区的人生产服装——这种念头让人惊骇,至少部分原因在于童工事实上并不存在于美国及其他发达地区。⑨ 事实上,没有发达国家会允许儿童们每周长时间地在工厂里辛苦工作,以至于无法接受学校教育。

Children typically worked throughout human history, either long hours in agriculture or in factories once the industrial revolution emerged. The question is, why don’t kids work today? Rich countries do have laws against child labor, but so do many poor countries. In Costa Rica the legal working age is 15, but an ILO survey found 43 percent of working children were under the legal age.10

纵观人类历史,儿童其实一直都在工作,不管是长时间在农地里劳作,还是工业革命之后进入工厂工作。真正该问的问题是:为何今天儿童不工作了?富裕国家确实有禁止童工的法律,但是很多贫穷的国家也有。哥斯达黎加的法定工作年龄是15岁,但是国际劳工组织的一项调查发现有43%的童工低于法定年龄。⑩

Similarly, in the United States, Massachusetts passed the first restriction on child labor in 1842. However, that law and other states’ laws affected child labor nationally very little.11 By one estimate, more than 25 percent of males between the ages of 10 and 15 participated in the labor force in 1900.12 Another study of both boys and girls in that age group estimated that more than 18 percent of them were employed in 1900.13 Economist Carolyn Moehling also found little evidence that minimum-age laws for manufacturing implemented between 1880 and 1910 contributed to the decline in child labor.14

同样,在美国,马萨诸塞州在1842年最先对童工加以限制。然而,那部法律连同其他州的法律对于全国范围内的童工情况影响甚微。⑾ 有人估算过,1900年10-15岁的男性中超过25%的人参与工作.⑿ 另一项研究将同年龄段的女性也纳入了估算范围,结果发现1900年有超过18%的儿童参与了工作。⒀ 经济学家卡洛琳·莫和林也找不到证据证明1880至1910年间针对制造业实施的最低工资法起到了减少童工的作用。⒁

Similarly, economists Claudia Goldin and Larry Katz examined the period between 1910 and 1939 and found that child labor laws and compulsory school-attendance laws could explain at most 5 percent of the increase in high school enrollment.15 The United States did not enact a national law limiting child labor until the Fair Labor Standards Act was passed in 1938. By that time, the U.S. average per capita income was more than $10,200 (in 2010 dollars).

经济学家克劳迪亚·戈尔丁与拉里·卡茨仔细调查了1910至1939年间的情况,发现童工相关的法律与强制入学的法律最多只能解释5%的高中入学率增长幅度。⒂ 直到1938年《公平劳动标准法》通过,美国才有了全国性的限制童工的法律。在那时,美国人均收入已超过10,200美元(以2010年美元计算)。

Furthermore, child labor was defined much more narrowly when today’s wealthy countries first prohibited it. Massachusetts’s law limited children who were under 12 years old to no more than 10 hours of work per day. Belgium (1886) and France (1847) prohibited only children under the age of 12 from working. Germany (1891) set the minimum working age at 13.16

此外,如今的富裕国家当年第一次出台法律禁止童工时,其定义要比现在狭窄的多。马萨诸塞州法禁止12岁以下儿童每天工作超过10小时。比利时(1886年)与法国(1847年)只禁止12岁以下儿童工作。德国(1891年)将最低工作年龄限定在13岁。⒃

England, which passed its first enforceable child labor law in 1833, merely set the minimum age for textile work at nine years old. When these countries were developing, they simply did not put in place the type of restrictions on child labor that activists demand for Third World countries today. Binding legal restrictions came only after child labor had mostly disappeared.

英格兰在1833年通过了第一部童工法,将纺织业的最低工作年龄仅仅设在9岁。当这些国家处于发展阶段,他们通过的限制标准可比不上今天这些活动家对第三世界国家所要求的。有效的法律约束只有在童工几近消失之后才会到来。

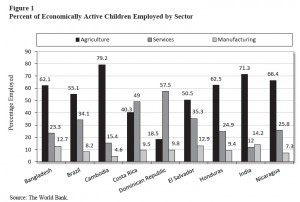

The main reason children do not work in wealthy countries is precisely because they are wealthy. The relationship between child labor and income is striking. Using the same World Bank data on child labor participation rates we can observe how child labor varies with per capita income. Figure 2 divides countries into five groups based on their level of per capita income adjusted for purchasing power parity. In the richest two fifths of countries, all of whose incomes exceed $12,000 in 2010 dollars, child labor is virtually nonexistent.

富裕国家的儿童不工作的主要原因就是他们比较富有。童工比例与收入之间的相关性是显著的。通过前文提到的世界银行关于童工比例的数据,我们可以观察到童工比例是如何随人均收入的变化而改变的。经购买力平价调整后,图2按照人均收入水平将各国分成五组。最富有的两组国家人均收入超过12,000美元(以2010年美元计算),童工几乎不存在。

In seven of the nine countries for which data exists, most children were employed in agriculture, often by a wide margin.7 In the two exceptions, Costa Rica and the Dominican Republic, the leading sector employing children was service. India had the highest proportion of children employed in manufacturing, and there it was a little over 14 percent.

有数据可查的九个国家中,七个国家的大部分儿童受雇于农业部门,远超其他行业。⑦ 哥斯达黎加与多米尼加共和国是两个例外,雇佣童工最多的是服务业。印度制造业雇佣童工的比例在各国中最高,略超过14%。

Protests against sweatshops that use child labor implicitly assume that ending child labor in sweatshops by taking away the option to work in a factory will, on net, reduce child labor. Evidence on child labor in countries that have sweatshops indicates that is wrong. It is not a few “bad apple” firms exploiting children in factories. Child labor is common. Employment in agriculture is not necessarily safer, either. A 1997 child labor survey showed that 12 percent of children working in agriculture reported injuries, compared with 9 percent of those who worked in manufacturing.8

对雇佣童工的血汗工厂进行抗议,这种行为暗含了一种预设,即通过除去儿童在工厂工作的选择从而终结血汗工厂里的童工现象,童工数量就会出现净减少。从拥有血汗工厂的国家所获取的证据显示,这是错的。真相并不是个别“害群之马”在工厂里剥削儿童。雇佣童工的现象是普遍的。而且,在农地里工作也并不必然更加安全。一份1997年的童工调查显示,农业部门有12%的童工曾遭伤害,制造业则是9%。⑧

Child Labor and Economic Development

童工与经济发展

The thought of Third World children toiling in factories to produce garments for us in the developed world to wear is appalling, at least in part because child labor is virtually nonexistent in the United States and the rest of the more developed world.9 Virtually nowhere in the developed world do kids toil long hours every week in a factory in a manner that prevents them from obtaining schooling.

第三世界的儿童们在工厂里辛苦劳动,为我们这些发达地区的人生产服装——这种念头让人惊骇,至少部分原因在于童工事实上并不存在于美国及其他发达地区。⑨ 事实上,没有发达国家会允许儿童们每周长时间地在工厂里辛苦工作,以至于无法接受学校教育。

Children typically worked throughout human history, either long hours in agriculture or in factories once the industrial revolution emerged. The question is, why don’t kids work today? Rich countries do have laws against child labor, but so do many poor countries. In Costa Rica the legal working age is 15, but an ILO survey found 43 percent of working children were under the legal age.10

纵观人类历史,儿童其实一直都在工作,不管是长时间在农地里劳作,还是工业革命之后进入工厂工作。真正该问的问题是:为何今天儿童不工作了?富裕国家确实有禁止童工的法律,但是很多贫穷的国家也有。哥斯达黎加的法定工作年龄是15岁,但是国际劳工组织的一项调查发现有43%的童工低于法定年龄。⑩

Similarly, in the United States, Massachusetts passed the first restriction on child labor in 1842. However, that law and other states’ laws affected child labor nationally very little.11 By one estimate, more than 25 percent of males between the ages of 10 and 15 participated in the labor force in 1900.12 Another study of both boys and girls in that age group estimated that more than 18 percent of them were employed in 1900.13 Economist Carolyn Moehling also found little evidence that minimum-age laws for manufacturing implemented between 1880 and 1910 contributed to the decline in child labor.14

同样,在美国,马萨诸塞州在1842年最先对童工加以限制。然而,那部法律连同其他州的法律对于全国范围内的童工情况影响甚微。⑾ 有人估算过,1900年10-15岁的男性中超过25%的人参与工作.⑿ 另一项研究将同年龄段的女性也纳入了估算范围,结果发现1900年有超过18%的儿童参与了工作。⒀ 经济学家卡洛琳·莫和林也找不到证据证明1880至1910年间针对制造业实施的最低工资法起到了减少童工的作用。⒁

Similarly, economists Claudia Goldin and Larry Katz examined the period between 1910 and 1939 and found that child labor laws and compulsory school-attendance laws could explain at most 5 percent of the increase in high school enrollment.15 The United States did not enact a national law limiting child labor until the Fair Labor Standards Act was passed in 1938. By that time, the U.S. average per capita income was more than $10,200 (in 2010 dollars).

经济学家克劳迪亚·戈尔丁与拉里·卡茨仔细调查了1910至1939年间的情况,发现童工相关的法律与强制入学的法律最多只能解释5%的高中入学率增长幅度。⒂ 直到1938年《公平劳动标准法》通过,美国才有了全国性的限制童工的法律。在那时,美国人均收入已超过10,200美元(以2010年美元计算)。

Furthermore, child labor was defined much more narrowly when today’s wealthy countries first prohibited it. Massachusetts’s law limited children who were under 12 years old to no more than 10 hours of work per day. Belgium (1886) and France (1847) prohibited only children under the age of 12 from working. Germany (1891) set the minimum working age at 13.16

此外,如今的富裕国家当年第一次出台法律禁止童工时,其定义要比现在狭窄的多。马萨诸塞州法禁止12岁以下儿童每天工作超过10小时。比利时(1886年)与法国(1847年)只禁止12岁以下儿童工作。德国(1891年)将最低工作年龄限定在13岁。⒃

England, which passed its first enforceable child labor law in 1833, merely set the minimum age for textile work at nine years old. When these countries were developing, they simply did not put in place the type of restrictions on child labor that activists demand for Third World countries today. Binding legal restrictions came only after child labor had mostly disappeared.

英格兰在1833年通过了第一部童工法,将纺织业的最低工作年龄仅仅设在9岁。当这些国家处于发展阶段,他们通过的限制标准可比不上今天这些活动家对第三世界国家所要求的。有效的法律约束只有在童工几近消失之后才会到来。

The main reason children do not work in wealthy countries is precisely because they are wealthy. The relationship between child labor and income is striking. Using the same World Bank data on child labor participation rates we can observe how child labor varies with per capita income. Figure 2 divides countries into five groups based on their level of per capita income adjusted for purchasing power parity. In the richest two fifths of countries, all of whose incomes exceed $12,000 in 2010 dollars, child labor is virtually nonexistent.

富裕国家的儿童不工作的主要原因就是他们比较富有。童工比例与收入之间的相关性是显著的。通过前文提到的世界银行关于童工比例的数据,我们可以观察到童工比例是如何随人均收入的变化而改变的。经购买力平价调整后,图2按照人均收入水平将各国分成五组。最富有的两组国家人均收入超过12,000美元(以2010年美元计算),童工几乎不存在。

It is only when countries have an income less than $11,000 per year that we start to observe children in the labor force. But even here, rates of child labor remain relatively low through both the third and fourth quintiles. It is the poorest countries where rates of child labor explode. More than 30 percent of children work in the fifth of countries with incomes ranging from $600 to $2,000 per year. Economists Eric Edmonds and Nina Pavcnik econometrically estimate that 73 percent of the variation of child labor rates can be explained by variation in GDP per capita.17

只有当一个国家的人均年收入低于11,000美元时,我们才开始观察到童工。即便如此,在第三与第四组国家中,中等及中等偏上收入家庭的童工比例相对来说也很低。而在穷国,童工比例暴增。最为贫穷的那组国家中,人均年收入在600美元到2,000美元之间,童工比例超过了30%。经济学家Eric Edmonds 与 Nina Pavcnik 运用计量经济学测算,认为童工比例差异中的73%可由人均GDP差异来解释。⒄

Of course, correlation is not causation. But in the case of child labor and wealth, the most intuitive interpretation is that increased wealth leads to reduced child labor. After all, all countries were once poor; in the countries that became rich, child labor disappeared. Few would contend that child labor disappeared in the United States or Great Britain prior to economic growth taking place—children populated their factories much as they do in the Third World today.

当然,有相关性不代表存在因果关系。但是当我们思考童工与财富之间的关系时,最符合直觉的解读就是财富的增长减少了童工。毕竟,所有国家都有过贫穷的阶段;在那些富裕起来的国家里,童工就消失了。鲜有人认为美国或者英国的童工在经济发展之前就已经消失了——就像今日的第三世界,工厂里到处都是儿童。

A little introspection, or for that matter our moral indignation at Third World child labor, reveals that most of us desire that children, especially our own, do not work. Thus, as we become richer and can afford to allow children to have leisure and education, we choose to.

我们对历史所做的一些反省,抑或出于对第三世界童工现象的道德愤慨,这些其实都反映了我们中的大部分人不希望孩子们去工作,尤其是自己的孩子。因此,当我们变得有钱,能够为孩子们提供闲暇的生活与教育之时,我们就这样做了。

Conclusion

结论

The thought of children laboring in sweatshops is repulsive. But that does not mean we can simply think with our hearts and not our heads. Families who send their children to work in sweatshops do so because they are poor and it is the best available alternative open to them. The vast majority of children employed in countries with sweatshops work in lower-productivity sectors than manufacturing.

让儿童在血汗工厂里工作的想法令人厌恶,但这不意味着我们就该简单地让同情心泛滥,而舍弃大脑的思考。家长把孩子送去血汗工厂里工作,是因为他们太穷了,而这已是可选的选项中最好的选择。在有着血汗工厂的国家里,大多数童工所在行业的生产能力比制造业更低。

Passing trade sanctions or other laws that take away the option of children working in sweatshops only limits their options further and throws them into worse alternatives. Luckily, as families escape poverty, child labor declines. As countries become rich, child labor virtually disappears. The answer for how to cure child labor lies in the process of economic growth—a process in which sweatshops play an important role.

出台贸易制裁措施或其他法律,将这些儿童的工作机会夺走,这只会进一步限制他们的选择,陷他们于更糟糕的境地之中。值得庆幸的是,当这些家庭脱离贫困之后,童工就减少了。随着国家慢慢富裕起来,童工在事实上就会消失。如何解决童工问题的答案就在经济发展的过程之中,而血汗工厂则在其中扮演了重要角色。

Notes

注记

It is only when countries have an income less than $11,000 per year that we start to observe children in the labor force. But even here, rates of child labor remain relatively low through both the third and fourth quintiles. It is the poorest countries where rates of child labor explode. More than 30 percent of children work in the fifth of countries with incomes ranging from $600 to $2,000 per year. Economists Eric Edmonds and Nina Pavcnik econometrically estimate that 73 percent of the variation of child labor rates can be explained by variation in GDP per capita.17

只有当一个国家的人均年收入低于11,000美元时,我们才开始观察到童工。即便如此,在第三与第四组国家中,中等及中等偏上收入家庭的童工比例相对来说也很低。而在穷国,童工比例暴增。最为贫穷的那组国家中,人均年收入在600美元到2,000美元之间,童工比例超过了30%。经济学家Eric Edmonds 与 Nina Pavcnik 运用计量经济学测算,认为童工比例差异中的73%可由人均GDP差异来解释。⒄

Of course, correlation is not causation. But in the case of child labor and wealth, the most intuitive interpretation is that increased wealth leads to reduced child labor. After all, all countries were once poor; in the countries that became rich, child labor disappeared. Few would contend that child labor disappeared in the United States or Great Britain prior to economic growth taking place—children populated their factories much as they do in the Third World today.

当然,有相关性不代表存在因果关系。但是当我们思考童工与财富之间的关系时,最符合直觉的解读就是财富的增长减少了童工。毕竟,所有国家都有过贫穷的阶段;在那些富裕起来的国家里,童工就消失了。鲜有人认为美国或者英国的童工在经济发展之前就已经消失了——就像今日的第三世界,工厂里到处都是儿童。

A little introspection, or for that matter our moral indignation at Third World child labor, reveals that most of us desire that children, especially our own, do not work. Thus, as we become richer and can afford to allow children to have leisure and education, we choose to.

我们对历史所做的一些反省,抑或出于对第三世界童工现象的道德愤慨,这些其实都反映了我们中的大部分人不希望孩子们去工作,尤其是自己的孩子。因此,当我们变得有钱,能够为孩子们提供闲暇的生活与教育之时,我们就这样做了。

Conclusion

结论

The thought of children laboring in sweatshops is repulsive. But that does not mean we can simply think with our hearts and not our heads. Families who send their children to work in sweatshops do so because they are poor and it is the best available alternative open to them. The vast majority of children employed in countries with sweatshops work in lower-productivity sectors than manufacturing.

让儿童在血汗工厂里工作的想法令人厌恶,但这不意味着我们就该简单地让同情心泛滥,而舍弃大脑的思考。家长把孩子送去血汗工厂里工作,是因为他们太穷了,而这已是可选的选项中最好的选择。在有着血汗工厂的国家里,大多数童工所在行业的生产能力比制造业更低。

Passing trade sanctions or other laws that take away the option of children working in sweatshops only limits their options further and throws them into worse alternatives. Luckily, as families escape poverty, child labor declines. As countries become rich, child labor virtually disappears. The answer for how to cure child labor lies in the process of economic growth—a process in which sweatshops play an important role.

出台贸易制裁措施或其他法律,将这些儿童的工作机会夺走,这只会进一步限制他们的选择,陷他们于更糟糕的境地之中。值得庆幸的是,当这些家庭脱离贫困之后,童工就减少了。随着国家慢慢富裕起来,童工在事实上就会消失。如何解决童工问题的答案就在经济发展的过程之中,而血汗工厂则在其中扮演了重要角色。

Notes

注记

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

Aid and Politics

援助与政治

作者:Angus Deaton @ 2013-08-16

译者:沈沉(@你在何地-sxy)

校对:辉格(@whigzhou)

来源:Princeton University Press,http://press.princeton.edu/chapters/s2_10054.pdf

To understand how aid works we need to study the relationship between aid and politics. Political and legal institutions play a central role in setting the environment that can nurture prosperity and economic growth. Foreign aid, especially when there is a lot of it, affects how institutions function and how they change. Politics has often choked off economic growth, and even in the world before aid, there were good and bad political systems.

要理解援助是如何运作的,我们需要对援助与政治之间的关系做一番研究。在创造恰当环境以促进繁荣和经济增长方面,政治和法律制度扮演着关键的角色。外国援助,特别是大额外国援助,会影响制度的运作及其变迁。政治向来能阻碍经济增长,即便是在援助流行以前,世上也既有好的政治体系,也有坏的。

But large inflows of foreign aid change local politics for the worse and undercut the institutions needed to foster long-run growth. Aid also undermines democracy and civic participation, a direct loss over and above the losses that come from undermining economic development. These harms of aid need to be balanced against the good(more...)

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

【2017-02-15】

Flynn事件的最佳结果是:除掉川普团队中的几条川普狗,让共和党主流塞进更多人,最终让川普专注于上镜头过戏瘾和给白左做脱敏治疗,把大事交给其他人……好像也不是完全不可能。

【2017-02-14】

这两份书单的质量非常高,其中不少是我打过五星的,估计其余的也不错,打算通读:

The 25 most stimulating economic history books since 2000

Big History and “Deep Determinants” (published since 2000)

‘We Hillbillies Have Got to Wake the Hell Up': Review of Hillbilly Elegy

“我们这些山巴佬该醒醒了”——《山乡挽歌》书评

A family chronicle of the crackup of poor working-class white Americans.

一份贫穷糟糕美国白人工薪阶层的家庭编年史

作者:Ronald Bailey @ 2016-07-29

翻译:Drunkplane(@Drunkplane-zny)

校对:babyface_claire

来源:reason.com,http://reason.com/archives/2016/07/29/we-hillbillies-have-got-to-wake-the-hell

【编注:hillbilly和redneck、yankee、cracker一样,都是对美国某个有着鲜明文化特征的地方群体的蔑称,本文译作『山巴佬』】

Read this remarkable book: It is by turns tender and funny, bleak and depressing, and thanks to Mamaw, always wildly, wildly profane. An elegy is a lament for the dead, and with Hillbilly Elegy Vance mourns the demise of the mostly Scots-Irish working class from which he springs. I teared up more than once as I read this beautiful and painful memoir of his hillbilly family and their struggles to cope with the modern world.

阅读这本非凡之作的感受时而温柔有趣,时而沮丧压抑,而且,亏了他的祖母,还往往十分狂野,狂野地对神不敬。挽歌是对死人的悼念。Vance用《山乡挽歌》缅怀了苏格兰-爱尔兰裔工人阶级的衰亡,他自己便出身于此阶级。这本书描写了他的乡下家庭及其在现代社会中的挣扎,在阅读这本美丽而痛苦的回忆录时,我几度流泪。

Vance grew up poor with a semi-employed, drug-addicted mother who lived with a string of five or six husbands/boyfrie(more...)

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——

Why are we so afraid to leave children alone?

为什么我们害怕让孩子独处?

作者:Pat Harriman & Heather Ashbach, UC Irvine @ 2016-08-23

译者:明珠(@老茄爱天一爱亨亨更爱楚楚)

校对:babyface_claire(@许你疯不许你傻)

来源:UC, http://universityofcalifornia.edu/news/why-are-we-so-afraid-leave-children-alone

Leaving a child unattended is considered taboo in today’s intensive parenting atmosphere, despite evidence that American children are safer than ever. So why are parents denying their children the same freedom and independence that they themselves enjoyed as children?

在今天这种强化父母责任的社会氛围中,留下孩子无人照看被视为禁忌,虽然有证据表明美国孩子比以往任何时候都更安全。那么,为什么父母拒绝孩子拥有从前他们自己是孩子时享受的同样的自由和独立呢?

A new study by University of Calif(more...)

——海德沙龙·翻译组,致力于将英文世界的好文章搬进中文世界——